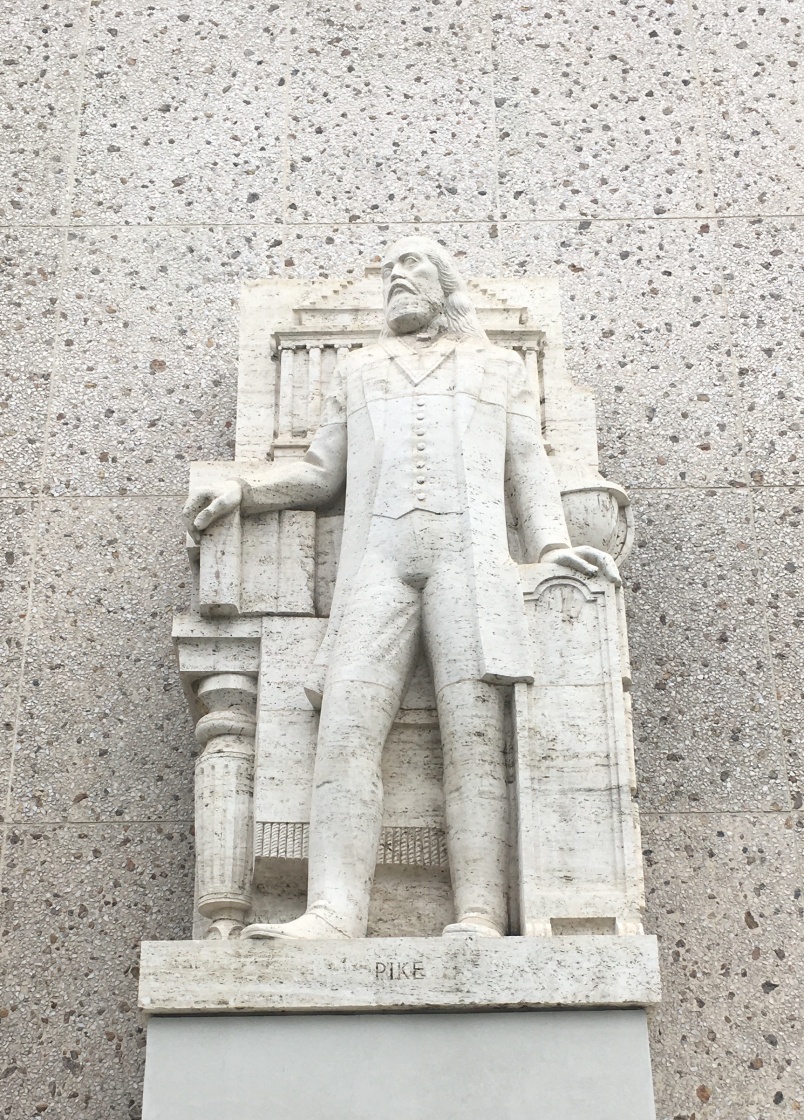

Millard Sheets, Albert Stewart: Monument to Freemason, Albert Pike, Scottish Rite Temple, 1961

On July 22 The New York Times reported that the Marciano Art Foundation settled a lawsuit charging that the foundation broke the law by laying off 70 part-time employees who had announced plans to unionize. Under the terms of the agreement, the former workers will receive about 10 weeks of pay, and some help with legal fees. The union — District Council 36 of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees — has now dropped a charge of unfair labor practices filed with the National Labor Relations Board.

Although the Marciano Foundation is closed to the public, the collection is still housed in the monumental former Scottish Rite Temple on Wilshire Boulevard. This enigmatic building presents a windowless wall of white travertine to the street, decorated with some uplifting text and masonic signage above the recessed entrance and a row of giant figures representing significant individuals, both historical and mythic, in the history of Freemasonry. It was completed in 1961, to the designs of the polymath artist/designer/educator, Millard Sheets, who is perhaps best known for his work designing buildings and mosaics for the Home Savings and Loan Bank throughout the west. He was an outspoken proponent of an idea of art as a kind of civic activity; a group of craftsmen working under the guidance of a master, in what he believed to be the model of the Italian Renaissance, to create an uplifting representation of a common history. (A quick look at any of the surviving banks — at Sunset and Vine, Wilshire and 26th Street in Santa Monica, for instance — will show that version of history to be a triumphalist, colonialist view.)

