View from the Inside Out: Julie Becker’s Los Angeles

by Jean Watt

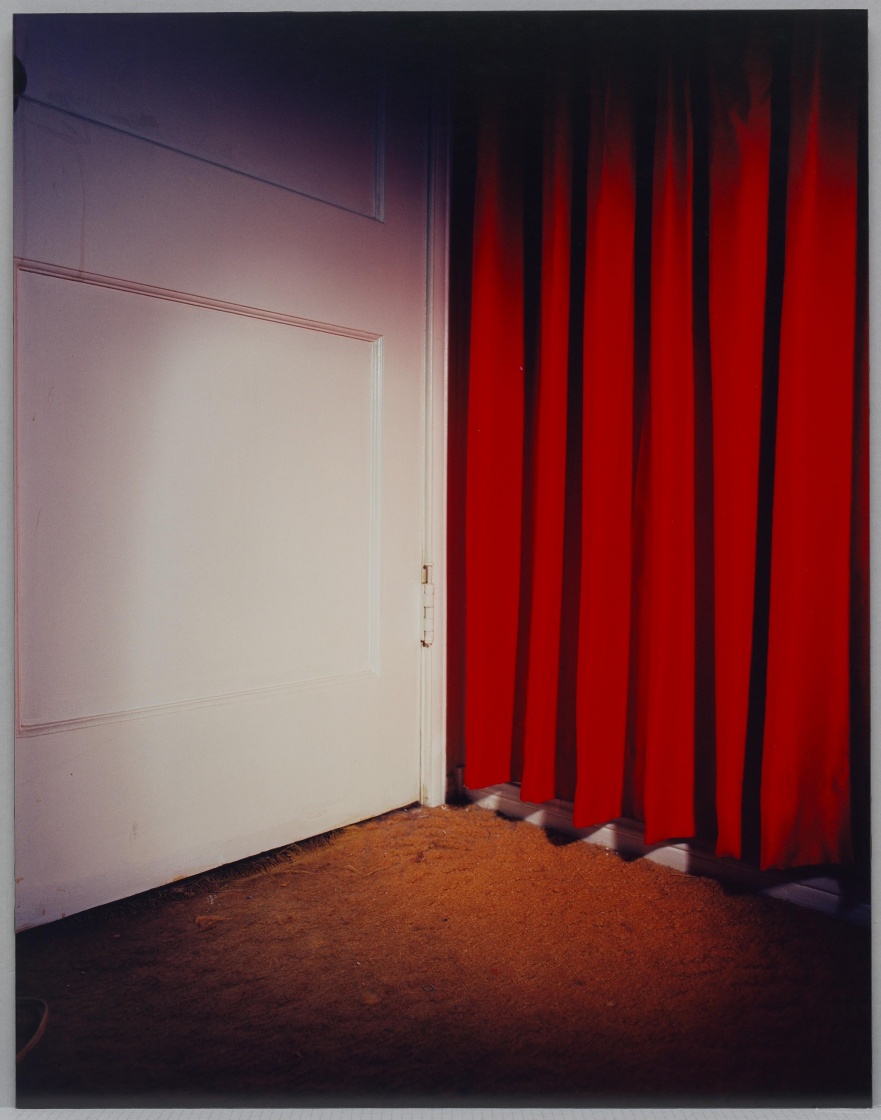

Julie Becker, Interior Corner #6, 1993. Chromogenic print, 35 3/8 x 27 1/2 inches (89.9 x 69.9 cm). Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

In 1996, Julie Becker graduated from the CalArts MFA program with her thesis work Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest. The multi-room installation reproduced interior spaces at different scales, a motif which appeared throughout Becker’s practice in assemblage, drawings, and photographs. These spaces were drawn from Becker’s own living situations in Los Angeles as well as fictional models like the hotels portrayed in The Shining or the Eloise books. Becker’s imaginary rooms existed alongside her memories of real ones to produce a world which blurred the edges of her lived reality. An engagement with domesticity emerged naturally from this fascination, with traditional home settings appearing throughout Researchers. But more than this, Becker interrogated the function of her interior spaces to recreate rooms which resembled both domestic and commercial property, bearing ghostly traces of supposed residents or visitors but which had been abandoned and repurposed to become something else. Rooms could be both hotel lobby and doctor’s waiting room, both bedroom and artist studio, both storage and office space.1

