The Spiritual in Art: An Interview with Maurice Tuchman

by Michael Carter

Michael Carter interviews former LACMA curator of modern art Maurice Tuchman.

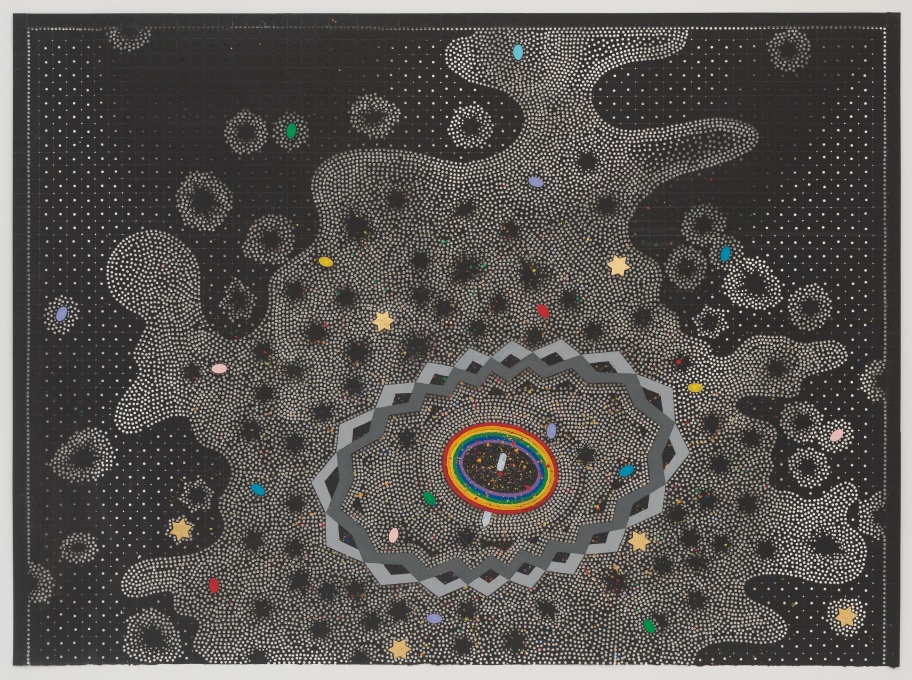

Tom Wudl, Black Nucleus, 1984. Acrylic on paper punch. 47 x 64 in. (119.38 x 162.56 cm) Courtesy of L.A. Louver and © Tom Wudl.

Maurice Tuchman, LACMA’s first curator (1964–1993) of 20th century art, remains an outsized figure in the history of art in Los Angeles.1Known for a legacy both controversial and groundbreaking, his most well known exhibitions—Art and Technology (1971), The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 (1986), and Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art (1992)—continue to resonate today.2It is regarding the 1986 exhibition at LACMA that this interview took place.

The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985 (SPART) was an ambitious effort to reorient the history of abstraction in painting and contemporary art of the preceding 100 years. Starting from a viewpoint inspired by Tuchman’s PhD advisor Meyer Shapiro, SPART made the argument that the avant-garde art of the preceding century could not be meaningfully analyzed or discussed without centering the biographies, philosophies, and discourse of the artists themselves. Controversially, SPART confined this argument to the “mystical-occult” views and spiritual affiliations of the early generations of Modernists in Europe and America. In particular, the scholarship demonstrated the widespread influence of Theosophy and the Theosophical Society: SPART highlighted the many artists who were members—Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Emil Bisttram, etc.—or who were directly influenced by the Society’s members or its theosophical texts, such as Kazimir Malevich, Agnes Lawrence Pelton, Paul Klee, Johannes Itten, and many others.

Amongst the flood of press surrounding the now legendary Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future at the Guggenheim in New York (October 2018–April 2019), I noticed no one was approaching Tuchman himself about the exhibit. It was in fact more than 30 years earlier, in SPART, that af Klint’s abstract works had first been shown since the artist’s death in 1944. I reached out to Tuchman to ask about the exhibition particularly because I was struck by how ubiquitous SPART’s catalogue was among contemporary artists working today; it seemed everyone I encountered owned a copy, its influence wide and ongoing, irregardless of their views of what the scholarship had demonstrated. It was also clear to me that the larger art world, by 2020, was undeniably in progress of a “spiritual turn,”3something like the one during af Klint’s own lifetime.

