Artists at Work: Pippa Garner “Back to Zero Again”

by David Matorin

Pippa Garner, Specimen Under Glass, 2018, Framed photograph, 25 x 18 1/2 x 1 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

Pippa Garner is an artist of many in-betweens. In a career spanning multiple decades, she has bridged the chasms dividing art from design, publishing, media, and lived experience. Always with an edge of sardonic wit, her absurd and accessible drawings, sculptures, and characters cast a satirist’s trenchant eye toward the systems of authority and myth that shaped the Boomer Generation’s American experience. First trained in automotive design at ArtCenter in Pasadena, she was drafted and served as a combat illustrator in Vietnam for the U.S. Army before returning to Los Angeles to become a fixture of the city’s vibrant artist communities of the 1970s and ‘80s. Her books, Philip Garner’s “Better Living Catalog” (1982)1and “Utopia… or Bust!: Products for the Perfect World” (1984),2which depicted facetious consumer products created by a fantastical author-inventor character that she often performed, led to appearances on national television programs like The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.3Her abandonment of that character in the late ‘80s to embark on her self-described project of “gender hacking” caused an estrangement from L.A.’s art world at the time, as well as a recent resurgence of interest in her status as a pioneering trans artist. Now an octogenarian resident of Long Beach, CA, Garner spoke to me by phone. Her retrospective exhibition, “Immaculate Misconceptions,” opened at JOAN, Los Angeles in 2021 and is on view at Verge Center for the Arts in Sacramento through September 25. Her first European solo exhibition at Kunstverein München, “Act Like You Know Me,” will open September 24.

David Matorin: Why don’t we start with your thoughts on the importance for artists to be surrounded by a community of like-minded people, especially at the early stages of their development, like the one you found here in the 1970s?

Pippa Garner: Well, it seems like in any creative field you need to have an energy that goes back and forth between people. You can do it alone to some extent—I sometimes feel like I have a mind within a mind that can play with things back and forth. But basically, the spark comes from something that’s got to be active. It’s got to have a vitality. Back in the ‘70s, I read Man Ray’s autobiography and it gave me a feeling of this environment in Paris in the ‘20s with André Breton, Gertrude Stein—all these people that were just brilliant, all creating this energy together, this buzzing. And as the buzzing settles, ideas form somehow. I always visualize it like a tornado, like The Wizard of Oz, the wonderful way that film illustrates the swirl of all these objects and people going up in this cyclone, and then landing, and becoming a new place. Things get sort of convoluted and confused and there doesn’t seem to be a way out. Then all of a sudden something comes along, some amazing force throws everything into chaos, and it lands again in this new configuration and it’s all fresh and full of spirit.

DM: You found your artist community in Los Angeles at the Los Altos Apartments on Wilshire Boulevard. What did you find so compelling about what was going on there in the late ‘70s?

PG: When I moved in to the Los Altos, I was in a serious romantic relationship. Nancy [Reese] and I had been in England and spent a good while there. We had just returned to the U.S. and were staying in New York City when we decided to go to L.A. via driveaway car. I don’t think they have that anymore. You used to be able to go to a car dealership and offer to drive a car that needed to be shipped cross-country. All you had to do was pay for gas. We found a brand new Cadillac that was supposed to be shipped to a dealer in L.A. and drove it out here. We didn’t know quite what to do once we got here, but somehow stumbled into this situation at the Los Altos. I don’t know how long it had been a residence for creative people, but the building itself goes way back to the ‘20s. It was built by William Randolph Hearst for Marion Davies.4 It was a beautiful building, six or seven stories, and it was really a show piece for her, a classy place. Film industry people lived there. Clarence Green lived there. He was the script writer for D.O.A., which was a film noir cult film from 1950. He was in his seventies, so there were some people there left over from the old days that had been there for years, but then all these younger creative people discovered this wonderful place that was fun to look at and be in, and it was relatively cheap.