Soon after her graduation from CalArts, Researchers was exhibited at the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1996 and at the Kunsthalle Zürich in 1997. Despite this early success, Becker spent the rest of her life on the fringes of the mainstream art world struggling with poverty, addiction, and mental illness. After her suicide in 2016, aged 43, the retrospective exhibition, I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent, travelled from the ICA in London in 2018 to MoMA PS1 in 2019, taking its evocative title from a 2015 drawing. Researchers was shown in its entirety. Becker received momentary posthumous attention, with much of the criticism focusing on what Richard Birkett described as the “psychic spaces” of her work to draw parallels with her psychological state.2Charlie Fox’s 2018 review of the ICA exhibition concentrated heavily on the eeriness of the spaces she produced, a sensation posed to have been heightened by the artist’s cause of death.3Similarly, Jocelyn Miller’s criticism developed the “psychoaesthetic” nature of Becker’s practice.4Although it is important to recognize the personal context of her work, the repeated emphasis on Becker’s psychiatric health denies a much more expansive reading of her practice. Researchers presented us with a mode of producing space for the self which not only emerged from internal struggle, but from the specific living conditions in Los Angeles in the 1990s and beyond. It reveals a precarious way of being, born from a city which was—and still is—unwelcoming to the survival of artists. And through this, it proposes an elastic understanding of space, where boundaries are both unnecessary and impossible, where the objective is simply to find a place to rest.

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest, installation view, “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, June 8-August 12, 2018. Photo: Mark Blower.

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest, detail view, in “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” MoMA PS1, New York from June 9–September 2, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Growing up in and around Los Angeles, Becker spent much of her childhood moving between a series of low-rent apartments with her artist parents. It is possible that some of these residences were Single Room Occupancy hotels (SROs), a type of affordable housing with a long history in many American cities.5Fueled by years of city planners’ and politicians’ attempts to cast their low-income residents as dangerous, and exacerbated in popular culture by 1930s detective novels set in Bunker Hill and the infamous and ongoing stories of the Cecil Hotel, these hotels soon became associated with fear in the city’s public imagination.6Whilst Becker’s lived experience in SROs is speculative, hotel-like interiors creep into Researchers, nodding to this type of transient housing which had also become shorthand, through a nationwide myth-building, for spaces seen as haunted or unsafe.7Becker’s struggles with stable housing continued into her adult life with many years spent in an Echo Park home owned by the California Federal Bank whose building loomed above it, a home which Chris Kraus described as “a shack falling into the ground.”8The space was originally intended for Becker’s studio, but it became slowly apparent that this would also be her long-term abode. After the occupant living in the basement apartment had died of AIDS, the bank allowed Becker to utilize the space for free in exchange for clearing out his belongings.9Instead, she cut a hole in the floor of her own living room-studio above and recorded herself lowering a model of the CalFed bank into the basement, a work which would expand amorphously into the unfinished project, Whole. Whilst in Researchers the role of Becker’s own lived circumstances remains uncertain, in Whole her home undeniably merges with the work. This dramatic collapse of boundaries reveals a pliability to the space which surrounded Becker and fed into her practice, an ability to move from fiction to reality without being detected, to occupy both realms at once.

