Artists at Work: Hayley Barker

by Sóla Saar Agustsson

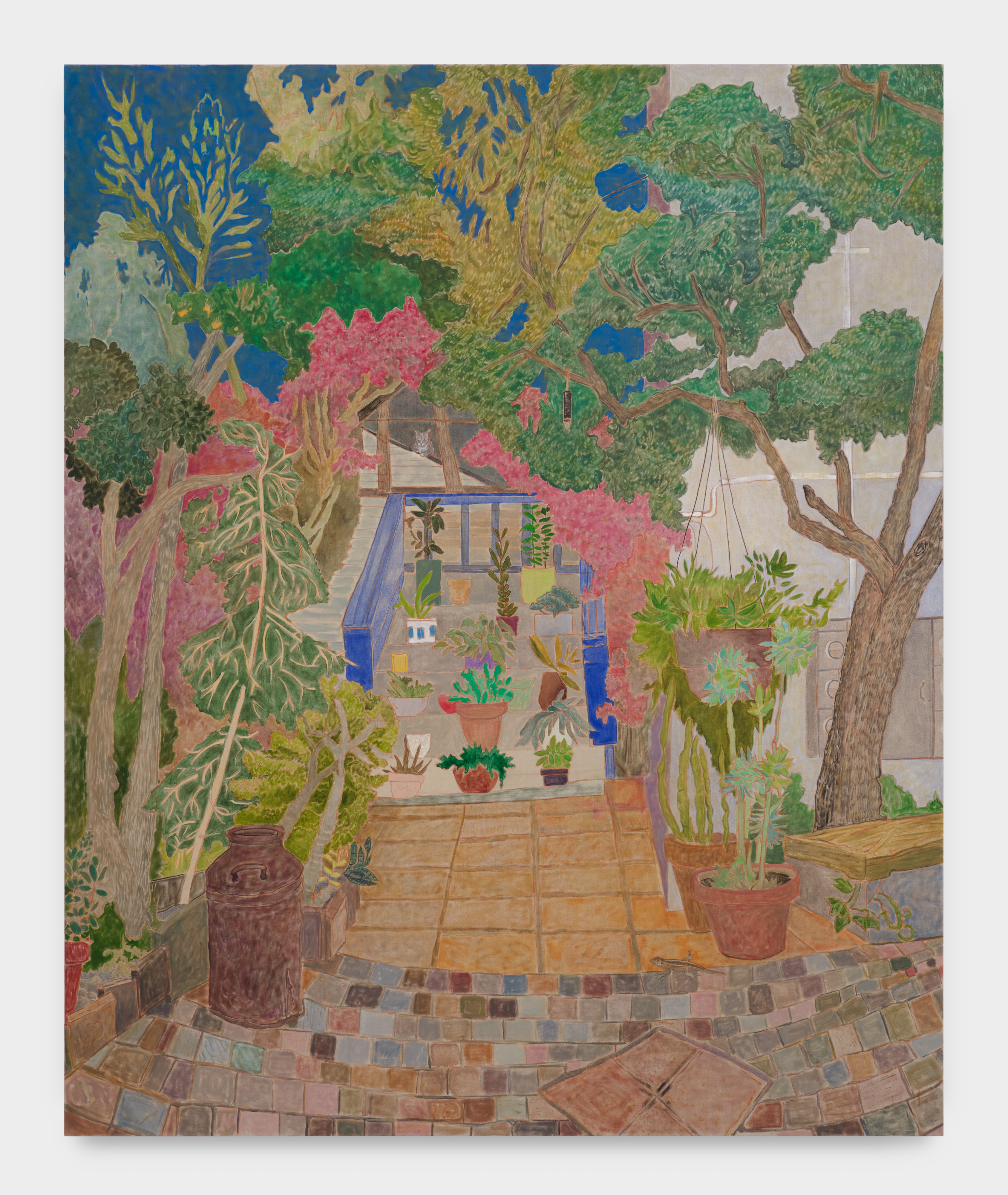

Hayley Barker, The Terrace Path, 2023, oil on linen, 100 x 82 in. (254 x 208.3 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

Hayley Barker’s paintings depict landscapes of gardens and homes she visits and inhabits, works which render the texture and movement of the natural world as something that is not only seen, but lived in. Influenced by tarot and earth-based spirituality, her early practice as a performance artist, and feminist artists such as Ana Mendieta who incorporate their embodied experience into the natural world, Barker’s work offers a fresh perspective in contemporary landscape painting.

