Beyond the Muscle

by Kate Wolf

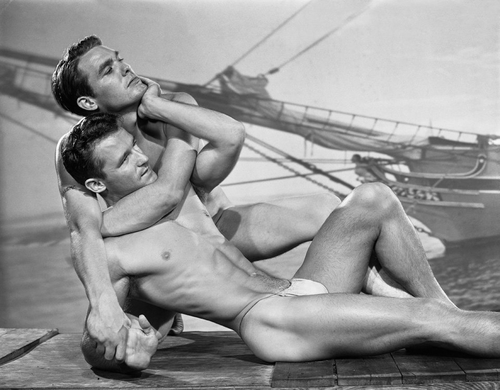

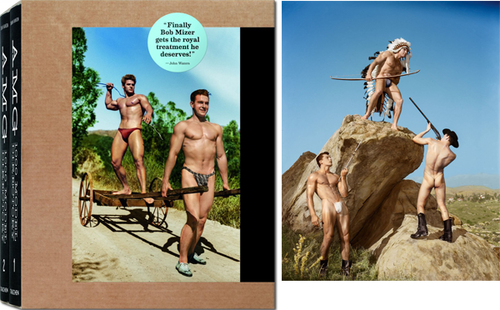

Fred Hare and John Kemble, 1951 © The Bob Mizer Foundation, Inc.

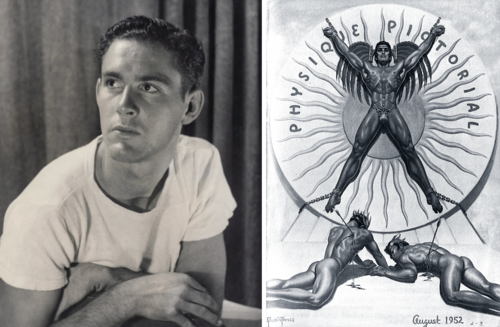

Robert (Bob) Henry Mizer was among last century’s most prolific photographers and, in writing about him, it’s hard to begin with anything other than the sheer volume of his output. Under the mantle of the Athletic Model Guild (AMG), a photography studio that he operated out of his home and a small empire of surrounding properties in the Pico-Union neighborhood of Los Angeles, Mizer photographed around ten thousand models over the course of almost fifty years. He made over three thousand films and nearly as many videos, and published his images in Physique Pictorial, the landmark “beefcake” quarterly he wrote, designed, and edited from 1951 until two years before his death in 1992. A precursor to the hardcore pornography and the radical underground presses that erupted after Stonewall, Physique Pictorial was initially produced under the guise of an art and fitness journal. It is now considered to be one of the first, if not the very first of its kind: a widely distributed magazine that celebrated the male form for its aesthetic pleasures, and whose intended audience was gay men.

Mizer’s photographs—playful, mysterious, intimate, campy; “a hothouse hybrid” of styles, in the words of critic Vince Aletti, in which the “subject wasn’t mere musculature but masculinity itself”— are narrowly focused, but they contain multitudes.1 His models (who appeared mostly in posing straps—essentially G-strings—or with their genitalia otherwise cleverly concealed, until censorship laws eased at the end of the 1960s) ranged from former Mr. Americas and fitness pioneers to bodybuilders-turned-actors, like Arnold Schwarzenegger. A teenage Joe Dallesandro sat for Mizer before going on to fame as an Andy Warhol superstar, and the contemporary artist Jack Pierson modeled for him in the late ’80s after showing up at AMG one day.2 In large part, though, the people he photographed were anonymous. They posed in return for copies of their pictures, for the sake of the stardom they hoped to one day achieve, for the flattery, and for the relatively easy money—originally, five dollars for two and half hours of work at a time when minimum wage was seventy-five cents. Their bios, which Mizer prided for their authenticity, document a full spectrum of postwar working life: in addition to the aspiring athletes and performers, there were firemen, truck drivers, carpenters, ministers, office clerks, factory laborers, sailors, marines, street hustlers, fry-cooks, lumberjacks, minor criminals, and college professors.

