Mike Kelley: The Fine Art of Dropping Out

by Anthony Strain

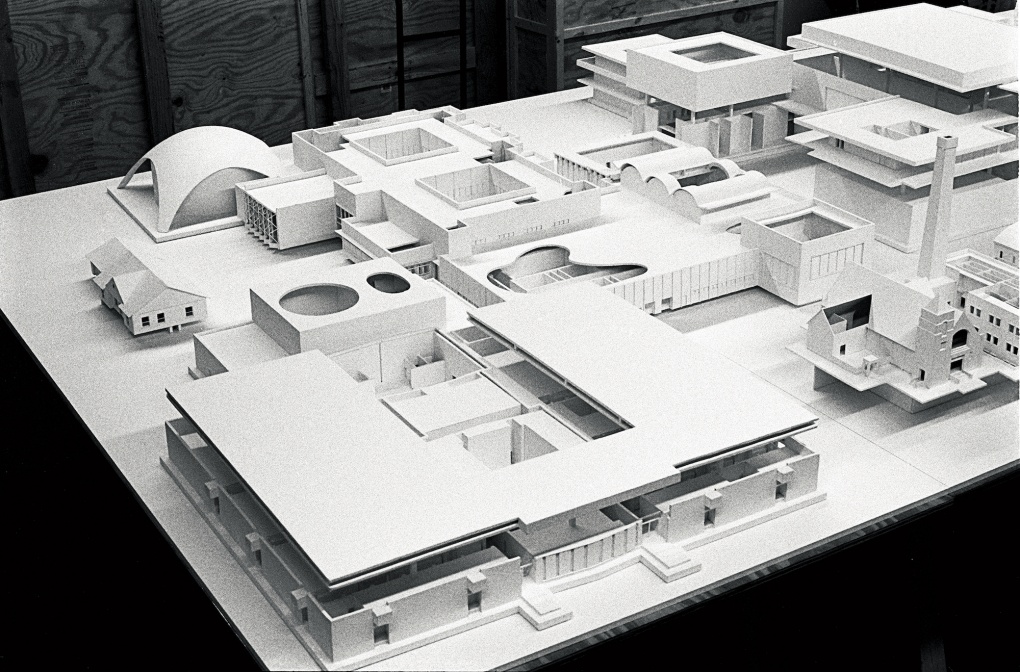

Mike Kelley, Educational Complex (Detail), 1995, painted foam core, fiberglass, plywood, wood, plexiglass and mattress, 57 3/4 x 192 3/16 x 96 1/8 in. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

1.

Mike Kelley’s interest in architecture peaked in 1990, when he collaborated with Frank Gehry on a design proposal for the offices of the Chiat/Day ad agency. Reflecting on the strangeness of boxes—miniature replicas and exhibition spaces—Kelley understood the assignment as a joke and visualized a boardroom window looking into a copy room, with crude cartoons on every office wall. Chiat/Day didn’t go for it, obviously, but Kelley saw the utopia of it all and built a full-scale model of the space anyway: Proposal for the Decoration of an Island of Conference Rooms (with Copy Room) for an Advertising Agency Designed by Frank Gehry was presented in the Helter Skelter exhibition at MOCA, Los Angeles, in 1992.1Borrowing heavily from Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, he imagined sites romanticized for their intimacy or whimsicality, like walk-in closets and bedside tables, as repositories for the unspeakable. Such a data scrape set up one of his most famous works, Educational Complex (1995), which reconstructed every school he ever attended, plus his childhood home, as a tabletop architectural model, in fiberglass and painted foam core.2With its intentionally failed idealization of childhood, Educational Complex is not a sculpture of love or fondness; it’s a statue pulled down with chains. Throughout a multivalent career, Kelley never took aim at a specific institution, but he was against most of them, in the cordial style from which cult heroes are born. Gentle derision appeals to the eye and the mind. To paraphrase Pascal: Kelley was not content to kneel down and move his lips in prayer, because that is not what belief was to him.3Many of his artistic acts show that faith and reason don’t need to be renounced wholly; they can be simply dropped out of. Which is much different than flunking.