View of the Los Altos Apartments at 4121 Wilshire Blvd., 2014. Photo by Bruce Boehner.

The Los Altos building was in Hancock Park at the time [present day Koreatown], a lovely part of L.A., so we started moving in. And for a decade or so, it became this really diverse community of artists. There were photographers, script writers… Nancy was a painter and my wife at the time—we got married while we were there—and there was just about every kind of creative person represented. You could go out and have coffee together or hang out in the lobby; there was a real sense of interaction. We could work together, you know, so it was a real stimulating place. We were poor, but we lucked out. Nancy and I were in the basement with Nancy’s paintings on one wall and my workspace on the other end. It was $300 a month and we split that and both got our careers going as part of that new generation of artists.5

That was also the WET magazine era. Leonard Koren was the Editor-in-Chief.6WET became this incredible vehicle for artists who were hot and yet poor and needed a way to get their work out there. You didn’t get paid anything, but you got your things published, it would be seen, and then you’d get other work from that. He also had these great parties and a lot of support from rich people in Beverly Hills. That’s another thing that sort of parallels the experience of Man Ray in the ‘20s. He had these wealthy patrons who just wanted to get involved with the art world somehow because it was a time of great change. It was an amazing culture, and then of course it disappeared. After that time nobody could get anything going in the same way, but it was such a link to what happened afterwards.

DM: What do you think caused that whole scene to dissipate? Where did it go?

PG: That’s the nature of California culture—it evolves. It’s the nature of all cultures, but I think that the rate of one thing morphing into another is much higher here than anywhere else. It was just part of what had to happen. It was time to go to the next step. We were all very ambitious. We wanted to get our work out there and make money and do all that. During that time too, I didn’t really identify myself as an artist so much. Since the time I was at ArtCenter, I didn’t know there was such a line of demarcation between commercial and fine art.

Philip Vincent Garner drawing in class at the Art Center School, 1961. Photo by Geoffrey Fulton. (2004.25.2755). © ArtCenter College of Design, Pasadena, CA.

DM: What year did you first arrive in L.A. to study automotive design at ArtCenter?

PG: I got there in 1961 when I was 19. I came out here right out of high school to go to what was then called the Art Center School on 3rd Street.7They didn’t become the ArtCenter College of Design until 1965. I was so young at that time that all I was thinking about was trying to have some fun, saying, “Hey, I’m going to college. There’s going to be parties and things happening.” When I got there I found out it wasn’t like that. They were all people, mostly, who had tried to get jobs as designers with degrees from regular colleges and were told, “Sorry, you’re not good enough. Go to either Pratt or ArtCenter.” So, these people were absolutely all business, trying to get through it, and it was upsetting. I was still a child in some fundamental ways, trying to be an adult, and I couldn’t make that transition.

All of a sudden, I used up my student deferments and found myself in the Army, which was a shock, but was probably a good thing.8You hear stories of people who encounter something that really brought them to the right place in their lives, and I think I could be numbered among those, because it gave me a sense of being cut off from all of the opportunities I took for granted. When I finally got back I was so craving the things that had been stripped away that they became a pleasure rather than a distraction. That’s when I really started to become more productive. I got back to ArtCenter and all of a sudden was able to say, “Fuck it. I’m just going to do what I do. This is interesting to me. I’m feeling energy from the place I’m in. I’m just going to think about a project, do that, then do another project, and go on like that. That’s all my life needs to consist of.”

