Game Over: Articulating the Hidden Curriculum

by Jaymee Martin

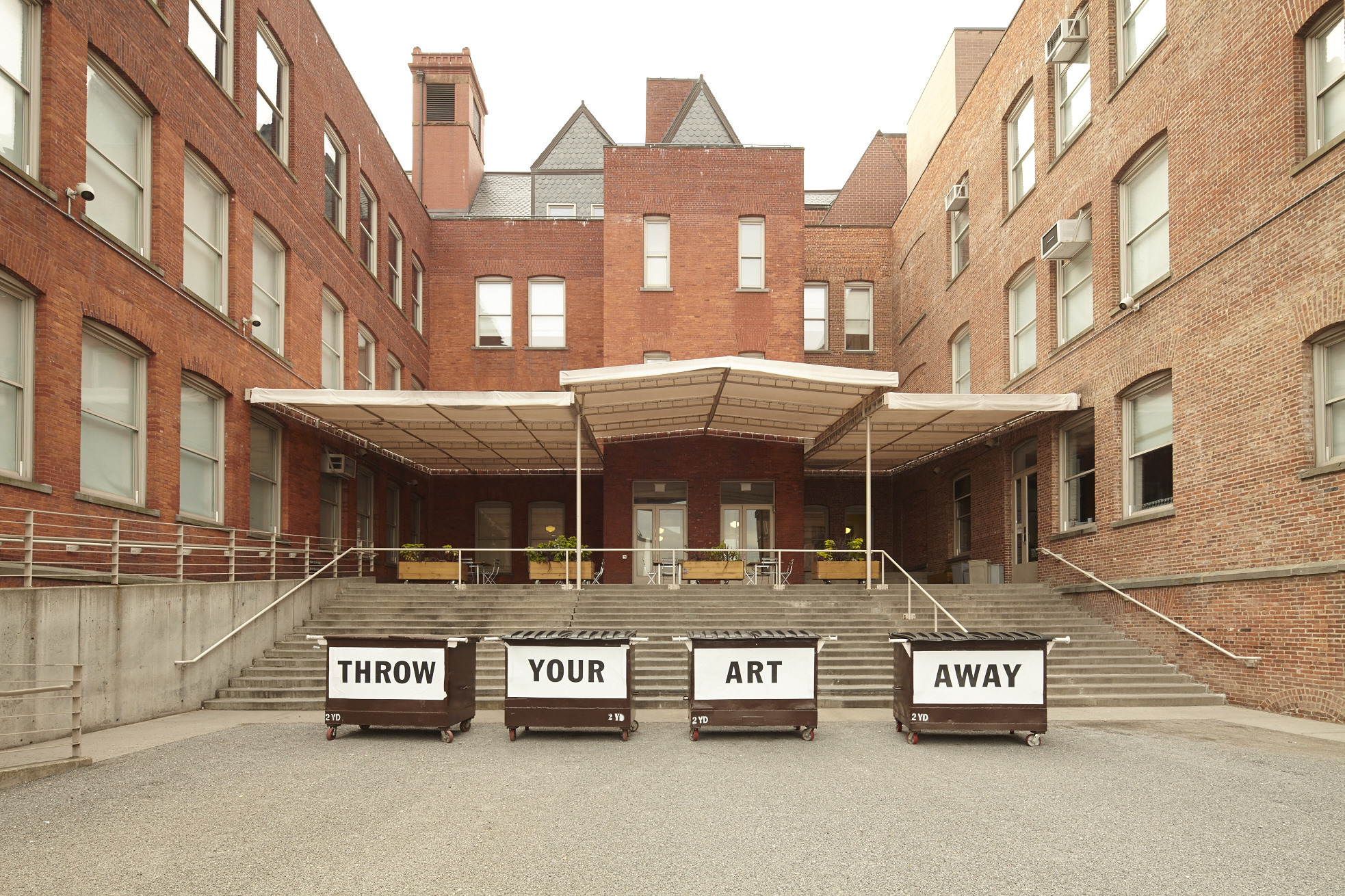

Installation view of “Bob and Roberta Smith: Art Amnesty,” at MoMA PS1, October 26, 2014–March 16, 2015, photo by Matthew Septimus

In my years as a student at a top-tier LA art school, now more than a decade ago, we only spent a single class period openly discussing the practicalities, logistics, and pressures of what a “real” career as a contemporary artist actually looked like. I remember my classmates clamoring for honest advice in an academic environment that seemed designed to hide its internal mechanics behind an Oz-like shroud, pointing us instead to abstract, decoy concerns like semiotics and psychoanalysis. As if Freud or de Saussure could save you when you couldn’t pay your student loans back.

