Artists at Work: Wadada Leo Smith

by Anthony Elms

Wadada Leo Smith, 2013, courtesy of California Institute of the Arts, photo: Scott Groller

Wadada Leo Smith (b. 1941, Leland, Mississippi) is a trumpeter and composer. Among other engagements, he taught at the California Institute of Arts until 2013 and is regarded as a respected educator. Any time spent with Wadada makes it clear exactly why: The level of insight and generosity of spirit he exudes are seemingly boundless. He’s long been among the world’s most highly-regarded improvisers, and his compositions have won him numerous accolades. He was a Pulitzer Prize finalist (2013) and a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellow (2009–10); recipient of the MAP Fund Award, Chamber Music America New Works Grant, NEA Recording Grant (all 2010), and Doris Duke Performing Artist Award (2016); and, most recently, received the Mohn Career Achievement Award for his participation in the Hammer Museum’s 2016 Made in L.A. biennial.

Smith has been associated with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) since he became a member of the group in the late 1960s. The organization’s focus on improvisation, composition, mentorship, and self-reliance in equal measure could also characterize Smith, and some of his most storied collaborations—Roscoe Mitchell, Leroy Jenkins, Muhal Richard Abrams, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Davis, and most extensively perhaps, Anthony Braxton—stem from his time in Chicago with the AACM. Smith describes what he makes as creative music, an expansive description of the process, rather than jazz, a limiting and genre-specific term; the at-times chamber feel of his music alongside the broad range of tonal coloration in his compositions, and the instrumental complexity of his ensembles, clearly evidence why he prefers creative music.

