Artists at Work: Shirley Tse

by Vanessa Holyoak

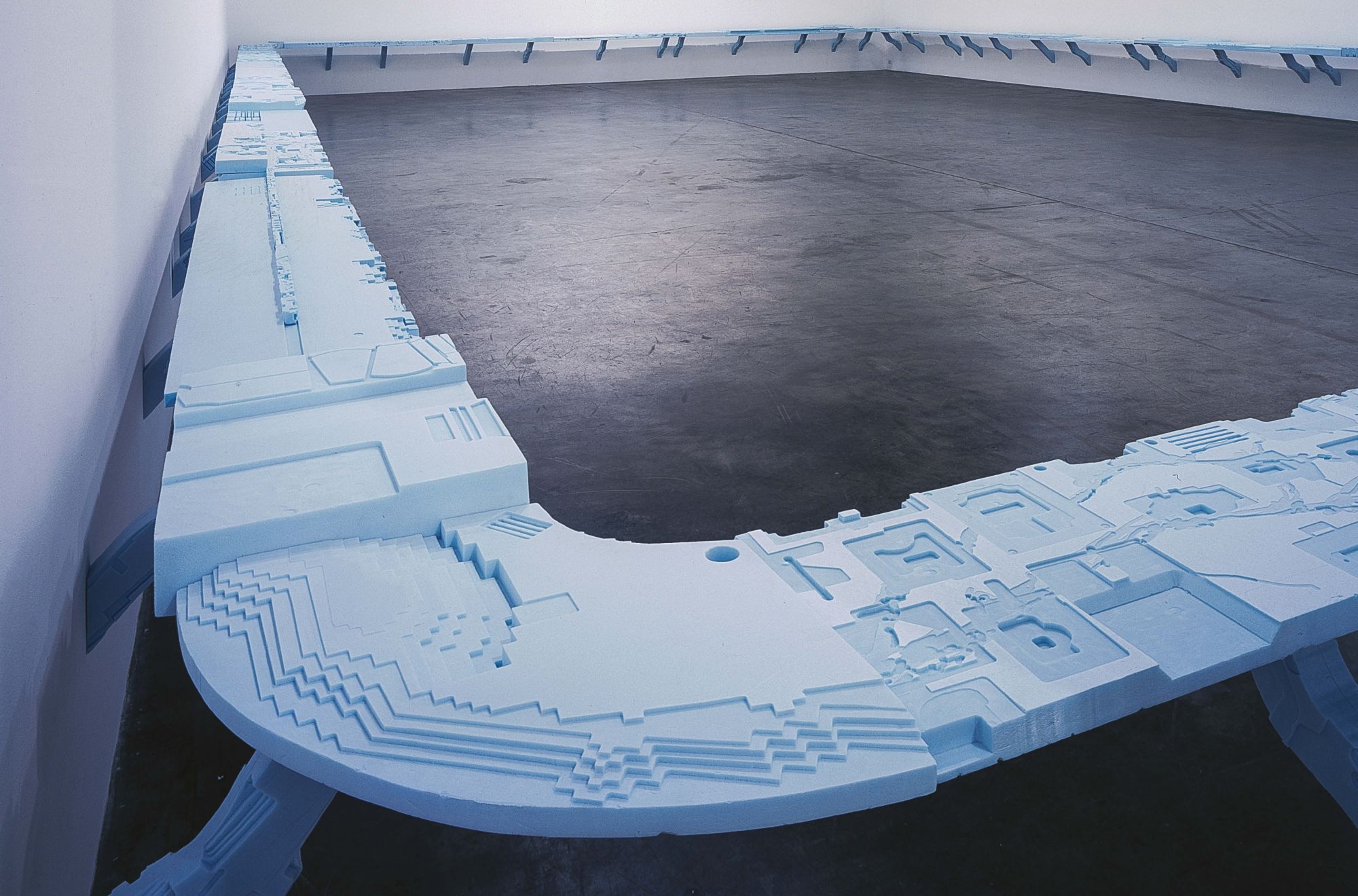

Shirley Tse, Polymathicstyrene, 2000. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist. Image: Gene Ogami