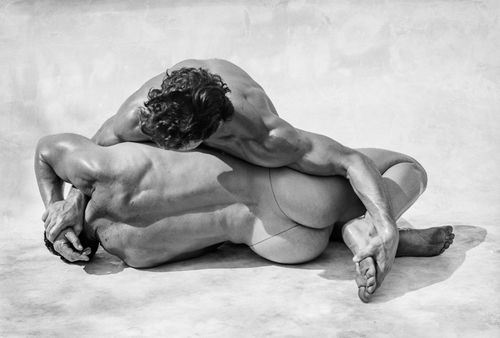

In photographs these men enter into a realm of domesticity that was only semi-fictional, since many of them actually lived at the AMG compound at some point. Smiling, they lather themselves in Mizer’s tile shower, lounge by the swimming pool he built on his property, rifle through his refrigerator, or roughhouse together. Sometimes they appear out in the elements, at the beach or in the desert, but more often they pose on the alpine sets Mizer constructed with papier-mâché rocks, Astroturf, and dead Christmas trees on his office roof. In lustrous glamour shots, models are pictured against the patterned, light-filled backdrops Mizer achieved by placing pieces of crystal on an overhead projector set behind a sheet. Still other backdrops, costumes, props, and animals—such as goats, dogs, monkeys, roosters, kittens, geese, and donkeys (many of them Mizer’s own pets)— evoke a panoply of kitschy and wild handmade worlds, and mythical characters: cowboys, aliens, bikers, Roman gladiators, military generals, naughty fauns, sexy wizards, African warriors, gun-toting bandits. Harnessed to madcap plots, such characters also encounter one another in Mizer’s films: a paracinematic oeuvre extraordinaire, predominately improvised and executed with the guileless immediacy of erotically charged home movies in which most conflict invariably resolves in some form of spontaneous, almost-nude wrestling.3

The majority of this work is now maintained in an archive in Northern California. The archive’s owner, Dennis Bell, classifies it—perhaps accurately, considering Mizer’s prodigiousness—as the largest collection of photographs by any single photographer in the world; the archive’s holdings include an estimated two million images, or about one-seventh of the Library of Congress’s entire photography collection. For much of last year, I corresponded with Bell for an article about Mizer in which I also charted the story of Bell’s acquisition of the Mizer estate. Part of this was out of necessity, since the archive is not yet open to the public; but I also became interested in the roundabout path that had led Bell—who used to work as a photographer and filmmaker, like Mizer, but mainly in the porn industry—to devote himself to the life’s work of a man he’d never met. I was surprised to learn that the collection had flown low enough under the radar that before Bell purchased it in 2003, it was being offered by an old associate of Mizer’s, Wayne Stanley, for a relatively modest sum on Ebay.

Stanley seems to have been an especially careless steward, but it’s not as if the Smithsonian was knocking down his door, either. Like the work of most artists in commercial and sexually explicit genres, the place of Mizer’s work in the larger culture was marginal until only recently. First it was threatened by censorship and prejudice; then, after the emergence of hardcore porn, by obsolescence; and later, after his death, by neglect.4 Though ever the budget collectors item, for many years Mizer’s images hung in a balance, mostly absent from consideration within an art context, and under recognized despite its value, as I will argue, as a groundbreaking part of free speech and LGBT history.

Even now, as his photographs appear increasingly in gallery shows and in major exhibitions at places like The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA), and New York University’s 80WSE Gallery, Mizer’s legacy still seems half-written and in the process being formed. And legacy building, as it turns out, is a tricky business, discussed in a way more often given to unalloyed stories of artistic martyrs and their selfless champions, rather than those in which everyone’s motivations are complicated and varied.

In many ways, AMG recalls the wonderful title of Thomas Schatz’s book on old Hollywood, The Genius of the System. Mizer was a studio executive and inspired director in one; he mixed a regimented pursuit of commerce with nimble skill and deft creativity. In making its claim for his legacy as an artist, Mizer’s estate, understandably, has deemphasized the commercial aspect of his work. They also shied away from discussing the various external factors that may have influenced its preservation, such as the shifting of both the art and porn market. I’d hoped to write more about this in particular because, as archives go, the story of the conservation of Mizer’s work is unique (it was, for instance, funded in part by the production of eighteen original porn films) and it deserves recognition. But the resistance of the estate to talk candidly about money only seems indicative of a larger tension inherent in repositioning Mizer within the fine art world. On the estate’s website, which highlights his more idiosyncratic photographs, Mizer is portrayed not as a vintage pornographer, but as an unsung artist and iconoclast. Of course, he was both.

Left: Bob Mizer ca. 1945. Right: Cover of Physique Pictorial, August 1952 © The Bob Mizer Foundation, Inc.

