Allen Ruppersberg: Certain of His Books

by Susan Morgan

California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) co-published Afterall from 2002-2009. This essay was originally published in Afterall 6, Autumn/Winter 2002, and is reprinted with permission from the author. All original formatting has been preserved.

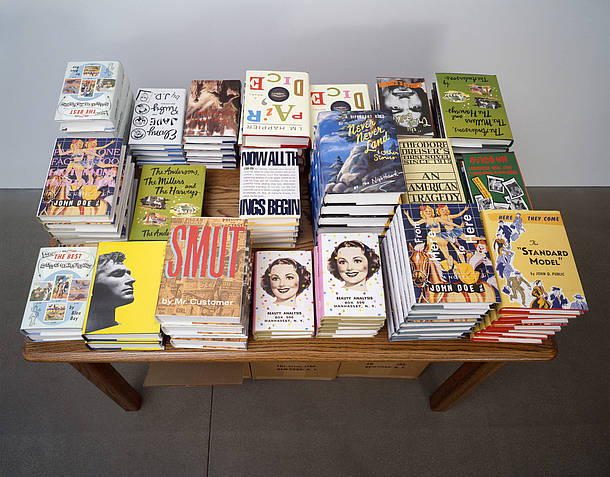

Allen Ruppersberg, Remainders: Novel, Sculpture, Film, 1991, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, T. B. Walker Acquisition Fund, partial gift of Eileen and Michael Cohen

Every good book is essentially a mystery. What secrets might be revealed between the covers? Whose story is it that is being told? Where are we going? How will it all end? Can we ever really understand? Why is so much so easily forgotten? What is it that we are longing to remember?

In the introductory notes to his university lectures on literature, Vladimir Nabokov described his course as a ‘kind of detective investigation’. For Nabokov, the ‘good reader’ is an active reader, a ‘re-reader’ endowed with an impersonal imagination, memory, a sense of artistic delight and a dictionary. ‘In reading a book’, he observed, ‘we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have the eye in regard to a painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy its details. But at a second, or third, or fourth reading we do, in a sense, behave towards a book as we do towards a painting.’

There is a series of anecdotes that the visual artist and uncommonly good reader Allen Ruppersberg has told various interviewers when quizzed about his beginnings and how he found his way into the captivating particularities of his own work. Born and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Ruppersberg was only eight when he decided that he wanted to be an artist. ‘I have no idea where this idea came from’, he admitted to one arts journalist. ‘All I knew was that I needed to get out of where I was, and for some reason I had the feeling that art could be a way to do it.’ His childhood afternoons were devoted to perusing the local library and drawing pictures. In 1962, Ruppersberg moved to Los Angeles, enrolled in a commercial art course at Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), transferred to the fine arts programme and graduated in 1967. His story unfolds plainly. Time passes and one thing simply leads to another. But there are always turning points in a carefully considered story. In 1966 the Pasadena Museum of Art presented an exhibition of Frank Stella’s Protractor paintings and Ruppersberg was astonished. ‘I was completely overwhelmed by their scale, power, sophistication, intelligence – everything’, he recalled to a French curator. ‘I realised I had learned painting in art school’, Ruppersberg told another journalist, ‘but painting had nothing to do with whom I was as an artist and I began all over again.’

For Ruppersberg and his close contemporaries—Terry Allen, William Leavitt and Jack Goldstein—making art was not a choice between sculpture and painting. For these artists – working with film, video, photography, installation, performance, music, audio recordings, multiples, publications, print-making, photography, paintings, drawings and sculpture – it was obvious that art must be made by any means necessary. Somewhere, among the interviews and profiles, I recall Ruppersberg talking more specifically about his own early abstract paintings. I’ve searched for the quote where he states that when he looked at those paintings he wasn’t able to see himself anywhere in the work. I want Ruppersberg to say ‘absent’ for the record but I can’t locate the exact source. I reshuffle my stack of xeroxes and catalogues tagged with post-its but the precise line is lost. The notion of absence, however, is a constant presence in Ruppersberg’s work.