I got to a certain point with my training as a designer when I couldn’t resist making fun of it. The Cadillacs with the huge fins that now seem funny to everyone, in the late ‘50s that was taken very seriously. There were all these people sitting at drafting tables in Detroit, playing with pictures of airplanes and trying to combine them into cars—it’s just silly. It seemed like the whole thing was absurd and I couldn’t resist tampering with it, which did not go over well at ArtCenter. I was actually kicked out, ostensibly for this half car, half man project I designed. It was a car in the human scale that gradually morphed into a human being. The top part of it was the car, and the lower part was a human being from the waist down and crouched down on one knee, with the other leg up, like a dog peeing. A map of Detroit was the target of the stream coming out. But I made it quite accurate. The car part was a very realistic child’s pedal car I found at a thrift shop that had these wonderful headlights, a big grille and bumper, and it was very much in the proportions of a real car. The human part was anatomical and also quite believable. I had done a lot of life drawing, so I was doing it in this traditional perspective.

Pippa Garner, Kar-Mann (Half Human Half Car), 1969, fiberglass, urethane foam, metal, paint, wood, astroturf, and other materials. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

The day the project was due was also the day of the commencement address for the graduating class, which happened to be from the chief designer at General Motors. GM was a big funder of ArtCenter at the time. I had a good friend who was my roommate, a German guy who was an advertising major. We went and paraded my design through the whole school. As we got to the front lobby, it was just after the commencement address had finished, and the GM people and the school administrators were coming in on one side as we came in on the other side carrying the half car, half man. The school director freaked out and ran up and said, “Cover up the obscene part.” And my German friend, without cracking a smile, took his sport jacket off and put it over the car part. It was an incredible little scene, and they basically said, “You’ll never graduate.” So, I was asked to move on after that.

DM: Car culture has fueled much of your work, and it seems like you have a love-hate relationship with automobiles…

PG: When cars first came into existence, they were nothing but a luxury, a novelty originally, because only rich people could afford them. When Ford’s mass production came along and suddenly 25 Model-Ts could be produced in a day, they were affordable, but still nobody wanted them. Because even if they were cheap, what are you going to do with it? The infrastructure had to be there, so that meant the car basically created its own need. You know, nobody knew they needed a car until suddenly the thing existed and they wanted to go places in it and have entertainment and maybe live outside of the cities and it made everybody think, what could we do now?

DM: It’s hard to think of Southern California without thinking of cars, and how they’ve transformed the landscape.

PG: Yes, because there was nothing here but desert. There still isn’t, in a way. It’s a place that to me feels completely unresolved and unsustainable. I found that inspiring because it doesn’t have a structure, so you can create. You can mix it up and play with it. It’s like a game that has a lot of little parts… The way California evolved was interesting because the northern part resembled a more traditional city environment that was also more expensive and less accessible. L.A. was the sloppy end of that—you could do whatever you wanted in L.A. and that didn’t exist anywhere else. In the ‘30s, apparently, there was open country between Beverly Hills and Hollywood. It was all these little communities in the desert and nothing was connected. People came without any plan and threw together a house. It seemed to attract a lot of people who were a little eccentric, you know, any person who might feel trapped in the culture of Pittsburgh or Detroit or someplace. More than any other part of the country there was a community here of people who just couldn’t fit the normal culture. I guess I sensed that, and it was a comfort for me because I was one of those odd people.

Pippa Garner, Nouveau Riche, n.d., pencil on paper, 8.75 x 11.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

Pippa Garner, Car Guy’s Aromatherapy, n.d., pencil on paper, 8.75 x 11.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

DM: Around what time did you become fascinated with pedal power and start cycling around L.A. instead of driving?

PG: I took a photo course at ArtCenter and got really into that, but I also became interested in cameras when I was in Vietnam because you could buy cheap Japanese camera equipment there for nothing. It was Nikons that were really popular at that time, and I was fascinated with the technology. I started carrying a camera with me everywhere when I was back in L.A. But I’d be driving and see some weird thing that somebody had done to their house or car or something and think, “I’d love to shoot that,” but then it’d be gone by the time I was parked and everything. So I was in a thrift shop somewhere and saw this folding bicycle. I thought if I was cycling around with my camera and saw something I wanted to photograph, all I’d have to do is pull up, take the picture, and go. I bought the bicycle for 15 bucks and started using it for transportation instead of a car… It was cheap and free and I was getting fit in the process of starting this amazing photo series, so I just kept doing it. I never really went back to driving after that.9

DM: Those photos led to your first work for West magazine. Can you talk about your work there with Mike Salisbury, and also the Car & Driver column that you had?