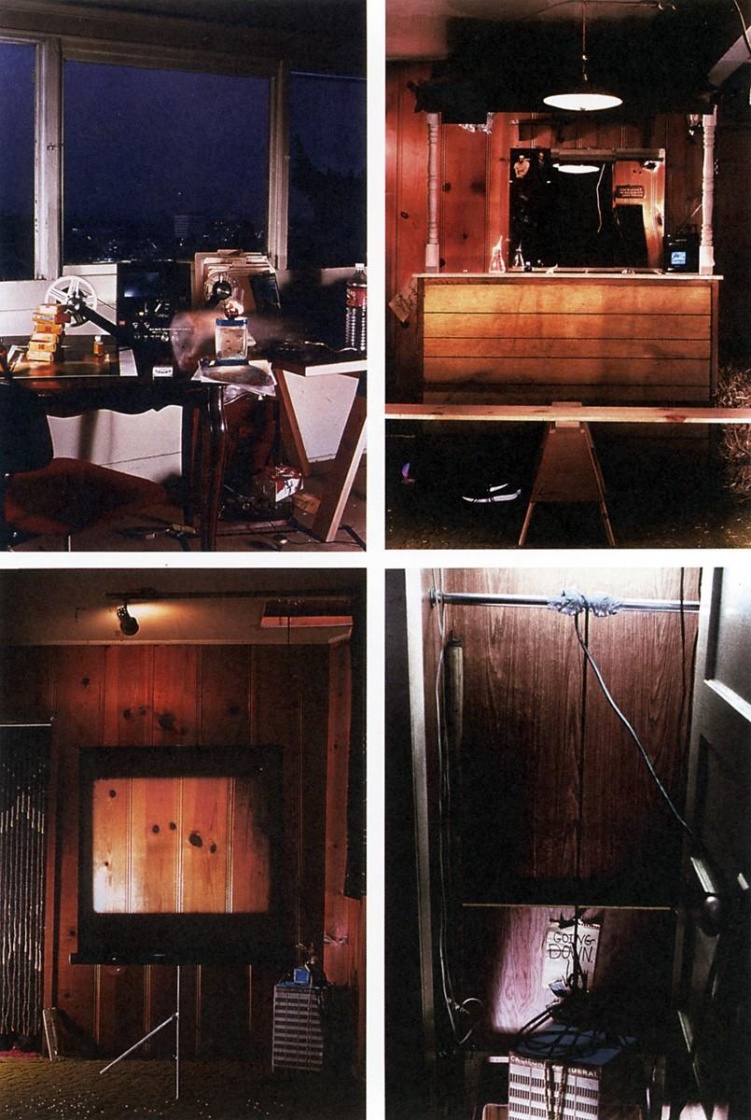

Julie Becker, Whole (Projector); Whole (Bar); Whole (Screen); Whole (Going Down), 1999. C-prints on aluminum, 128.9 x 85.7 cm each. Courtesy of CalArts Visual Resource Collection.

Becker’s practice emerged out of a specific cultural moment in Los Angeles in the ‘90s when notions of domesticity and occupying space were also being examined by other young artists, from Diana Thater’s Up to the Lintel: Bliss to Andrea Zittel’s Living Units.10This came as a response to the lived experience of Angelenos at the time, which was characterised by precarious civic conditions. The rapid economic growth and globalization of L.A. had produced a city defined by its social fragmentation and polarization of class, with extreme wealth existing alongside extreme poverty. An obsession with privatization and domestic security had further widened the class gap.11The housing crisis came hand in hand with mass unemployment rates, with 562,000 jobs lost in the 1990s in L.A. County.12It was a decade defined by cultural blight, marked most significantly by the 1992 riots in response to the acquittal of the LAPD officers who beat Rodney King. The lead up to this period of social unrest is vigorously dissected by Mike Davis’ urban history City of Quartz (1990), which examines the shaping of contemporary Los Angeles through racial and economic issues. Davis specifically suggests that processes of housing segregation belonged to a class violence which was deep-rooted and historically established in how space had been divided in the city.13Moreover, the disparate, multi-centered nature of the city’s geographical spread had encouraged an individualistic manner of living which further ostracized those on the margins, unable to access the type of lifestyle which was being fostered in Los Angeles: private, secure, distant from others. For urbanist and theorist Edward Soja in his 1989 book Postmodern Geographies, the effects of this were visible in as many as 250,000 people living in “transformed garages and backyard buildings, with half as many crowded into motel and hotel rooms.”14These conditions have not improved today: for the last three decades, L.A. County has been the most housing-overcrowded county in the United States.15