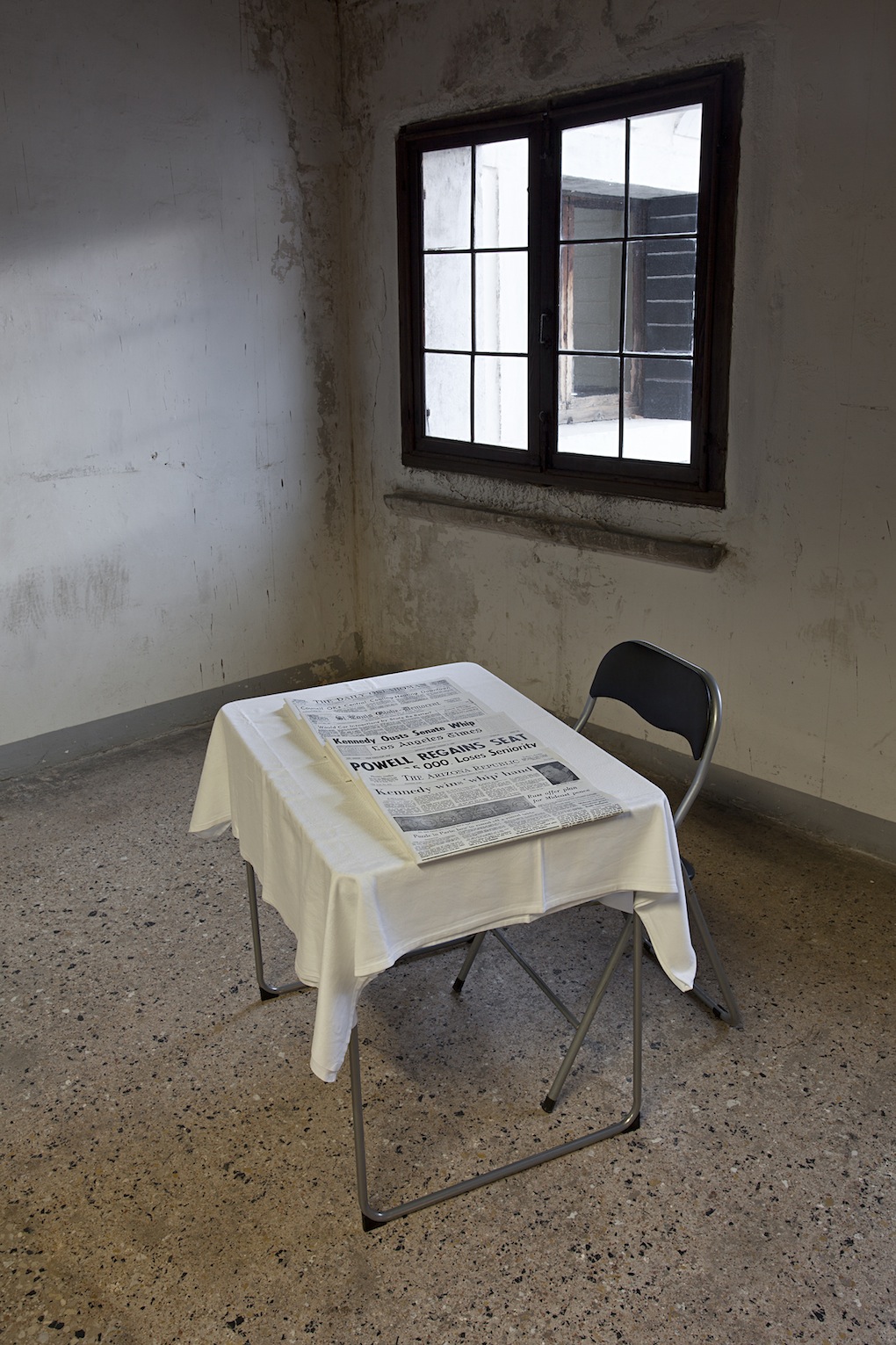

Allen Ruppersberg, Untitled Travel Piece, Part 1, 1969, installation view, “When Attitudes Become Form: Bern 1969/Venice 2013,” Fondazione Prada, photo: Attilio Maranzano