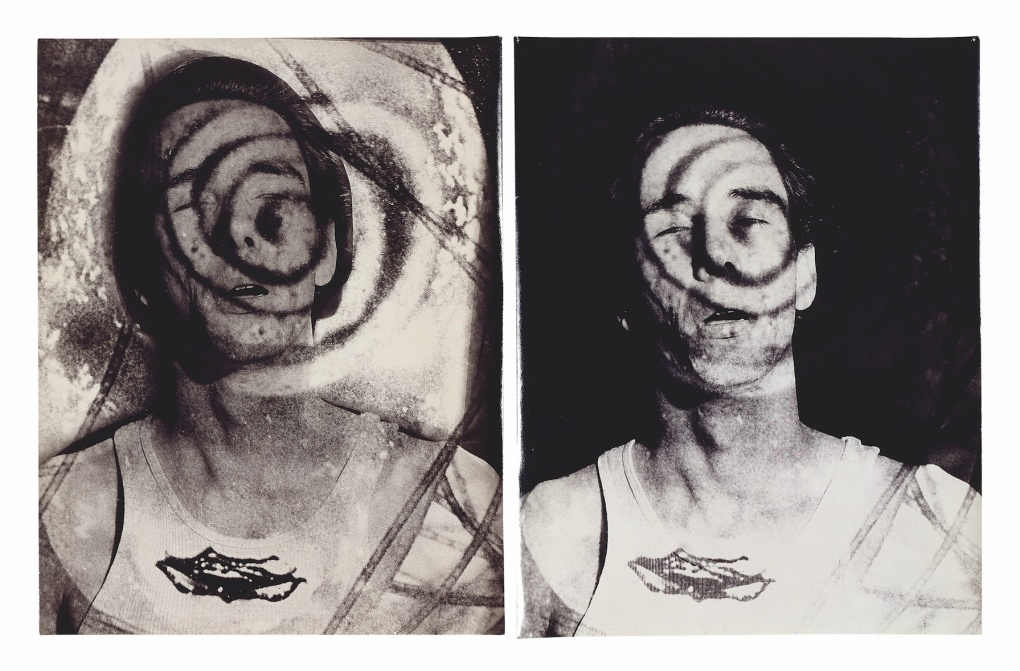

Mike Kelley, Untitled Photograph, 1982, from Confusion, 10 x 8 in. each. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

2.