In Researchers, Becker drew on these living conditions to produce an installation split into three distinct sections: a life-sized ‘waiting room,’ a room containing two miniature models of interior spaces, and a backroom office-storage space. In the middle room, three cardboard refrigerator boxes stand empty and upright across two alcoves with a fourth box lying on its side padded with green foam. The floor is lined with more flattened boxes. In the center of the room, the two sprawling models of maze-like interiors sit low to the ground on wheeled plywood boards. Viewers must peer down or crouch to inspect their mysterious components: rooms with makeshift beds or sleeping bags, unusually long corridors, a vast red bathroom, a pool and darts room, rooms which could be offices, libraries, dining rooms, or living rooms. Any connection between these spaces seems left intentionally incoherent, disjointed from expected layouts of the home, hotel, or workspace. Instead, elements of each of these spaces come crashing together, merged into being. What is consistent in the models is a makeshift quality to the homebuilding: carpets are not quite stuck down, plexiglass balances on the tops of corridors, walls are imperfectly aligned, dried glue oozes out of corners. Some of the furniture seems to come from dollhouses, ready-made and store bought, while other pieces are built out of toothpicks, plasticine, and different found materials. These recall Soja’s description of transformed garages—miniaturized evidence of improvised ways of living which were becoming commonplace in the city. The cardboard refrigerator boxes which surround the models are posed, in this context, as another type of private space. Anthony Hernandez’s Landscapes for the Homeless (1988-1991) flickers into view, a photo series documenting the temporary structures offering refuge to those struggling with homelessness in L.A., using cardboard boxes as sleeping mats, curtains, windows, and walls. In Becker’s own words, “A refrigerator box, in American cities, can be the last refuge of the homeless.”16

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest, detail view, in “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

An understanding of the transitory experience of occupying private space is evident through each of the three rooms of Researchers. The ‘waiting room,’ which features a desk and name plate, a green banker’s lamp, a glowing blue fish tank, and a closed dossier file, also has a series of alternative name plates on a square of red carpet beside the desk: ‘Real Estate Agent,’ ‘Psychiatrist,’ ‘Entertainment Agency,’ ‘Concierge.’ The room exists as each of these sites and none of them, establishing a work which from the beginning is bubbling with liminality and spatial in-between. Behind the desk hangs an unlabelled set of floor plans, seemingly referring indirectly to the miniature models that follow. A two-seater leather sofa, a cabinet with a copy of Vogue, a Stephen King special T.V. guide, and a used ashtray cast the room as a doctor’s reception area, a hotel lobby, or a travel agency. It seems to be priming us for something more permanent beyond which Becker does not satisfy, with further versions of semi-inhabited transitory space in the next room. Becker mimics these types of spaces in her drawings, some of which were presented with Researchers in the retrospective I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent. Entertainment Center (1996-7) is an almost empty page filled with floating objects: a small wooden building, a pair of shaded columns, some half-finished window-like shapes, balloons, a speaker.17 Mysterious Round Object and Incomplete Chair (1996-7), with its strange high shelves, singular chair, faded sofa, and glowing yellow orb in the corner of the room recalls the energy of the waiting room.18

These in-between spaces—not quite occupied or abandoned, not domestic or commercial—emerge from a city where transience is not just a state of living, but a state of development. L.A.’s gas stations, parking lots, and retail complexes typify a city (and post-industrial America as a whole) made up of spaces meant to be passed through. Becker’s own Echo Park neighborhood, as described by Mark Von Schlegell in Mousse, was “mostly taken up by gas stations […] and flimsy, low-income rental units,” following years of decline in the area.19This landscape has drastically changed over the last decade with the rapid gentrification of Echo Park and its neighboring areas in and around east L.A.20Back in the ‘90s, Becker lived illegally in a storefront studio designated as a commercial space, with the towering presence of the California Federal Bank building—now Citibank—overhead.21 In areas such as these, commercial and industrial development cross-pollinates with residential tenancy. Further inflamed by California’s culture of NIMBYism, unsightly developments are blocked from wealthier residential areas and pushed instead into areas of low income housing among the commercial complexes and freeways. In a 2011 Eastsider article, the ominous presence of CalFed—its building noticeably the only hi-rise in the neighborhood—was speculatively posed as the reason that many Echo Park residents may be scared of heights; speculation aside, its height disturbed the surrounding residential space.22 The bank also began seeping into Becker’s practice. In drawings such as Untitled (Whole Series) (2003), where the words “Top Floor in CalFed (Or Part of It) is Top Floor of House” are scrawled above a table and window setup, it is as if the uncertain limits of Becker’s home overlapped with the boundaries of the bank itself. Additionally, in 1910 West Sunset Blvd (2000) Becker reproduced a section of the pavement outside the bank building, complete with a manhole cover and street graffiti, where a discarded floral slipper highlights the proximity to home.

