Artists at Work: Fiona Connor

by Thomas Lawson

Artist Fiona Connor at Laurel Doody, March 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

From April 2015 through April 2016, artist Fiona Connor ran Laurel Doody, an experimental exhibition space, out of her apartment-studio on Cloverdale Avenue in the Mid-Wilshire district of Los Angeles. Over the course of this year she produced six exhibitions that lasted a month or longer and several events. This interview, in which Connor discusses the Laurel Doody project, was conducted in another Silver Lake apartment in early September 2016.

Thomas Lawson: Let’s talk about Laurel Doody. What I’d like to do is start with the idea, and how it came about. Then we can talk about the space itself and the shows you put on there.

Fiona Connor: I guess there was a series of visions that ended up being realized. First of all there was the apartment. I knew the space I was going to move into would function as my home and studio, and since presentation is always an important part of the work I make, that was always a consideration. The apartments in that building are from a particular time, with that mid-century feel, beautiful windows, and the streets are lined with trees. And so when I first saw it, it was like, “This is a great place to show work.” There were several artists in the area, and it was close to LACMA and Museum Mile, so it felt quite ducky. It just had an atmosphere—ducky-like. Ducky, like the rubber duck in the bath. Ducky. Kind of cute.

But a really important starting point was much earlier, when I was involved with artist-run spaces in New Zealand. There was this one collective in particular, Gambia Castle, that had nine members—we met every week and presented exhibitions of our own work, and we all paid for the space. We all had total agency. It was just a really positive experience and it felt like a good model. Then I came to L.A., and I remember even as I touched down I was thinking, “I want to do something similar here.” But I had to wait till the time was right, until I’d done my own studies and kind of put my feet on the ground.

637 South Cloverdale Avenue, Los Angeles, CA, 2015

TL: So when you found this apartment you had this idea about working collaboratively in some way with a group of artists and with the space?