Born in Oregon and based in Los Angeles, Barker received her BA from the University of Oregon (1996) and her MA & MFA in Intermedia from the University of Iowa (2001). Her work is collected in the Brooklyn Museum, Columbus Museum of Art, High Museum in Atlanta, and University of Iowa Museum of Art, and has been shown at SHRINE in New York and Los Angeles, Night Gallery, Bozo Mag, The Armory Show, Art Basel, and elsewhere. Laguna Castle, her solo exhibition at Night Gallery in February 2023, arose from an artist residency established in honor of Isa-Kae Meksin, a community leader, activist, former public school teacher, and long-time resident of Laguna Castle, a historic apartment complex in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. Barker drew largely on photographs of Meksin’s lived-in spaces and the complex’s lush communal garden, depicting intimate landscapes built upon community-based credos led by Meksin, including shared purchases, sliding scale rental agreements, and political gatherings. I recently spoke with Hayley about the evolution of her artistic and spiritual practice, and her time at Laguna Castle in Echo Park.

Sóla Saar Agustsson: I wanted to start by asking you about your beginnings as an artist… How did you first decide to start making art?

Hayley Barker: I was always interested in painting and drawing and collage, and when I was a kid I loved singing, acting, dancing, all of it. But really, I decided in undergrad to study art, and I took a lot of drawing classes and some performance classes, even though they didn’t offer many when I was in school. But the students fought for it, so we were able to take some performance classes that were just one-on-one independent studies. I feel like that was really when I started taking art seriously—when I was advocating for what I wanted in my education. But I always was drawing on my own, and I started playing around with oil paints after my dad gave me some when I was in high school.

SSA: I read that you enrolled in the MFA program at the University of Iowa partly because you felt drawn to the work of Ana Mendieta. Can you speak about that?

HB: One of my professors had studied at Iowa, and this was back in the nineties when we didn’t have as many resources for finding out about different schools, so connecting with your professors was a great way. But one of my art professors had studied with Hans Breder, who Ana Mendieta had also studied with. Hans passed away a few years ago and he was an artist in his own right, and he ended up being Ana Mendieta’s boyfriend for a while and sometimes her collaborator. So anyway, I applied to go to Iowa to follow in her footsteps because I had learned of her work through this professor of mine, and I ended up studying in the same department and with the same person that she studied with [Breder].

SSA: Were there any works of Mendieta’s in particular that influenced your work?

HB: The Silueta series was the first work of hers that I was exposed to. They showed me that [an artist’s] work can be relatable and at the same time can contain dichotomies and mysteries. She enacts the desire to be born of the soil and to be subsumed, buried. Her body’s impression is the shape of an ancient goddess. It’s a memorial and a celebration. A spring morning birth and a funeral hole in the ground. It contains everything I need in a work of art. I think of the goddess as being present in all my paintings. Or maybe I am making a space for her to appear.

SSA: In an interview for Juxtapoz, you mentioned that your early performance work was influenced by Riot Grrrl and artists Kathy Acker and Diamanda Galas. What were your early performance pieces like, and do they relate in any way to your current practice?

HB: My early performance art was very much inspired by Mendieta and also by the feminist punk shows and books of that cultural moment in time in the Pacific Northwest. So, they were DIY, text-based, poetic, and sometimes included music and earth. At the time I was also healing through some trauma, so those artists offered cathartic experiences that taught me how to express and move through rage and grief. I wouldn’t say that they directly relate to my current work, but without them I never would have gotten through some of the toughest times of my young adulthood.

Hayley Barker, Still Angry, 2020, oil on linen, 25 x 20 in. Image courtesy Night Gallery and the artist.

SSA: What made you transition from performance art to painting?