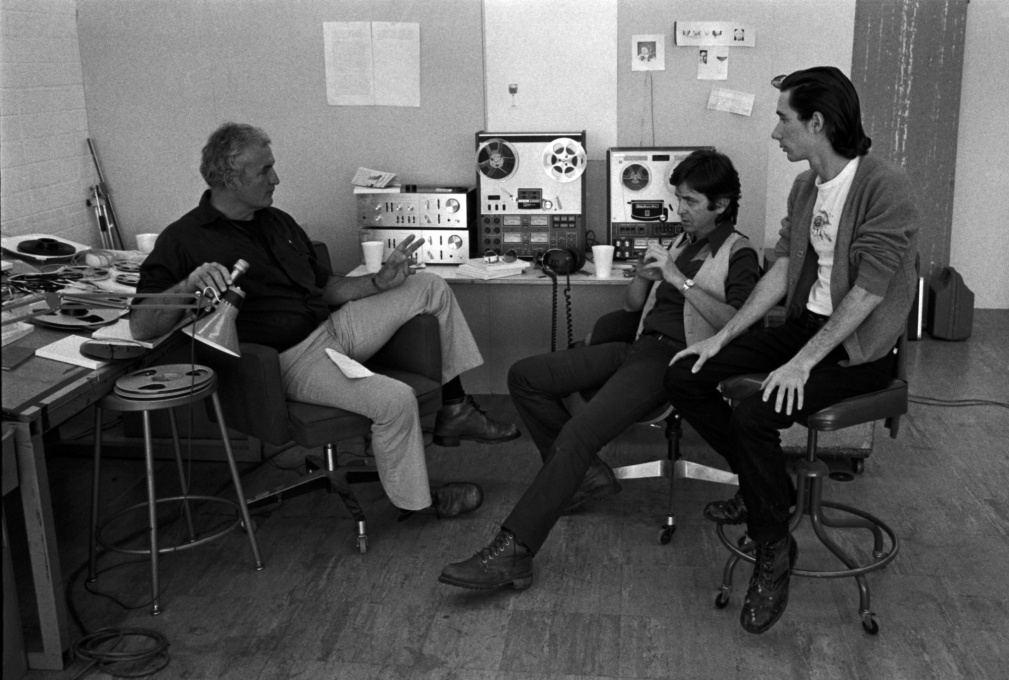

Since I never really went to school, you could call my relationship with formal education adversarial. During my first and only semester of art school, an instructor of mine in the advertising program was quick to congratulate me on my “out of the box” thinking—that was the first red flag, and the next was that every student but me had a spectacular budget for their mocked-up beer or aerospace ads. It’s no albatross (maybe one the weight of a hummingbird), although you could reliably say I have an educational complex4of my own that no amount of autodidacticism can relieve. For some people, school is everything: a structure by which to appreciate progress and to be appreciated. For other people, it’s just a phase to get through, or an ordeal to endure. Kelley’s catharsis happened as an art student enrolled in the University of Michigan, where he embraced and then tired of gestural Pop painters like Robert Rauschenberg. After completing his BFA he left Ann Arbor for the MFA program at CalArts, where dissension against institutional malaise was the prevalent mode, brought on by overreliance, through the mid-twentieth century, on the formalist rigors of art school figures like Hans Hofmann. This newer picture of art education was a slow fever, and conceptualism was the icebreaker. Reconfiguring the teacher/pupil vector was Michael Asher, who joined CalArts faculty in 1976, in time to teach Kelley.5But resistance to being mapped out via syllabi, prerequisites, and curriculum can make for a frustrating student, from the teacher’s perspective;6the ever-shrinking contours of the map become an argument for self-erasure. Comply or disappear, as writer and educator Jaymee Martin put it.7Howard Singerman, in a 1999 critique of MFA programs, used the phrase “assignment of un-mastery”8—essentially, what does the teacher want? (Who cares!)

Doug Huebler, Tim Silverlake, Mike Kelley, 1978, CalArts, Valencia, CA. Photo by Frank Foster. Courtesy of CalArts Institute Archives.

3.

With all his allusions to repressed memory syndrome, facetious or not, and the fact that he died by suicide, at some point Kelley’s work came to be discussed as “trauma art;” such a category minimizes his fascination with moods larger than his own. In 1998 and 2002, Kelley made the Missing Time Color Exercises, a painting series which echoed the Budd Hopkins’s UFOlogy bestseller, Missing Time: A Documented Study of UFO Abductions.9In light of all this, I wonder what he’d think about QAnon, the defining mythopoesis of our age, whose fans re-cast the Missing Time phenomenon of UFOlogists with wealthy elites and elected officials as abducting, probing aliens. If you prefer the cynical view of QAnon, it’s a petit-bourgeois concern of people whose panic is AstroTurfed—many of them are millionaires, at least on paper, and they have too much free time. They delight in either belaboring the point (Hollywood, DC, and Silicon Valley are actively plotting our destruction) or, in the case of Trump Won, missing it altogether (every election is kind of rigged, as is all of democracy). Althusser defined ideology as “the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.”10Some adherents to Q think the United States has been a corporation since the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871 and use that to say the law doesn’t apply to them. Ambiently and anecdotally, the animus of QAnon is the purée of American pseudo-entrepreneurs, the restless id of small business, the deep need to be a CEO: if you, say, own a pool cleaning service in Gatlinburg or sell jet-skis in Eureka Springs you’re more likely to get redpilled, for some reason. Those aren’t email jobs, but they’re still kind of weird and fake.