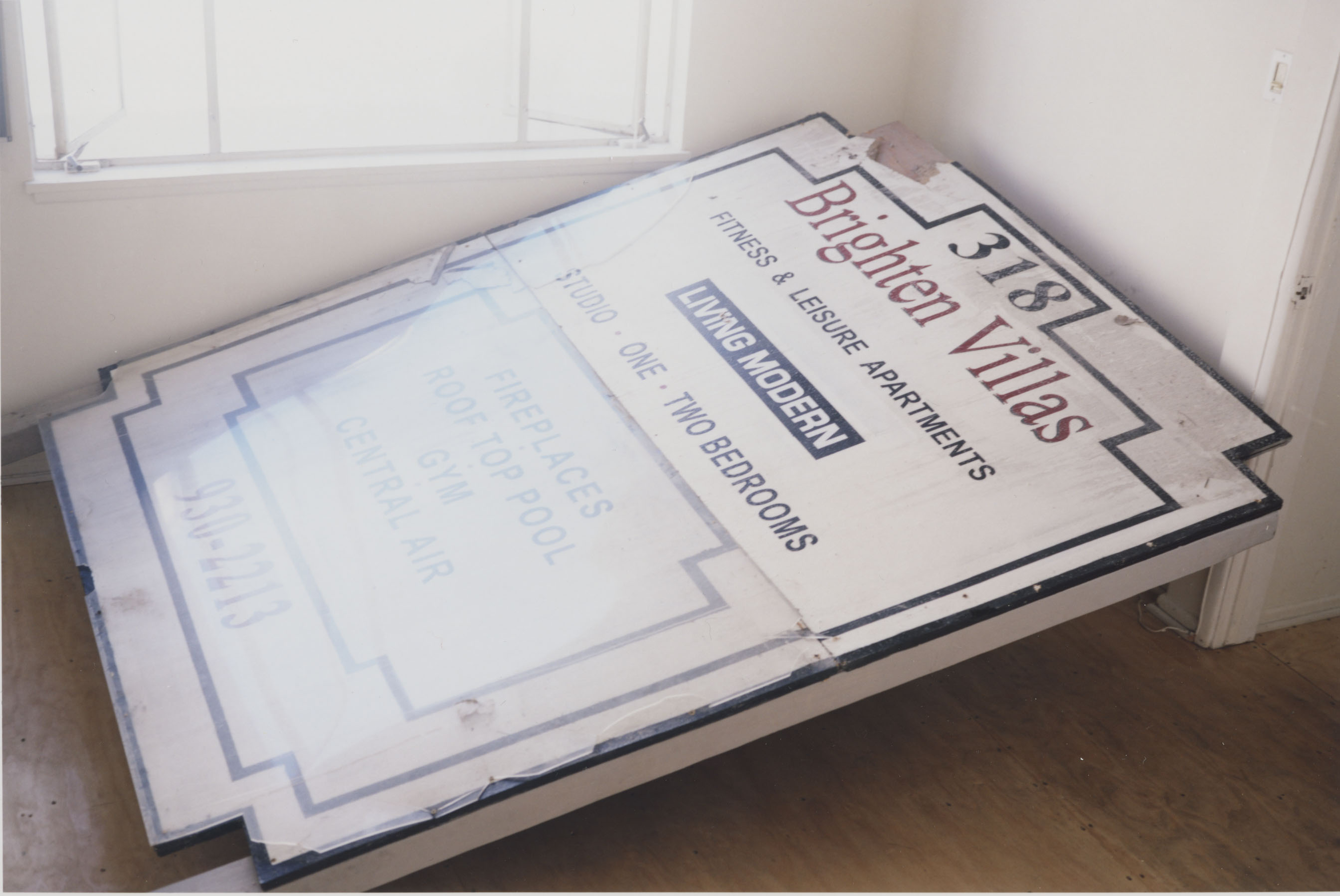

FC: Yeah. I started using my studio and then started having shows there. I removed the furniture and presented a group of real-estate signs from the neighborhood—a body of work called Signs that change buildings—and it became apparent that I needed to formalize the whole thing as a project space. I was finding that I just wanted to see serious projects by certain people in L.A. and give them the control so that it could be like they wanted. Plus, I wanted them to be paid an artists’ fee. I just wanted it to be a great experience. [laughs]

I ended up producing a lot of the exhibitions. I would arrange for framing in exchange for a work, or get a deal from the place that makes bricks, for example. That became a project itself—it just brought me so much joy to put together a program of stuff I was really compelled to present and believed in.

Fiona Connor, Signs that change buildings, 2013, photo: Andrew Gohlich

TL: How long did it last? Was it a year?

FC: It was pretty much a year to the day.

TL: Was that part of the concept or just the happenstance of the lease?

FC: No. I wanted to do something for just one year.

TL: Did you, at the beginning of the year, know who you would work with?

FC: Well, I think six months out, I wrote a list and approached and invited people, bar the final show and the final event. Asking people way in advance meant that we could be ambitious. People could travel and grants could be applied for, and these conversations could develop.

TL: You applied for grants for people, or did they just apply themselves?

FC: They applied for grants and I wrote letters of support.

TL: I’m just trying to understand because I think it’s interesting you created a model that included that kind of production help and fees.

FC: Yeah. That was important because part of idea was no sales. No sales of exhibitions. I was really firm about that. I didn’t want the conversation to veer into the concerns of saleable work, whether it would be movable, whether it be appealing to certain people. I just really wanted it to be about the exhibition.

TL: Then you had to raise some money?

FC: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I fundraised for the costs of the project, and the artists fundraised by themselves for extra money. The budget included the artist fee, the rent for the space, some of the costs of hosting. It was as if Laurel D. became this character who did all these things that I wouldn’t be able to do. She wrote checks to her friends! [laughs] She kind of just got to do all the things that I wished I could do. I love mail-outs and posting stuff, so Laurel Doody had a very extensive postal service. Many of my people weren’t in L.A., so the mail-outs went across the world and they’d get a version of Laurel Doody in the post.

TL: It is such a striking, very particular sounding name that I forgot to ask: Who is Laurel Doody? Where does she come from?

FC: She’s a family friend, a friend of my mother’s and a mother of my friends. She was this kind of magical character when we were little. Always had gum in the car and when you visited her, she’d always make you feel like it was just-you-and-her time. She was such a great host, always so focused and amazing. I wanted to evoke the way she did things, the personal touch.

TL: Cool. Does she know about it?

FC: Yeah. We had dinner recently in New York—that’s where she’s from—but she never made it to the space. At first I had asked her if it was alright to use her name, and she was like, “sure, whatever.” But then when it started to have a presence, I think she became quite shy. We had a conversation about it in New York and she said, “Please. Call me something different when we’re out in public, because people are treating me like they know me.” And I was like, “Oh no! It’s the opposite! I was really wanting to honor you and to celebrate how cool you are.” Overall, I think she saw it as a compliment.

TL: You also mentioned that there were board members? That’s a fairly serious sort of structure.

FC: Right. We had a board. I mean, the board was just people I felt I could have an honest conversation with about this space and get some feedback, you know? The board didn’t meet regularly. We tried to but I think only two members lived in L.A. I had wanted there to be a social aspect to it, and knew that everyone would get along and have fun together, but it just ended up being a little too ambitious, I think.

All the components of the gallery were treated as authored works—the website, the photography, the floor plan; the things that get done that are just part of putting together a gallery.