The professor of this particular requisite class seemed like a pretty nice, down-to-earth white guy, so he indulged us, setting aside the agenda for the day to let us put words to the previously unspoken. Many students began to share their plans for after graduation: some wanted to stay in the hustle, go to grad school and get an MFA; others were not so sure. At one point the professor looked at me directly and asked me to tell the class what my plans were. Wearing as much of my heart on my sleeve as I could, I explained that I had been accepted into a master’s program at another top-tier LA art school but would have to take out tens of thousands of dollars in student loans in order to attend. In the meantime, the only “job” I had lined up was interning at a non-profit art space as an assistant to their up-and-coming junior curator, where, a few days before, I had been asked to throw a catered spread of sushi into the dumpster behind the gallery, and instead surreptitiously loaded it into my car.

This anecdote was a roundabout, narrative way of suggesting that the glimpses I’d seen of my future in the art world did not paint an economically or ethically sustainable picture. The only problem was that up to this point I had built my entire life to move in this direction, and I had no idea what else to do.

At the time, I had grown increasingly outspoken about what I was starting to piece together as the moral failings of art school, and in turn the art world it was training us for: namely that there were certain implicit codes of conduct, things you could and couldn’t talk about. For example, if you made work about George W. Bush’s recent “surge” policy in the Iraq War, this would have been dismissed as too obvious, too preachy, too moral—and morals were uncool. However, if you presented even the very same object with a claim to be about “the archive,” for example, this would have fallen completely within the realm of acceptability and praise. Meanwhile, actual people were fucking dying in Iraq, and I was starting to think that we were all accomplices in rendering that violence invisible by carrying on this particular song-and-dance-routine and rewarding those who played by the rules of the game. Little did I know then that this line of thought was inadvertently working me into a position where I’d either have to comply with or disappear from this world altogether, because—as I would later read in the sociolinguist James Paul Gee’s work about discourse communities such as the art world—to renounce it meant to forfeit my place in it.1

Comply or disappear—a poetically apt parallel to the “choice” that, as we finally seem to be realizing, so many women have been forced to make in the face of sexual assault and harassment: to shut up and keep silent and stay in their fields, or to be thrown out, humiliated, punished, erased.

Last year the artist Coco Fusco described the art world and especially art schools as “the perfect place for sexual predators,” citing decades of experience as a professor to support her claim that despite the prevalence of abuse and its unsurprising nature to anyone who has ever been involved in an art school, very few people—from students to professors and administrators—ever speak about it. Knowing that one of her female predecessors had been squeezed out of her job after complaining about a male colleague’s behavior, Fusco reflects, “we knew what would happen if we talked.” Meanwhile, art students learn their place within these power differentials by staying within a culture of rumor, a whisper network through which news travels but isn’t spoken of openly: “At top-tier schools, where the ties to the art market are most pronounced, students learn quickly that their professional success is linked to their willingness to play by the rules.”2

All this is leaving out the fact that I was privileged enough to be let in to begin with. Between 2006 and 2008, I had only one Black classmate out of more than a hundred. She showed a razor-sharp awareness of this fact by referring to herself as “Token” and employing explicitly racist symbols such as watermelon in her artworks. Some were confused about why she was so confrontational, when racism was pretty much over and besides, we were the good guys, not the racists—while in truth, we were inexcusably blind at best, silently complicit at worst, to the deeply entrenched institutional racism that resulted in hers being the only Black voice present at all.

Chris Kraus, writing in 2000 about the rise of Los Angeles art schools and the MFA as a key to art world and art market access, addresses the racist double standards hidden within the rules of the game. Citing the positive critical reception bestowed upon a young white male MFA graduate for a work in which he spray painted the words “Fuck the Police” on the installation walls, she writes that “if a Black or Chicano artist working outside the institution were to mount an installation featuring the words ‘Fuck the Police,’ I think it would be reviewed very differently, if at all. Such an installation would be seen to be mired in the identity politics and didacticism that, in the 1990s, became the scourge of the LA art world.” It’s the same attitude that prompted a white male Los Angeles Times critic several years earlier to dismiss work by Black artist Isaac Julien as “myopic and opportunistic,” “conservative,” and “contend[ing] that the social group the artist belongs to is more important than the work he makes.”3

I understand that things have changed in the 18 years since Kraus made this observation and the 10 years since I left LA. Thanks in very large part to the Black Lives Matter movement started by women of color, conversations about racism, police brutality, and privilege have surged urgently into the open on a national scale. But the fact that it took so long for these conversations to reach the art world and that Kraus’s words held true for basically 20 years, is damning. Police shootings of unarmed Black men were happening regularly back then too, and certainly nobody in art school talked about Sean Bell being killed by police on his wedding day in 2006 despite the widespread media coverage the story received. There were no Sean Bells in art school. It was not “our” issue, or so we thought.