HB: Well, I feel like I always did them in tandem, but it was after grad school. I had been doing a lot of video at that point in lieu of live performance and I had a studio visit with a local curator—this was when I was living in Portland, Oregon—and he noticed a bunch of my drawings on the side, and he was like, “do you ever show these?” I said no, I don’t, no one sees these! But then I thought, ok, interesting, people might actually care about these things. So, I started allowing myself to draw more and it ended up taking all of my attention.

At the same time, I have to say that a very practical reason I switched was because, when I first got to Portland, I was doing a job at a call center where I was on the phone and on the computer all day long. When I got home I just didn’t want to be on my computer or editing video or anything like that. I just wanted to be doing something way more visceral. So, it was a practical consideration, but it became the premier thing I wanted to do at that point.

Hayley Barker, Riverwood 2, 2021, oil on linen, 100 x 82 in. Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist.

SSA: You’ve described yourself as an “earth-based intersectional feminist witch,” which I love, and you’ve mentioned that tarot and witchcraft are central practices in your personal life. Do you still practice those things?

HB: I do. I’ve been doing tarot reading since I was 19 or something, so that’s been a solid 30 years or so. And that’s accompanied me through life as well as collecting rocks and crystals—I’ve got a lot of rocks, even from when I was a child. I came to describe myself as a witch when I was living in Portland and I was with a coven that called it “earth-based spirituality.” During undergrad I read a lot of books that had to do with reawakening the Gaia cult. A lot of them were written by scholars who were questioning sexist interpretations of archeology and very early goddess sculptures. So, it goes way back for me and I still practice it today. I still celebrate seasons and try to engage in intentional actions around the moon cycles and cross-quarter days, and I indulge in some plant magic. I have a little garden and I’m interested in the ways that the earth is our body and we are the earth’s body. It’s been called “ecofeminism” in the past, but really what it comes down to for me is just caring for the earth, and the rejection of misogyny, racism, ableism, sizeism, the destruction of the planet, homophobia, and of course capitalism—everything that hurts the planet—and trying to nudge ourselves and our intentions towards that which grows along with the planet.

SSA: Your work navigates emotional ties with the landscape. Do current ecological crises have an impact on your relationship to your work, which is so directly related to the natural environment?

HB: Yes, the current ecological crises directly impact my feelings about the earth. I feel great sadness every single day for the way we have destroyed our environment. I am in mourning and rage over it.

As a painter with the opportunity to share the work I make, I feel a great sense of responsibility and acknowledge that I have a great deal of privilege. I get to shine a light on what is important to me: our relationship to the earth on an intimate scale. I pray that my paintings can help inspire care and love for nature exactly how she shows up for us in our daily lives. Maybe this change in perspective can be a small step towards a love that encompasses the earth. I also garden and am learning how to do so in a way that incorporates native plants. This is an action I can take every day to try to undo a tiny part of the damage we have done.

Hayley Barker, Incense (Riverwood 4), 2021, oil on linen, 100 x 82 in. Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist.

SSA: Do you meditate or participate in other spiritual practices? I know that painting, especially when centered around nature and landscape, can be meditative in a way, and that seems parallel with your philosophy.

HB: I’ve meditated at various points in my life, though I don’t do sitting meditation these days. This is something I’ve really struggled with. I’ve gone through so many phases with this and sometimes beat myself up for not sitting and meditating, but other times I also think that to “still your mind” is such a weirdly patriarchal way to describe what meditation is. Why does the mind have to be still? Why can’t the mind be a wave and foamy? Why can’t it be something soft and still hold focus?

All that is to say, I’m not good at meditating and I don’t really like it, but I do love focusing on painting for hours at a time. And when you do it full-time, the way that I do and that I am grateful to be able to do, it is my meditation. The amount of focus I have to bring to making work is really a lot. I never thought I’d be able to work this much and I also didn’t know it would take so much out of me. So, it’s a real dance between this focus towards this task that’s unfolding and at the same time holding the energy gently enough that you don’t overdo it in some way, whether that’s in the way you’re painting or in the way you’re moving forward in your day. It’s such a balancing act, so it’s a moving meditation.

SSA: That’s interesting because usually meditation is described as clearing your mind, but is that even really healthy?… Do you have a ritual or routine when you paint?