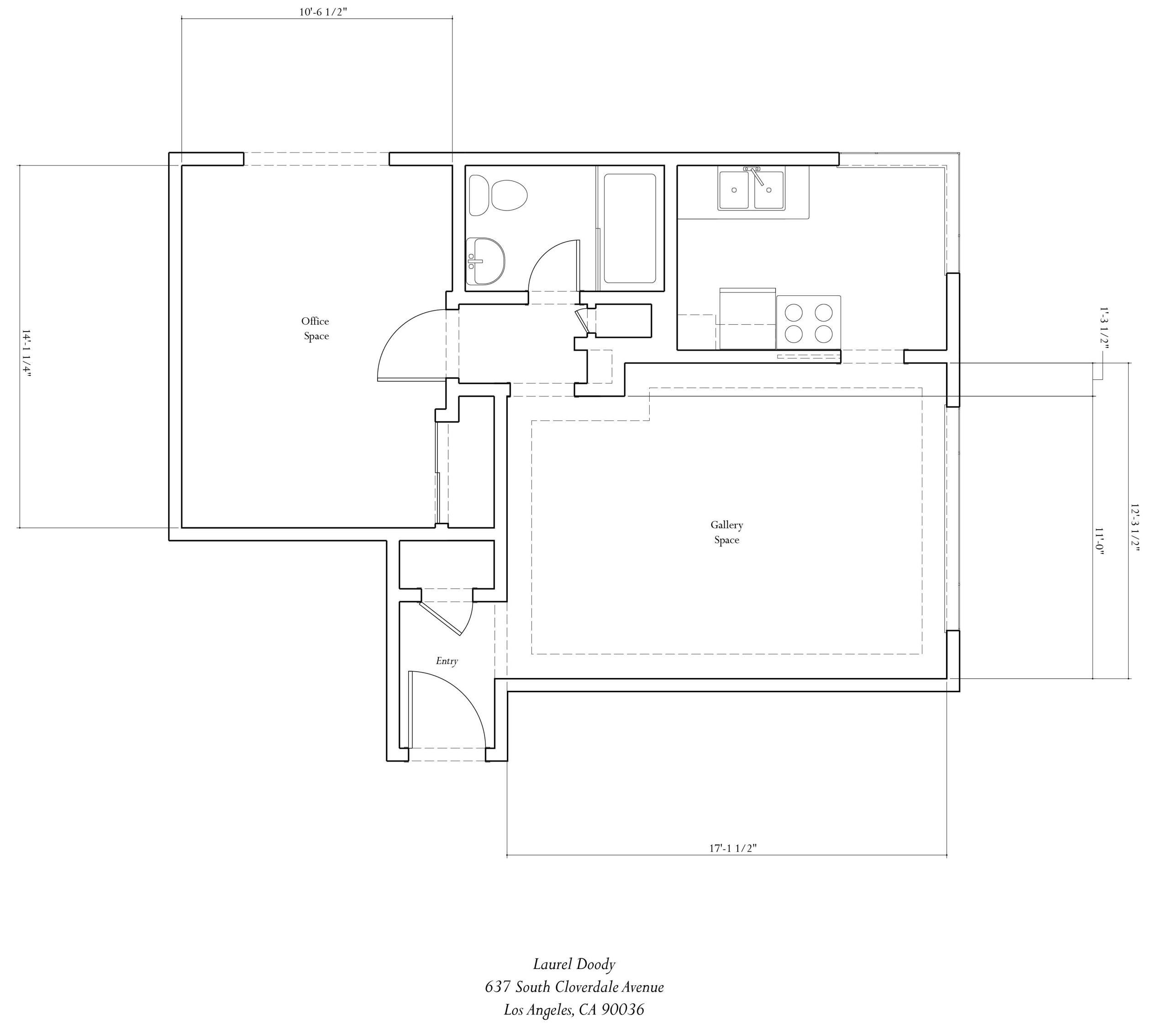

Laurel Doody floor plan by architect Erin Besler

TL: What do you mean by the floor plan?

FC: Literally measuring the space and then making a document, a drawing of the whole space. It was made by the architect Erin Besler and distributed to artists as they began their project.

TL: Let’s talk about the shows. The first show was called “A Short Line Between Three Points” and included work by Matt Hinkley, Aubrey Tigan and Karl Wiebke. It was curated, but not by you?

FC: Right. It was curated by Quentin Sprague, who I’d gotten into a conversation with after seeing a show he did in Australia. He had worked in Australian Aboriginal communities and was questioning how the work that was being produced in these communities was being categorized and presented. So I thought it would be interesting for him to present a show in a more private place, outside of a formal institutional framework, somewhere that he could just do it as he wanted.

“A Short Line Between Three Points,” curated by Quentin Sprague at Laurel Doody, April 25–May 31, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

TL: Can you talk about what he did?

FC: He brought over three small works from Australia, and then we added some exhibition seating—two low-slung leather chairs by the Brazilian modernist Sergio Rodrigues. And the sisal on the floor, which ended up coming in and out of the space throughout the year, was first installed for this show.

One of the pieces was a work by Aubrey Tigan, a talisman—carved pearl shell with ochre. He was an Aboriginal artist who learned his way of working as it was passed down through his family. Traditionally these objects were functional objects, something like maps, but this piece was made within the more recent context of the contemporary market for Aboriginal art. The story of contemporary Aboriginal art in Australia is so interesting and specific as it has been developed in cahoots with the market there. It’s the biggest art market in Australia. It’s so fascinating.

Left: Aubrey Tigan, Honest Man Rigi, 2010, incised pearl shell, ochre. Right: Matt Hinkley, Untitled, 2014, polymer clay. Photos: Fredrik Nilsen

So there was that object and a piece by Karl Wiebke, a German artist who moved to Australia in the 1980s. And then there was Matt Hinkley, who had this small carved work that related formally to patterns in Australian aboriginal paintings.