PG: West was interesting because that was the first magazine gig I had. I had a job for a while, after I got laid off from Art Center, at a toy designing firm in Playa Del Rey. One of the designers there said, “You should take your drawings and stuff down to West,” because they had a reputation at the time as a really progressive Sunday magazine. Mike was using a lot of unknown local artists. They paid you a whole lot, and right away. I was skeptical, but I went down there with a portfolio and it worked out—I first got a couple of drawing gigs. Then there was a feature they wanted me to do on recycling, which I think was about when the term was invented. Mike said, “Come up with an idea for a cover,” and hooked me up with a photographer and a big studio in Hollywood, and I did just that. I built the whole thing myself, went to a junkyard and got the parts and set it all up there. That was a huge piece, and it won an art & design award of some kind. After that, more and more work came my way. I was in the right place at the right time. A project like that wouldn’t have worked at another time, and it’s kept me going.

West didn’t last that long. It was a couple of years, then it was considered too avant-garde. The L.A. Times dropped it for a typical conservative Sunday thing, so Mike was out of work. He went and became an art director at Rolling Stone. I actually worked for Rolling Stone for a while when he was there. The other thing that came up was Los Angeles magazine, which was independently owned at the time. They’d seen these things I’d been doing and asked me if I would do the last page in the magazine. It was sort of a riff on life in L.A. That was the first regular gig that I got out of a magazine, for a year or two. Then Disney bought it and fired everybody. I was out of that gig, but one of the editors of Car & Driver, which is in Ann Arbor, had been watching, and he asked if I would like to do the same thing for Car & Driver, which was great because it started almost immediately. I don’t think I missed a month without work and they paid a lot more. It was in the mid ’90s when I started that and lasted for 15 years, until 2005 or 2006.

Pippa Garner, c. 1990s, pencil on paper, 14.5 x 11 inches each, in Car & Driver magazine. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

DM: Tell us about the backwards car.

PG: Well, I had this idea that my fascination in life would be car styling. I’m lucky for having been born in 1942. Consumerism didn’t really get going until the ‘50s—there needed to be more advances in making things cheap and so forth. All of a sudden, here’s World War II, which was a hideous thing, but by the time the war was over in 1945, the manufacturing industry was born, which meant producing commercial products. Advertising was pretty naïve prior to that, too. But suddenly, the idea of in-your-face advertising became relevant in the early ’50s. They said, “We’ve got to sell things that people don’t know they need. Let’s do it, and then we’ll do it more!” Then we had this huge transition to consumer culture. The term “consumerism” didn’t even exist until then. “Consumer” did, but there wasn’t an “-ism”—it wasn’t a lifestyle as it became in the ’50s. That was just when I was clocking in as an early adolescent. I absorbed all of that.