And since it wasn’t our issue—not a legitimate, sanctioned issue according to the rules of the game — how could we speak of it? Remember, our “professional success is linked to [our] willingness to play by the rules,” to return to Fusco. Better to stay silent, better not to risk exclusion and being dismissed as conservative, moral, or uncool. All the while our silence functioned as a tool to keep the perpetual violence out of our view and exempt us from having to address it.

Silence speaks as much as language does. We only spoke about the practicalities of an art career during one class period, but exactly what invisible, implicit social contract was keeping us from speaking about it more? Two of my former classmates directly mentioned this implicit social contract when I interviewed them several years later as part of a research paper on sociolinguistics, education, and discourses (bold mine):

1. During my time at [LA art school], I found very quickly that perhaps the most important things I could learn about how to be an artist would not be told to me outright. The value of implicit learning was primary. I felt that if I could exploit an ability to intuitively observe and remember the various social codes and languages that my educators represented to me and to their friends and colleagues, I could learn about what it was to be a successful artist. As they had created for themselves particular styles of address, modes of personal comportment and working theoretical understandings that related to their practices, it seemed to be critical to model this for myself as I proceeded in my attempts at making things (learning how to make things).

2. I learned very little about ‘how to be an artist.’ In fact, the faculty at [LA art school] takes a firm stand against teaching one how to be an artist. Instead, they teach you how to participate in a discourse. The ‘artist’ component is taken as a given. We were treated as though we already knew how to be an artist, or that we’d figure it out along the way.

My classmates’ observations about “implicit learning” and “how to participate in a discourse” echo art historian Howard Singerman’s thesis in his book Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University. He posits that in contemporary art schooling, students are no longer trained how to paint or hone technical skills, but rather how to position their identities within the discourse of the art world. He writes, “The art department provides its students with … tacit knowledge of the rules and orders of practice. It is part of a network of institutions—galleries, museums, granting agencies, journals, and the like—that define the boundaries of the field, construct the concerns or shared values of the community, and circulate its discourse—the language that marks its speakers as members of a community.”4 Just as art school disciplines students to only speak about what can (and cannot) be spoken of, it also socializes them at the level of language, that is, in how to speak: “Its rules concern what can be said, and in what form.”5

It is no coincidence that both Fusco and Singerman focus on art schools, which have long been primary sites for socialization and discipline. Education scholar Philip W. Jackson coined the term hidden curriculum in 1968 to describe what my classmate called “implicit learning” and Singerman called “tacit knowledge”: the unspoken social and cultural norms, values, and expectations that schools transmit to students apart from the official, formally taught subjects. The Glossary of Education Reform defines the concept of the hidden curriculum as based on the recognition that students absorb lessons in school that may or may not be part of the formal course of study—for example, how they should interact with peers, teachers, and other adults; how they should perceive different races, groups, or classes of people; or what ideas and behaviors are considered acceptable or unacceptable. The hidden curriculum is described as ‘hidden’ because it is usually unacknowledged or unexamined by students, educators, and the wider community.6

So, although no art school professor points at a whiteboard in a room of furiously note-scribbling students and says, “To be a real artist, wear more black, and also remember that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. does not count as high theory but wife-killer Althusser totally does,” these lessons are nonetheless transmitted and learned. And because the very fact of their transmission is hidden, they are rarely, if ever, scrutinized or questioned.

The hidden nature of this learning also makes it virtually impossible to detect when it’s happening in real time. Certainly, in my own case, I did not see how deeply I was internalizing the rules of the game, how wholly I was replacing the personal language I’d developed before art school with the sanctioned discourse. Looking back at an artist statement I produced in art school, I can see that all markers of my personal aesthetic were gone, replaced by trendy French philosopher quotes and jargony words like “criticality” and “articulation.” My transformation from outsider to insider was most apparent in my language.

Singerman continues, “The task of art schools across the country is to provide a language that we can speak together as professionals, and to ensure that its concerns will be the students’ concerns. The student’s task … is to take—and to mark—his or her place.”7 In other words, if I as an outsider wanted to achieve the reward of becoming a recognized, visible participant in the dominant discourse community—to mark my place in the art world—I had no choice but to take on its values and adopt its language, even if it meant compromising my own language and values at a degree so subtle and insidious I could not even see that it was taking place.