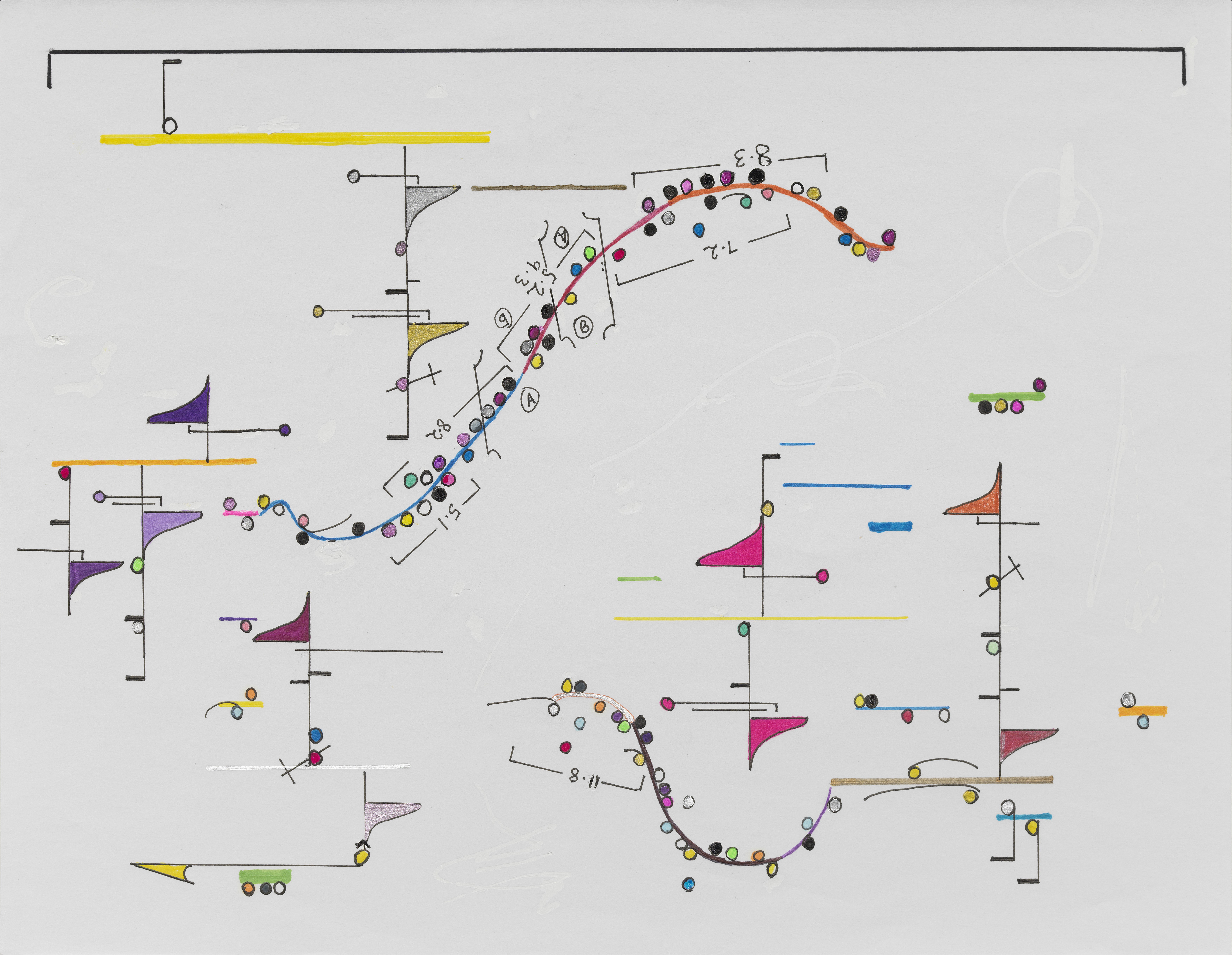

2015 and 2016 have been good years for Smith fans. His long out-of-print self-released 1973 treatise on music, Notes (8 pieces), much discussed among improvisation fans if not widely read, is back in print and as relevant as ever. The book was reprinted in conjunction with the solo exhibition Ankhrasmation: The Language Scores, 1967–2015, organized by curator Hamza Walker and jazz scholar John Corbett for The Renaissance Society in Chicago. Ankhrasmation is Smith’s solution for merging improvisation and composing. The word is a combination of “Ankh,” the Egyptian symbol for life, “Ras,” the Ethiopian word for leader, and “Ma,” a term for mother. Ankhrasmation scores feature traditional notation devices alongside symbolic notations of color and line and space that guide duration and range for the improviser without providing precise melodic lines or tempos. The scores are specific guides that allow improvisers to bring their distinct strengths to the performance of the score. The Ankhrasmation exhibition was included wholesale as Smith’s contribution to the Hammer Museum biennial, alongside a concert with longtime collaborator and bassist John Lindburg. This interview was conducted in June 2016 on the occasion of the biennial.

Anthony Elms: Perhaps we should start with what brought you to the Ankhrasmation scores that were part of the biennial at the Hammer Museum.

Wadada Leo Smith: If we start at the beginning: As a seven- or eight-year-old kid, I was a very good drawer. That’s how I made extra money at my school; I would draw the blackboards for each of the teachers in that school. I got pretty good at it, and then my parents decided that they would put me in some kind of competition where you could get a scholarship to go to school. This is in Mississippi, of course. I must have won the little scholarship, or at least that’s what they said. When the guy came to visit me at the house, he found out that I was black, and they didn’t accept black kids. At that point, I decided that art was not going to be one of the places I would go. After this, over the years, I drew, but only incidentally.