The temple was commissioned when Freemasonry was on the ascendant in Los Angeles, but within 30 years membership had plummeted, and to keep up expenses the Masons tried renting out the space for events and functions. A few punk concerts soured the neighborhood, and the only reliable customers proved to be the LAPD, who used the space for funerals and SWAT team exercises. During the 1992 uprising, it was used as a temporary barracks by the National Guard. After that the building was put up for sale and lay empty and unused for years. The Marciano brothers bought it in 2013; when they opened their museum in 2017, few people knew much about the interior, but the row of giant figures along the Wilshire façade continued to be an object of, mostly unknowing, fascination. Their stylistic mannerisms had a kitsch appeal, but if you stopped to take a closer look, the inscrutable names carved into the plinths — Imhotep, Hiram, Rheims — likely meant nothing.

Sheets talked about the entire project in a 1976-77 for the UCLA Oral History project, and had this to say about the sculptures:

“…the concept of the sculpture along the south facade, which I worked in collaboration with Albert Stewart to design, and then he made all of the models — it seems to me there were eighty scale models, which I took to Rome and had carved by a very fine sculptor in solid travertine. These were, of course, eventually sent back and placed on the façade. And here again are all of the temple builders, each one representing a special builder going back to ancient Egypt and coming on through the time of King Solomon and the Persian emperor, up to and including George Washington. There are also Albert Pike, who was one of the very great men in the early part of the 20th century or latter part of the 19th century, and Christopher Wren, who built the great cathedrals in England. The two St. Johns were interesting, because they were said to be patron saints, and they depicted two different meanings entirely. Then there’s the Gothic builder, so it symbolizes the whole meaning of the building of the temple.”

Including George Washington? Most people driving on Wilshire would not have noticed him. His likeness is around the corner, on the far side of the building, along with this Albert Pike, “who was one of the very great men in the early part of the twentieth century or latter part of the nineteenth.” How could such a very great person come to be so forgotten?

In the years following the Civil War, Pike — a one-time Confederate general — became the intellectual force behind the development of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite in Washington D.C. Working within the same political milieu that was framing the “Lost Cause” whitewash of the Confederacy, he codified the rituals and identified the ranks members could strive to attain with a set of titles suitable for a romance novel — Secret Master, Knight of the Sword, Knight of the Sun, Master of the Royal Secret, Sovereign Grand Commander. In the late 18th century, when George Washington was a Mason, the organization was of interest to revolutionaries because it was egalitarian, and its members thought deeply about governance structures. Refashioned by Pike and his contemporaries, Masonic Lodges became clubs for the privileged, masking reactionary politics behind secret rituals. And similar fraternities were springing up across the South at that time, most notoriously the Ku Klux Klan. There is some controversy around Pike’s membership of the KKK, but he did write of his desire to see a larger and more centralized secret organization to promote white supremacy. In an editorial for a Memphis-based newspaper, he wrote, “If it were in our power, if it could be effected, we would unite every white man in the South, who is opposed to negro suffrage, into one great Order of Southern Brotherhood, with an organization complete, active, vigorous, in which a few should execute the concentrated will of all, and whose very existence should be concealed from all but its members.”

In a late 2016 preview of the soon to open Marciano Art Foundation, Jamie G. Manné, the founding director, is quoted as saying, “The mystery and allure of the original building factors heavily into the museum’s identity.” She went on to add, “I think people are as excited about the building as the collections. There’s just this great curiosity about it.” It is unclear that anyone within the Marciano universe was aware of the dark stain of racism hiding behind the blank façade of the white monolith. There is now no way to check — the Marciano Art Foundation website is completely blank, a white page.

And Albert Pike? A large-scale bronze memorial was erected in the Judiciary Square neighborhood of Washington, DC in 1901, making him the only Confederate officer publicly commemorated in the nation’s capital. Protesters tore it down on June 19, 2020.