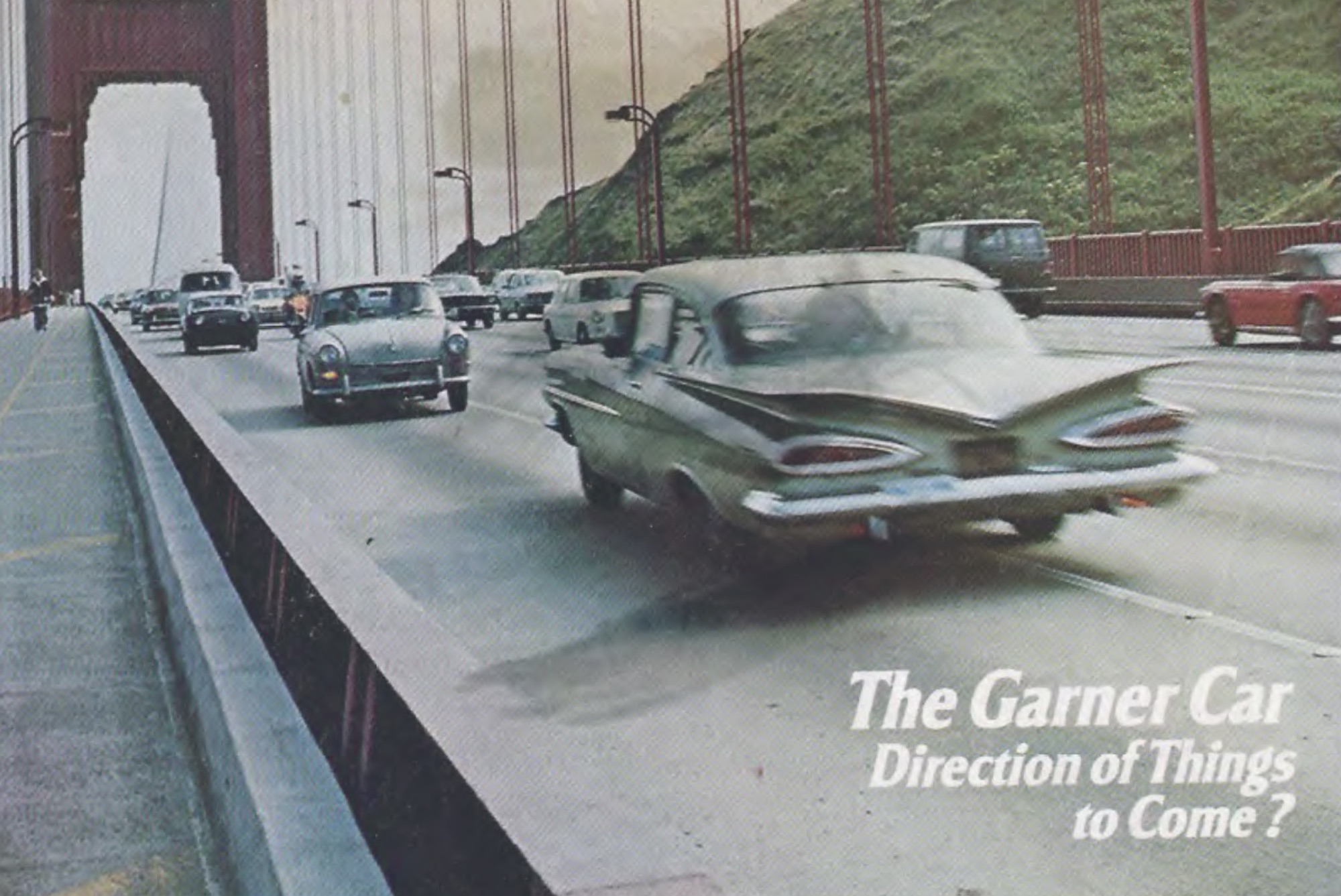

Again, my timing was perfect to get set up for what I was going to end up doing. The backwards car, somehow I thought it was funny, the whole idea of trying to make cars look directional. One of the cliché advertising phrases was, “Looks like it’s moving when it’s standing still,” so I had this idea to do a backwards Cadillac. I thought, “If you turned it around, wouldn’t that be absurd?” I went with a friend of mine to this used car lot where they had a Cadillac convertible with the fins. I said, “Just go over there and don’t turn around until I tell you.” I didn’t tell him what I was going to do because I wanted to see what his first reaction was. I went in and crouched down on the right, turned the wrong way around, so it looked like I was driving the car backwards. Then I told my friend to turn around, and he literally fell on his face with laughter! I said, “I’ve got to do this. It has to be done.” But then I realized, “Okay, I can’t do a Cadillac because I bloody can’t see over the fins.”