For his part, it seems Mizer was never apologetic about making money in a genre he helped create. He regularly polled readers of Physique Pictorial about the kinds of images they wanted to see, and AMG was almost always profitable. By many accounts Mizer was frugal—his deep suntan, old clothes, and straightforward manner made him easily mistakable for a farmer—and he was a shrewd businessman. He started his company with two other partners, in 1945, as referral service for models; by 1947, his partners had left and through the sale of his pictures alone he was able to support his mother, Delia, and his brother, Joe. Business, he once said, “grew like topsy.”5

Even had his business not worked out, though, there’s little indication Mizer would have ever wanted to do anything else. He worked nonstop, seven days a week, and led an ascetic lifestyle. He developed gout at thirty, which accounted for his vegetarian diet, and he didn’t drink, smoke, or do drugs. But he was open to outsiders and to some degree re-created the boarding-house atmosphere in which he had grown up; he started hosting models at his home as early as 1948. Unlike other physique photographers, Mizer included his real address, not a PO box, in his magazine. This meant customers and prospective models could locate him easily but so, too, could police. At the time, the Comstock Law, passed in 1873 at the behest of zealous anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock, barred the sale of lewd material, including nude photographs, through the US mail; in California, the law also made it a crime to possess such photos, even of oneself. Mizer had been taking nudes since the early days of AMG but he had been discreet about distributing them, and he never published them. But in a climate where local authorities were openly hostile to anyone suspected of being homosexual, his enterprise was conspicuous. Mizer’s first conviction came in 1947 and it landed him in a California prison work camp for an entire year.6

Bob McCune and Herb Lamm, 1949 © The Bob Mizer Foundation, Inc.

In 1954, shortly after Los Angeles newspaper columnist Paul Coates ran a smear campaign in the Los Angeles Mirror calling Physique Pictorial “thinly veiled pornography” and claiming its audience was “among the most brutal, horrifying sex criminal—the sadist,” Mizer’s studio was raided and he was arrested for the possession and intended sale of indecent material.7 He was sentenced to a two-month jail term. The arresting officer—the sole witness—exhibited nudes along with posing-strap photos at the trial; but it was disputed whether or not these had actually been taken by Mizer, or had even been in his possession to begin with. After an appeal in which Mizer’s lawyer cited the interpretive and evolving nature of obscenity, the conviction was overturned to little fanfare (thus setting no legal precedent) the next year. But from this point on, as he later recalled, Mizer felt he needed to be “cleaner than Caesar’s wife!”8

He still found ways to incite. In 1963, Mizer began to classify the models in the pages of Physique Pictorial by adding a set of symbols he’d devised from astrology. He referred to this as “Subjective Character Analysis” and eventually offered to provide curious readers with a key that was two-tiered: The public chart indicated that the various tiny squiggles next to a model meant that he was a “TYPICAL MAN,” “Closed minded,” and “Strongly religious” or “Aggressive. Enthusiastic” and “Very affable.”9 But a decoder uncovered after Mizer’s death shows the signs also denoted explicit information about the models’ sexual preferences and willingness to perform or receive sexual acts (along with unsparing commentary about things like the models’ intelligence and whether or not they were worth the trouble of photographing). Although it’s unclear if Mizer ever distributed this list, its simultaneous logging of both erotic and professional matters seems a good indicator of his protocol at AMG. According to various confidants, sex (often paid) with models was common; but whether someone was a good at posing—“a photographer’s dream,” as one of the private symbols notes—was equally, if not more, important.10 “Shooting models was an even bigger compulsion than sex,” Mizer’s friend, the photographer David Hurles, told Taschen editor Dian Hanson for her book Bob’s World, “so he always photographed them before.”11

While hardly scientific, Mizer’s habit of recording the sexual inclinations and practices of his models, consistently and over the decades, in many ways mimics the work of someone like Alfred Kinsey, with whom Mizer and several other physique photographers corresponded. Art historian Thomas Waugh writes that Mizer was emboldened after reading Kinsey’s 1948 study, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, in which Kinsey famously found that 37 percent of men had had homosexual experiences leading to orgasm at least once. As he told Waugh, the effect of Kinsey’s book on Mizer was “like taking a ton of chains off.”12 Kinsey’s findings appeared at a time when the American Psychiatric Association still classified homosexuality as a mental illness; when, under the newly minted Miller Sexual Psychopath Law—originally instated to fight child molestation—anti-sodomy rules were being enforced more strictly than ever; and when, in the so-called “Lavender Scare,” the State Department was beginning to take steps to purge the US government of all federal employees believed to be gay, under the auspices that, like Communism, homosexuality was a disease capable of infecting others and carried with it a major security risk.13 Kinsey’s study contradicted this type of paranoid demonization; it found that homosexual activity was not a sexual perversion but was, in fact, common and statistically normal.