The following conversation looks more deeply into Tuchman’s motivations for staging the exhibition, his struggles to realize it, its reception, and the continued influence and controversy of “the spiritual in art” today. This interview was initially conducted at Tuchman’s Hollywood Hills residence—the Astral House—in March 2019 and is now being revisited.

* * *

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Michael Carter: How did you first become interested in exploring the ideas underlying much of the most significant early abstract painting? Was this something you had learned of in graduate school, or something you had to discover for yourself? How did you come to realize there was this intellectual gap in the wider understanding of abstraction and its meaning?

Maurice Tuchman: Well, I think it all began listening to a lecture by my mentor Meyer Shapiro at Columbia University. And I think I didn’t know really what to do with it, how to reckon with it. But it was on my mind through my term at the Guggenheim Museum. But I could never get it off the ground. There was no sympathy for the notion among my colleagues at the museum.

MC: What was the lecture, by Shapiro, what was the content of that lecture that sparked this?

MT: It wasn’t the lecture itself, but a throwaway line that did it. It was just a comment that he made that stuck in my mind. And I mentioned it to a few friends, but it received no sympathy whatsoever among colleagues and museum professionals. It was kicked back into my life by the interest of Sue Ellen Anderson, who was one of the docents at LACMA when I started there. She asked me if I was just going to let the idea lie there, and do nothing about it, just let it slide. Which made me feel a bit guilty. It had received such a poor response among the directors and trustees; they didn’t even want to put it on the agenda. So, I had let it slide. But Sue Ellen said, well, try again. And I thought, why not, maybe there would be more receptiveness this time.

So, after years of letting it slide, I tried again, and this time, with a new director and a slightly more receptive board, I was given permission to apply to the NEH and the NEA for research funds. I got enough funding to organize a private symposium with a number of great scholars to lay out the terms of an argument, and this got enough traction with the board for them to consider a preliminary planning phase.

MC: And what was the timeframe from when you first had this idea, to letting it go, to finding something had changed and being able to start planning?

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

MT: Well, it certainly had been 12 years or something like that. I think maybe Los Angeles proved to be more hospitable than New York had been, certainly by the early ‘80s. But I was always insistent in my own mind about not being partisan. That is to say, I wanted to approach this as an art historian, and didn’t want to indicate any particular interest in the subject from a personal point of view. That was very important. Perhaps it was in the nature of the times then to be prejudiced against spirituality as something irrational that couldn’t be taken seriously.

But there was a serious art historical argument to be made. At that time, we were all great fans of the way the history of modernism was explained and elucidated at MOMA. But I believed it was time for a new generation to look at it with a slightly broader perspective and to allow into the narrative things that had been considered unacceptable. For me, the hot wire was the relationship between certain spiritual beliefs and Nazi thinking.4

MC: I noticed that you brought this up in your catalogue essay right away. Your own family immigrated to the States because they were fleeing looming Nazi persecution in Poland during the late 1920s. Do you feel that there are influences, or some kind of connection there?

MT: No, that wasn’t my point so much as a belief that this idea was present and had disallowed any serious consideration of the spiritual as an important part of some modernist artists’ thinking, that to bring it up might contaminate the work with something they were not responsible for. There was a kind of censorship, or inadvertent censorship, because of this perceived connection to Nazism. And I thought that had to be overcome.

MC: This was the prevalent thinking in New York, but you also found that you struggled to find support for your exploration even in Los Angeles. And it was only later, heading into the late ‘70s, that there started to be a cultural shift among the institutions. Ideas of the spiritual were becoming very important to many people at that time, and Los Angeles was seen as a kind of new age Jerusalem in some ways. There was a renewal of interest in Blavatsky; Steiner schools were a growing thing.