Over the past thirty years, Hong Kong-born, California-based artist Shirley Tse has developed a multivalent installation practice exploring sculptural processes as “models of multi-dimensional thinking and negotiation.” After studying fine art at Chinese University in Hong Kong, she arrived in California in 1990 to attend University of California at Berkeley and subsequently ArtCenter, where she earned her MFA. She teaches at CalArts and represented Hong Kong at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019, with other recent international exhibitions at M+ in Hong Kong and the Wellbeing Summit for Social Change in Bilbao, Spain.

I sat down with Shirley in her Los Angeles studio to discuss two of her exhibitions in 2022—Lompoc Stories at Shoshana Wayne in Los Angeles and time going backward and forward for The Magic Hour, a shifting outdoor structure for the display of artworks in the desert of Twentynine Palms. Her current work is informed by her recent move to the Central Coast town of Lompoc, in rural Santa Barbara County, and converges natural and human-made materials to reveal the unsustainable, anthropogenic footprints left on ecosystems we imagine as pristine. Our conversation evolved into a discussion of environmental and economic sustainability, transformation and plasticity, and human and non-human cohabitation in an era marked by ecological and social crises.

Vanessa Holyoak: I’ll start with a question about sustainability. Each work in Lompoc Stories, your show at Shoshana Wayne last year, was priced at $3,360, which was the bimonthly cost of your studio rent in L.A. Your work often plays with multiple valences of a word—plastic, plasticity, polysemy…. Lompoc Stories invokes both economic and environmental sustainability in the context of anthropogenic climate change. I’m wondering how you see the parallels between these two forms of (un)sustainability that are currently playing out in our world, and how your sculptures themselves contain or reveal both meanings.

Shirley Tse: Yes, I don’t think they’re separate. First of all, the choice of material and the narrative arc in Lompoc Stories both address the non-human stakeholders. In part, it’s about practicing multi-species co-living and dying—how do you live and die well together with other species?

But I would say environmental sustainability and economic sustainability are one and the same problem. I have been thinking about sustainability for a long time, and to clarify, for me it has multiple dimensions. In the more common parlance, I think most people associate it with the climate crisis. That’s definitely one big problem of sustainability, but I think the economic aspects of it are also huge. I’m talking about economic disparity, which is totally unsustainable—it’s just insane. Another aspect of sustainability is mental health, and how the art world expects a certain pace for making and showing work to feed the neoliberal market. Roughly, this is three-pronged, but I’m sure there’s more.

And I should make a note that Shoshana Wayne is a commercial gallery, so that number—$3,360—factors in a gallery commission as well. We both know contemporary art prices are crazy. So instead of pricing the work so exorbitantly high with no explanation of why, I’m making it very clear, so there’s full transparency.

Installation view of Lompoc Stories. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist.

VH: It’s in proportion to your need to sustain your practice.

ST: Exactly. Because when you’re trying to determine how to price an artwork, you can use production costs, material, labor, and then some crazy abstract factor, the “hot” factor, whatever. But all of this is intangible. The one thing that is very tangible is that an artist needs space to keep making work. In my case, that space is my studio, so I’m shifting the focus from commodity to sustainability.

I actually had an opportunity to get a bigger studio, but I decided against it. In my past work I made large-scale installations and those were unsustainable in terms of shipping and transport. And if the work is not collected by a museum or sold by the gallery, I have to find storage. And if my studio isn’t big enough to store the work, I can’t keep it and it ends up in a landfill. And if I get a bigger studio, I might not be able to manage the rent… I decided that I needed to devise a more sustainable way of making things without sacrificing the large scale that allows for the body to interact and negotiate, because aesthetically that’s really important to me, too. So maybe the work will become collapsible, or modular…

Details of Negotiated Differences in Stakes and Holders, 2020. M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong. Collection of M+. Photo: Ringo Cheung

VH: I really enjoy, too, how the effort to be sustainable becomes part of the concept of the work itself. It’s not just an afterthought but inherent to the work.