HB: I paint five days a week. I tend to work really early and paint in the morning. I get up around 4 a.m. most days, just naturally, and I get to the studio as soon as I can and work until the early afternoon, then I take a nap, and then I go home and have the rest of my quiet day, that’s my jam. In terms of the ritual of painting, I always have two cups of coffee before I get up, and then I write a bit. And sometimes I’ll have one song I put on—that’s my dance song. I’ll dance to a song or two prior to engaging in painting. It’s very ritualistic.

Hayley Barker, My Folk’s Place, 2023, oil on linen, 144 x 100 in. (365.8 x 254 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

Hayley Barker, My Folk’s Place, 2023, oil on linen, 144 x 100 in. (365.8 x 254 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

SSA: Your dad was a writer and your parents were progressive, perhaps bohemian. What was that upbringing like?

HB: My dad’s still a writer. He writes Lovecraftian fiction and poetry and horror. Having my dad be such an active daily writer, and my mom being such an avid reader, they both just brought so much curiosity and creativity into every day of my childhood, and that was such a great focus. I loved that if I just wanted to read all day, it was encouraged as a good thing. There wasn’t pressure to do so either; it’s just what we did. We just read all day sometimes, or we made collages.

My dad always had art materials on hand, and he makes pretty cool paintings himself. So it was great to have those resources, and I feel really lucky to have grown up with that richness. They still live in Oregon, and they’re progressive and had a hippie background coming from Long Beach and then moving to Oregon, so it was an interesting childhood.

We didn’t always have a lot of money, but my parents were always dragging me to museums. My mom does have a lot of “get up and go” energy. She’d always want to go somewhere and explore something on the weekends, so we would go to natural history museums or art museums. When we lived in Long Beach we’d go to LACMA, or we’d just go see whatever was out there in the world to see. That’s probably why I somewhat naively still think museums are really magical because as long as they’re not charging admission it’s a pretty great way for folks of all economic brackets to have a glimpse at something outside their sphere. I know I’m idealistic in lots of ways, but it’s still sometimes true.

SSA: Earlier this year you exhibited some of your paintings in your show Laguna Castle at Night Gallery. The paintings were described to me by the gallerist as “Proustian,” which got me thinking, because they’re very textural and they obviously depict natural environments and landscapes. Does sensory input, like smells or textures, influence your paintings?

HB: I think perhaps I have some synesthesia. Most of my memories of places are associated with a color or a smell or a sound or a rhythm. I always think of landscapes as having different smells, and that’s probably from this sensory experience that I have, but also from growing up in Oregon where the landscape could be so incredibly lush and at times the sense of it is very strong. You walk out into a field after being in the forest and you’re on the side of a mountain and you’re surrounded by wildflowers—that experience is so visceral and I feel like I still carry that sense with me and I still experience it even when I do so many paintings just in my yard. I still experience that if I, say, wake up in the middle of the night or at 3 a.m. and have to go look at the moon. I know this sounds corny, but it’s this weird thing that happens from time to time—I wake up and have to go outside for a minute and just look. The smell of the world at that hour is very different depending on the season, and all these things—the moon, the time, the weather, the plant life, or if skunks are out, and all the heat, or the cold, the smells, the lushness, or the lack of water—all these things become such a visceral ball of feelings for me, and I’m sure for many folks. But that experience absolutely feeds how I think about landscape; it’s about being in it, not just looking at it.

Hayley Barker, Front Yard at Dusk with Visitor, 2020, oil on linen, 82 × 100″. Image courtesy of SHRINE, New York and the artist.

SSA: So, what’s it like to paint spaces that you physically inhabit? Because I know the paintings included in Laguna Castle came out of the artist residency that you did at the Laguna Castle apartment complex in Echo Park, formerly inhabited by Isa-Kae Meksin.

HB: I didn’t inhabit Laguna Castle for very long, but I have visited a number of times and I have a strong sense of that place from those short visits and from the folks I know that live there. I think maybe not knowing that landscape as well as I know some of the others I’ve painted allowed me to bring the narrative of that space more to the forefront… But it always came back to this wondering: how do the folks who live here in this space inhabit this world of Laguna Castle? And how might they do so at different times of day, or in different seasons? And if you wanted to go read a book out here, where’s a spot you might want to put a little blanket down and bring some lemonade and just read for a bit? Where’s a good spot to fit your body in? Stuff like that.