The three objects were presented on the wall in a line. There was no clear categorization, installation-wise, although there was a list of works and a transcribed conversation between myself and Quentin. We provided seating with these amazing Sergio Rodrigues chairs, which were on loan from Jane Berman and originally belonged to Ed Janss, who also collected a lot of indigenous art. But they had fallen into disrepair. Jane wanted to restore them, and so, with her permission, I restored and included them in the show, layering in a conversation about modernist design and local materials. Plus they are so comfortable and welcoming.

I had been itching to work with these chairs. I’d actually proposed to do a project with them at the Fowler Museum at UCLA. I was asked to design seating for the foyer but it did not end up happening. So with this opportunity I was like, “Awesome. I get to touch them, work with them.”

TL: I like the way this all sets up a conversational situation but doesn’t demand anything. There are these three objects on the wall that may or may not relate to each other. Then there are the chairs, which have an intense presence and a complex backstory. And we are left to sort out any possible relationship between these two aspects of the presentation, and, in an interesting way, our relationship to the space. Are we visiting or viewing?

FC: I think at Laurel Doody, hosting was a huge thing, offering people a drink if they wanted it. I think that hosting and conversation became part of it. People would end up staying a long time.

Artist Daniel Malone and Peter Kirby at Laurel Doody, 2016

Of course, I understand people who didn’t want to stay, but I almost think that people wouldn’t come because they didn’t want to hang out. [laughs] Like, “I don’t want to talk today.” The social aspect is not something that can usually happen at a gallery when you walk in and expect to leave in 10 minutes.

TL: Right, that is an interesting aspect of the project, because the standard experience of going to a gallery is just in and out; you’re kind of hoping no one is there. [laughs] But with Laurel Doody the whole idea was that there would be a conversation, maybe even a cup of tea or something.

FC: Exactly. I think hosting was a huge part, certainly for me.

Even just getting ready today for you to come was— I just love it, you know? Just cleaning the house, preparing a little bit of food. It’s just such a nice thing to do. [laughs]

TL: I have to admit, driving over I was thinking, “I wonder what kind of little snack there might be.”

Ok, so I think the next show was Keaton Macon?

Keaton Macon, “1:1:1,” installation at Laurel Doody, July 19–August 16, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

FC: Keaton’s was an important show because he was—

TL: Was he in school [at CalArts] when you were?

FC: Yeah, but we weren’t really close at school. But at some point he told me about this long-term project that he was working on and it really struck me as very important—to him, obviously, but also to everybody who lives in LA. He was making sound recordings from different sites around LA, places with different kinds of resonance. These were hour-long recordings, and he had one for every day of the calendar year, although he took three years to finish the entire project.

He started by going to specific sites pertinent to the history of LA, I think just to get things going. There is a photograph of the damage done when the St. Francis dam broke and so he went up there to record ambient sound. He stood on the corner where a famous photograph of the Watts riots was taken. He would make these sound recordings of sites with different kinds of historical relevance, places he identified as being singular places in the city. Over the three years, it became looser, and by the end he just would sometimes record himself watching TV and eating pizza. He gave every tape a name. One was called Dragnet. One was called Rain. That was the word that stuck in his mind after he did the recording.

Keaton Macon, Data Recovery, 2013–15, custom furniture, tape player, 366 cassette tapes, installation at Laurel Doody, July 19–August 16, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

The final work contains 365 hour-long audio tapes, and Keaton wanted people to listen to them without headphones, to take a tape from the series, put it in a tape player, and listen to it in the room with the sound filling the space. So that posed a big problem for the galleries he was approaching. That was when I decided it would make sense to present it at Laurel Doody. And it was important for me too, to more directly root the program in Los Angeles.

TL: That makes sense, since many of the artists you worked with were from New Zealand, like Kate Newby.

FC: Kate was part of the original collective in New Zealand before she moved to New York. Kate is an artist that I feel very connected to. [laughs] We went to the same high school. Kate was on the board of Laurel Doody, as one of my advisors, and she edited the newsletter with me. So when she moved to New York, I said, “Now you’re in America. I want you to do a serious project in LA. I want it to be something that you can stand beside,” because group shows are just so compromised, you know? Especially for someone like her, who works in installation.

Kate Newby, “Two aspirins a vitamin C tablet and some baking soda,” installation at Laurel Doody, October 18–November 22, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

She arrived and we sat in the space the first day, just sat on the floor and talked about what we wanted to do and did some drawings. Then we ripped up the carpet and put it in storage. The show happened over two weeks of intense work. I had this relationship with a brick plant down south, in Lake Elsinore, because of this research I’d been doing about bricks at UCLA. They told me they would like to collaborate on an artwork, and Kate was into that idea.