Agnes Pelton, Future, 1941. Oil on canvas. Collection of Palm Springs Art Museum, 75th Anniversary gift of Gerald E. Buck in memory of Bente Buck, Best Friend and Life Companion.

MT: I don’t think it was so much a cultural shift, but the fact that I could get serious support from objective agencies like the NEH and NEA. The people around me would say that if you can get a grant from the NEH to study the idea, then we’ll let you do that. And that was successful, so then I was allowed to go for a larger grant from the NEA. And that was successful. It was a step-by-step and very laborious process, with no one really believing in the whole thing except me as an art historian.

MC: But there were other intellectuals working in this area, like the Finnish art historian, Sixten Ringbom, for instance.5

MT: Right. Sixten influenced me and was unique in that way. I probably picked up his book at Wittenborn in New York, and it just blew me away, a whole different way of looking at modern art history. I didn’t know what to do with it for a long time. And then, you know, it came to pass. Once I had some money from one of the grants, the first person I went to see was Sixten Ringbom. That was an unforgettable experience, he was such a wonderful, thoughtful guy.

MC: And I know that at the Guggenheim in the ‘70s there was also Robert Welsh, who wrote about Mondrian and Theosophy.6

MT: Yes, he contributed an essay to the catalogue.

MC: There’s also the Guggenheim’s own history, which is inescapable in this conversation. It’s interesting that if you go to their website there’s now a whole new section about the histories and beliefs of the founders. They actually have Hilla von Rebay’s astrological chart on the site.7

MT: Yes, that history is inescapable. But the show would have happened if I had worked at another institution. The seed of the idea was planted by Meyer Shapiro when I was a graduate student; it came from an academic place.

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

MC: Let’s talk about the show itself. How did you assemble a team to realize the exhibition? How did you find your allies once you had the resources?

MT: Well, it was a smaller department, but there was an associate curator and an assistant curator, and I used them part time and they were, you know, perfectly professional about it. They dealt with it as they would any other project. They did everything wonderfully.

Once the hurdles were overcome in regards to getting support from my own museum director, it was smooth sailing.8Museums and owners of works we wanted were extremely cooperative. It was as if a window shade came up and light came in. No one was resistant any longer about the theory of the exhibition. I think 99 of the 100 items I requested were approved by the museums for loans. This would have been inconceivable just a couple of years earlier.

MC: Were you also able to reach out to art historians from the era, and other curators, for the exhibition catalogue?

MT: Of course, the cooperation from the scholars in the field, as you see in the catalogue, was uniform. Every scholar responded with immediate enthusiasm for writing about it in as objective a way as they wanted to, but they all wanted to cooperate.

Installation photograph, “Spirit in Abstract Art” symposium held in connection with the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, February 23, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

MC: Besides Sixten, who else did you approach to collaborate?

MT: Specialists of modern art history: Welsh who was the Mondrian scholar; Rose-Carol Washton Long, who was a noted Kandinsky scholar; John Bowlt and Charlotte Douglas, pioneering researchers in the Russian avant-garde. And maybe a couple of more inventive ones that I came up with, like Bill Moritz, who wrote about abstract film and color music, and the art critic Donald Kuspit, who brought everything into a contemporary focus.

MC: Well, the fact that these scholars were looking at the metaphysical interests of those turn of the century artists, did that make them unusual for their era? Or were most historians of that period looking at these things in relation to that work?

MT: Sure. I think, in terms of the artists that they specialized in, they were somewhat more sensitive to those interests. And in one case, I asked an artist who was also a historian to write about Mondrian’s early period, thinking he would have particular insights that the pure scholars might miss—his name was Carel Blotkamp.9[…] I think in that way it was extremely gratifying because it was a breakthrough show, not only because of the content, but because it opened up a new way of thinking about modern art history, and I think that allowed some thoughtful ideas to develop more quickly.

MC: It was groundbreaking, and I feel there haven’t been more shows like it. In some ways the art world has become more conservative.

