The Joys of Feminist Archiving: Two Southern California Shows

by Janet Sarbanes

Installation view of The Feminist Art Program (1970-1975): Cycles of Collectivity at REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Yubo Dong, ofstudio

The first thing to catch my eye on my last visit to The Feminist Art Program (1970-75): Cycles of Collectivity, at REDCAT gallery was a letter from art historian Amelia Jones to the former president of CalArts, Steven Lavine. Presented in an open binder filled with documentation of student-led initiatives to reclaim the history of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts, it lauded their efforts and challenged the continued erasure of the program from official histories of the Institute, which focused largely on lists of illustrious alumni. “You must certainly know,” Jones’s letter to the president reads, “that the Feminist Art Program is one of the greatest legacies CalArts has offered the world.”

Cycles of Collectivity constitutes long overdue institutional recognition of the Feminist Art Program and yet stays true to these DIY student-initiated engagements—and to the feminist pedagogy and organizing that preceded them—in its intimate scale, hands-on library, and welcoming gathering space. The show is a tribute to feminist archiving, whether embodied in documentation of the CalArts Feminist Art Program (FAP) and its counterpart, the often-overlooked Women’s Design Program founded by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville; or the two pedagogical experiments that book-ended them elsewhere: Judy Chicago’s initial feminist art program at Fresno State and the Feminist Studio Workshop at the L.A. Woman’s Building. And it makes meaningful and generative connections to the archival practices of feminist artists working today.

In addition to the archival materials from the seventies spotlighted in vitrines and binders, the exhibit includes contemporary works commissioned or repurposed from CalArts alums. Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz Starus’s The Performing Archive, twelve videos of diverse young women artists speaking about items that compelled them in Lacey and Starus’s own feminist archive, provides almost a meta-discourse on how to move through the show: choose ten things to think about. Gala Porras-Kim’s More Letters to A Woman Artist, a modern-day expansion of the FAP publication Letters to A Woman Artist, which asked women artists to write open letters to the next generation, and Women Artists Register Update, which adds to the original slide collection created by Chicago for pedagogical use, underscores the continued need for more ways into artmaking for women and more attention to the work they do make.

Installation view of Suzanne Lacy and Leslie Labowitz Starus, The Performing Archive, 2007-2023, in The Feminist Art Program (1970-1975): Cycles of Collectivity at REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Yubo Dong, ofstudio

Installation view of ak jenkins, Field Work: Weight into dust, 2023 (left) and Gala Porras-Kim, More Letters to a Young Woman Artist (detail), 2023 (right) in The Feminist Art Program (1970-1975): Cycles of Collectivity at REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Yubo Dong, ofstudio

ak jenkins’s Field Work: Weight into Dust opens up further possibilities for feminist archiving in the world of sports, documenting the collective praxis of women shotputters, including the first American woman to medal in the sport, Earlene Brown. Ekta Aggaarwal’s “map” of feminist pedagogy at CalArts, which includes syllabi for perusing, provides a snapshot of the five decades since the Feminist Art Program, revealing increasingly intersectional approaches in the classroom. Through this juxtaposition of the old and the new, the exhibit throws into relief the overwhelmingly white, cis, and middle class composition of the FAP faculty and students, while allowing for continuity—and difference—of perspective in the work of a more diverse group of artists.

While foregrounding feminist archival practices, old and new, Cycles of Collectivity attentively tracks the early development of feminist art pedagogy, which continues to startle and inspire. The Womanhouse experiment that kicked off FAP, with students and faculty taking over a condemned mansion in Los Angeles and transforming it for one month into a giant installation exploring women’s relationship to domesticity and the home, stands the test of time as a radical intervention into the discourses of art and feminism. The pedagogy developed by Chicago and Miriam Shapiro at CalArts combined consciousness-raising sessions grappling with women’s personal experiences of domination in familial, community, religious, and institutional settings with research into women’s issues and the history of women artists—all with an eye toward helping their students find new and relevant subject matter for their work. It models one pathway among others taken in the sixties and early seventies (Black Arts comes to mind) to disrupt universalist discourse surrounding art and artmaking so that new meanings and forms, sociopolitical and aesthetic, could come into being.

Installation view of Andrea Bowers, Generation After Generation (Judy Chicago and Andrea Bowers discuss the Feminist Art Program), 2023 (center), and Political Ribbons (REDCAT), 2023 (surround), in The Feminist Art Program (1970-1975): Cycles of Collectivity at REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Yubo Dong, ofstudio

One of these forms was feminist performance art, which Chicago describes in the revealing 2023 video interview with Andrea Bowers commissioned for the show as “a very direct way for women to access the subject matter in their experience and translate it into images.” Though she acknowledges that some of the most compelling FAP performances were process rather than image-based, drawing attention to women’s work (cooking, ironing, cleaning, grooming) that went unseen, Chicago is frank about her own interest in developing a new iconography through her work in FAP, and her perception of the new pedagogical and artistic practices developed there as a means to that end, rather than an end in themselves.