The next day we traveled to Lake Elsinore and started working in the brick plant, carving and embedding and making this brick floor. [laughs] She had brought all these pieces from New York that she’d done previously—components or little precious things—and she embedded them in the bricks. She made tools to dig into the unfired bricks. The tools were cast in pink silver and later placed in the bedroom. There was a wind chime outside the kitchen window, and handblown pieces of glass on the ledge outside. That happened over two days, I think. We went to the brick plant and stayed at some weird AirBnB that was very spooky, and then we did all the brickwork and came back up to LA.

Kate Newby, “Two aspirins a vitamin C tablet and some baking soda,” installation at Laurel Doody, October 18–November 22, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Then there’s this aluminum caster here—do you know Alphacast? They’re incredible. You give them any object and they sand cast it in aluminum. They’re fantastic. Kate took a box of leaves and sticks from the streets around Laurel Doody and had them cast. We went back down to Elsinore the next day, came back, installed the show, and opened it—she called it Two aspirins a vitamin C tablet and some baking soda. She flew to Mexico City the day after the opening. I think we both work like that. High energy.

In a way, she was quite violent in the space, in that she made big changes. She ripped up the carpet, installed a brick floor, then poured wax on the floor. That was when the problems with the neighbors became glaringly obvious! Every show occupied the space and had an attitude—I mean all the shows had a very palpable feeling to them. Living with them, you really got to know the work. And in LA there’s a long history of people doing gallery-type projects in their houses.

Kate Newby, “Two aspirins a vitamin C tablet and some baking soda,” installation at Laurel Doody, October 18–November 22, 2015, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

TL: One of the first times I ever came out here was to do a show with Richard Kuhlenschmidt, who had a small gallery showing new art.

FC: Is this the guy in the apartment?

TL: He was in a basement apartment in Los Altos, a fabulous, Spanish-gothic-with-a-Deco-touch apartment building maybe a couple miles east on Wilshire from Cloverdale, closer to Wilton.

FC: That’s so cool you did a show there.

TL: It was the same kind of thing you are describing. I flew in from New York, installed the show, then slept in the gallery. At night, the gallery became his apartment, the desk became the dinner table, stuff came out of storage. Then in the morning, we had to get up and put it all away. He had a total system down for clearing the space, making it seem like a pristine gallery. It was amazing.

FC: I think about the way that living with the work—it was such an awesome year. It was definitely immersive. You wake up and it’s like all those conversations feel so intimate, you know? I don’t know but seeing people respond to stress, all the uglinesses and the strengths, it’s just fascinating. I was so completely immersed in the project, but it also allowed me to do my own work in the margins, setting up the table from Monday to Thursday. Somehow that worked, you know?

TL: And then the project you did with Daniel Malone allowed you to combine the two—to work with someone on an exhibition for Laurel Doody that was also something you were more directly involved with.

FC: Yeah. It was collaborative show with Daniel Malone and it had a really long name: Not a Dated Annotation (Designation of Will Within the Season Which We Live). It started out as a historical show. Before Laurel Doody, I wanted to do a show that developed out of the research that you and I did with The Experimental Impulse because I so enjoyed that process. I felt like I wanted a bit of that in my life.

The Experimental Impulse—the class at CalArts and the culminating exhibition at REDCAT [both part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative]—started with research into the ways that late 1960s counterculture related to conceptualism in LA. And at the time I was working on that, Daniel was doing similar research in Poland, proofreading and republishing English texts from Polish art history. So there we were, two artists from New Zealand, working with recent art histories as a way to get grounded. It just felt so weird that we’d both done the same thing.