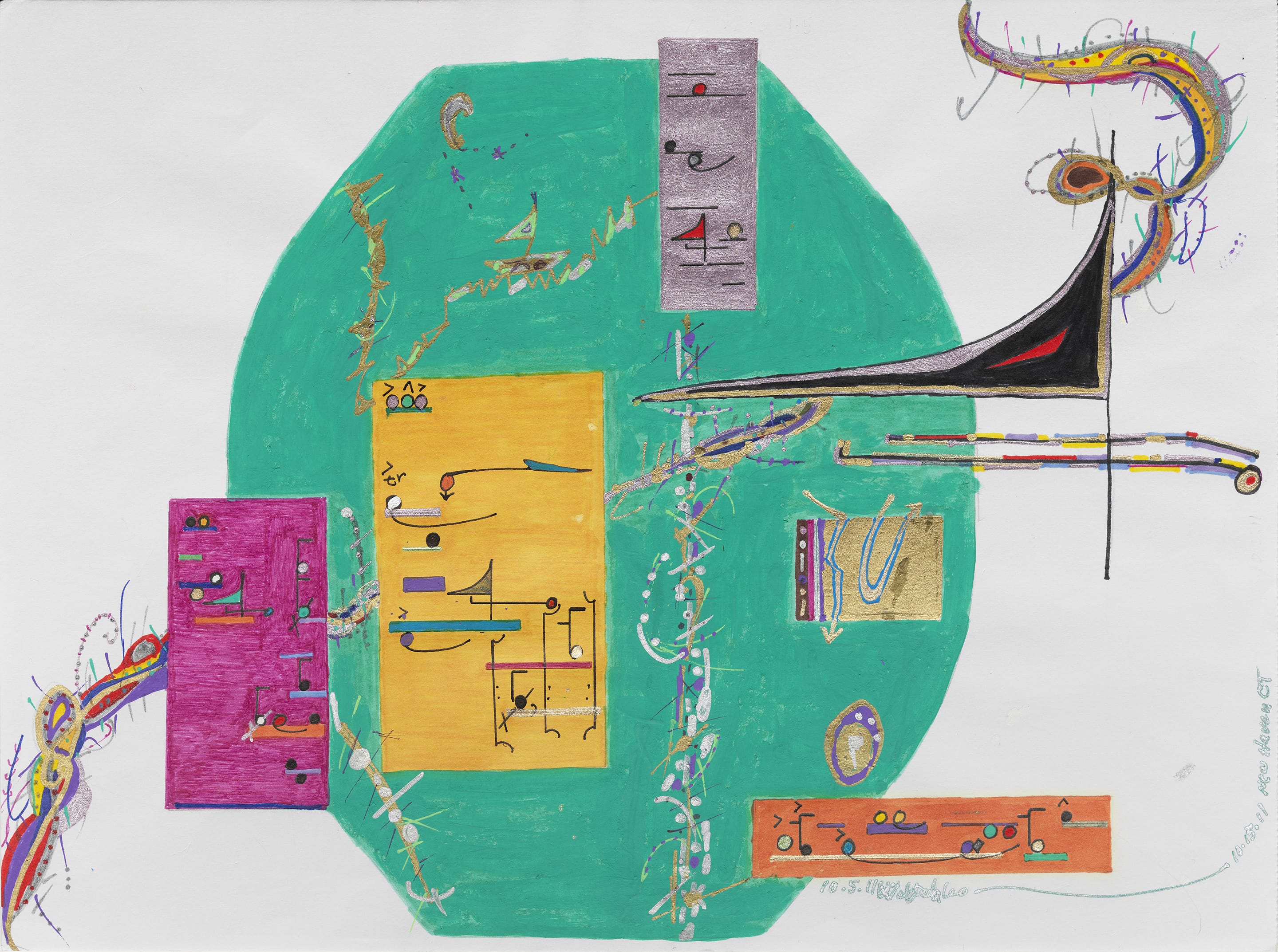

Wadada Leo Smith, Sarhanna, 2011

AE: Wow. So, to backup, you were deterred away from visual arts because of discrimination. Was art something you ever sought to go back to?

WLS: The Ankhrasmation language fulfilled that urge. I’m extremely blessed that I had those formative years of drawing so that I didn’t have to learn how to draw when I developed Ankhrasmation; I just transferred that visual energy that I had into this new expression. And, importantly, I didn’t have to ask anybody to accept this effort except the people in my ensemble.

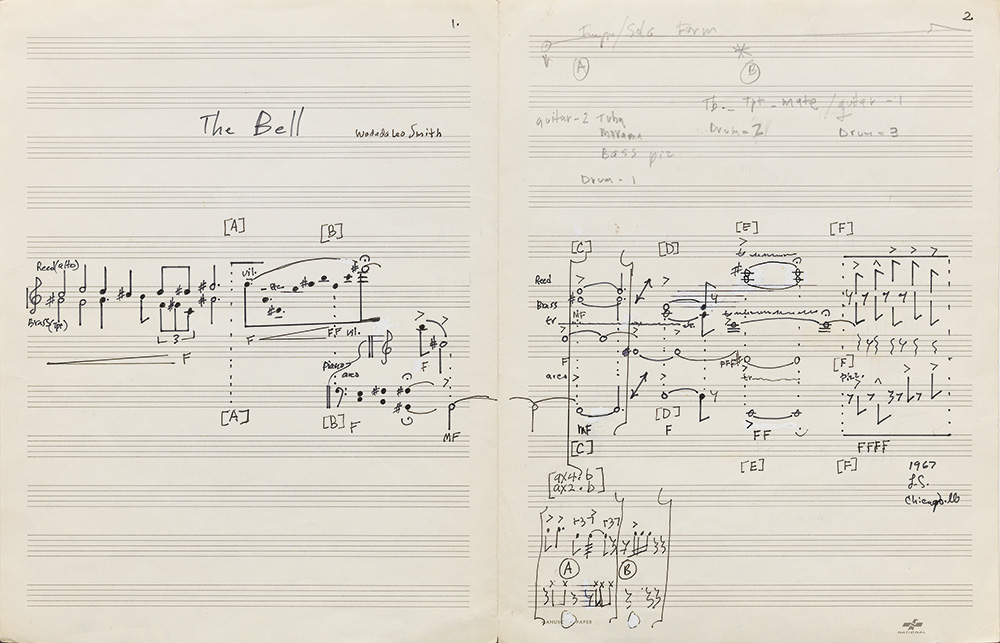

This path opened up for me in 1967, when Anthony Braxton asked me to record “The Bell” for his record 3 Compositions of New Jazz (1968). During recording, each time the ensemble got to a box with a dotted element at the end, there was space. The ensemble finished, yet Muhal Richard Abrams and I kept going. That made me feel that there was a relationship in the markings between the auditory part of a unit, the notes, and the inaudible part, the pause; and here, in this score, I discovered a general idea of how to represent this. At the time, though, I had no idea how to interpret the experience, except by listening back to our recording of “The Bell.” In playback, I discovered how to think about the marks in the dotted box as rhythm units, and that was the beginning. Of course, since then, the rhythm unit language I use has grown pretty large.1

The Bell, 1967

AE: This trajectory is fascinating. Often in conversations of extended techniques for music notation—language, graphic, game commands, etc.—the composer has moved beyond traditional music notation either because it isn’t giving them something, or because they want to dismantle the methods represented by traditional notation. For example, John Cage and his overlayed drawings on acetate, or Cornelius Cardew and his composition “Treatise” (1963–67)—each is a drawing that requires the performers to interpret the variable schematic lines and dots into musical directions. 2In both cases, they are not so much reaching out to the visual to expand traditional notation so much as they are sort of— I don’t want to say falling into the visual, but the visual is not perceived as a developed language with which to extend notation. The visual is only a tool deployed against the perceived hierarchy of traditional music notation.

