A Tale of Two Art Dealers

by Darcy Tell

Left: Irving Blum, ca. 1962. Photo: Frank J. Thomas. Courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archive. Right: Everett Ellin, ca. 1958-1963. Everett Ellin papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In many instances, what was happening in the East was simply more powerful, more convincing, and more intriguing. —Irving Blum1

In the late fifties, the outlines of the Los Angeles art world were narrow by anybody’s standard. Unlike many regional cities of equivalent wealth, the city still lacked an independent encyclopedic museum. There were no modernist or contemporary art museums, just the lingering, humiliating memory of the short-lived Modern Institute of Art started by Vincent Price and others in 1947. UCLA had muffed the Arensberg-Scheyer donation in 1950.2Contemporary art was mistrusted. The public ignored it, and conservatives—most vocally, government officials and figurative or “Sunday” painters—demonized it.3Even so, an art market existed but just barely.

There were a few elite dealers in town by the late fifties. Frank Perls, a German refugee, opened in 1939. He was from a family of art merchants and established a thoroughly professional gallery that sold 19th- and 20th-century European art as well as contemporary and older work from California and the United States.4Perls energetically supported the local art culture. He lectured, lent and rented art, judged competitions, and raised money. His letters show him to be humorous, opinionated, and, though completely aware of his adopted city’s provincialism, confident that it could—and would—become an important center someday.5

Perls had quite a few colleagues, both immigrant and native-born, who operated in the same way. These men sold what we would now call blue-chip art, contemporary European and American work, regional paintings, and even antiquities.6The secondary market—private, discreet—was a mainstay. These dealers kept track of who owned which valuable paintings, bought and sold, searched for new collectors, and looked after the old ones. This kind of business moved outward from its clients and the painstaking work of following collections and monitoring taste. Even so, it was not that uncommon for galleries in Southern California to show contemporary artists. When they did, however, they usually held shows of established artists, many of them from the East or at least outside LA. With gallery space so scarce and a market predisposed toward artists with reputations, the youngest Southern California artists were marginalized.

About the same time Blum and Hopps were making over Ferus, another easterner established a gallery of contemporary art in Santa Monica. Everett Ellin was born in 1928 in Chicago. When he showed up in California, he had degrees in engineering (University of Michigan) and law (Harvard) and had served during the Korean War. He clerked for a California Supreme Court justice and then worked at Paramount and the William Morris agency. His Los Angeles art project started naturally enough through his girlfriend, the painter Joan Jacobs. She and her friends needed somebody to write contracts, and after he agreed, they urged Ellin to start a gallery. He opened in 1958 in Santa Monica, where he showed Jacobs and several other California artists.12

Ellin took easily to dealing but, apparently knowing something of American art, was immediately drawn to New York. “Dying of curiosity to see the whole Abstract Expressionist environment in action,” he went to the city and made the rounds. In what was, by Ellin’s account, a lucky accident, dealer Sam Kootz told Ellin about a gallery job at French and Company, a blue-chip antiques business founded at the beginning of the century that was opening a contemporary art section. Kootz arranged an interview.13

The eye behind the contemporary program at French and Company was Clement Greenberg, America’s most famous art critic. Clem, as he was known to his friends, needed money badly. However, at a time when the distinction between the commercial and intellectual was deadly serious, to the intellectual at least, he insisted that the gallery have a director to handle the details of selling so that he might maintain “his image as a connoisseur […] visionary .[…] and critic.”14After a quick interview, Ellin got the job.

The gallery, with a roster of New York’s most famous painters and a magnificent skylighted space, was extremely high-powered, as Ellin discovered. “I met all the collectors. I met all the museum people. I met the critics. I just dealt with everybody. Clem didn’t want to do any of that. And I had tremendous exposure because everybody came to David Smith [a retrospective at French and Company]. […] The attendance was unbelievable, and it didn’t stop for the entire run of the show. It was that way every day, and all the directors, all the museum directors, came and I got to meet them.”15 More intangible but just as important, the methodical Ellin was exposed to New York’s gallery world at a very high level of commercial sophistication and intellectual ambition. Unfortunately, luxe decor and prestigious shows could hide the gallery’s shaky finances for only so long, and the contemporary section at French and Company folded in less than a year.16 Ellin decided to open another gallery in Los Angeles. This time, he wanted to set himself apart from the galleries that were beginning to cluster on La Cienega, where Ferus had its new space, and he located on the Sunset Strip instead.