ST: It has to be that way, though, otherwise it will become a limitation and then it will become artificial. The way I do it is integrated. That actually gives me joy. It’s like a challenge to myself. It’s very important.

When we hit COVID, we ended up doing a remote installation in Hong Kong that was very successful, even though the work is supposed to be improvised and site-responsive. It’s easy to do a remote installation if you have a fixed plan, but there’s a lot of setup needed to allow for improvisation to happen remotely, and we did it. The point is that it drew a lot of attention from the media for being a remote installation. I was bombarded by the press about the “new normal.”

They were all asking me—is this how the art world is going to do things from now on? Especially if they don’t need to spend money on flights and accommodations anymore. Some even asked me whether I would just start making art for the screen. My answer is that I don’t know what the “new normal” is, but I know the old normal is utterly unsustainable. Look at the carbon footprint associated with the Biennale and art fairs. It’s obscene. And the pace of churning out new work, transportation, creating storage—it’s unsustainable, environmentally and financially, for artists who don’t have market or institutional support. Systemic inequity and oppression within the institution is unsustainable. And all of this is against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter, as well as the protests in Hong Kong.

Exhibition view of Stakes and Holders, 2020 at M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong. Commissioned by M+. Photo: Ringo Cheung

VH: Speaking of the Biennale and Hong Kong, Negotiated Differences—the project originally produced for Hong Kong in Venice at the 2019 Venice Biennale—is this sprawling sculptural installation composed of handmade and 3D printed wooden parts, held together in a loose interconnected framework. Your recent work for The Magic Hour in Twentynine Palms, time going backward and forward, reminded me structurally of that system of conjoined parts. Are there any through lines in your thinking that may have informed both?

ST: I actually haven’t thought about it that way, so I like how you make the connection. My work for The Magic Hour, Decommissioned Inter-mission (2022), is actually a very different version of how that piece was first produced in 2004. I was making that work back then—it was called Inter-Mission—right after Bush got reelected. So I was looking at voting booth structures. A voting booth is supposed to be a private space within the public space, so it reminded me of a bathroom stall, which is also a public-private space. Then I was thinking about art fair booths too, which are kind of awkward in the same way.

But to answer your question, in that sense the booth is a kind of infrastructure that implies uniformity and equal distribution of space, and of power. The booths are all the same size. Negotiated Differences is similar in that it also considers infrastructure. But I think the big difference is that the booth structure is a parody of the institution, which is uniform, limiting, and artificial. Whereas the structure of Negotiated Differences encourages exercising agency, as opposed to uniformity.

Shirley Tse, Negotiated Differences, 2019, carved wood and 3D-printed forms in wood, metal, and plastic, dimensions variable. Hong Kong in Venice, 58th Venice Biennale (2019). Courtesy of the artist and M+ Hong Kong. Photo: Ela Bialkowska-OKNO studio

Shirley Tse, Decommissioned Inter-Mission, 2022. Image courtesy of The Magic Hour.

VH: Inter-Mission functioned as scaffolding that supported six sculptures which are now being held hostage by the Artist Pension Trust. Could you elaborate on this idea of—to borrow language from The Magic Hour’s press release—liberating the structure from its institutional or supportive context?

ST: In terms of liberation, it’s a tricky word. It comes with baggage, and lately I’m having a fundamental reexamination of what is freedom and what is liberty. But I was using that term in the press release to mostly signify agency.

[…] When I moved from L.A. to Lompoc, I thought about renting a space to store my work. But then I asked myself, for what? Just in case I have a retrospective in the future? Even with $150 monthly rent, which is really cheap, if I wait 10 years for a fantasy retrospective, I end up spending 20K. Only for the hope, if not a downright fantasy, of being included in an institutional legacy. I asked myself, what is legacy, anyway? Isn’t it better if my friend who loves the work gets to live with it in their home right now? So I gave away a lot of artwork instead. That was so liberating. It should have a life to itself.