Ruppersberg’s 1969 installation The Travel Piece features a metal folding chair, a folding table set with a square white cloth and four folded newspapers. The daily papers are set at an angle, their mastheads fanned out like cards dealt in a losing hand: four different American cities, two consecutive days, no pairs. It’s a barebones mise-en-scène, the skeletal structure of an undisclosed detective story. What is whispered between the lines? The implications are ominous and banal: a missing person, a fugitive on the run, a region-wide disaster, a bus ride back to Ohio from Los Angeles. Ruppersberg’s 1970 photographic piece, Wave Goodbye to Grandma, is an aerial view of a Southern California hillside. It’s a late summer landscape, a pale-golden tinderbox of parched grasses and a scattering of brittlebushes. A single figure (a long-haired Ruppersberg, dressed in jeans and a white T-shirt) has draped a hand-painted banner—’WAVE GOODBYE TO GRANDMA’—across the ground and turns to look up toward the sky, the distance, the implied departing plane. The image is tense and wistful, a plaintive comedy of elusiveness and loss. Years later, in a 1988 exhibition at Christine Burgin Gallery, New York, Ruppersberg presented a framed full-page advertisement from The New York Times. Plain white text on a black page, it was an advertisement for the film Heaven’s Gate: ‘What One Loves about Life are the Things that Fade’.

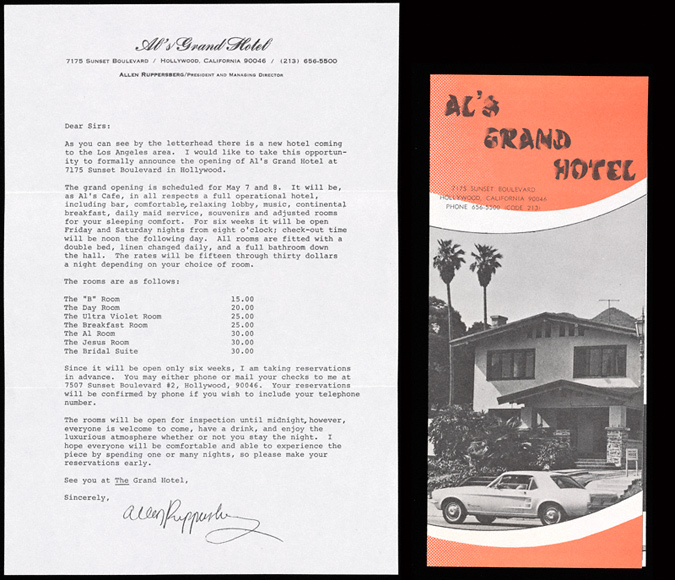

During 1971 Ruppersberg embarked on a major, ephemeral yet unforgettable, project: Al’s Grand Hotel. From July through September (weekends only) Ruppersberg, billed on ‘Al’s Grand Hotel’ letterhead as ‘President and Managing Director’, operated a seven-room hotel. Located in a California Craftsman house on Hollywood’s Sunset Boulevard, each guest room was a themed installation. A Jesus room featured a rough-hewn crucifix felled like a mighty oak and teetering on the edge of a neatly made double bed, a bridal suite was adorned with a bower of artificial flowers and a multi-tiered wedding cake and available for rent, ‘linen changed daily and a full bathroom down the hall’. Above the registration desk, Ruppersberg placed a sign with a hauntingly familiar phrase: ‘Same thing every day. People come. People go. Nothing ever happens.’ It’s a line from German novelist/Hollywood exile Vicki Baum’s Grand Hotel. Originally published as a book, successful as a play and later made into a Broadway musical, Grand Hotel is probably best remembered as the 1932 film in which the beautifully lugubrious Greta Garbo murmurs that she wants to be alone. Grand Hotel – ingenious, wryly humorous, short-lived and microcosmically attentive – was an ideal device for Ruppersberg’s ideas. In the popular film version, Lewis Stone plays Dr. Otternschlaeg, a disfigured physician and hotel resident who pays little heed to the messages left for him at the desk and utters the memorable imperception: ‘nothing ever happens.’ Of course, in Grand Hotel, as in life itself, everything happens. The doctor’s world-weary irony frames a story where everything is lost and found: love and hope, fame and fortune, life and death. ‘What do you do in the Grand Hotel?’, the Doctor asks. ‘Eat. Sleep. Loaf around. Flirt a little. Dance a little. A hundred doors leading to one hall, and no one knows anything about the person next to them. And when you leave, someone occupies your room, lies in your bed, and that’s the end.’

Allen Ruppersberg, letter and brochure for Al’s Grand Hotel, May 2, 1971, designed by Allen Ruppersberg, offset lithograph brochure, typed letter (signed) © Allen Ruppersberg, The Getty Research Institute, Gift of Michael Asher, 2009.