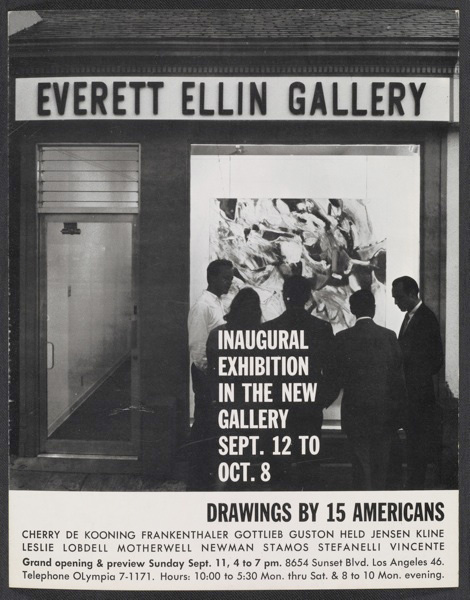

An exhibition announcement for the Everett Ellin Gallery’s inaugural exhibition, 1960. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Predictably, after his stint as Clem Greenberg’s protégé, Ellin created a program that explicitly stood on his “admiration for the New York School.” From September 1962 through December 1963, building on his experience at French and Company and intentionally carrying on his work there, he put on what he called ‘“museum-grade’” shows.17 These ambitious exhibitions included recent, historical, and earlier postwar works of very high—read New York—quality, often borrowed from dealers in the city.

The first was a drawing show that included work by one California artist, Frank Lobdell, among more famous painters from the East. Next, he opened a version of the large David Smith show he’d organized at French and Company, which had gotten great reviews during the New York run.18Smith came out for the opening.19In a Los Angeles Times interview, he talked art, giving readers serious, articulate intellectualizing delivered in classic Ab Ex style. He embraced abstraction, for example, but he told the Times there was room for “images of recognition […] as long as they are masterfully expressed.”20 To Smith, “Conviction,” as the headline read, was “all that counts.”

Ellin followed up the Smith exhibition with an eclectic program that reflected the variety of New York sources he relied on. He showed earlier modernists like Arp and several Dadaists, Helen Frankenthaler, Arshile Gorky, Jack Youngerman, and Jasper Johns. He also showed a few West Coast artists, including Joan Jacobs (by then his wife, who was much encouraged and admired by David Smith).

In March 1962, apparently at the request of dealer Virginia Dwan, Ellin exhibited work by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint-Phalle. As part of this show, Saint-Phalle staged her first American Action de Tir in an alley off the Sunset Strip near Ellin’s gallery, a performance in which she, aided by Tinguely and Kienholz, shot paint at a target 6 meters away. Saint-Phalle’s revolutionary act, which we now recognize as a harbinger of a new art world, at the time drew only short mention in the local press. Nor does it seem to have made much of an impression on Ellin; he never talked about it in later interviews and did not include it in the meticulous chronology he prepared to go with his papers when they were donated to the Smithsonian.21

Niki de Saint-Phalle, Action de tir, 1962. Performed at the Everett Ellin Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Seymour Rosen. Courtesy of the Estate of Seymour Rosen and SPACES, Aptos, CA.

Ellin worked hard to project the sense of artistic conviction he had soaked up during his brief time on Madison Avenue, and his shows reflected the quality and variety of his connections. But whether they focused on Abstract Expressionist or avant-garde artists, Ellin’s elegant, serious shows did not make money. The central problem was that Los Angeles lacked the kind of customers he needed: men and women with some knowledge and, perhaps more important, confidence, whom he could develop as collectors. “I couldn’t really plan to continue doing the kind of shows I was doing. And it was really hard for me to think of having a gallery that did less […] once I set those standards and got into that groove and I could get any material I wanted.