VH: Instant Archaeology, another piece that was on view at The Magic Hour, resembles an ice core sample, but is made entirely of plastic products—polyethylene and post-consumer recycled plastics—with small hollowed-out crevices that hold other minuscule plastic forms. I’m curious about this conflation between plastics, and the reference to glacial ice, or ice core, which is a type of ice sample used to track climate change patterns. How do you think the work reconciles the causal relationship between plastic and climate change?

Shirley Tse, Instant Archaeology, 2006. Image courtesy of The Magic Hour.

ST: Instant Archaeology was made in 2007 and was inspired by watching the documentation of ice sheets, which is how scientists measure how much glacial ice we’ve lost. I wanted to make a sculpture with ice cores, so those indentations were another way to demonstrate how machines make marks on ice. But it’s not ice, it’s just foam. The plastic debris is actually post-consumer recycled resin—it’s the stuff that gets chopped up and turned into resin to be remade into other plastic products, so it looks like compost or consumer confetti.

I thought it would be funny to put this in the so-called ice core, which is actually made of foam core, a petroleum-derived product—so it is plastic. And while doing a site visit at The Magic Hour, I saw a water tank in the distance that said “BE WATER AWARE.” And then Instant Archaeology literally popped into my head as the perfect piece to re-contextualize in this desert location, because it references water, digging, the reversal of hot and cold, and the connection between carbon and water in heat transfer.

VH: Plastic and plasticity have been an ongoing theme in your work, from Polymathicstyrene (2000) to Playcourt (2020), the outdoor installation in Stakeholders in Venice. What is your investment in the potential of this material?

ST: I’ve been trying to leave plastic for many years, and it’s still with me. I don’t think we can ever leave plastic, sadly. It’s true that I’ve moved away from the material to focus more on the concept of plasticity. At one point, it dawned on me that what makes something plastic, that is, artificial, is not its material or substance. We call it plastic, nylon, polystyrene, but it’s really just carbon, a natural element. It’s an enormous chain of carbon molecules that chemists were able to coax together to form a permanent bond. So what is plastic is not the material—it’s the organization. It’s the syntax. It’s the formula that binds them together that is plastic.

VH: Could plasticity be considered the transformation of substances, or construction through the linking of a variety of substances, to create something new?

ST: I have many names for it—it’s structure, it’s construction, it’s language, it’s syntax. It’s arrangement, narrative, all of that. All of these are ways to pinpoint the underlying structure that feeds the transformation. That’s what I’m trying to add. It’s why, starting with the Quantum Shirley Series, I’m moving away from focusing on the material to focus on the structure and syntax of narrative language.

Shirley Tse, Polymathicstyrene, 2000. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist. Image: Gene Ogami

VH: The sculptures in Lompoc Stories embraced the site specificity of Lompoc, where you relocated during the pandemic. They also confront the more unseemly realities of the Central Coast countryside—especially in the video Lompoc Story, which narrates your experience of stumbling onto an off-limits military base while you were hiking. Your work at The Magic Hour, time going backward and forward was also located near the Twentynine Palms Military Base. What does your work reveal about these hypocrisies—this conflation of the military industrial complex and the illusion of pristine or “untouched” nature?

ST: This actually harkens all the way back to one of my very first projects, Vagabond or Wanderlust? in 1998 in Death Valley. I was relatively new to L.A. at that time. Coming from Hong Kong, we do not have deserts, so the desert was a mystery to me. I didn’t know what to expect but I had a romantic notion of what deserts were like. When I went out to Death Valley and discovered that there is a huge military base there, alongside all the secrecy it produces with myths about Area 51, UFOs, aliens, I realized that there is no such thing as “untouched nature” anymore, not in the United States, maybe not in the world. All our ecosystems have been completely dominated by anthropogenic use.