WLS: Exactly.

AE: What impresses me in your comments is that the visual is an early proclivity you were discouraged from, and when you wanted to expand your musical vocabulary, you already have a background with the visual. It is this toolbox that is already there for you to develop; it’s not about cutting off and beginning again, but rather adding to.

WLS: Right. This is how I explain Ankhrasmation: it must have the formalized structure of composition and the intuitive freshness of improvisation. That language of traditional notation I came out of was not deficient. But as you’re developing as an instrumentalist, you want something more, a way to share more of your feelings with the musicians around you. So you marry these two advanced languages, as opposed to removing or stepping back from one or the other. When both of them are mixed together, like when you mix two colors, they become a new color. That was important for me because the idea of just doing art—for me that is a big problem.

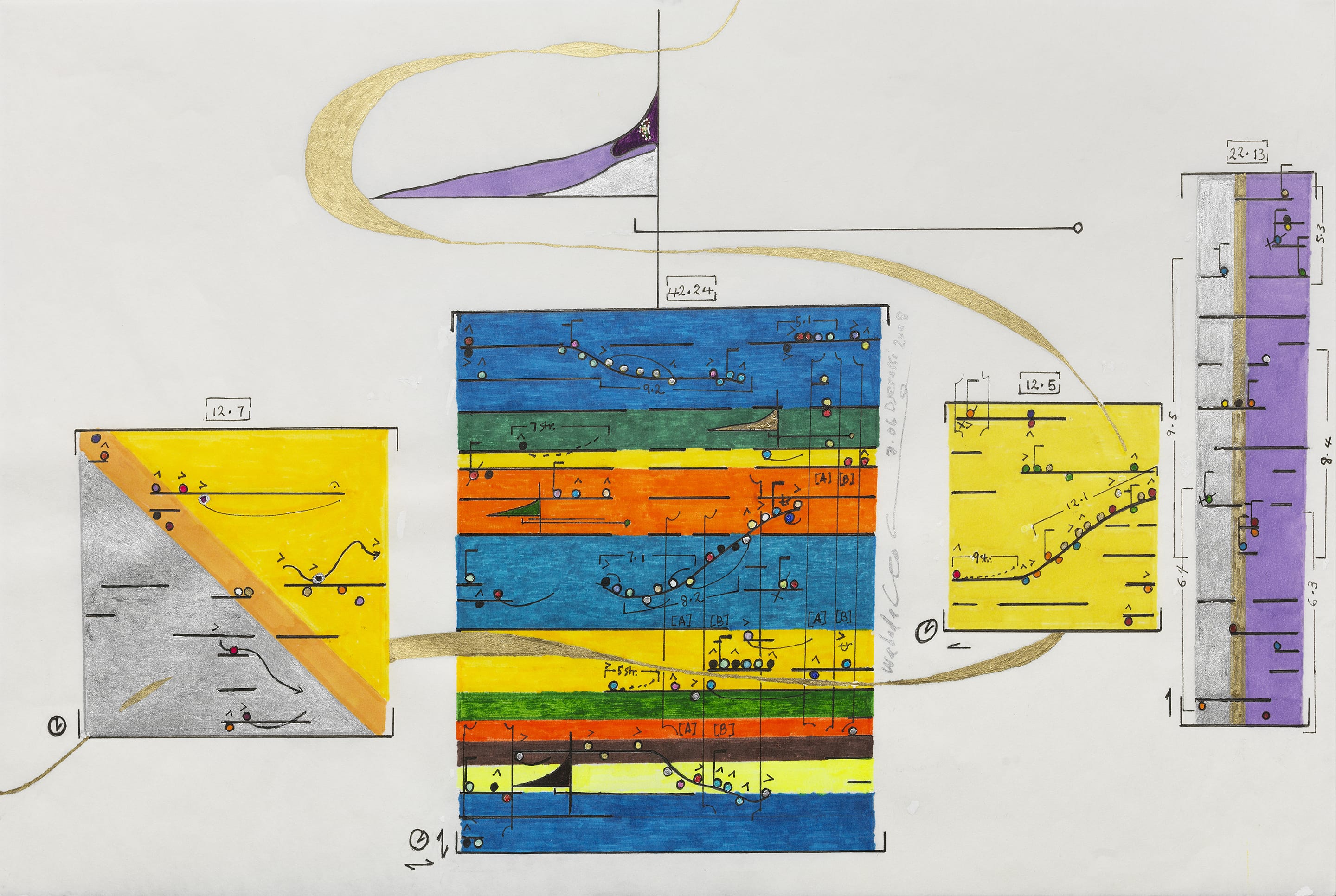

Wadada Leo Smith, Kosmic Music, 2008

AE: When you say art—the visual arts?

WLS: Any art. To me, everything has to be placed in context.

AE: This relationship between formalized structure and intuitive freshness requires memory and having to think through relations. I know you’ve been pretty direct in saying Ankhrasmation scores are not graphic scores—

WLS: They’re not.