MT: Absolutely. You know, it has become more conservative. And I think it has to do with the question of sponsorship, and who pays. It’s important to note that this project was not supported by any corporation. That was because we had the support from the County of Los Angeles, up to 93% of our budget. I was able to do this without having to turn to a corporate sponsor who might have second thoughts about the meaning of the show.

MC: Right.

MT: Unfortunately, that’s not the case anymore. Just about every exhibition organized by a major museum needs corporate sponsorship. And I think this definitely casts a pall over idea-oriented shows.

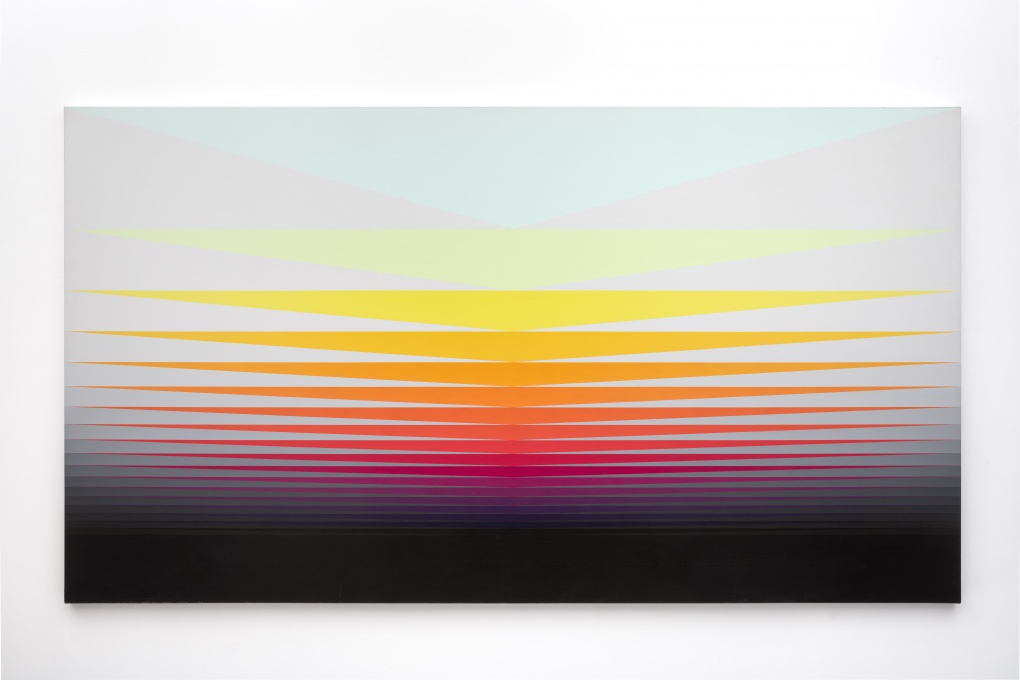

Norman Zammitt (1931-2007), Search for the Elysian Field, 1976 acrylic on canvas 66 x 120 inches; 167.6 x 304.8 centimeters Photo: Gene Ogami © Norman Zammitt Estate, Courtesy of Louis Stern Fine Arts.

MC: Maybe this is a good moment to talk about the relationship between the Art and Technology project and exhibition10 and the SPART exhibition. You’ve said before that these two shows are two sides of the same coin. And the technology exhibition was totally driven by corporate relationships, right?

MT: Yes.

MC: In the past you have said that you don’t think the technology project would have happened if you hadn’t had the idea for the SPART show percolating in your mind, which is a pretty interesting comment if you think about it—most would imagine these two things as completely unconnected. And it’s interesting that the technology project is what has held people’s attention, been restaged, and so on.

MT: Right. It’s the old Yin and Yang theory. I always felt that the one implied a need for a follow-up, its opposite so to speak. That was in my mind pretty early on. It was so difficult to do the first one that I figured the second one couldn’t be that hard. It turned out that it was just as hard, but for different, more practical reasons, not ideological reasons.