Lompoc Stories is a continuation of that line of work. I wanted to set up the protagonist as someone who romanticized the area as pastoral and idyllic only to encounter these discontents… Compared to L.A., Lompoc is an agricultural, rural community. Again, coming from Hong Kong, it’s my first time ever living in such a community. I’ve always lived in big cities. But it didn’t take me very long to realize that the rural is just as constructed as the urban.

VH: Many works in Lompoc Stories center “natural materials” and human-made technologies. Tar (2022) uses beach tar, antenna, and motorcycle gear. Spacesuit (2021) co-mingles found snakeskin, diatomite, and fiber optics. Crowstrike (2018) juxtaposes a helmet with charred wood. Can you talk about the coexistence, or co-dependence, of the natural and man-made, in these or other works, as well as your engagement with non-human animals?

ST: There’s always been a convergence of the body and the machine in my work; the industrial and the organic are always there. Even though I’m trying to move away from it, I can’t help it. With Lompoc Stories, I wanted to set up principles that adhere to the notion of sustainability. Firstly, I had a constraint to not use any store-bought material. Secondly, I wanted to address non-human stakeholders.

Detail image of Lompoc Stories Series: Spacesuit, 2021, found shed snake skin, fiber optics, diatomite, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

[…] The Vandenberg Space Force is a military base near me. They mostly specialize in rocket launches for the Department of Defense, NASA, as well as for Space X. I can actually see rocket launches from my house quite often. When they perform rocket launches, a plume of smoke is left behind, so that’s my way of addressing air pollution, and that trail of smoke also looks like a snake. So, when I was on that hike that I’m talking about in the video, I saw something long and shiny sticking out of the ground. I thought it was a plastic bag, so I picked it up, because I don’t like having trash on my trail. But it wasn’t a plastic bag, it was a snakeskin! A naturalist friend said the snake must have shed its skin that same day, otherwise it would have felt dry and not so plasticky. Also, it was intact, the eyes and everything were still there. I brought it home, and it was just sitting in my studio for three months until I was working on Lompoc Stories. I thought it was perfect to marry the snake with the fiber optic to talk about the rocket launch.

The motorcycle in Crowstrike also has a story. My partner Todd and I were riding on his motorcycle on the highway and suddenly this big, dark black thing hit my face. It had so much force that I had whiplash… I thought cargo fell off a truck and hit me, that’s how it felt. But it turned out that it was a big crow, or maybe a raven. It was eating roadkill and took off when it heard the motorcycle. It was traumatic because I could have been killed, but the trauma will always be associated with the big, dark unknown thing, not a crow. I wanted to make a work about it for months after. This experience helped me through the pandemic because I literally got hit by the “unknown” but I survived. Two years ago, we had a record season of forest fires. I went into the forest to look for pieces of charred wood to compose a crow shape without altering the pieces.

Crowstrike, 2018. Found wild fire-charred wood, helmet, hardware. 16 1/2 in. x 42 1/2 in. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist.

VH: The works in Lompoc Stories also lean more heavily into images than structures, which seems to mark a departure from your earlier way of working, for example in Stakeholders, and in the desert. Have you been able to track any significant shifts in your development as an artist? Do you think moving to Lompoc has formally, materially, or conceptually impacted your work?

ST: I teach at CalArts. We tried to unionize the faculty around 2016 and it was not successful. I was very upset, because it was very difficult work. […] That’s when me and my partner had a complete reexamination of our priorities and what markers of accomplishment drive us. Why should we stay in L.A. when the cost of living keeps going up and wages are stagnant? Both of us came to the conclusion that sustaining our personal creative work is what’s important. Long story short, moving to Lompoc allowed me to reduce my teaching hours and be in my studio more. And now we have the resources for clean energy. We have solar panels on our roof and I’m learning how to grow my own vegetables, actually…