AE: So the combination of formal structure and intuitive regeneration—is this why they are not graphic scores?

WLS: That’s one reason. Another reason is because there are rules of engagement and levels of success and failure in my scores. With a graphic score, normally what happens is people play it as a picture; that picture is used as inspiration. With my scores, if they’re used purely as inspiration, it violates the principle because it’s not a picture; it is a score. The rules of engagement for Ankrasmation erase the possibility of someone just using it as a picture to be inspired by, with no level of success or failure.

AE: If I understand correctly, your scores offer symbols that detail proportions—an amount of sound and an amount of silence—and the symbols themselves are crafted to have proportions within and between them. One symbol will tell the performer to suddenly, say, play twice as fast as the last figure, for example. In this way, Ankrasmation does not direct the performer to exact notes or tempos, but to relationships between motifs once a decision has been made. So the relationship between the performance and the score, for a tradition graphic score, is as a one-time reaction—a response, by the performer, to the image that is the score—but it’s a two-way street with your scores. The performer and the score effect each other.

WLS: Exactly. It’s a reaction. In fact, you can actually say that each individual person made that graphic score. Whereas with an Ankhrasmation score, you have to say that I constructed the relationships and the structure, and then everybody made it.

AE: How large of a group has performed an Ankhrasmation score?

WLS: The recorded version of “Occupy the World” (2013) has twenty-three performers and seven pages.3 Normally, I rehearse all seven pages but spontaneously construct it in the performances as I conduct. None of the performers on stage know which page is coming first or last.

AE: It’s a bit of a game piece.

WLS: People use the word game, but I don’t like the word game. With this, you have a controller who’s manipulating the figures that have been rehearsed, and this controller is guiding a composition made in the moment. For me, a game means something a bit different. It means you’re engaged in some play in which one team has something in opposition to another team. It’s a competitive aspect, and it’s not that I think that gaming is bad—

AE: But you do not want competition in this space.

WLS: Not in this space, no.

Installation view, Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only, June 12–August 28, 2016, courtesy of Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, photo: Brian Forrest

AE: How do you prepare people to play the Ankhrasmation scores?

WLS: Normally, I start off by explaining the rhythm units. There are six sets that I commonly use. Actually, today there are seven sets, but I rarely use the seventh set. I made it for potential, but I never teach anybody the seventh set.

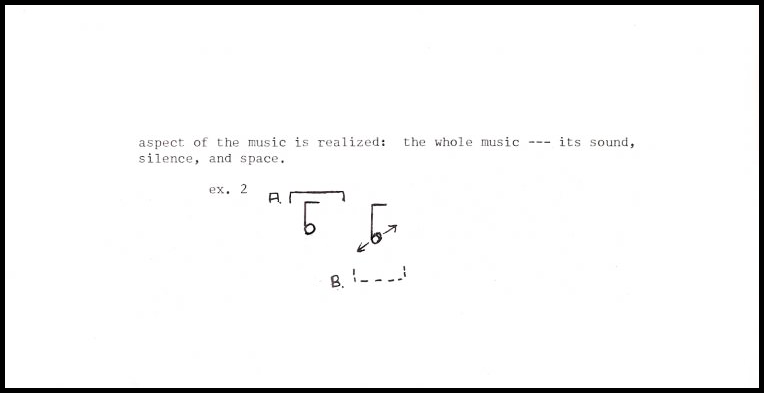

Anyway, I start with the rhythm units because the rhythm units are unique in the sense that they work by proportion. There’s a long portion, and that long portion is called A—when it’s performed or played, it’s an audible portion of that sound. The other half of that sound, which is the inaudible portion, I label B. A and B together makes a complete sound. You need sound and silence to make a complete sound. I’ve been challenged many times on this fact—why is it that you need the audible and the inaudible together, and is that relationship exact? I tell everybody immediately, no, it’s not exact. And the reason it’s not exact is because we’re dealing with proportions and we’re dealing with individual thinkers, and every thinker sees the same proportion, yet how one executes it will be different from person to person. That is exactly what I want.

Proportional rhythm offers the performer the greatest opportunity for the construction of his or her own distinct rhythmic cycles. I explain it like this: Metrical proportions in music bars and time signatures are, of course, precise. But they have a limit. Every metric rhythm is either an odd or even number of beats. Whereas proportion rhythms are only based on long and short. If you try to precisely count proportional rhythms, you’re eliminating individuality and the autonomy of the individual.

Scheme for a rhythm unit

AE: In this turn toward proportions and how to teach them, it seems that you’re speaking to the importance of improvisation and communal dialogue as an ethos and as an ethics, and as a position beyond music. Making decisions as a citizen, within a group of other citizens making their own decisions; not against but with.

WLS: Yes, it’s a social environment. Notation is placed in the perspective of a community. I usually start there, with the rhythm units, because that’s the basis of Ankhrasmation. Those same ideas of proportions are reflected on several hierarchical levels. For example, in one of my scores, when you see a velocity unit and you see different figures inside of it, those insets are also broken down as proportions; and for that I use the term cycles, large cycles and small cycles. Those cycles are spontaneously picked by the performers, and intuitively the proportions begin to construct a musical tower amongst the performers that develops the composition, like a fractal. Can I draw something?