Julie Becker, 1910 West Sunset Blvd, 2000. Mixed media sculpture, 99 x 52 x 16 inches (251.5 x 132.1 x 40.6 cm). Image courtesy of Greene Naftali.

The transitional nature of the spaces that Becker reproduced makes sense within the narrative of a city defined by cars and freeways. In Becker’s own words, the experience of Researchers is “like getting in your car and driving without any particular destination.”23In these terms, the form of the installation encourages a durational engagement with the work, but the content disorients. The specific function of each of Becker’s rooms floats between possibilities of impermanence and therefore denies any settling point for the audience. The decision to place the miniature models on wheels also becomes significant here, reminding us that the miniature rooms could be further shifted and rearranged. This echoes the reality of many housing situations in Los Angeles, where vehicular homelessness is widespread: in 2016, nearly 20,000 people were residing in RVs, cars, and vans.24Cars are also an inaccessibly expensive mode of transport for many in the city, with gas prices nearing $6/gallon in 2023.25In Becker’s 1999 drawing Untitled (Cars and Smog), shown at Greene Naftali in 2016, a mostly blank page is populated by a selection of floating cars, peppered with a foggy spray. The experience of car travel hangs over Becker’s work not only as a governing symbol of the city, but as a mode of existence which is transitional. To navigate Becker’s practice is to do so temporarily. Ghostly, the cars haunt the drawing, merging indistinguishably with the smog hovering over the city, inescapable.

Julie Becker, Untitled (Cars and Smog), 1999. Mixed media on paper, 12 x 11 inches (30.5 x 27.9 cm). Image courtesy of Greene Naftali.

There is a ghostliness present across Becker’s entire body of work. It seeps out of Becker’s embedded investigation into precarious domesticity and in turn becomes related to the uncanny. This interest in horror and the uncanny was also reverberating more broadly throughout contemporary art practice in the 1990s, in what Christoph Grunenberg describes as “the contemporary Gothic,” embodied by artists such as Jake and Dinos Chapman, Gregory Crewdson, Cindy Sherman, and Abigail Lane.26Intertwined with the American Suburban Gothic in film and television (American Beauty, Twin Peaks) these practices used the site of the home as a festering pot for the grotesque, dark, and unsettling. Take Becker’s Interior Corners (1993): a photographic series of closely cropped corner spaces, both full-sized and miniature recreations (with no definable differences), starkly lit and shot with a flash. They read like crime-scene documentation mixed with cheap family photographs. Interior Corner #6 (1993) is a brightly lit white door, rusty orange carpet, and plush red curtains, as if extracted straight from David Lynch’s Red Room.27A similar red velvet curtain features in one of the rooms in Researchers, as well as a miniature replica of the photograph. Becker’s spaces are haunted by the presence of the whole of her work, which threatens to force itself into every crack. Whole, of course, was the pinnacle of this: a work which threatened to keep expanding until it contained Becker’s entire existence. In her drawings, too, forms are scattered throughout her vast empty pages just as objects are scattered through the empty rooms of her sculptural work. The vacuum of the work seems to be magnetic, absorbing fractured pieces from other locales.

Installation view of “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

In Barry Curtis’ Dark Places: The Haunted House in Film, Curtis echoes this sentiment to suggest that “the flexing of margins and the refusal of objects to stay stored in place or within the limits of their customary significance” is symbolic of the haunted house.28Becker’s boundaries are malleable: life-sized objects alongside miniatures; drawings with no clear edges; spaces which could have many different functions. The cardboard boxes which surround the models, in Curtis’ language, follow a theme of packing and unpacking in haunted house films as a moment of promise but also of tension and transience.29The abandoned miniature U-HAUL truck at the corner of one of the models amplifies this sensation, suggesting residents are in the process of moving in or (being moved) out. Transience hovers over Researchers; the interiors exist as both SROs and haunted houses, their elements of spookiness inseparable from the conditions of living precariously on the edges—the slippage is purposeful. As Anthony Vidler succinctly proposes in the Architectural Uncanny, the contemporary unhomely is characterized, in part, by the struggle for domestic security in the modern age which destabilizes the relationship between house and home, one that is now fraught with alienation, estrangement, and homelessness.30