Paranoia can be an attempt to eradicate or soberly react to history. One of Kelley’s aesthetic monuments was the 1980s McMartin Preschool child abuse scandal; Educational Complex is largely based on it. Like the deposed children who dreamed up depravity in hidden corridors beneath their daycare, Kelley restored vanished buildings with the touch of the recently blinded, or like an actor reciting lines the moment they start to forget them.11Messing around with repressed memories, he isolated “institutional or general sociocultural abuse” as a possible trauma.12Conspiracy theory animated Kelley, and he was always a sympathetic viewer. Like any good student of the carnival, he saw no need to aggrandize what was already freakish; that’s something early freak show practitioners misunderstood.13The thrift store dolls and stuffed animals that made Kelley famous were just toys. Outside the vacuum of paranoia, Arena #7 (Bears) could be proto-furrycore or something; inside that vacuum, they exude sinister ketones that can chemically damage your psyche if you look at them too long. Stuffed animals are really good at showing the twilight between facts and feelings. If it can be hugged, it can be loved, or at least that’s what the toy companies got rich on.

Mike Kelley, Arena #7 (Bears), 1990, found stuffed animals and blanket, 11 1/2 x 53 x 49 in. Photo: Douglas M. Parker © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

For real heads, smoke from the McMartin trial’s fires still loiters in the lungs. The case of alleged sexual abuse at the school broke U.S. court expense records in the 1980s, lasting a total of seven years, without making a single conviction. Children at the Manhattan Beach preschool became star witnesses, and their increasingly sensational testimony is no less intoxicating once you realize not a word is true. They talked of witches, of being taken up in hot air balloons, of pet rabbits and turtles being killed, of altars and Satanic orgies at car washes, of being flushed down toilets into secret rooms beneath the school. Coerced by adults flying on moral panic, most of the deposed children started free associating just so they could be excused. What you say is what you are, you’re a naked movie star was just a nursery rhyme that accidentally ricocheted.14One child later remembered his mother singing it to him to jog his memory of, allegedly, being photographed naked by Satanists, and who knows what else! Logically of its time, the circumstantial pomp and billowing illogic of the McMartin proceedings acquired a campy following later on. “Naked Movie Star” is the glassiest instance of kitsch ever produced in our menagerie of a legal system.

The former McMartin Preschool decaying among weeds, April 14, 1988, Manhattan Beach, CA. Photo: Alan Hagman / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

School founder Virginia McMartin, 77, outside courthouse. Photo: AP Images.

4.

I don’t believe Kelley would tolerate many iotas of Q, were he alive, but its reliance on paranoid ideation, stocked with more questions than answers, would interest him for the same reasons he moved on from stuffed animals—namely, why is everyone so obsessed with trauma? Why is the only acceptable narrative clotted with horror? Parul Seghal covered this overreach in her “trauma plot” piece for the New Yorker: “(the trauma plot) flattens, distorts, reduces character to symptom, and in turn, instructs and insists upon its moral authority.”15A critical spoke in the ever-turning wheel of QAnon also rolls across whole online battlefields: that basically everyone is a pedophile. Reading even little swatches of discourse, which is more than I recommend, you’d think that all rich people know is tax shelters, shell corporations, and sex with minors. For the rest of us above a certain age, watching Euphoria (early media for which Kelley’s oil on canvas Crying Horse (1990) oddly looks like) is proof of prurient intent.16As journalist Walter Kirn put it: “The audience for internet narratives doesn’t want to read, it wants to write.”17That’s dropout behavior. Also, people want cases to solve and will make up their own if necessary. Kelley abandoned his Arenas era when his work started being frequently misinterpreted as infantilism or pedophilia by the kinds of armchair archaeologists who don’t stop digging until a full-size whale, black with tar, emerges dripping from the pit. Kelley said: “I found that it was impossible to bypass the audience’s tendency to project onto stuffed animals. Viewers invariably desired them to be pseudo-children, and were unwilling to give up this belief.”18