“Everybody from New York thought that they were going to be getting Los Angeles collectors, and, you know, they did. The collectors in Los Angeles would learn from me and buy in New York.”22 He carried on through the end of 1963, when once again he got a great job in New York by accident. This time, he worked briefly for the Marlborough Gallery and its founder, Frank Lloyd.23 Next, he worked for the Guggenheim Museum, and finally, he organized, piloted, and led the Museum Computer Network, the first effort to systematize museum information in database form, the achievement for which Ellin remains most famous.24

For a while there in the early sixties, it looked like a real solid art scene was developing in California. Even Henry Geldzahler [of the Metropolitan Museum] felt he had to make a trip once a year to check on what was happening. But there weren’t enough dealers there and the museums weren’t active enough, and the people just weren’t buying art—they were satisfied looking at the scenery, I guess. —Andy Warhol25

In his 2004 interview, Ellin talked a little about his colleagues in Los Angeles and tried to explain why the art world in Los Angeles fell short. “Paul Kantor […] had a very elegant practice selling high-priced 20th-century pictures,” he said, “and Frank Perls had been around a long time.” However, it seemed to Ellin that “quite a few [LA] galleries […] were just making the motions. […] They didn’t have a particular message. They were doing all right, but there was so little there. We were not producing the collectors because we didn’t have the good stuff in Los Angeles.”26

Ellin’s remark betrays his very specific point of view—that of a non-Angeleno engineer turned art dealer with a JD law degree from Harvard and values that he’d absorbed from his mentor Greenberg, Abstract Expressionist artist friends, and his immersion course in the conventions of Madison Avenue art-world theater. It also nicely sums up the deficiencies of the art world in Los Angeles at this time, as judged by people with experience of the East Coast art world and strong ideas of what constituted a serious art scene. To these men (most of them were men), the Los Angeles art world lacked the necessary ecology in the practical sense. Beyond that, over and over, like Ellin, they offered another, more free-floating criticism: Art culture in Los Angeles lacked the right attitude. Since the 1940s, Clem Greenberg, as he became the dominating presence on the American art scene, argued for the historical inevitability of abstraction and the imperative to advance modernism. Polemical and extremely aggressive—he now can seem like a figure from Cold War central casting, as do many of the artists in his ambit—Greenberg set the terms in which American painting was discussed and sometimes made.27 The sectors that made up the art world in these years must have felt Greenberg’s influence in slightly different ways, but they all felt it. By the late 1950s, for instance, artists all over the country were forcefully aware of Greenberg’s ambitious ideas, perhaps through reading or from exhibitions, teachers, or fellow painters. Imposed with absolute authority, these must have seemed bewilderingly large to many artists as they worked in their studios, but whether you loved or hated them, by the late fifties and into the sixties, even in distant Los Angeles, they were known by all to be art’s orthodoxy. As his friend and protégé David Smith told the Los Angeles Times, conviction was what mattered in your art. During the years that Greenberg championed postwar American painting so effectively, the expectation of intensity and aggressive self-assertion was extended to how artists behave. For dealers and collectors, especially in Los Angeles, the interplay of action and the imaginary was more complex.

To sell art, dealers often depend on—indeed create—a subtle atmosphere of associations. Projecting visually and with words ideas or traditions or tastes, the seller of art evokes a powerful set of images for buyers. This work does not depart fundamentally from what someone selling clothes does: To make a sale, dealers may affirm, charm, cajole, or directly manipulate a customer. With art as with clothes, any number of collective signifiers and individual tendencies can be in play.

As I’ve said, in Los Angeles at this time, everyone interested in contemporary art understood the dominant signifiers that had largely developed in New York. To, as Blum put it, “be considered in a larger way,” artists were expected to express the requisite sense of mission with intensity, self-confidence, and sense of consequence that Greenberg preached. To sell, dealers would as a matter of course project the same kind of associations to convince collectors to buy. For the Blums and Ellins, the intractable problem was that the larger world of Los Angeles—the world with the money—did not yet understand what insiders knew so well.

Compounding the problem in the city was the fact that both Ellin and Blum were operating at a time of major transition in the American art world. Andy Warhol described this new phase as the “late post–Abstract Expressionist days […] right before Pop,” a time in which young artists of many different tendencies were challenging Abstract Expressionism’s domination.28 Warhol gives hilarious descriptions of the surprisingly intense confrontations between older and younger New York in the very early 1960s. His funny and clear observations make you wonder, too, how the shift away from Abstract Expressionism played out in Los Angeles, a city full of imaginative artists and lacking in educated collectors, with the dealers in between.

During their years in the California market, Irving Blum and Everett Ellin each responded in a different way to the considerable problems of selling art in Los Angeles at this moment. The stolid Ellin looked backward and East: Most of the art he showed, borrowed from New York dealers, satisfied Greenbergian standards of artistic inquiry and the aspiration to be taken seriously. To convince and persuade the very few potential buyers, he simply reproduced the practices he’d learned on Madison Avenue. And he failed.