But once the spiritual show was in motion, I began to draw up plans for a trio of related exhibits; The Spiritual in Art, outsider art, and then if I had stayed with the museum, I would’ve done a superrealism show. It would’ve been a trilogy.

MC: Can you tell me more about that, about why those things are connected in your mind?

MT: The conference that led to The Spiritual in Art gave me confidence that there was something there that really could be explored in depth, and not just in a single show. I began to consider something more profound, so to speak. I thought of it then as a three-part series, with the second part being outsider art and the third part being superrealism, that was the intention. The second show did happen—outsider art11—but it was received with even more disdain than the first show. And by that time, I had served at the museum for 34 years, so it was time to move on.

MC: So what I’m hearing as you’re describing this process, is that it sounds like you were uncovering strong art historical proofs for relationships between these different modes of art production?

MT: Correct.

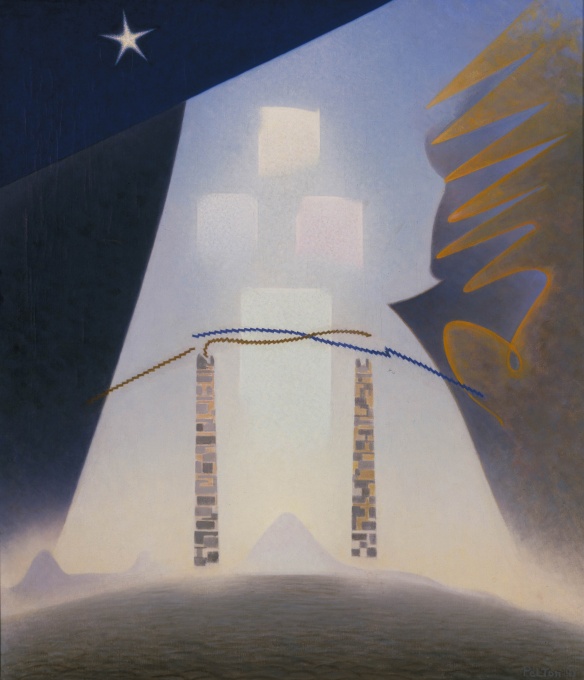

Emil Bisttram (1885–1976), Spectre, c.1940, oil on canvas, 48 x 36 inches/121.9 x 91.4 cm, signed; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

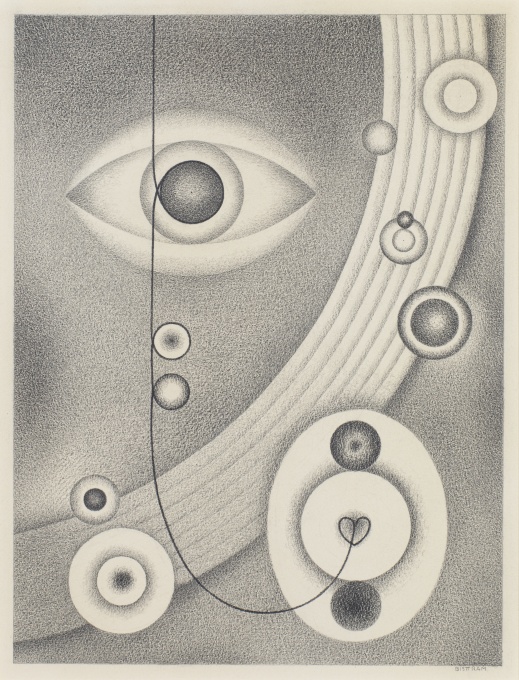

Emil Bisttram (1885–1976), Psychic Sensitivity, c.1940, graphite on paper mounted to Masonite, 23 3/8 x 17 3/8 inches / 59.4 x 44.1 cm, 18 x 13 3/8 inches / 45.7 x 34 cm sight size, signed; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

MC: In your introductory essay to The Spiritual in Art catalogue, you refer to Sheldon Cheney’s writings in the 1920s and ‘30s that refer to the turn to abstraction as related to a growing sense of the mystical.12 And he is making a generational claim that the younger artists are all into these things—occult ideas, spiritual ideas. And then you say that this observation gets totally scrubbed from about 1940 until about 1970.