Ruppersberg’s work frequently considers life as a disappearing act. In his 1973 video A Lecture on Houdini, a strait-jacketed Ruppersberg delivers a 33-minute talk on Harry Houdini, the famed conjurer and escape artist. Houdini, born Erich Weisz, took his professional name from Jean-Eugene Robert Houdin, a 19th-century French magician who is considered the father of modern conjuring. The original Houdini was the first magician to perform dressed in evening clothes. He eschewed the traditional wizard’s costumes, debunked secrets of the supernatural and performed magic tricks with everyday objects. Houdini, too, was keen to expose the paranormal, revealing the tricks used by mediums and fortune-tellers. As Ruppersberg informs us in his lecture, ‘When asked to state his occupation he [Harry Houdini] replied: “I am an author; I am a psychic investigator for scientific magazines of the world; and then I am a mysterious entertainer.”‘ Although Houdini was eager to expose ‘mediumistic trickery’, he held on to the hope that there might be communication with the dead. He repeatedly attempted and failed to contact his dead mother and, on his own deathbed, he gave his a wife a message (‘Rosabelle, believe’) that he intended to repeat from beyond the grave. She never heard from him again.

The magic cabinet was a standard prop in Houdini’s theatrical performances: a large box that could be thoroughly examined and declared indisputably empty and then, suddenly—with the tap, tap of the magician’s wand and an open-close-open of the door—a beautiful woman, a befuddled man, or a line of chorus girls would appear. Grand Hotel was Houdini’s magic cabinet on a grand scale. In the film, an extraordinary sleight of fate occurs. Lionel Barrymore plays a downtrodden clerk from a provincial mill town. Diagnosed with a fatal disease, he goes to Berlin in order to spend the last days of life and all his careful savings on a luxurious stay at the Grand Hotel. The debonair John Barrymore plays an impoverished baron turned jewel thief. In the quick course of a few days, the baron falls in love, abandons the heist and is murdered. The meek clerk wins a small fortune, finds a new lease on life, and leaves for Paris with the incandescently young Joan Crawford, an unabashed gold digger. With a tap, tap of the magician’s wand, one man enters to die and another man is carried off into the hearse. Someone is always missing.

Allen Ruppersberg with Harry Shunk, János Kender, Homage to Houdini, 1971, gelatin silver print © Allen Ruppersberg, photo: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust

In Ruppersberg’s 1974 Self Portrait and Sculpture, an ordinary cardboard box is fitted out with a stack of paper, die-cut with the artist’s profile. It’s a negative silhouette, a stencil without features, an empty space stored in a container. Ruppersberg’s outstanding performance as a missing person occurs in the 1972 piece Where’s Al?. Billed as a story written and photographed by Allen Ruppersberg, Where’s Al? comprises one-hundred-and-fifty Instamatic snapshots and one-hundred-and-twenty index cards. Thumbtacked to the wall in a neat grid of banal scenes, the images document a group of friends on a weekend holiday at the beach. They are interspersed with terse dialogue typed out on index cards, for instance: ‘she: Where’s Al?/ he: I think he went back to Cleveland’. Throughout the story, the lowercased ‘he’ and ‘she’ ask after Al, remark on his absence, and speculate on what he might be doing. Al, the only named character, could be at home, hibernating on Sunset, watching a movie, drinking in a dive bar or a legendary soda fountain, on his way to Europe or New York, sidetracked in a second-hand store, reading a book, or injured in a car crash. Al, of course, never arrives. But it’s Al who has composed the story and Al who has supplied the eye and glimpses into the scene. One exchange—’he: Where’s Al?/ she: Maybe he stayed home to read. he: What’s he been reading?/ she: Lautreamont’—is curiously paired with a single image of a nearly unrecognisable young man with long dark hair and a stripy T-shirt, manipulating his face into a hand-made monster mask. The old monster face is familiar: it’s a fright-night favourite, ghoulishly dragging down the eye sockets (with two fingers) and pushing up the nose (with a thumb) for that nasty pig-snout effect. But isn’t that Al? A man, well-steeped in the nightmarish tale of Maldoror, who probably knows that no portrait exists of the elusive author Lautreamont. Or am I reading too much into this?