I went through all the cars that I could think of. Finally, I settled on a ’59 Chevy because they had the same directional “looks like it’s moving when it’s standing still” look, but the fins were flat. The trunk was flat, the fins were sort of dished in on the sides of these oval exclamation point-looking tail lights. Then I realized I could see out of it. It wasn’t going to be an obstruction. I did the drawings of the backwards car and pitched it to several magazines and Esquire took it. They wrote a little piece to go with it explaining that one thing people take for granted is driving. You just get in your car. You turn your brain off. You put a foot on the gas and that’s it. But what would something completely unacceptable be like? The shock value would be interesting, or maybe it’d be stupid because it might be dangerous, but again at that age, I wasn’t too worried about that. They picked it up right away for $1,500. That was enough that I could get a used car and a parking garage near the Marina in San Francisco. I managed to work a deal out with them—I said, “Look, it’ll take me a month.”… That was all documented by Jeff Cohen, a photographer in New York who was assigned by Esquire at a big studio in San Francisco.10

Pippa Garner’s backwards car in “The Garner Car: Direction of Things to Come?,” Esquire magazine, November 1974. Photo by Jeff Cohen.

Detail view of Pippa Garner’s backwards car in Esquire magazine, November 1974. Photo by Jeff Cohen.

DM: It seems amazing that a print magazine had the resources for a project of this scale. Earlier, you were talking about feeling like there was something declassé, or less than, about working on these commercial projects in the eyes of the fine arts world proper, but there’s something so subversive about the work you did. You were very aware of operating in the mass media and it seems like that’s something you really strived for. Were you able to get done what you hoped in that medium?

PG: Each thing I did would give me a little bit more leverage. Especially after doing something like that, they figured, “Okay, he pulled that off. We’ll just trust you to do anything you want.” I had a lot of liberty. Again, being able to do something like that for $1,500… It was the total cost of everything, the car itself, renting the space and everything I needed. It wasn’t actually expensive to do it. I had to do a lot of calculating to figure out how to anticipate the way to cut out the trunk on the floor so that when the body was lifted and turned around, it would fit around the engine and the radiator. I had to do everything by hand—go in there with a hacksaw and cut it all out, that sort of thing. Then the same with underneath, taking off all the attachments to the body bolts, measuring where they hit the frame at the other end when turned around, and if I needed to put a spacer in there or what to make it level. I was very lucky I had it just about right on almost all of those calculations.

When we got the body turned around backward, that was a big party. After I had gotten the thing all ready to go, it was like, “Okay. Somehow or another, it’s got to be lifted up, turned around and moved back. How can we do it? Humans.” I remember in the army there were a couple of situations where they wanted something moved. One was a big tree trunk when I was in basic training. It would have taken a lift device of some kind to move it. This sergeant got the whole company lined up completely around the edge of this tree trunk and commanded, “Heave!” It was all human beings only and the thing came right up and we were able to move it.

I realized I could probably do the same thing with this car if I could figure out the maximum number of people I could get around it to lift it up and turn it around. The party consisted of refreshments, including alcohol. We were having a good time and then I got them all lined up, worried like hell that they wouldn’t be able to do it for some reason, but sure enough, when I gave the command, up it came. Once that was done, there was still a lot of work to get it right. I had to redo the controls, all sort of things, but at the same time, I knew I was going to pull it off. It took another couple of weeks, then I drove it out of there.

Pippa Garner, Backwards Car, performance documentation, Bay Bridge, San Francisco, 1973. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

DM: After witnessing human power in Vietnam, and using that experience to create the backwards car, it seems to lead up to the pedal cars you’ve been doing since you moved to Long Beach. How did those start?