Last year I was commissioned by the Wellbeing Project. It is a network of over 400 organizations including grassroots networks, foundations, progressive businesses and governments with aims to strengthen the research around inner wellbeing at the heart of social change. We’re dealing with global problems, but that effort isn’t sustainable if we’re not taking care of ourselves and our wellbeing […] They hosted the Wellbeing Summit for Social Change in Bilbao and asked me to contribute an artwork, and it gave me an opportunity to rethink my personal meditation practice, which until now I have not found a way to use in my artwork. When I meditate, one moment I have anxiety and I am laden with these neoliberal, market-driven markers of success. But when I meditate, it shows me that claiming my own agency is always available. I made a sculpture called Meditating Is Porting To A Blissful Version Of Ourselves that was installed at the Wellbeing Summit. That was actually very empowering.

Shirley Tse, Meditating is Porting to a Blissful Version of Ourselves, 2022. Bilbao, Spain. Commissioned by the Wellbeing Project. Image courtesy of the artist.

Last year I was also reading a lot about Greenland’s melting ice caps and yearned to see its glaciers before they’re gone. I had discovered The Arctic Circle residency program but realized that a roundtrip ticket from L.A. to Oslo emits the equivalent of 3.1 tons of carbon dioxide, which would melt about 9 square meters of Arctic sea ice. No artwork I can make will ever offset that. In the past I’ve placed artwork in the landscape to photograph it. But this time I didn’t want to do that. I didn’t want to take anything from the environment and I didn’t want to leave anything there. So for this residency, I basically proposed to do nothing. I proposed to just be present. Maybe I would meditate, or I might chant mantras to the ice caps and wish for them to stay cool. I laughed after I sent out the proposal, but I think it struck a chord somehow because they accepted it.

It was against this backdrop that I made Lompoc Stories at Shoshana Wayne. I was encouraged by the Wellbeing Summit and then emboldened by the Arctic Circle residency. So I gave myself the limitation that I wasn’t going to use any store-bought objects. No new shit, only material that I already have in my studio and found objects, which happened to be beach tar, a snakeskin molt, the diatomaceous earth that broke off from the hillsides…it may look like a collection of discrete objects or images—and there are no modular units that form any structure—but these images and objects together implicate a systemic precarity. My self-imposed sustainability principle drives me to scale down, pare down, and allow the work to disintegrate.

Lompoc Stories Series: Tar, 2022. Beach tar, motorcycle safety gear, antenna. 32 in. x 30 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery and the artist.

VH: In your experience, what has been the difference between working in the studio versus working outdoors? What was it like to install the work for The Magic Hour in the high desert, with all the extremes inherent to that environment? The Arctic Circle is also another extreme setting. Did these environments affect the way you work, or the work that you’re interested in producing?

ST: Oh my god, that damaged my body! I will admit, I discovered that I am not a fan of making outdoor work. It’s very difficult. Playcourt is an outdoor piece I made for the Biennale. Working on Playcourt presented many logistical challenges because it had to endure the outdoors for six months in a high traffic area. So there were concerns about the safety of the audience, the work, the elements… I went through the flooding in Venice, the protests in Hong Kong, the virus. I’ve been through the apocalypse with this work.

I really like [designer] Chris Dyson‘s concept for The Magic Hour as a shifting outdoor structure. I like the fact that it’s more accessible for viewers, because it’s outdoors and you can go at any hour. But it’s a different, physically challenging way of working. I was battling with the wind and installing in June when it’s already really hot. I know you are asking about working outdoors versus indoors, but this reminds me of another conversation about “public art.” I do like public art for how it produces energy for the community. Personally though, I like indoor exhibitions. There’s something about having to make a deliberate trip to a museum or a gallery, to visit a certain show at a certain hour. I place a lot of value on that ritual, and that you are opening yourself up to a concerted effort to meet the work halfway, ready to do your own work of experiencing. You don’t stumble upon it. That aspect, I think, is really precious.

Shirley Tse, Playcourt, 2019, dimensions variable. Hong Kong in Venice, 58th Venice Biennale (2019). Courtesy of the artist and M+ Hong Kong. Photo: Ela Bialkowska-OKNO studio