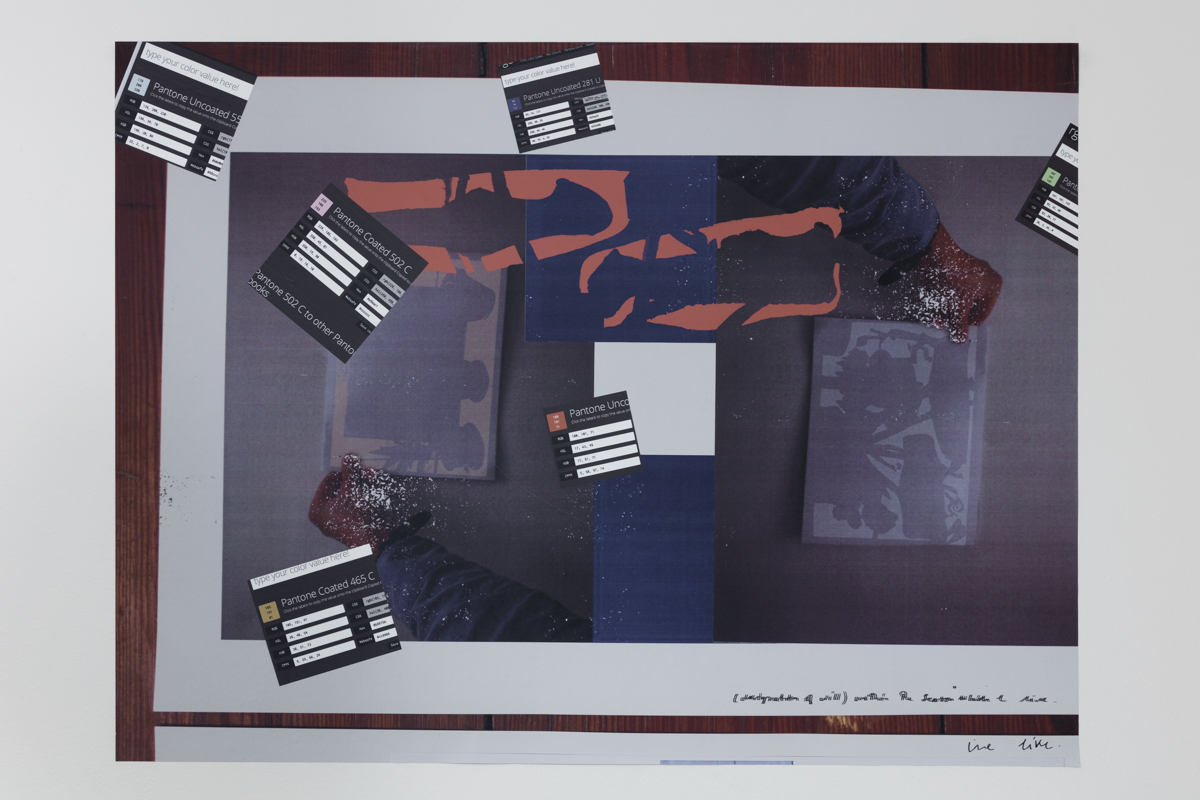

Daniel Malone and Fiona Connor, Vignette #2 (detail), 2016, 35mm slide projector and slides, photocopier, cupboard door, digital print on vinyl sticker, installation view, “Not a Dated Annotation (Designation of Will Within the Season Which We Live),” at Laurel Doody, February 4–21, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Six months before Laurel Doody opened, I invited Daniel to do a show with me. I wanted to do an art-historical show in a domestic context. But the way things happened, it became a two-person show between Daniel and me using art historical material. We used Poland’s avant-garde conceptual history and Los Angeles’s avant-garde conceptual history. Every piece, every vignette, had a reference. It was like a way to digest those places.

I guess all our research was about this basic idea that is a wonderful thing about art history—that objects can be discrete but also embedded within history. And using documentation and research we could try to reattach that context or explore it. Daniel and I developed this show in a very collaborative way. Every piece was collaborative and not singly authored, and that was something important to both of us. One of the main references for the Polish context was a piece that Lawrence Weiner did there, so that made a connection between America and Poland.

Polish artist Edward Krasiński did these shows with this tape that would wrap around the whole space, and then he did them in his apartment and the tape would actually wrap over people. Daniel brought the same blue tape with him from Poland—it’s a particular electrical tape—and this blue tape went over my bed and up to the kitchen cupboard.

Daniel Malone and Fiona Connor, Vignette #3, kitchen cupboard, blue tape, bed, digital print on vinyl sticker, installation view, “Not a Dated Annotation (Designation of Will Within the Season Which We Live),” at Laurel Doody, February 4–21, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

TL: All this seems to present a complex idea of mapping that considers time as well as space; temporal connections are being made, sometime in concert with spatial connections, sometimes not.