Blum was more flexible and forward-looking. He knew that Ferus needed added credibility to avoid being seen as a provincial gallery. As he put it, “I just didn’t want the stigma. My ambitions were greater than that.”29 So he tacked and trimmed nimbly to reposition the gallery, adapting what Ferus already had, moving to a redesigned white-box space on the street, purging the Beatnik-hipster aesthetic that had been influential at the gallery. Central to his plan of reinvention was to show New York as well as Los Angeles artists.

Interestingly, Blum projected the sense of serious purpose that was expected of a successful art gallery, but he didn’t actually change the program that much or diverge noticeably from what art institutions in the city were also doing at the time.30 Like Ellin, he drew on the advice of New York dealers, but I think the thing that set him apart was that he clearly perceived the shift in the art world, and Ellin did not. So, if Blum’s changes were not as radical as they appear in hindsight, and if he, like Ellin, eventually abandoned the LA art world, why is his work at Ferus Gallery remembered as a watershed of art culture in Los Angeles?

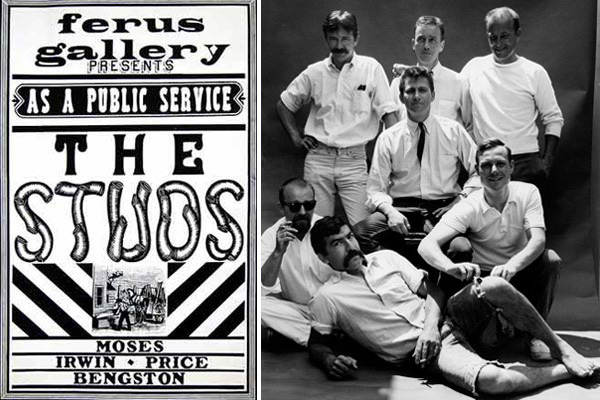

L: Poster for Ferus Gallery’s The Studs exhibition, Los Angeles, 1964. Courtesy of Hal Glicksman. R: Ferus Gallery (Billy Al Bengston, Allen Lynch, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, John Altoon, Ed Kienholz, and Ed Moses, Los Angeles, 1958. Photo: Patricia Faure. Courtesy of the Estate of Patricia Faure.

Irving Blum was not a great innovator; it’s probably more precise to call him a clever opportunist. Guided by his New York dealer acquaintance and with better instincts, he was more perceptive than Ellin about what was going on in American art. He took advice from knowledgeable people, as the story of how he came to show Warhol illustrates. In the early sixties, Warhol—who at the time was putting images from comics in his pictures—was trying to find a dealer in New York. Around 1961, Ivan Karp brought Blum to Warhol’s studio. Shown a Superman on canvas, Blum (perhaps still used to looking at Abstract Expressionist–style paintings) laughed.31 By the following year, though, everything had changed. Leo Castelli—who, by the way, was just developing his eventually metamorphic ideas about marketing contemporary American art32—had just taken on Lichtenstein, and after a second visit, Blum offered Warhol a show, the artist’s first commercial exhibition.33

Blum was also quicker to notice the ties developing between media (slicks or movies or television news), fashion, and contemporary art. Catching the new tilt toward irony, he played with representations of artists—in photographs, advertisements, and gallery ephemera—to promote Ferus and its stable. During the early Cold War era, the Abstract Expressionists had profited to some extent from media image-making.34 Blum (and his cronies) knowingly sent up the kind of photographs of intense brooding artists that had become familiar in the previous couple of decades.

And so it was that Ferus gave us, tongue-in-cheek, “The Studs” and other images of hypermacho artists presented with a California spin. This new photographic convention—made up of so many familiar, indeed evergreen, icons of Los Angeles art of this period—came right out of the battle against the Abstract Expressionists, whose “toughness,” as Warhol called it, went with their “agonized, anguished art.”35

In the end, neither dealer stayed in business. Blum is often singled out as the man whose gallery started it all, and his time at Ferus also left a set of memorable, and still effective, images. He figured out a way to make his gallery appear more convincingly to be part of the bigger national world of images. During his tenure, the collectors he needed to survive were not convinced by his projections, but he had made a start at the beginning of a decade in which, finally, the Los Angeles art world started to catch up, as Andy Warhol later said.36