I couldn’t find anything so that’s when I started to seriously work on building and designing a pedal car that was safe and as useful as a bicycle, but wouldn’t need the balance of a bicycle, and would have utility and protection from the weather, and visibility so people could see you. I then spent several years in Santa Fe. It took me a while, but I finally got two or three different pedal car designs. In particular, one I’m still using for transportation that’s got over 35,000 miles on it in about 18 years of riding. It’s not that impressive when you think of it, but I haven’t had a scratch since then. It’s safe. It does what I need to do. It’s fun to ride. It holds other kinds of stuff.

I was always fascinated with Burning Man. So, when I was in Santa Fe I managed to track down this car somebody had bought, a very small ’72 Honda sedan, for a couple hundred dollars. It was the first time they imported Hondas and it was very little. The body was perfect on it, but it didn’t run. The engine had been taken out. I went back to the sketchbook and made drawings of how I was going to do it and what it was going to look like. I talked to the editors at Car & Driver about possibly taking it to Burning Man, so they gave me some money in advance and I went ahead and constructed it. It was a two-passenger… Both the passenger and the driver can pedal it—I had gotten totally into recumbent bikes and so I made it recumbent.

Pippa Garner, World’s Most Fuel-Efficient Car, 2007, 1972 Honda 600 converted to be human-powered, 60 x 52 x 120 inches. Courtesy of the artist and STARS, Los Angeles.

So, I built this thing and it worked well around Santa Fe. I took it to Burning Man in 2006 for 10 days. A friend of mine and I rented a U-Haul and put it in the back and lived in the U-Haul up there. During the day, I was on assignment from Car & Driver to pedal around and photograph bizarre vehicles I saw and interview the owners. That car now is in the Audrain Automobile Museum in Rhode Island.

DM: You’ve spoken before about nostalgia, memory, and the utility of looking back, but not wanting to be captured by the past—wanting to always be moving forward. What are your thoughts on nostalgia and legacy?

PG: Well, all the things I’ve been through, from 1942 forward, are like sound bites of knowledge. They’re resources just filed away that I can play with. I can pull this out and mix it up with that, or I can just use it randomly and whimsically. I don’t want to look back. I just want to use these resources. One of the advantages I have now is that I’m really immature in a lot of ways. I never did anything to grow up. I never owned any property or had any kids or worked in a situation where other people were under me or any of that. It’s all just been completely solo. But suddenly now, this machine that I live in… that’s one of the devastating things that I’m having to deal with now because I’m in a holding pattern—I’m trying to break through this and get back. It’s like there’s another version of me that’s floating around right next to me and I can’t get them together. It’s like being dead and alive at the same time.

Pippa Garner, “Immaculate Misconceptions,” installation view, JOAN, Los Angeles, 2021. Photo by Josh Schaedel. Courtesy of the artist, JOAN, Los Angeles and STARS, Los Angeles.

Pippa Garner, “Immaculate Misconceptions,” installation view, Verge Center for the Arts, Sacramento, 2022. Photo by Scott Duncan. Courtesy of Verge Center for the Arts

When I look in the mirror, I think of myself as kind of an appliance. I didn’t ask to be six foot two, honky, genetically male, middle class, any of that. It’s just how I landed on earth. And so in a sense, I’m detached from my physical entity as it’s just another thing that I can use and have fun with.11 My sense of the past is fragmented like that. I don’t feel like I have a past, myself, really. I can read about the past and I can cite specific events and interests and circumstances that I’ve been in, but what I want to do is filter something new out of that. Especially now, this age we’re in is so transitional. It seems to me maybe all ages are and it goes on forever, doesn’t it? We’re all just one frame of an endless film. What happens is irrelevant really, whether I die tomorrow or have another last blast of a couple years and can turn out some more things that are in some new way mixing my experiences and my interests. It doesn’t really make any difference. I’ve already put in 80 years, which is an awful lot for a cancer patient. So I’ve been cheating time.