‘What’s Al been reading?’, he asks. ‘Joan Didion.’, she replies. In 1976, Joan Didion published an essay entitled ‘Why I Write’ in The New York Times. ‘Of course I stole the title for this talk from George Orwell’, writes Didion:

One reason was that I liked the sound of the words: Why I Write. There you have three short unambiguous words, they share a sound and the sound they share is this:

I

I

I

In many ways writing is the act of saying ‘I’, of imposing oneself upon the other—listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. Ruppersberg has said that he wanted to teach himself to write. ‘I had read somewhere that the way to learn about writing is to copy someone else’s work’, he explained, giving a sly misreading to some hoary advice. ‘The same as copying old masters.’ In 1974, Ruppersberg copied out the entire text of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In this elliptical act of translation, The Picture of Dorian Gray, a story famously about a painting, was copied out, line by line, on to twenty stretched canvases. Each canvas – six feet square, a human scale, an arm’s length, the height of man – conveys an inhabited presence, an ephemeral tale becomes an object in the world. Ruppersberg has described each of Wilde’s sentences with their free-standing aphoristic authority as ‘an object’. Nabokov advised his students to plunge deeply into a book, to bathe themselves in it and never to simply wade through the text. Immersed in The Picture of Dorian Gray, Ruppersberg spent solitary hours as a scribe, a scrivener, a copyist in a world seemingly without mechanical reproduction to produce a ‘copy’ of the book, a portrait of its substance without mimicking its style. Language is duplicitous, as the poet Mark Ford points out so wonderfully in his biography of Raymond Roussel. Like Roussel, Ruppersberg chooses plain words that are capable of slithering between meanings.

Allen Ruppersberg, The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1974, marker on canvas, 20 parts, 72 x 72 in. each, © Allen Ruppersberg, photo: Thomas Griesel

Roussel, the author of Impressions of Africa and Locus Solus, was a wealthy French eccentric, a naif who invented an entirely original method for creating narrative. His incomparable influence has been acknowledged by artists such as Marcel Duchamp, André Breton, Harry Mathews and John Ashberry. Roussel, however, revered the popular novelists Pierre Loti and Jules Verne. Treasuring their books, Roussel was known to break apart single volumes and extract favourite sections—so no title page or cover could be seen by inquisitive or judgemental eyes. Alone with the removed pages, Roussel would pore over the text as his chauffeured car circled the city without stopping. A book becomes an object in the world; a collection of frail words and weighty images go for an aimless spin in a deluxe automobile.

Following Roussel’s suicide in 1933, Jean Cocteau published an appreciative and intrigued reminiscence of the writer. ‘One day when I asked him for the “key” to Impressions d’Afrique, he replied, “I will explain it after my death.”‘ Two years after Roussel’s death, a slim volume—no larger than a brief guide of an instructional pamphlet—was published: How I Wrote Certain of My Books. I remember a Manhattan Indian summer afternoon during the 1970s when I met a French artist, a translator of Roussel. The artist, seated at a large worktable in an East Village loft, was eating sardines directly from an opened tin. As he speared the oily little fish with a slender silver pickle fork, he explained the title of Roussel’s posthumously published text. Roussel had wanted to explain the method that he had created to compose some (Fr: certain) of his books; but the author was also writing this book to express the assurance (Fr: certain) that his books would be read widely and, ultimately, live forever. His writing method was thorough-going, original and virtuosic in its renditions of doubt.

Drawn from Life, a title that recurs in Ruppersberg’s work, teases out a similar niggling doubt as to its intended meaning. Is it ‘drawn from life’/ripped from the headlines or ‘drawn from life’/a pencil drawing of a posed subject or a still life? We are always operating from clues – assembling, questioning, sometimes disassembling and assembling again.