Hayley Barker, View from Isa’s Window, 2022, oil on linen, 80 x 65 in (203.2 x 165.1 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

Laguna Castle, Hayley Barker, installation view, Night Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, 2023. Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Marten Elder

SSA: That’s interesting because early Western painting was very much about not inhabiting the landscape. It was more about capturing the natural world from a colonialist perspective and less about enjoying it with your body in a more holistic sense.

HB: At least in Western painting, for sure.

SSA: The Transcendental Painting Group—painters working in New Mexico in the late 1930s and early ‘40s, like Emil Bistram and Agnes Pelton—was also influenced by spirituality and nature. Has any of that work influenced your own?

HB: I’m not an expert on it by any means, but I have loved Agnes Pelton for a long time. I learned of her work almost accidentally about 20 years ago, and I was lucky enough to see her show at the Whitney. I think her work is incredible and part of what I love about it is that it reminds me of the origins of what would come to be called New Age spirituality, and the art of those folks. While New Age spirituality included a lot of misguided cultural appropriation, I have to admit that aspects of that movement, that era, shaped how I see and understand the world. I have a real soft spot for that art because I love this somewhat naïve universality of spirit that comes into some of the worldviews that would’ve been called New Age when New Age was forming in the 1970s. I also love the way Pelton’s work is that of an American painter’s way of processing and interpreting ideas from Eastern mysticism. I find that to be pretty interesting, but I also can’t relate to it in a lot of ways. I love it formally, and I love the colors and the sci-fi energy of that work, but I also don’t entirely relate to all the spaciness and the airiness. And I don’t mean to say that with derision, but the art I want to make isn’t quite so cosmic and it’s a little more earthy; it’s a little more Ana Mendieta making her shape into the soil and a little less straight lines in this abstract space.

SSA: You’re quoted in a review of your work in Artforum that “enjoying beauty and flowers seems more radical to me.” What drew you to start centering your art around natural landscapes?

HB: Well, I think it was a number of things, but partly it was a way of bringing some of my early performative leanings into a two-dimensional process. A lot of my early performance work had to do with nature and moving through spaces, and I used to do a lot of plein air drawing, which I’d then make paintings from. I was showing these in Portland for five or six years and to me it was always about that relationship of embodiment and co-creation with nature, and ways of describing how the architecture of nature is the perfect architecture for the human body.

At the same time, in a more emotional way, I think painters like Charles Burchfield had a really big influence on me when I was growing up. I found a book of his at the library when I was younger and just about stole it, I loved it so much. I always think about how emotive his landscapes are and how they show so much of the state of his spirituality and his soul. That, to me, felt like a very freeing way of making work that was simultaneously about emotional or psychological states and exploring states as places at the same time. So, it felt like a way of showing how that line between self and nature is way fuzzier than what we like to pretend it is.

The Spider, Hayley Barker and Shari Urquhart, installation view, SHRINE, New York, NY, 2022.

SSA: Definitely. So, you don’t paint from drawing anymore, you paint from photographs?

HB: I do. I take a lot of photographs of the places I’m either living at or looking into. It’s a long process and I wish I wasn’t so slow at it, but it takes a really long time to find the right photo or make the right photo to paint from. But maybe it will get easier someday, maybe not; maybe that’s part of the process, that it’s hard, but it’s also a way of getting to know the landscape for me.

SSA: Your work from your residency at the Laguna Castle reveals intimate glimpses into the life of Isa-Kae Meksin, who was a long-time resident there and who passed away in 2022. Your paintings Isa’s Necklaces (2022) and Isa’s Wall of Photographs (2022) especially reflect this intimacy. What was it like inhabiting her space and former apartment where many of her possessions remained?

HB: Honestly, the first night I was there and staying in her bedroom, it felt a little too close and almost disrespectful; I was scared to be in her bed. But the second night I felt totally comfortable and welcomed and really enjoyed learning about her through her possessions, through her books and photographs and clippings and saved objects from travels and gifts from friends. I feel like I got to know her on this intimate level and that was quite beautiful and really unfolded over the times I stayed there. I feel honored to have been able to spend that time with her.