To get this much creative time out of a system that’s already got a great defect in it… I think I shouldn’t ask for more, but of course I do. A couple more years would be great. I want to play with things and mix them up and I don’t want to have wisdom. Wisdom seems heavy, like an anchor. Sound bites of knowledge are what seem more appropriate to me—a little flash here and there… And again, a lot of it doesn’t work. A lot of the stuff I’ve done is terrible, but it’s just been a long time, so I’ve managed to come up with a good range of things that were successful. But there’s been an awful lot that I either trashed myself without showing anybody or that was somehow inappropriate or something didn’t work. That’s just the way everything works.

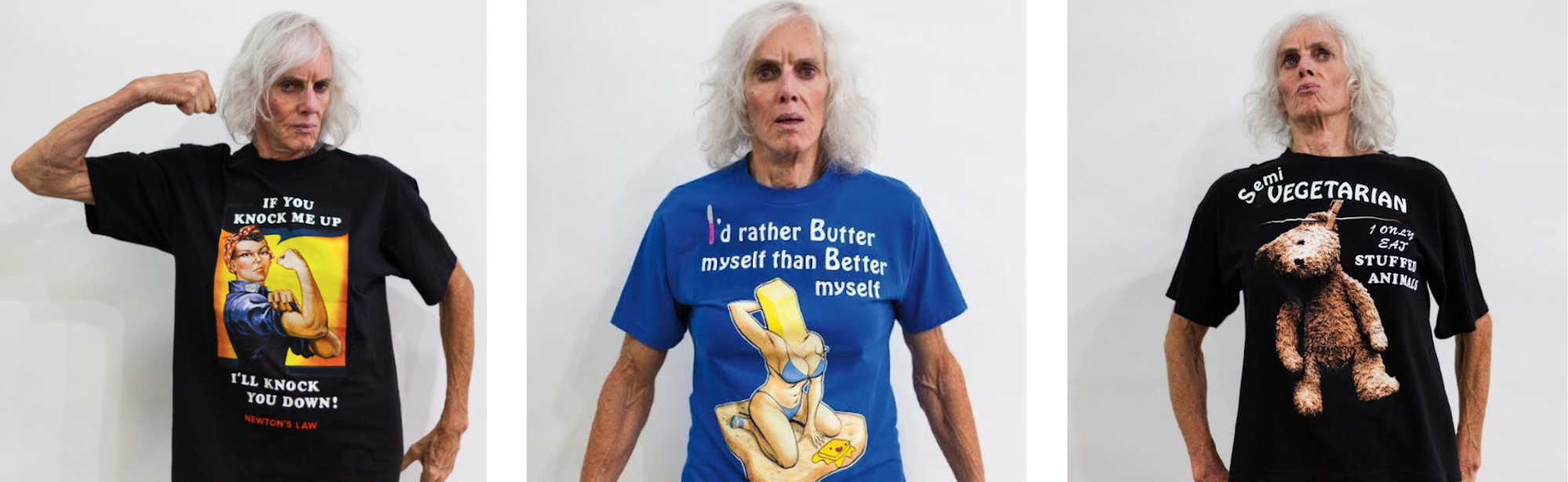

Pippa Garner, Shirtstorm series, 2017, mixed media on t-shirt, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Redling Fine Art.

DM: In lieu of wisdom, is there some parting knowledge or advice you think you could impart to young artists and students, in terms of remaining an artist for the long haul?

PG: I don’t know. I don’t feel much different usually when I’m talking to people that are younger. Most friends of mine are in their thirties. I never have a sense of being a senior to them, really. I just have a lot more knick-knacks, fragments, pieces of stuff floating around in my head. So I don’t see it as much as a transition from one generation to another. I don’t know—I never have any sense of having achieved something that I could pass on as it was.

DM: Well, I think it’s there whether you’re aware of it or not. It’s not something that you can help but possess after this much time.

PG: I might try to sabotage it if I knew that.

DM: I know the feeling.

PG: Yeah. Get rid of it and get back to zero again. One of my themes is that nothing exists that wasn’t there in the first place.