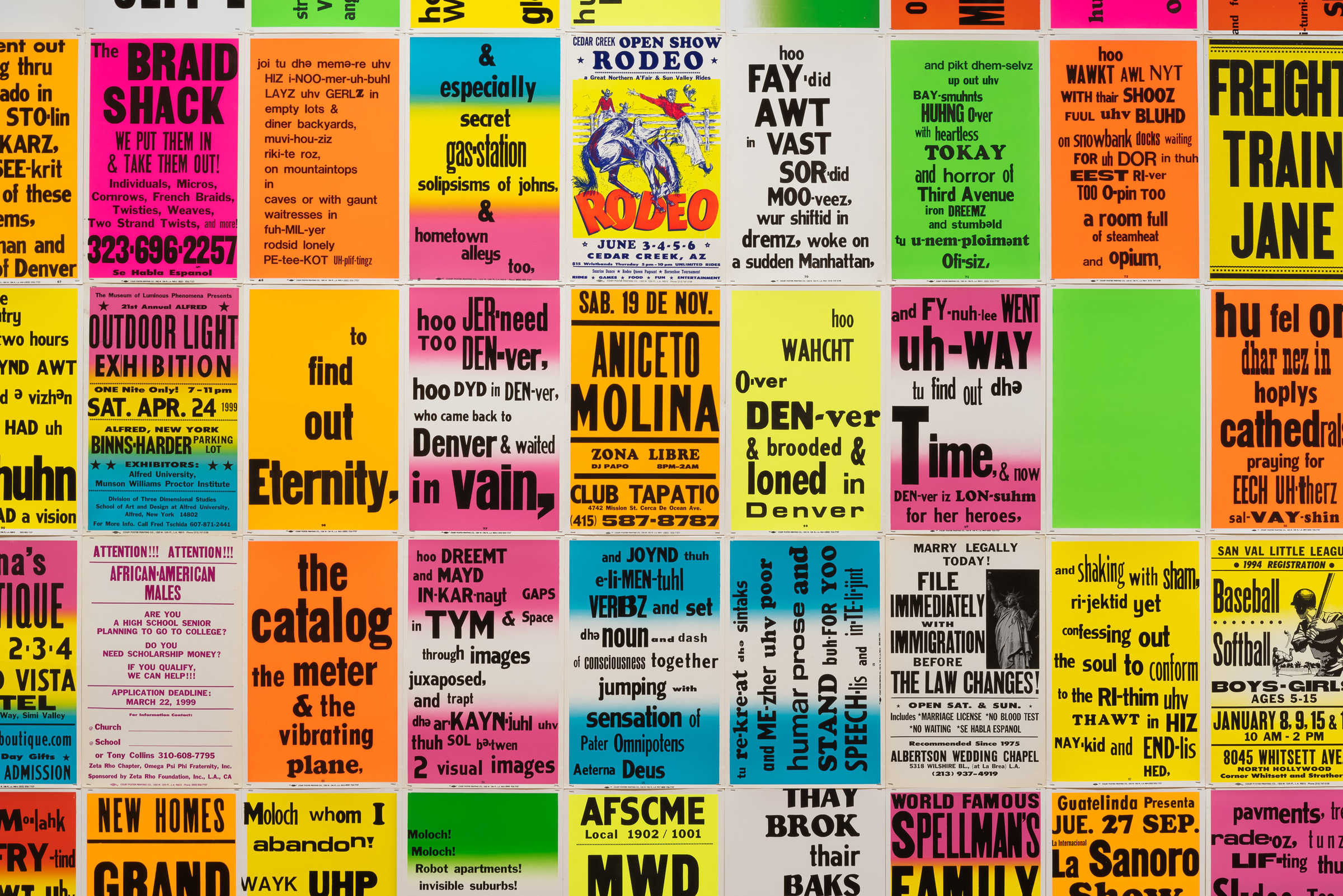

Allen Ruppersberg, The Singing Posters: Allen Ginsberg’s Howl by Allen Ruppersberg (Parts I-III) (detail), 2003/2005, commercially printed letterpress posters, photo: Robert Wedemeyer

Ruppersberg’s work is a transformative action of literature’s classic concerns—the ephemerality of life, the inescapable passage of time, the doubts surrounding knowledge and the unacceptable certainty of death. In his Studies for Bookmarks, Ruppersberg makes precise pencil drawings of newspaper obituaries. These miniaturised biographies—of men who have died from the complications of AIDS—attempt to portray succinctly an entire life in a single newspaper column. Like a banner draped across a landscape, the narrow strips of newsprint have a distinct presence and a wispy sense of impermanence. Ruppersberg’s handmade drawings are consciously infused with a sense of time passing, time spent. Rendered as bookmarks, the obituaries are intended to hold a place, indicate a pause and mark our presence in a continuing story. The bookmarks float at angles on the white page and pale drawings of flowers, wreaths and ribbons adorn the sheet of paper. These spare decorative flourishes share a quality common to the small wood engravings that often appear in 18th-century books. Those small grey images of the natural world that seem to quietly tether the abstract region of words to the earthly world of recognisable images and scenes invite the reader to linger a while on the page.