The push and pull between living on the margins and haunted houses is fuelled by the gasoline of Hollywood which careens around Becker’s work. The strange temporariness of the movie set occupies the still point between these two types of spaces: semi-occupied, half-constructed, part stage, part home. Researchers, to Peter Wollen, “looks like a film set after the crew have left without anyone taking the trouble to clean up”: beverage cans and miscellaneous papers scattered around rooms with no roof.31In Thom Andersen’s video essay Los Angeles Plays Itself, he dissects the ever-presence of the movie set in the city, from seemingly functional buildings which are in fact permanent movie sets, like the City of Industry’s fake McDonald’s, to now purposeless buildings that are preserved as movie locations, like the Ambassador Hotel. Hollywood crawls into Beckers’ other works, too: in Suburban Legend (1999) shown in the ICA retrospective, Becker plays Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon over The Wizard of Oz in an hour and 45 minute examination of the legendary alternative stoner soundtrack to the film.32Becker acknowledges in her own words that “just as in an art-directed movie set, these things [in Researchers] are intentionally arranged.”33Self-referential and self-aware, through her practice Becker is constantly backtracking and rewriting, returning to places she has already been in her work as well as in her life. According to Mike Davis, L.A. is “the most mediated town in America, nearly unviewable save through the fictive scrim of its mythologizers.”34Becker is her own mythologizer. We view her life through the fictive scrim of her work, and vice versa.

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest, detail view, in “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

Julie Becker, Researchers, Residents, a Place to Rest, detail view, in “Julie Becker: I must create a Master Piece to pay the Rent,” MoMA PS1, New York, June 9–September 2, 2019. Photo: Matthew Septimus.

These processes of viewing filter through Becker’s work, in a state of study and also of paranoia. The back room of Researchers seems to be occupied by a ‘Researcher’ character, evident in the detailed notes they’ve written, like a professor or a therapist, about the supposed inhabitants of the miniature models. The CalFed bank permanently hovers over Becker’s shoulder. The work’s perspective also always seems to be from above, with its buildings in miniature, and its drawings relating the open emptiness of a birds-eye landscape. This extends outside of Researchers to drawings such as Untitled (Roller Coaster Scaffolding) (2000)35and Helicopter (1999). The helicopter especially is a vantage point familiar to L.A., and one which goes hand in hand with images of the city’s destruction, from T.V. footage of the 1992 riots to Ed Ruscha’s 1965 painting L.A. County Museum on Fire to the burning flare stacks in the opening shot of Blade Runner’s post-apocalyptic skyline. As posed so succinctly by Norman Klein, “L.A. is supposed to die by fire, earthquake, suffocation, amnesia, in the dark, in a movie theater, or in some way seen from a distance.”36Becker thus keeps us at arm’s length from destruction. She shows us from far away what is still standing: the models in Researchers have not yet collapsed, her later drawings—dream house accessory and the watering series—glimmer with iridescent paper. This is Sabrina Tarasoff’s overarching opinion on Becker’s work, that it “is moved by the tendency of lives to sink downward, smash, and still somehow survive.”37Perhaps more accurately, it is a lesson in how to teeter on the edge of everything forever.

Whole comes the closest to bringing us into its own destruction, in its “endless exposing of parts and not ever reaching a whole.”38Unfinished at the time of Becker’s death, it is a series of works which sinks closer and closer into the artist’s own world. In Whole (Bar) (1999),39an image shows a shoddily constructed basement Tiki bar with bannister posts on either side holding up a strange decorative roof. The Tiki bar was constructed by the previous resident of the basement apartment and became part of Becker’s work after she moved in, reproduced through photographs featuring a pair of Nike trainers on the olive carpet, a finger-printed mirror on the back wall reflecting the ceiling lamp, a glass conical flask glistening in the light. In Untitled (“Tiki Bar”) (2001),40Becker diagrams the structure paired with a garish rainbow sticker at the base of the page. In Whole (Screen) (1999),41a projector screen sits in front of a wall of orange-brown wood panelling, the screen itself showing a section of the wall. The tiny model of the CalFed building in the corner is tied with rope which leads up through the ceiling. It is clear we are in the basement featured in Federal Building with Music (2002),42where Becker once lowered the model down through a hole in the floor of her apartment. The hole we can see in the ceiling must lead back into Becker’s apartment above, but the scale of the room is disorientating. The ceiling feels slightly too low; the legs of the projector screen seem short; the model of the bank tower is only a quarter of the room’s height. It feels like the image could have come from Becker’s Interior Corners series—perhaps the whole room is a model and not her actual dilapidated home. Perhaps it is easier to fathom that everything is the work, not the melting pot of Becker’s work and life. Unlike the miniaturization of the spaces in Researchers, the elements of Whole press into Becker’s daily existence to reveal a chaos which is harder to confront in full size.