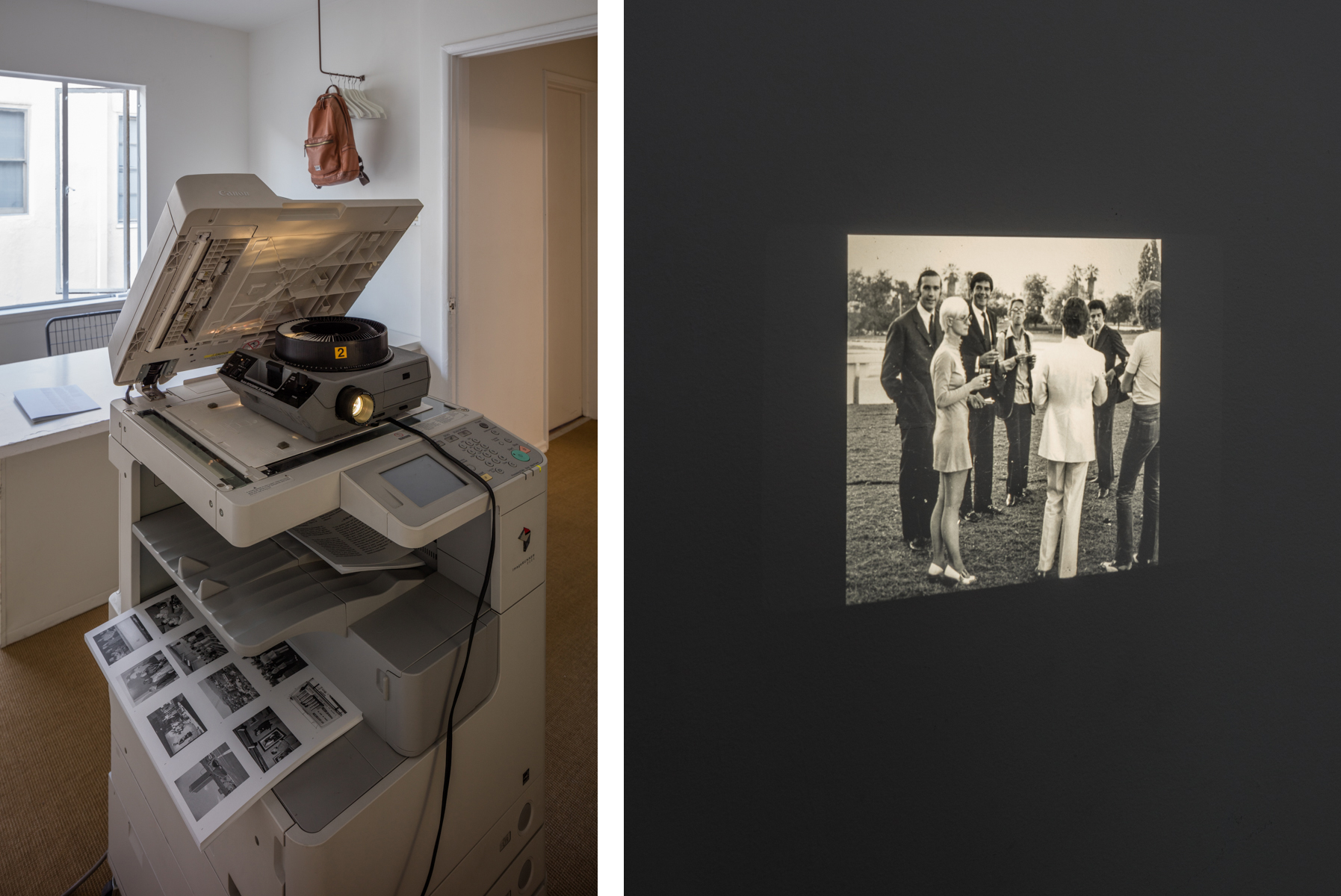

FC: Yes. And to make it more complicated, we had the photocopier producing images by Frank J. Thomas, who photographed a lot of art and goings-on, including a lot of conceptual art, in Los Angeles in the 1960s and ’70s. That was the other referent.

Daniel Malone and Fiona Connor, Vignette #2 (detail), 2016, 35mm slide projector and slides, photocopier, cupboard door, digital print on vinyl sticker, installation view, “Not a Dated Annotation (Designation of Will Within the Season Which We Live) at Laurel Doody, February 4–21, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen. Right: Vignette #2 (detail) with image courtesy of Frank J. Thomas Archives.

TL: It did feel like it had a fairly strong thesis, this idea of connecting: Here are two projects mapping the past avant-garde activities in different locations, and we’re tying them together. It’s an arbitrary tying-together, but then also not so arbitrary because that moment in the counterculture was global.

FC: Yeah.

TL: Am I misremembering, but isn’t that when you were removing the doors and cabinets in relation to something you discovered in the archive?

FC: Yeah, right. The doors were more of a meta thing about archives—the way an item will be put in an archive and become frozen, taken out of use. The front door was taken out of use and put on the wall, frozen. It wasn’t as simple as that, because it created new openings. The kitchen cabinets were shifted and mirrored so they became part of the show, but then highlighted themselves on the other side.

Daniel Malone and Fiona Connor, Vignette #1, 2016, front door, wallwork, digital print on vinyl sticker, installation view, “Not a Dated Annotation (Designation of Will Within the Season Which We Live),” at Laurel Doody, February 4–21, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

The original idea was to take off all the doors and kitchen cabinets and insert them into the walls around the space. Then it became very quickly apparent that was not going to happen because the walls were lath and plaster. [laughs] The front door came off and was embedded in the wall, in the middle of the replica Lawrence Weiner text installation. The cupboard was moved from the kitchen into the main room, and the tape went up over the bed.

You know, every show during that year had a distinct feeling, and with this one I began to feel I was pushing myself out of my own home. I was sleeping under a piece of tape—very different from the feeling with Nick Austin’s show, which was more comforting. That was a suite of drawings, very personal, very conversational; not a forceful argument or thesis.

Nick Austin, Secondary Submarine Studies (diptych), 2015, colored pencil on paper, installation view, “Where Sugar Lives,” at Laurel Doody, December 6, 2015–January 31, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

TL: I think we got out of sequence here—Nick’s show was before the project with Daniel?

FC: Yes.

TL: You re-laid the carpet for Nick’s show?

FC: Right. Re-laid the carpet, put on the skirting, fully cleaned up. I have so much time for his work, because—

TL: He’s someone else you knew from New Zealand?

FC Exactly. He was part of Gambia Castle, the collective as well. The collective really shines through heavily in the Laurel Doody program. What did you think of the show?

TL: I liked it. As you were saying, it was a little bit more of a conventional kind of show than the other ones, which was nice to see because it gave a chance to experience the space as a gallery rather than as a project space. It was interesting to come into the room with that experience in mind and find that it was an exhibition of works on paper.