Galvanized by Kinsey and radicalized by his time in prison and many run-ins with police, Mizer became a politically impassioned commentator. In the pages of Physique Pictorial, he railed against the hypocrisy of censorship and, beneath the photographs of sweet-faced, smiling young men, reported on his own legal travails, as well as those of colleagues like Richard Roscoe (who was indicted in 1957 for selling “aesthetic nude prints” by mail, and fined so heavily that he needed to sell even more nudes to compensate) and Al Urban (whose third trial in New York City, in 1960—for the postal sale of the same Classical-style nude that had cleared a special sessions court just four years before—sent him to jail and ultimately ended his decades-long career). Mizer encouraged readers to get in touch with the American Civil Liberties Union and called for tolerance in this editorial from 1956 titled “HOMOSEXUALITY AND BODYBUILDING”:

What difference does it make if a bodybuilder is Catholic or Protestant, etc., white or black, Republican or Democrat, homosexual or heterosexual, —isn’t the physical culture program as suitable for one as for the other. Indeed, human nature being what is, we can never find ourselves in complete agreement with every detail of behaviour [sic], social and religious mores etc., so let us consider only what we have in common with one another and not seek to erect unnecessary barriers. And before attempting to condemn others for their particular “sins” which we do not share in, let us attend to putting our life in exemplary order.14

In closing, he advises readers interested in further information to send away for literature from ONE Inc., publishers of ONE Magazine, the first pro-homosexual magazine in the United States, founded in Los Angeles in 1953, and later an educational institute; and the Mattachine Review, the publication arm of the Mattachine Society, founded in Los Angeles in 1951 by Harry Hay and regarded as the seminal gay-rights organization of the United States.

The connection between these early advocacy groups and photographers like Mizer runs even deeper than it may first appear. Historians such as Waugh and David K. Johnson have made eloquent cases for the central role of physique entrepreneurs in the nascent fight for gay rights. Johnson suggests that “it was the very rise of a gay consumer market that helped provide the rhetoric and construct networks that fostered gay political activism.” Magazines and mail-order businesses such as Mizer’s “provided a means for gay men to understand themselves as belonging to a larger community.”15

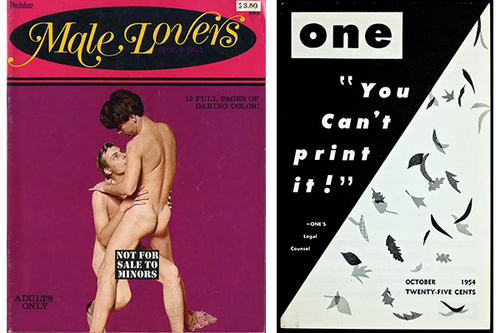

Left: Male Lovers. Right: ONE Magazine, courtesy of ONE Archives at the USC Libraries.

In 1954, the publishers of ONE Magazine also found themselves charged by L.A.’s postmaster for obscenity, if only for the magazine’s open depiction of gay themes; a kiss between two women in one published short story was especially controversial. But when the case arrived before the Supreme Court in 1958, the guilty verdicts of two prior obscenity trials were reversed. The Court cited a ruling from the previous year’s case against Samuel Roth—a publisher and pirater of literary works and esoteric erotica who was tried and jailed for the postal sale of his risqué magazine, American Aphrodite—in which it was determined that to classify as obscene a work must, as a whole, appeal to the average man’s “prurient interest.” The Roth case helped establish that sex and obscenity were not necessarily synonymous. Going a step further, ONE’s exoneration implied that homosexual content alone did not invariably make a work obscene.