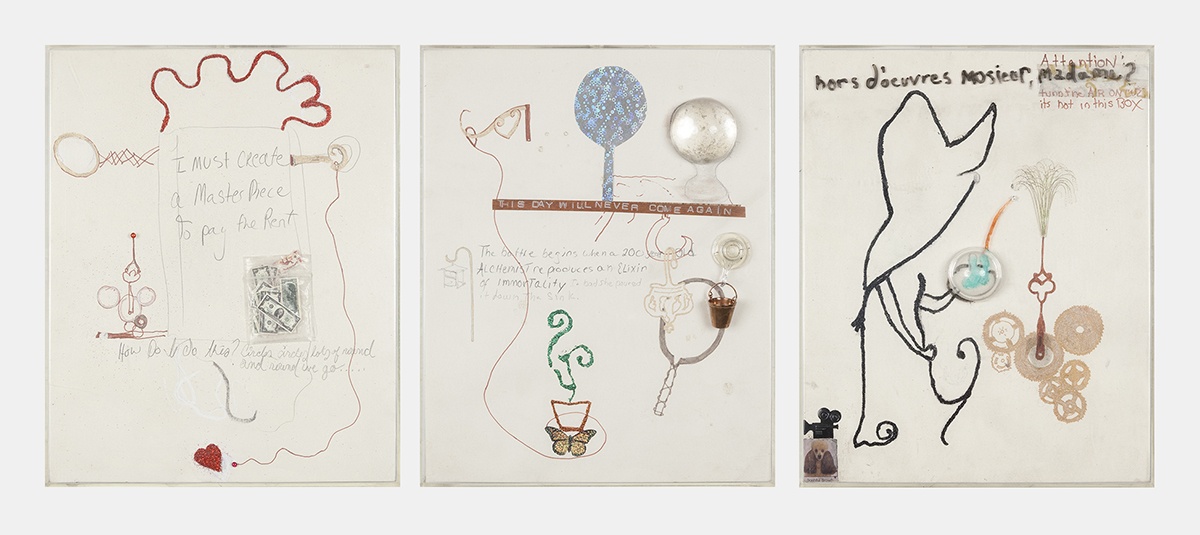

In Becker’s later drawings her world-building becomes more dreamlike and even less tied to reality than before. Untitled (2007)43is an ornate wood-panelled mirror, with a shimmering iridescent pane. Two smaller mirrors are attached on either side. One of the circular panes looks like the surface of the moon; at the bottom are the words ‘Astral Voyager,’ ‘Spirit,’ ’Energy,’ ‘Form,’ and ‘Matter’—a language of navigation through something otherworldly. Elsewhere (2015) shows three women, one with a halo and one with a cloud in place of her head, walking dogs around the page. The figures float through space, angelic and also alien. In the triptych watering (2015), from which the words ‘I Must Create a Masterpiece to pay the Rent’ were lifted from for Becker’s retrospective, the letters are scrawled in the center of a strange selection of objects: a plastic wallet of dollar bills, a glittering red heart connected to a squiggly thread, a series of circles which looks like an alarm clock. Other words which feature through the three drawings are at once astute and agonisingly painful: How do I do this? Circles, circles, lots of round and round we go… This Day Will Never Come Again. Becker’s ways of making were obsessive and furious, born from a need to comprehend and describe the world despite, or perhaps because of, her precarious circumstances. In a city where, particularly as an emerging artist, it was—and still is—nearly impossible to find space for oneself, Becker, both inhibited and invigorated, tried again and again. In an interview in 2006, she was asked, “What makes you angry? What makes you feel free?” To both questions she answered, “Poverty, poverty.”44

Julie Becker, watering, 2015. Mixed media, 10 3/4 x 8 3/8 x 1 1/2 inches (27.3 x 21.3 x 3.8 cm) each. Image courtesy of Greene Naftali.