But it wasn’t just that—because the artist was there, and a cup of tea was made, and a conversation ensued. As you were saying earlier, you set up this experience of hosting; so it was more like a formal studio visit, the kind of experience where you begin to see more the longer you stay and look.

FC: That’s really cool to hear. I guess that’s something that being in a domestic environment encourages, long-durational looking. A lot of the shows were up six to eight weeks, so a lot of people would come back and see them more than once, in different situations—come to the opening, for example, and then come back for a listening party. I really liked the potential for opening up the work to that kind of extended viewing because a lot of the work was new to people, you know?

I think Nick’s work has a sort of righteousness to it that has revealed itself to me with time. He’s persistent and deliberate and that’s something you wouldn’t normally associate with very soft-colored illustrations. He does this thing again and again and again, and, yeah, it’s really righteous.

Nick Austin, installation view, “Where Sugar Lives,” at Laurel Doody, December 6, 2015–January 31, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

What was that piece Zizek wrote about a studio practice being like a very political form of abstaining from a market, having your own space to operate within? I think it was all building on that idea, as was the gallery. I feel there’s a lot of talk and behavior that adheres to the idea that “this is the way it is, and I have to fit within it.” But the gallery was proposing that no, you can really do it how you want it.

TL: The last show was Nicole-Antonia Spagnola and Bedros Yeretzian. It seemed to me that the way it took over the entire apartment was a way of saying that everything had now been covered, explored. That was kind of planned, no?

Nicole-Antonia Spagnola and Bedros Yeretzian, Untitled (detail), 2016, 1 batch/20 bars of soap (organic olive oil, sodium hydroxide and distilled water) eyelet screws, twine, screenprint on vinyl, installation at Laurel Doody, March 13–April 23, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

FC: Yeah, that’s the rogue show. I really respect those two, and when Laurel Doody started, they came over for a meal and just asked me straight-up, “Can we have a show?” I was completely flummoxed, because the program was so pinned down but I had these people in front of me who I respect and would move mountains for. At first I couldn’t see it, but then it made sense, brought the project to a conclusion. They did the final show and occupied the whole space, with bars of handmade soaps hung at regular intervals in every room of the apartment, even the bathroom. Bedros and Nikki’s show was the only show that did this—so yeah, they were using the entire space as a point. I think in some weird way it felt it was pushing me out of the space. It was like the door had been open for a whole year and it was time to leave. Maybe let the building take a breath and move on too.

Nicole-Antonia Spagnola and Bedros Yeretzian, Untitled (detail), 2016, 1 batch/20 bars of soap (organic olive oil, sodium hydroxide and distilled water) eyelet screws, twine, screenprint on vinyl, installation at Laurel Doody, March 13–April 23, 2016, photo: Fredrik Nilsen

Artists have lived in that building for a long time. There was a guy at Liz’s Hardware around the corner who used to live there, and because the landlord’s very stand-offish, that worked out really well. I could do anything I wanted, like change the lighting, change the walls, change the floor. As long as I returned everything “as is.” That worked beautifully, but I had a different relationship with every neighbor. I’m essentially an optimist, so I’m going to start with the good ones.

In the downstairs apartment was a psychoanalyst, and she was awesome and would often just bring up a drink and come to dinners and openings. Same with Jason, who was the hairdresser; I’d give them both a bowl of chili and it was all cool. My other neighbors were also sweet and saw things as reciprocal; they had a baby, and the baby cried at night, so in my head that canceled out any sound we made in the space.

Around the time of Kate’s show, a quarter of the way through, other neighbors moved in, and they really didn’t like the installing and de-installing, moving up and down the stairs, loud noises, people. They verbally went crazy at me, saying all sorts of stuff. Just really crazy shit. But I mean, I did take the door off! [laughs] They got the landlord to call me, and they called the police every time we had an opening.

When the door came off, the police came over. A friend and I were talking in the kitchen and the police came in, and they were like, “We love the show.” And they did selfies in front of the door in the wall. The neighbors were just so pissed because they had called the police to shut it down, not enjoy it.

Bryn Roberts, Dinner Party Series with Laurel Doody, 2015–16

TL: Now that you have moved on, what do you think of the project in retrospect?

FC: Well, I guess a way of answering that would be to say you do what you do, and other people figure out how it works together. Laurel Doody was a pretty savvy operation in some ways. It wasn’t working in a vacuum. A lot of the artists we exhibited were quite established. It wasn’t like we were just fucking around. It was kind of just a bit of everything, a very personal program. It was very personal and all based on hunches. It wasn’t answering to anybody. So in some ways people are like, “oh, it’s just one year-long artwork.” But then it’s not quite that either. I got Fredrik Nilsen to photograph the whole program. He takes absolutely beautiful photographs. And when you’ve got beautiful photographs, the work can travel and it’s powerful. We’re making art here, you know what I mean? I’m doing what feels good, and I don’t need to know how it’s going to work out. But I know it will.