A mounting number of other victories followed. In 1962, the frequently convicted Herman Lynn Womack, DC-based publisher of physique magazines Grecian Guild, MANual, and Trim, brought suit against the US Post Office for seizing hundreds of his publications and labeling them lewd; it went to the Supreme Court and he won. Without condoning the content or the intended audience of Womack’s magazines, members of the Court reasoned that his materials were no more objectionable than “many portrayals of the female nude which society tolerates.”16 Almost exactly five year later, in Minneapolis, an even greater coup occurred when a federal case was brought against DSI, a highly profitable mail-order business distributing everything from national directories of gay bars to greeting cards, records, and films, including some films of Mizer’s; DSI also published the magazines Butch and Tiger, which, starting in 1965, featured frontal nudes. After US Marshals raided its warehouse, DSI’s two owners faced 145 years in prison if convicted. Unexpectedly, the presiding judge found both defendants not guilty on all twenty-nine charges. The judge stated that DSI’s magazines where within the limits of decency upheld by contemporary society; pivotally, he also acknowledged the magazines’ audience as a gay consumer group entitled to the same rights as any other minority group. Mizer wrote about the verdict, heartened but still skeptical: “From our point of view, the waters are as muddy as ever and there do not exist any clear guidelines.”17 But the floodgates now seemed open, for both the impending gay rights revolution and the hardcore porn that would soon reign in the seventies.

After years of crusading for the freedom to publish what he wanted, Mizer shifted his concerns after the DSI verdict to the oversaturated market. “DOES OVER-SATIATION [sic] DESTROY A TASTE ALOGETHER?” he asks in his January 1970 issue. “MANY FIRMS GO BANKRUPT.”18 While his work had thrived under constraint and small production costs because of his continual inventiveness and an obsessive shooting schedule that enabled him to select only the most evocative photographs, many new publications dispensed with this type of artfulness and artifice, and instead plainly depicted sex. Though Physique Pictorial went nude in 1969, it remained a handmade magazine with a cover price of just one dollar; it was now competing with an influx of more expensive, color publications like Male Lovers and Gaystuds.

When sales started to dip for the first time in the early seventies, Mizer briefly ventured into making XXX features and loops (shorts) for other companies, but hardcore just wasn’t his thing. (He claimed to have a personal “anathema” to looking at ejaculate and used Tame shampoo as a replacement.)19 Despite the relative chastity of Mizer’s later work, though—naked wrestling, spanking, light S&M, ass shots, kissing, and petting are featured, but little else—AMG stayed in business for the next twenty years. By the end, the majority of its income came from videos of Mizer’s photo shoots, notable for his embrace of the Warholian ideal of letting the camera roll with minimal interference. (Gore Vidal was supposedly a fan of the sessions where guys really gave Mizer “bite” or where they just seemed “incalculably stupid.”)20 Without the frisson of censors, Mizer’s later writing in Physique Pictorial focused on recounting the misdeeds of his models. Tales of arrest, theft, drug addiction, and general waywardness abound, undercutting the lasciviousness of the pictures in a strange and at times darkly humorous way. One typical caption, from 1984, appears beside a nude model, Brian Diaz, who thrusts his pelvis forward and leers into the camera: “Found him selling TVs at a swap meet in Arcadia, Ca. As you can see, he is high on pot (of which we disapprove,) but were we to wait until he was completely straight, the pictures might not have been done at all.”21

In 1989, Mizer’s health faltered and began to slow him down. He’d developed kidney disease and needed to have dialysis three times a week, though he scheduled his appointments early enough to still allow nearly a full day in the studio. Sitting and standing became painful, so he photographed lying down on a kind of sled he’d made for himself. His last photo shoot took place about a month before he went into the hospital to await a kidney transplant. He died there before the operation could take place, on May 12, 1992, at age seventy.

These days, despite his recent turns in museums, Mizer is best known to art history for being the inspiration of another artist. In the sixties, David Hockney based a number of paintings off photographs from Physique Pictorial and credits the magazine with making him want to move to Los Angeles. “I was quite thrilled by the place,” he writes of visiting AMG when he did. “I bought a lot of… photographs… which I still have.”22 Robert Mapplethorpe, of course, appropriated physique material and used it in collages like Bull’s Eye (1970), and the now deceased L.A. painter Tony Greene gessoed Mizer’s images directly onto his canvases.23 Warhol must also have been aware of Mizer’s work beyond the fact that they shared Joe Dallesandro as a muse.