At this time I was starting to sell my work to a collector, was about to get into that graduate program, and was on my way to graduating with the highest GPA in the art department. This is not to say that the art world doles out rewards based upon objective notions of artistic quality, nor, as I look back at that artist statement, even upon the criterion of making any fucking sense. Rather, my rewards came for mastering the language and internalizing the rules of the game, for being fully and correctly socialized into the discipline and subtracting any language or values that were at odds with it.

Much of hidden curriculum scholarship focuses on how language specifically functions in schools as a weapon to strip students of their own personal or cultural identity and impose a dominant discourse. This history ranges from decades of boarding schools subjecting Native American students to beatings for speaking anything but English to one Texas school making its students write “I will not speak Spanish at school” on slips of paper that were then buried outside in a wooden box during a metaphorical funeral for “Mr. Spanish.”8 One contemporary scholar, Angela Valenzuela, uses the term “subtractive schooling” to describe the systematic stripping down of language and identity as students undergo a process of forced assimilation to the dominant culture.9

My experience in art school is clearly benign compared to the horrific violence of the Bureau of Indian Affairs or the deep-seated institutional racism in Valenzuela’s studies of Mexican-American high school students. So I guess the next question is, who the hell gives a shit? Art school is nowhere near the world’s biggest problem right now. Yet here I am ten years later and these ideas have not left me, because somewhere inside me this all still matters. Because, while the consequences differ, all these examples fall on the same spectrum of how personal identities are subtracted and dominant discourses are imposed for the sake of, in Jackson’s words, “institutional conformity.” And if losing whole swaths of myself and my artistic practice is wrong—and I know from firsthand experience that it is—then this whole spectrum must be wrong, and we should talk about it.

Because after all, isn’t art supposed to be a site for the exact opposite of institutional conformity? At least that’s what I felt when I decided to become an artist as a teenager, after reading books about Marcel Duchamp and conceptual art—that art’s most electrifying potential lay in its power to challenge conformity, to push at the boundaries of the status quo, to question entrenched beliefs about what both art and life could be. Certainly, this liberating sense of a blown-open playing field is what has kept both Duchamp’s and conceptual art’s historical influence so potent and present for decades: the idea that art can be anything, not only what has been previously accepted or defined as art.

Yet art school—with official curricula that continue to explicitly teach the lasting reverberations of Duchamp, the dialectical history of the avant-garde, and art’s relationship to 20th century emancipatory political movements—sends a message about art’s revolutionary potential that is fundamentally at odds with how its hidden curriculum trains students to comply or disappear. Ultimately, the formal curriculum’s values of experimentation and boundary-pushing clash with the hidden curriculum’s subtractive, unspoken socialization to rules of the game: sure, art ideas and objects can be avant-garde, revolutionary, or political, just so long as any threat posed to the status quo is cosmetic and not real.

“Guilty as charged,” I think when I read this excerpt from artist Andrea Fraser’s 2012 essay “There’s No Place Like Home”:

Much of what is written about art now seems to me to be almost delusional in the grandiosity of its claims for social impact and critique, particularly given its often total disregard of the reality of art’s social conditions. The broad and often unquestioned claims that art in some way critiques, negates, questions, challenges, confronts, contests, subverts, or transgresses norms, conventions, hierarchies, relations of power and domination, or other social structures … seem to have developed into little more than a rationale for some of the most cynical forms of collaboration with the most corrupt and exploitative forces in our society.10

At the end of art school, I attempted to point out this contradiction and my own complicity in it by asking the professor of the requisite class to fail me, as art. In critique, when one student broke with the generally disapproving group to say she saw this as an act of resistance, another student tellingly countered, “But resistance has been done!” Pierre Bourdieu describes this as “an objective collusion”—since critiquing the rules of the game positions one as outside of it, anyone who wants in must buy into the perpetuation of the game’s definition of legitimacy, constantly reproducing the status quo ad infinitum. Calling the rules into question threatens to existentially derail the game itself, because after all, “What would become of the literary world if one began to argue, not about the value of this or that author’s style, but about the value of arguments of style? The game is over when people start wondering if the cake is worth the candle.”11

Given the choice to comply or disappear, I ultimately opted to drop out. Since leaving, I’ve wondered if believing that comply or disappear are the only two options is itself a function of the game. Maybe if we refuse to adopt the dominant language and values that keep us silent about so many things that matter—including our very selves—we can change the rules, from the outside in.