Crying Horse, 1991, oil on canvas, 50 x 37.8 x 1.75 in. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Using this rationale, the childlike desire to reality-shift drives the Q fan, who then, as a child or child actor, considers journalists or tech oligarchs or whoever else to be the “adults” trying to stop the game. Q’s “Save the Children” spinoff, its ministry of child sex trafficking as it were, took off in 2020, with street protests, attracting a younger crowd who probably just wanted to get out of the house like everyone else. In the Q reality, of which former president Trump is the unwitting starchitect, there is no memory—only repression. The DSM-V has rebranded it dissociative amnesia, or “retrospectively reported memory gaps.” The instinct to build an entirely new political identity often means forgetting what you know. Kelley:

“A major cultural shift has turned the homey into the uncanny. The old-fashioned ‘family romance,’ where the fantasy parental replacement is with figures better than your real ones (my real parents are royalty), has been replaced with its opposite (I suddenly remember my parents are members of a satanic murder cult). The treasured past is now the albatross around your neck. Perhaps this is the return of modernist progress, of the desire to destroy the past, yet all the while wallowing in it.”19

McMartin Preschool bulldozed as parents watched, May 29, 1990, Manhattan Beach, CA. Photo: Al Seib / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

5.

The edifices Kelley reconstructed for Educational Complex are as follows:

1. Kelley residence, Westland Michigan

2. Harvey Street Kindergarten, Westland, Michigan

3. St. Mary’s School, Wayne, Michigan

4. Stevenson Middle School, Westland, Michigan

5. John Glenn High School, Westland, Michigan

6. Old Art and Architecture Building, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

7. Art and Architecture Building, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

8. California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Valencia, California

The last of these is the largest, maybe because it was the freshest in his mind, and includes a kind of model within a model: a replica of the CalArts film school underneath.20It’s that underness, beyond interiority, that brings the work closest to Freud, both in terms of the uncanny and the repetition compulsion. In the world of Educational Complex, filmmakers—both masters and pupils—operate like surgeons in the dreary nethers, cutting up images that may never see the light, watching over and over.

6.

In reality, I was homeschooled. If you live at school, there’s nowhere to hide. Your kitchen becomes a cafeteria and your desk is always in the next room, waiting. I won’t tell you how old I am, but as Reaganist privateers descended into every port, my dad, a public educator, decided public education was a mistake. My mom, who listened to Marlin Maddoux all day, agreed.21The curriculum we used at home was called Accelerated Christian Education (ACE); one of our pastors at the time called it the “Cadillac” of Christian education, in an article for the local paper. Fueled by still-nascent Evangelicalism, if there was an overriding ACE ethos it was to memorize everything and analyze nothing, including Creationism and apartheid. This was an attempt at alchemy by my parents, who were convinced my ability to grow into a Christian adult would be fatally compromised by municipal incubation. What did homeschooling do to my thinking? In pedagogy, rote recall is like a fantasy of knowledge, and merely electrifies monsters of debate, like the ones Ben Lerner curated so vividly in The Topeka School. While I have no notes or even regrets about all this, it’s hard to tell if my aversion to schooling, which persisted as an adult, was really ever my idea. Kelley realized while making Educational Complex that he couldn’t remember enough details from the inside of the buildings, so he left them out. While the exteriors are modeled and elevated, the missing teeth of the interiors are empty and inaccessible, like tabs of dissolved acid.

Mike Kelley, bird’s eye view of Educational Complex, 1995. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

7.

My own personal educational complex would include the following:

1. Strain residence (yellow house, petrified rocks in the yard), 1117 Olive Street, Carthage, Missouri

2. Strain residence (parsonage, probably ramshackle), somewhere off E Highway (?), Doniphan, Missouri

3. Strain residence (duplex, brick on the street side, master bedroom a converted garage), 657 E. 143rd Street, Glenpool, Oklahoma

4. Tulsa Community College (great school…), Tulsa, Oklahoma

5. Academy of Art University (redacted), San Francisco, California

8.