Jack Pierson, Tomorrow’s Man 3, artwork courtesy Richard Tinkler, design courtesy Bywater Bros, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Mizer’s influence has been noted, but his work, and physique photography in general, still seems to be given most currency in passing, as a source of reference—something akin to the ubiquitous mention of advertising’s impact on pop art. A truly in-depth study of Mizer’s photographs and films has yet to be published, and much of the existent literature (which is often marred by misinformation) occludes an analysis of the work on its own terms: its formal techniques, aesthetic patterns, sociological insight.24 Not unlike the documentarians Walker Evans and August Sander, Mizer captured a substantial portion of a mostly working-class, postwar population with a uniquely honed vision and style. His work is both a register of a hermetic world, a fantastic fiction, and also a kind of testament. As Vince Aletti writes:

We have proof: All these men took their clothes off in downtown Los Angeles over the last half-century. Some of them wrestled, some of them hugged, some of them showered with a friend; some wore nothing but cowboy hats, others put their heads in stocks and their dicks in chains. Why? Why not?25

“He could take these boys from the street,” says Dian Hanson, whose second book of Mizer’s photographs was published by Taschen this fall, “and photograph them so they looked as if they were staring up into the face of God. He was able to get this sort of angelic awe out of them.” “Of course,” she adds, “[Mizer’s friend] John Sonsini has said that this look you often see on their faces, when they’re kind of gazing upwards with this breathless look, was achieved because Bob had mounted a mirror over the chair that he sat in to photograph them. They were looking up at themselves.”26

Left: Bob Mizer, AMG: 1000 Model Directory, courtesy of TASCHEN. Right: Joe Leitel, Steve Wengryn, and Don Fuller, 1957 © The Bob Mizer Foundation, Inc.

Perhaps as Mizer becomes more recognized as an artist, one who helped pave the way for sexual freedom, a brighter light will be shed on other physique practitioners as well. Though they were both visionary and exceedingly prolific, it’s probably not a complete coincidence that Mizer and Physique Pictorial contributor Tom of Finland—who started his own foundation for his meticulous, boldly sexual comic drawing with his close friend and business partner Durk Dehner in 1984—are the most visible of the era. Mizer and Tom of Finland are unique in that their legacies have benefitted tremendously from individuals who seem driven by some productive, ineffable mixture of self-interest and devotion, who’ve been willing to do the painstaking work of archiving and promoting without sizeable institutional or financial support. But as the artist Richard Hawkins, who co-curated an exhibition of work by Mizer and Tom of Finland at MOCA in 2014, told me: “One look in the storage facilities of the Tom of Finland Foundation, the ONE Archives in Los Angeles, or The Leather Archives in Chicago will tell you that’s just the tip of the iceberg.”

There’s even room for discovery within Mizer’s own archive, which Bell is still processing with the help of interns. While putting together Mizer’s show at the 80WSE Gallery a few years ago, Bell and the artist Billy Miller, with whom Bell used to collaborate, discovered a stash of early studio and documentary work Mizer made around Los Angeles. Like a Nathanael West novel, the pictures show the peculiar off-gassing effect of Hollywood on the city’s inhabitants. Exhibitionism and fantasy are everywhere: the men, women, and kid bodybuilders posing at Muscle Beach in Santa Monica; a scene of a magician hovering over a woman floating on water; a headshot of the actor Tyrone Power peeking out of a wooden door frame, dressed as Zorro. Even the Siamese cat Mizer captures laying on a velvet settee seems to be vamping for the camera. Bell told me there are thousands of examples of this kind of imagery, most of which Mizer never printed during his lifetime.

The buildings that housed Mizer’s beefcake empire in Pico-Union still stand today. Two years ago, the Office of Historic Preservation in Los Angeles cited one of them—1834 East 11th Street, Mizer’s former home—as a significant place for LGBT history in the city, making the address an easier sell for landmark status. Bell also recently announced that Mizer’s archive will be moving to a brick-and-mortar space in San Francisco, which heralds the possibility of a future research facility open to the public. Mizer himself may never have anticipated that kind of attention, or that his photographs would be hanging in museums, but he did believe in the greater significance of the work he was doing. “New physique titles are sprouting up like mushrooms,” he wrote in 1963. “This frightens the antagonists who in times past have been able so successfully to suppress this group and write them off for cranks. But this group will not be suppressed…they have tasted a little freedom and now they want full recognition and will settle for nothing less…Only at a future time, possibly many years hence, will the tremendous and vital sociological importance of the movement created by these books be fully realized.”