Hayley Barker, Isa’s Necklaces, 2022 oil on linen , 43 x 31 in. (109.2 x 78.7 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

SSA: Isa-Kae was a well-known community organizer and activist, particularly for LGBTQ and housing rights, and that apartment complex maintains a really close-knit community. Did any of this influence you and are you involved in any activism?

HB: Well, the community definitely influenced me. I’m good friends with one of the residents who was co-managing the building with Isa for the last 30 years, and I learned a lot about her life and her activism through Martin Cox. I’ve been an activist at numerous points in my life, definitely more marches when I was younger, and now I think it’s more of a private practice for me. I try to give what I can financially and interpersonally, though there’s always a lot to learn and to do. But being in Isa’s space was really quite humbling, simply because her book collection had me thinking that I need to study harder. This woman was well-read, and if her collection is any indication of what she was going through in her life, her study of socialism, Black American history, and American, European, and African politics, is all so fascinating. I was really inspired to learn more and to actually be, hopefully, a better citizen.

Hayley Barker, Isa’s Wall of Photographs, 2023, oil on linen, 65 x 80 in. (165.1 x 203.2 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

Hayley Barker, Isa’s Wall of Photographs, 2023, oil on linen, 65 x 80 in. (165.1 x 203.2 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery and the artist. Photo: Nik Massey

SSA: How did the artist residency at Laguna Castle come about? Because it seems like it wasn’t quite formal at the time?

HB: The board of directors of the nonprofit organization that arranged the residency, Latitude for Art, invites artists, musicians, writers, and comedians to participate in creative projects across Southern California—and I was recently elected to the board, which is very exciting. It was an informal invitation by Martin Cox and Thomas DeBoe, the founding directors of Latitude for Art, so I was really honored to be the first artist in this residency’s L.A. iteration. He has lots of plans for future residencies, so it should be pretty interesting to see how things unfold there and across other interesting spaces in L.A. with different populations.

Something that I loved learning about Isa was her work with people with disabilities, and I love the idea of working with a wide variety of communities that don’t usually intersect. Martin was talking about perhaps doing some work at a senior center where everyone is involved, including the senior center’s residents, and I think that could be a really dynamic way of thinking about an artist residency. To me, art does its best work when it’s in the world, and we are of the world, so it’s really nice to try to remember our communities out here.

SSA: You recently did a printmaking collaboration with Utopia Editions, David Zwirner’s publisher of fine art prints, featuring landscapes inspired by your garden. Did you have any previous experience with printmaking?

HB: I did not have any printmaking experience. Working with James and Peter Pettengill at Wingate Studio was the opportunity of a lifetime to learn how to make an etching. I had a really incredible time learning the process and hope to do more etchings in the future. I owe great thanks to David Zwirner and Utopia Editions for pairing me with Wingate. It’s hard for me to think of a better creative match.

Proofs of Hayley Barker’s new six-plate etching at Wingate Studios, New Hampshire, 2023. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Photo: Tony Luong

Hayley Barker’s new six-plate etching, New Yard, Elysian Heights, being printed at Wingate Studios, New Hampshire, 2023. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner. Photo: Tony Luong

SSA: Your first solo show in Asia, Last Morning at El Centro, at the CVG Foundation in Beijing, also included some paintings inspired by Laguna Castle and your garden at your old home. You recently moved, so what has it been like creating depictions of the garden in your new home?

HB: The garden landscape of my new home is still revealing herself to me. Just this morning I set up a table and chairs nestled into a large succulent patch. I think it will be a fertile place to talk to the goddess and watch the sky.

SSA: What do you have planned now that your solo shows in L.A. and Beijing are over? Are you currently working on anything else besides painting?

HB: I’m a latecomer, but I love gardening and it is absolutely my favorite activity on my days off. And my new place has a bigger yard, so I’m excited to start building some new painting compositions. I’m pretty much just going to be painting, which is such a huge blessing. And I’ll be doing some traveling, but mostly I’ll be putting together my new garden and I’m pretty excited about that. It’s part of the practice.

Hayley Barker, Laguna Castle: Staircase of Plants, 2022, oil on linen, 100 x 82 in. (254 x 208.28 cm). Image courtesy of Night Gallery. Photo: Nik Massey