AE: Yes.

WLS: See: set number one, this is A, this is B, and in between that, you have this line, and that makes a whole unit; and in between that, you have an arrow that runs through it, and that makes a whole unit. Within the context of the whole rhythm unit, you’ve got two audible relationships: long and short. As you move on from one rhythm unit set to the next rhythm unit set, which looks like this, this rhythm unit to the next, relationships are developed and built upon.

AE: Because they’re always a pair.

WLS: It’s always a pair. It’s always a pair in the physical, visual sense, but when the players play that one unit, every one of them is being regenerated by the relationship to the others.

AE: It’s from the landscape. It’s around us, it’s from us and it’s from what’s around us.

WLS: Right. Civilization is not various societies having dominance in world power. It’s a single stream where everyone is responsible. It’s those that have passed on, because that material that they laid down made it possible for the next, and the next, and the next. That’s how I think about this stuff. It’s not something that I just sat down and thought about in 1965. I started to think about it because this is the way that I thought as a young kid, and to prove it to myself meant I had to find some answers, and how I found those answers shows something about me.

AE: With this in mind, let’s go back to ’65. I can only imagine there must have been conversations between you and other people invested in these approaches, like Anthony Braxton—

WLS: No, no. Sadly enough, there was no conversation. You know why? I was in the Army. The Army breeds uniformity. It breeds no discontent, and this is poison.

AE: Okay, so let’s not go back to ’65, per se, but how did you arrive in Chicago at the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians)?

WLS: When I went to the AACM, I had a string quartet just about finished. I had ideas, but unexpressed ideas. At the AACM, I met a group of people who were exploring sound and composition, but no one was exploring stuff on a blank sheet of paper. What they were exploring were notions of sound and philosophical ideas about freedom. That’s what I gleaned from them, in addition to a lot of other good things like respect for fear, and respect for the person in the ensemble you play for, and allowing that person to shape the ensemble. I learned how to be strong on the stage.

Jazz musician and composer Muhal Richard Abrams stands in front of the stage as he conducts the AACM Big Band (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians), Chicago, IL, ca.1965. (Photo by Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images)

One of the original AACM members, Muhal Richard Abrams, had a big band—I don’t use that phrase, “big band,” but he does—and in rehearsal he would select a bunch of guys and maybe ask you to play. Then once you start playing, the others would all walk off stage and leave you there playing, and then they would stand on the side of the stage, just beyond the curtains, and they would talk. You could hear them talking while you’re playing. They’d do that to see what you are and if you could become part of the group. Out there playing, you discover a lot about yourself and about them—a lot! In that one moment, you just grew up.

AE: But how did you get to the AACM?

WLS: I met a guy in my last Army post in Colorado. This guy had been in the military, in Korea, with Anthony Braxton. He gave me Anthony’s telephone number. When I got to Chicago, I called Anthony up. He says come over. I go over to his house and carry with me an edition of scores edited by John Lewis and Gunther Schuller, I believe. Anthony and I, on our first meeting, spend a couple hours playing this book, just this book. Nothing else.

AE: This fellow, did he think, “I know Braxton. You should meet.” Like this is someone you need to know?

WLS: Yes, because those last few months in the Army, I’m reading bits and pieces here and there in Downbeat and other magazines about the AACM.

AE: So, you were aware of the organization?

WLS: Yes, and my wife’s family lived in Chicago. I had a lot of family there too. The main goal after the Army was to go to Chicago, where there was something happening. Get there and play with Braxton. At our meeting Braxton says clearly, “I will introduce you in the AACM. You’ve got to become part of the AACM.” Braxton, when he says that, he absolutely means it, but it evaporates. He just forgot.

Maybe a week or two later, I’m walking in my neighborhood, the Old Town area of Chicago, and I see a sign that says Joseph Jarman and his quartet are playing in this coffee house. Now, I know the name Jarman.

AE: From those little blurbs in Downbeat?

WLS: Yes. So I said, “I’m going to go there.” I went really early, and when I got outside the coffee house, Lester Bowie and Roscoe Mitchell had just ridden up on their motorbikes—they had leather jackets on, they had high boots on. Lester Bowie had a cigar that long [exaggerates with hands], and Roscoe was looking like a rebel.

AE: As he often did those days.

WLS: They were in jeans and open clothing, meaning nothing was buttoned. They looked just like rebels. I went over. They got off their bikes and they said, “Hello,” and I said, “Hello,” and we started talking. Roscoe says there’s a rehearsal on Monday night. This was like a Friday night. He says, “Come on Monday. Muhal has a big band that rehearses every Monday night—go there and bring your horn.” He gave me the address. It was on Cottage Grove Avenue.

Smith (left) with Roscoe Mitchell

AE: Going back to a statement you said as a tangent a bit ago, you said you never use the term “big band.”

