Frank Stella at LACMA, 1964

Clement Greenberg made his name as the critic who most articulately championed New York-based Abstract Expressionism as the most convincing and historically relevant artform of the mid-Twentieth Century. But by the early 60s he had become disillusioned, finding most of the art being made in this style to be mannered imitations. Sensing it was time for change, in 1964 he organized an exhibition at LACMA called “Post-Painterly Abstraction” to argue for a new generation of painters who favored a cool, flat surface, often stained or poured rather than visibly brushed and agitated. There were 31 artists in the show, including Helen Frankenthaler, Sam Gilliam, Al Held, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Frank Stella.

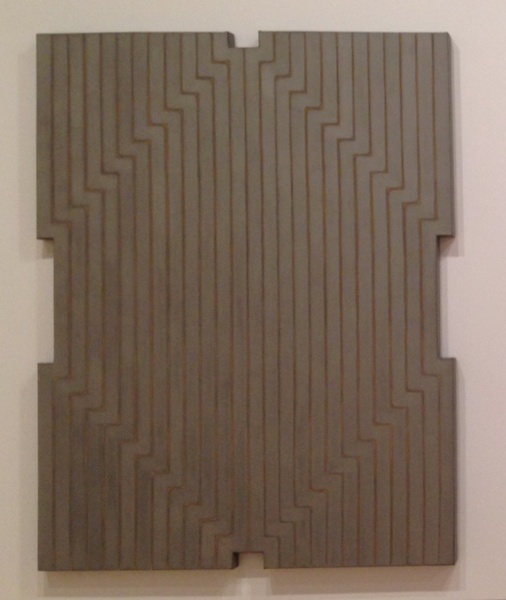

In many ways Stella was the seminal figure in the group, although the severity of his first paintings, from 1959, left many thinking he had played a kind of endgame, leaving painting no way forward. These were the so-called “Black Paintings,” made by applying black enamel paint in evenly measured stripes on bare, unprepared canvas. In a radio broadcast the same year as the Los Angeles show he said, “My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object… All I want anyone to get out of my paintings, and all I ever get out of them, is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion…. What you see is what you see.”

The paintings included in the LACMA show were from 1960, made on notched canvases with aluminum paint. One of the works, “Marquis de Portago,” from the collection of local collectors, Donald and Lynn Factor, was damaged when someone walked on it during installation. Stella was asked about the feasibility of restoring it, but once it was returned to his studio, he considered it irreparable. Instead, he painted the Factors a new version. But a year later Stella did repair the damaged canvas and sold it to the Massachusetts collectors Ann and Graham Gund. In 1970 the Factors brought their painting to auction at Parke-Bernet, and only then discovered what had happened, and that their painting, as a copy, was worth half of what they had expected. They sued Stella, and he was found negligent for not keeping them informed, but no damages were assessed.