MT: Absolutely right. The Nazi connection.

MC: Yeah. Do you feel like that’s the only thing that caused that erasure, and that we don’t want to talk about Kandinsky and Theosophy because we think that the Theosophists are responsible for the racial theories that the Nazis espoused?

MT: I think an equally important factor was the prominence of MOMA as an institution defining modernism, and its first director Alfred Barr’s exclusive stress on formalism in laying out the argument. You know, a narrative of action and counteraction, one set of formalist ideas replacing another. There was no room to consider content, and I remember, as a student, being made to feel foolish for raising questions about meaning, that that was merely “subjective.”

MC: Yeah, that seems to have been the programming in art schools in the 1950s and, I think, into the ‘60s—the idea that painting is just what’s in front of you, just the material and the paint on the surface. It can’t possibly point to anything else.

MT: Right.

MC: And to me, that actually sounds like a counterreaction to a generation or two of artists who were saying that the green triangle in the upper left corner means universal spirituality or something like that.

MT: I agree, that was fed and fueled by the romance and ethos surrounding the rise of the new American painting, with most of the artists wanting to stress that there were formal problems that they were pursuing. There were a few exceptions like Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman, but most didn’t want to be associated with anything that had to do with subjectivity or content or ideology.

MC: It’s interesting because we’re now in an era where subjectivity and ideology are massive. It’s all about what cultural subgroup does this artist come from, and what marginalized community are they representing?

MT: Right. Couldn’t agree more.

MC: Related to all this, I think, is the huge outpouring of interest in Hilma af Klint following the exhibition that the Guggenheim mounted a few years ago.13In your conversation with Sam Thorne at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, in 2017,14you pointed to Pontus Hultén15as being the origin of how you were introduced to af Klint’s work, which is amazing considering that Hultén had personally rejected the af Klint family’s attempt to exhibit the work at the Moderna Museet in the late ‘60s.

Installation view, Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future, October 12, 2018-April 23, 2019, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

MT: Well, I think what’s happened is that the bias against anything that smacks of the spiritual has now declined tremendously. Now you could very well be a rational person and still believe that there’s something interesting out there, that it’s worth considering. And I think artists have responded to it because they know when they become artists that they’re not accountants, they’re not adding two plus two is four. They’re looking for something, or why two plus two can become something else altogether. That’s a fantastic thing about life. That’s a fantastic thing about life to acknowledge, you know, the real part of human existence, not something to be disregarded or thrown away.

MC: Af Klint’s importance had been contested since her family first attempted to exhibit her work. Did you have a sense when you included her work in the exhibition that it might impact the importance it’s finding now? I mean, her work has become a sensation.

MT: It took a long time for it to become a sensation, but I had a very strong feeling that showing her in this context was a big deal. But it took a long time, with attention growing in Europe first.

MC: Moderna Museet did a show, the Serpentine Gallery did another, and there were many others in Europe. But after The Spiritual in Art exhibition in L.A. and Chicago, there was only a little exhibition organized at PS1 here in the U.S.