WLS: Right. You know why?

AE: Why?

WLS: Because Duke Ellington called his ensemble an orchestra. Fletcher Henderson called it an orchestra. Jelly Roll Morton called them orchestras. Benny Goodman called it an orchestra. Paul Whiteman called it an orchestra. The whole tradition of orchestra is always there, and these big band guys— I don’t know what state they came from, but somehow they came in, and I believe that the notion of big band is associated with arranging.

AE: An arranger is reworking someone else’s material, rather than composing.

WLS: An arranger’s not a composer. I don’t use the words “big band.” They always did.

AE: So, back to your introduction to AACM.

WLS: Right. So Roscoe also said to come to the AACM on the Saturday after the Monday rehearsal and he would introduce me to the group. That Monday night, I go. I leave my horn in my car trunk. I meet Muhal as I come in, and he says, “Well, go sit down and take a listen.” Very rough, like, “Go sit down and take a listen.” I go sit down and I take a listen. All the guys looked like rebels and outsiders—really hip guys. They start rehearsing, and the trumpet players—there were three or four of them— don’t play the figure right, and Muhal’s getting more and more angry. Not swearing angry, just “Come on, guys. It goes…” You know.

AE: “Get it together.”

WLS: Right. And all of a sudden, in his frustration, he turns around in the rehearsal and says, “Hey, you got your horn? Go get it. Come play this phrase.” I walk out, get my horn, come up, sit down, play the phrase. The whole band turns around to see who this new guy is. It was an instant kind of connection from everybody. That next Saturday I go to the AACM meeting, and Roscoe Mitchell stands up and introduces me, and puts my name in to become a member of the AACM. That’s a long story, but that’s what life is about. These beautiful narratives.

AE: Within the AACM, I identify both you and Braxton as the primary leaders in trying to find ways of scoring beyond traditional notation. Not at the same level, but you’re the ones that I think of as having the earliest, most distinctive approaches.

WLS: Yes, but we found different ways.

Wadada Leo Smith, Vision, from Kosmic Music, n.d., courtesy of the artist and Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago

AE: You and Braxton never discussed his work with diagrams—appealing to scientific notations and formulas—relative to your investigations with symbols and rhythm units? I mean, you both have written nearly contemporaneous extensive texts on your methods.

WLS: No, no, no, no. His and mine are very different. His are more realistic, mine are symbolic. Look at the LP of his that’s called Saxophone Improvisations Series F. He has a diagram of stuff in there, and for notes that go up, he uses a step. A step going up, or undulating line going up, is an ascending pattern, et cetera. That’s a realistic thing that’s part of our environment. Mine are symbolic shapes, so any portion of it can be interpreted by the individual if they have learned the language. They can actually add to the language.

AE: If the interpreter can add to the language, they need to study it, obviously. What are rehearsals of your scores like?

WLS: Ankhrasmation scores don’t necessarily need to be rehearsed. But if you’ve got a group of people who show some kind of difficulty or conflict, then you do this kind of thing that we call a rehearsal; but you don’t really have to do it. The ultimate goal when I write an Ankhrasmation is to have a score that can be played instantly by a group of players who have even just a small portion of the language down.

To that effect, at CalArts with a guy named Mark Trayle, who’s an excellent electronic composer, we created this design for an ensemble—the Creative Music Electronic Ensemble—that ran for fourteen years at CalArts. Two years on, one year off. The reason we did that is that we wanted to affect the climate of people coming into it. Once they’ve gone in for two years, people come back into it just to check it out, and that’s not the same as what you come into it for. We wanted to erase those people, put a year between, and maybe get a new breed of people who actually want to learn something new.

Every class would be self-sufficient. It would start out and I would draw a rhythm unit, draw a velocity unit, and then I would construct that in a music tower with an improvisation symbol; and those three properties, they would learn them that same day. In the last 35 to 40 minutes of the class—it’s a two-hour class—we would play, and then we would quickly self-critique by going around to everybody in the ensemble and having them present what they did in the piece, what the difficulties were, and what was successful. Then the full ensemble would determine what was successful and what needed to be corrected. When they walked out of that first class, the students had three symbols that they could visually identify and they had played through those three symbols. Every class was run like that, so we got a fresh performance of the language right away.

Smith and students at CalArts, 2009, courtesy of California Institute of the Arts, photo: Scott Groller

AE: It sounds like rehearsal is less about learning the score and more about—

WLS: Learning the symbols.

AE: And also learning the personalities within. Learning how to be part of a social system.

WLS: How to be part of a social dynamic, but also the velocity unit, the rhythm unit, the improvisation unit—you can’t learn all of it in four or five or six years. You have to grow with it and begin to experiment with your growth.

AE: Another question I want to ask: There’s a sort of retrospective moment happening with you right now. The scores are on display. Notes has been republished. Is looking back something you’ve always had within your process, or is this a different feeling for you now?