I was lucky to see another feminist archival exhibition that ran almost concurrently with Cycles of Collectivity, this one dedicated to the journal Heresies: A Publication on Art and Politics (1977-1993), which reinforced my sense that archival shows are not merely the best way to understand currents in seventies feminist art and activism, but to form an active and personal connection to them that can energize both practices in the present. Heresies: Still Ain’t Satisfied was culled from curator Judith Rodenbeck’s personal collection and featured enlarged covers of selected issues as well as vitrined selections from the issues themselves, alongside editorial content and a small library of related reading material.

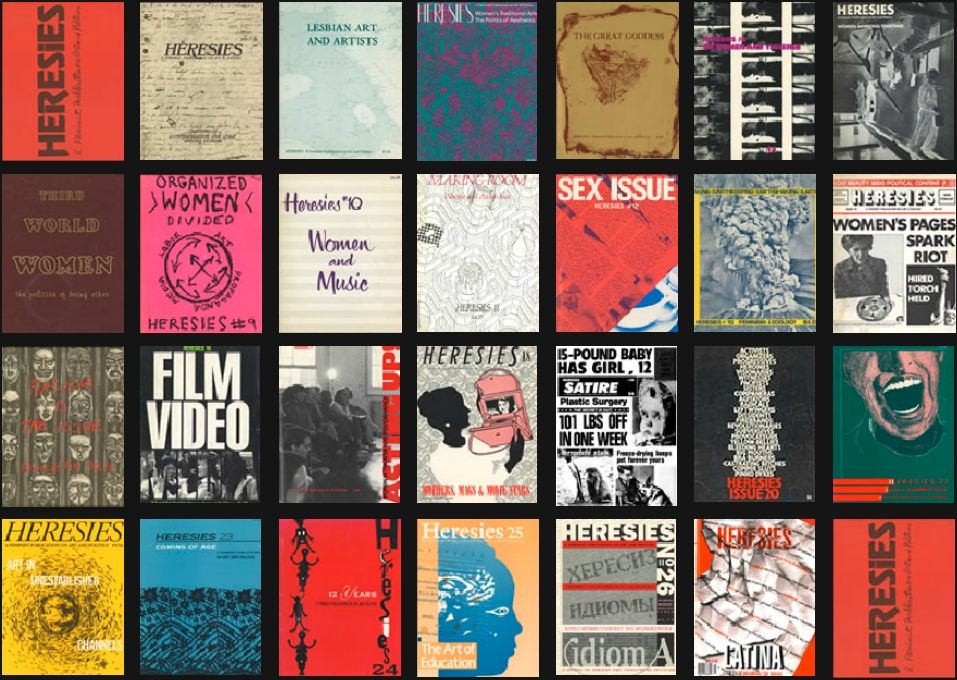

Assorted covers of Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics (1977-1993).

My own perusal of the exhibit alighted upon issues titled Feminism, Art and Politics; On Women and Violence; Women Working Together; Third World Women; Women and Music; Making Room: Women and Architecture; Sex Issue; Film/Video/Media; and Lesbian Art and Artists, each opening up a world of possibilities on the way to realizing the journal’s stated mission: “We are not only analyzing our own oppression in order to put an end to it, but also exploring concrete ways of transforming society into one that is socially just and culturally free.” The journal’s editorial model was as feminist as its themes, offering up another means of generating cycles of creativity besides the pedagogical and the archival: “Each issue was crafted by a new editorial collective of volunteers who organized it around a particular theme related to art, theory, and politics. This collective ethos meant that over the course of its run, hundreds of individuals participated in the production of the magazine, enacting a collaborative feminist practice of meaning-making.”

In her interview with Bowers in Cycles of Collectivity, Chicago shares one of the earliest pedagogical strategies she used with her FAP students: “I made them introduce themselves with their full names—which shocked them because they were only ever Suzy or Nancy, never were they taken seriously, or what they had to say.” Though of course those full names were patronymics, Chicago’s insistence on respect for these young women artists from the very outset is instructive. A deep respect for the individual and the collective endeavor is evident in both exhibitions described above, a hallmark of feminist arts practice we must renew over and over again.

The Feminist Art Program (1970-75): Cycles of Collectivity is on view at REDCAT until February 18th. The exhibition was organized by REDCAT Chief Curator and Deputy Director, Programs, Daniela Lieja Quintanar, with Assistant Curator Talia Heiman, independent curator Lucia Fabio, and artist/curator Ekta Aggarwal, with research support by Ana Briz, Julia Raphaella Aguila, Arantza Vilchis-Zarate, and Yishan Xin. The exhibition was designed by Kim Zumpfe. Janet Sarbanes, Curatorial Advisor, served as a faculty liaison to the CalArts archive and the CalArts community.

Heresies: Still Ain’t Satisfied, curated by Judith Rodenbeck, Chair of UCR’s Department of Media and Cultural Studies, and Ashley McNelis, CMP Curatorial Fellow, was on view at the Culver Center of the Arts from July-January 2023. While the show has come down, you can find the digitized archive of Heresies here: heresiesarchive.org

Installation view of The Feminist Art Program (1970-1975): Cycles of Collectivity at REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Yubo Dong, ofstudio

Heresies: Still Ain’t Satisfied exhibition at UCR ARTS, Riverside, CA. Photo by Nikolay Maslov.