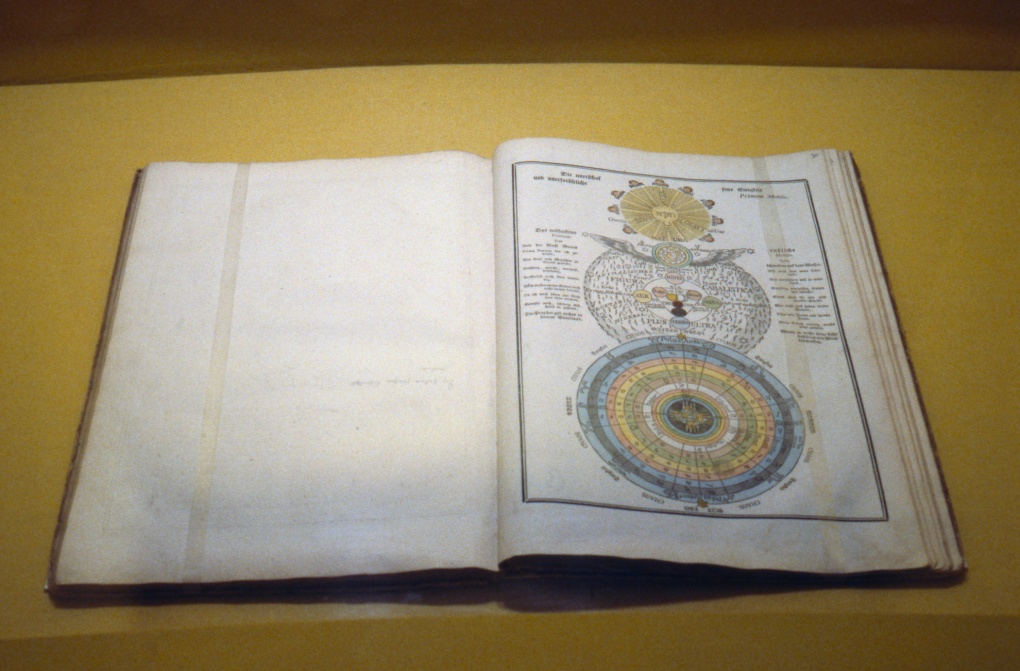

Let’s circle back to the exhibition itself and talk about what else was included, beyond the art. You gathered an array of mystical-occultist texts and books as well, there was a room dedicated to them.

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

MT: Absolutely. And I don’t think anybody had done that before. It was a tremendous draw. All collected in a cabinet, and not on the wall. You can take your time and look at them. People loved that section and bought many more catalogues because we reproduced so many images from these books.

MC: Many of the books in the show, and most of those reproduced in the catalogue, came from the library at the Philosophical Research Society. Can you talk about your experience working with them back in the day? How did that connection come together?

MT: It was simple. It was completely professional, like dealing with any other lending buddy. The fact of their existence probably encouraged me to include that range of books in the show, which wasn’t that common a thing at the time.

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Installation photograph, The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 23, 1986-November 22, 1987. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

MC: Finally, tell me a little bit about your impression of the response to the exhibition at the time. There were a variety of reviews that came out,16and there was also obviously the public interest, which was significant.

MT: It was endlessly gratifying, even though some of the reviews took issue with some of the ideas. I thought it was simply a great success from the point of view of the box office, and from the point of view of scholarly attention. I thought it was a win/win situation for the museum and for my staff and for me. I thought it was great.

MC: It seems the spiritual is no less contentious today than it was 40 years ago.

MT: I agree. I couldn’t agree more.

MC: I’m interested to know what that word “spiritual” means to you. Earlier you said that you did not want to be partisan. But do you think of yourself as a spiritual person, or did you then?

MT: I don’t think of myself as an especially spiritual person because I think that that requires a kind of membership affiliation, which I really don’t want to have. But you can’t live up here and not be conscious of something larger than yourself. You can’t build a house like this and be up here and live here for so many decades without feeling something.

I remember one day in 1968 when Ed Janss, a fabulously rich but thoughtful guy, and an important collector at that time,17came up to me and said he wanted to show me a mountain top that I should live on. So, he drove me up and said, “You know, it is just a modest house, but you should buy it and someday you’ll have the money to build a real house. This is something for you.” No one had ever spoken to me like that, it really affected me… Having been brought up in New York City, I couldn’t believe you could live on top of a hill and see 360 degrees, mountains to ocean. Are you kidding? Who could imagine such a thing? So, the second I saw it, I said I’ve got to do anything in my grasp to buy it. At the time it was $52,000 and I paid it out over 10 or so years. And all that time I had this idea of building something here that would be something special. That took 25 years.

MC: And you associate this experience with the spiritual?

MT: Yeah, I do. I do.

Astral House. Astral Dr, Los Angeles, CA 90046