WLS: I don’t see that as looking back. I see it as continuing. I made those scores starting in 1967 and up through this year—some of them I play, some of them I put on the shelf—and I simply pull them off the shelf and bring them out. I know what you mean. You mean that these things are happening now and when I look it over, what do I see? I see this: I see that from the very beginning when I was twelve years old, I saw something and I still see it now. The people that realize their own destiny don’t need to be measured by other people.

Notes (8 Pieces)

That idea was crystallized for me through Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations. He was both emperor and a spiritual leader, and people called him a philosopher. He was a mystic. I read that when I was twelve years old.

AE: That’s kind of early to read Marcus Aurelius.

WLS: I read it because in those days I read these magazines; they’d give you five books if you signed up and paid three or four dollars. I didn’t know who Marcus Aurelius was. I didn’t know what meditation was. I bought it and then I perused it and began to read it, and here were some fundamental principles about spirituality and the relationship of the human being.

About this same time, I started playing the trumpet. Approximately three months from my thirteenth birthday—like September, October—I wrote my first piece, for three trumpets. At that time, I had not committed to memory the framing for all the notes, but I did know that there were twelve notes, and I put all twelve of them in the score. I went and got my friends. Sammy T. Scott, Cleo Hall, and me, we sat down in the gymnasium and we started rehearsing my score. We played it and my band director, his name was O’Neal Jones, he came downstairs and said, “What are you guys doing?” You know what I said? “We’re playing a piece of music I wrote.” He says, “Hold it.” He goes upstairs—he played clarinet and alto saxophone—and he got the alto saxophone, and he came down and played one of the trumpet parts on the alto saxophone. He didn’t transpose, he just played it as is. So there I am. I hear this sound that I’m going to hear for the rest of my life because I don’t transpose for instruments either. That’s why my sound, if I’ve got five instruments or ten, it sounds twice the size, because every instrument has not been reduced to C, what they call the concert key.

Wadada Leo Smith, 2009, courtesy of California Institute of the Arts, photo: Scott Groller

There’s no such thing as a concert key. That’s a political position. The French horn is in F. The alto flute is in G. The trumpet’s in B flat, but also it has B flat, E flat, D, F, G, A, you see. Each tonality in those twelve tonalities, once they’re sounded, present a sonic spectrum. That sonic spectrum is unique to itself, and if you mix these sonic tone spectrums—let’s say with a B flat and an E flat, and an F instrument—you have three spectrums existing at once, but only if you don’t transpose. If you transpose, you make a French horn sound artificially in C, and you make a B flat trumpet sound artificially in C, and those three instruments produce only one spectrum. That rich spectrum is the dynamic we lose in music dominated by this idea of concert pitch.

AE: This keeps circling back. I’ve said it before, and you’ve said it before, and we both said it earlier: This is not just an argument about instruments. This is an argument about how people are, how people can be.

WLS: The whole gamut of socialization, if you want to look at it like that.

AE: This is a way of being in the world with differences.

WLS: Yes, because art making, frankly, is so vital—just like, for example, doctors and sanitary workers. All of us have a specific function that makes the society whole and complete; and the fact that we are on stage is incidental, because the stage itself doesn’t make the music. That’s just a place, a place that has made itself a dominant part, but it doesn’t make the music.

AE: In Notes you assert that the artist must be self-conscious, and it’s most important for the black artist to be self-conscious. Do you still find yourself to be self-conscious?

WLS: I find myself realizing that I was right in 1970, when Notes was published. Everything in there. Even if I could not have known that. You see, the radical views and direction that people take always happens in their young years, but you can also be a radical in your late years.

This notion of awareness is an important political aspect for human beings and the communities in which they live in. In America, just like in the world, the idea of otherness and difference is still the weakest component of society. It is less valued. It’s less recognized. My proclamation for self-consciousness, my intention was to say to this community at large—African, European, or whatever—that one should be thoroughly aware of what’s going on in this world that we live in. Being aware means you have a glimpse of how you stand in the political and social and economic spectrum of our society. That’s still true today. That doesn’t change.

AE: Back about twenty years now I saw an interview with Roscoe Mitchell in Chicago. He was asked about the performers he loved and why. This conversation was around the time he was restaging his important ’70s compositions “L-R-G” and “The Maze” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. You are the L in “L-R-G.” Instead of saying he liked your playing, or your attack, your tone—common things said of horn players—he said, basically, “I like how Wadada breathes.”

WLS: I never heard that, and I’m extremely joyful to hear that, because he’s a master of art making and for him to say that, that’s beautiful. From his perspective and from mine, that’s a good explanation of it. It eliminates all the foreground.

AE: It’s acknowledges your reason behind the rhythm and velocity units. To have proportions, fast and slow; tone and pause make a total sound. It brings that duality and balance into a statement on how you perform. It tacitly acknowledges the drive behind Ankhrasmation scores: To have the space accompanying any statement considered as important as the statement. Obviously, he’s listening to something which is at your core. Your breath.

WLS: Breathing shapes the size of the sound, the timbre of the sound, the kind of texture it’s going to have. It would take a book to fantastically write about that.