More than nature or culture worship, Kelley practiced a sort of nurture worship, with a fondness for youthful alacrity and a high interest in the nuclear. What Kelley called the Agents of Besmirchment—sexuality, bodily function, crimes against family—are embedded throughout his work. An early video collaboration with gross-out king Paul McCarthy,22Family Tyranny (Modeling and Molding), isn’t viewable in its entirety online, and originally there were six hours of taped content—anyway, all I remember is the eerie refrain: “Daddy come home from work again, Daddy come home from woooooork.”23I haven’t seen anything he did with Raymond Pettibon, but apparently a Jim Morrison video was in the works, with Kelley as Morrison, until Oliver Stone announced his Doors movie. (If there was ever a scatological figure, the Lizard King was it.) Meanwhile, in his psychological study of a minor Captain Kangaroo character, The Banana Man,24Kelley says at one point: “Nooo, don’t shrug me off, I shrug THEM off,” while being carried on someone’s shoulders. He’s holding a sign that says “My Actions.” This video and a larger-scale installation work, Monkey Island (1982-1983), extended the artist’s nurture worship toward the work of Harry Harlow, who in the 1960s researched forms of primate expression and bonding.25Kelley equated Harlow to Tennessee Williams, I guess because both of them feature a lot of absent fathers: “Harlow’s experiments originally grew out of the observation that infant monkeys developed strong attachments to simple cloth pads placed in their cages, in a manner reminiscent of a human infant’s attachment to a security blanket.” Kelley added: “Where is the father in this model?”26

Mike Kelley, Former Kelley Residence, Westland, MI, from Mike Kelley’s series Photo Show Portrays the Familiar, 2001, silver-gelatin print, 16 x 20 in. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

When he wasn’t caretaking, he was busy elevating the deadpan to the realm of the ethereal, as with The Banana Man. Indebted to 1970s absurdism, you see this in the hilariously long or discursive titles, like Test Room Containing Multiple Stimuli Known to Elicit Curiosity and Manipulatory Responses (1999); or Sublevel: Dim Recollection Illuminated by Multi-colored Swamp Gas (1998); or the previously mentioned Mike Kelley’s Proposal for the Decoration of an Island of Conference Rooms (with Copy Room) for an Advertising Agency Designed by Frank Gehry (1992); or his later series Extracurricular Activity Projective Reconstructions (2000-2011), with which he aimed to “eventually make one tape representing each day in a year, and, finally, to restage the tapes live, consecutively, in a twenty-four hour period.”27These stagings, taken from high school yearbooks, recall an earlier defacement phase when he drew a swastika on Abraham Lincoln’s forehead in With Malice toward None: With Charity for All, as part of his Reconstructed History collection. Published in 1990, Reconstructed History features an introduction written by Kelley and printed on fake parchment, in pseudo-colonial style, because “Heroic images thrive on subtraction.”28Adding the swastika, or Lincoln’s blacked-out teeth, wasn’t the premise—Kelley subtracted gravitas.

Mike Kelley, Ahh…Youth!, 1991, set of 8 cibachrome photographs, 24 x 16 in. each. © 2022 Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. All Rights Reserved / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Kelley’s fascination with the familiar, quotidian, or just plain juvenile returned continually to this question of the dropout, of the everyday being more than just scenery to chew out in order to expose the sublime.29The everyday is the sublime, and secession from it is only possible through alien abduction. The way Kelley saw it was: the only escape from the eternal performance of boredom is by turning into pure image, by dropping out. He hinted at this in a conversation with artist Chris Wilder, recorded in January 1998. Kelley disliked alleged UFO photography that occurred in too-scenic vistas, or places “simply too weird-looking for me to accept that something unusual could happen there.”30I don’t care about aliens one way or another, but the possibility of them avoiding the picturesque is really funny to me. Rather than be reduced to images, the highly intelligent and maybe superior race elects to simply not show up.