Artists at Work: Sula Bermúdez-Silverman

by Sóla Saar Agustsson

Installation view of Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl, CAAM, Los Angeles, 2020. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman is a multidisciplinary artist whose work uses assemblage, sculpture, and videography to interrogate economic, racial, religious, and gendered systems of power. Born in New York and raised in Los Angeles, she earned her BA in Studio Art from Bard College and studied at Central Saint Martin’s School of Art and Design in London. In 2018, she was awarded her MFA in Sculpture from the Yale School of Art. Her current exhibition at the California African American Museum of Art, Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl, combines found objects with dollhouses made of sugar, exploring the artist’s ancestral connection to Puerto Rican sugar plantations and the crop’s relationship to invisible economic powers. Her exhibition at Murmurs Gallery in downtown Los Angeles, Sighs and Leers and Crocodile Tears, is also currently on view. We caught up with Sula to discuss her work and what she’s been working on since the pandemic started.

Sóla Saar Agustsson: Your first solo show in L.A., Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl, opened at CAAM right as a pandemic hit and L.A. went into lockdown. Ironically, your dollhouse series is fitting for these times given that many people are trapped at home. What was it like to have a museum exhibition open during this time?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: It was open for two weeks before everything shut down. Luckily, it wasn’t the first time showing most of that work, but it was the first time showing to that audience, and also showing the dollhouse series, which was made specifically for CAAM. Those pieces are ephemeral, so it was kind of a drag. But during the process of making them I realized I was constantly working against the material. I was getting frustrated testing out ways to keep the sugar from clouding and cracking. Halfway through I decided to relinquish that control and let the material do what it was going to do. I guess that’s the way I’m also approaching the closure of the show and the slow deterioration of the dollhouses sitting in limbo in the gallery for almost a year now. I’ve gone in to check on them three or four times now and structurally they’re holding up for the most part, but there is a bit of sagging and drooping. The sugar itself has sort of mutated and the houses that are coated in resin have gone from a transparent to a translucent, so I’m sort of looking at them as tangible markers of time.

Sola Saar Agustsson: What was the protocol for keeping the works intact? Was there a specific temperature?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: No, there really is no protocol. I had no idea what was going to happen to them. I’ve just kind of been accepting the ephemeral nature.

Sola Saar Agustsson: Creating sculpture out of sugar is so delicate. Can you talk about your process making the dollhouses?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I disassembled an original dollhouse and made large silicone molds from each of the pieces. I would heat up the sugar to about 300 degrees in a pot on the stove and pour it into the molds. I used a torch to get rid of the bubbles, and then used a soldering iron to melt the pieces together and reconstruct the house. I used about 55 pounds of sugar for each house.

Physically, it’s very demanding. I would usually try to make a dollhouse in a day or two because of the quick changing nature of the sugar. I burned myself and the sugar a lot. I once had just finished a dollhouse and moved one thing and the whole house fell over and broke. It became very emotionally taxing.

Detail view of Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Neither Fish, Flesh, CAAM, Los Angeles, 2020. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Sola Saar Agustsson: I read that the dollhouses were modeled from one you had as a child. What inspired the series?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Yeah. My godmother built a dollhouse for me as a kid and I ended up dismembering it in order to make the dollhouses for the show. But what initially inspired the series was that I found census records online that indicated my great grandfather was a sugar cane field laborer. So I just started reading about sugar cultivation in Puerto Rico and the other sugar islands for my own interest, and I realized how incredibly potent this kind of simple substance actually was in the transformation of the entire society. Sugar was the plantation crop that sort of surpassed all other plantation crops in importance, so I was really interested when I read about the early uses of sugar in sculptural forms as displays of power. These huge sugar displays would be used at royal banquets in between courses, and the quantities and the preciousness of sugar was so large that it was confined to kings and nobilities, who started using those sculptures as propaganda and message-bearing objects. That was my first interest in using sugar as a material.

Sola Saar Agustsson: That’s really interesting because dollhouses were for privileged children at that time too, and sugar enabled that wealth. Even now it’s an expensive hobby for adults, and there’s a certain amount of narrative play in dollhouse building, too. Would you say that children playing with dollhouses, or even adult hobbyists, are interested in narrative making?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: What’s so interesting to me about dollhouses is that actually they were intended for adults, so they were originally off limits to children. They were called “baby houses” and were for an incredibly privileged minority because they cost as much as a regular-sized house and were used to show off wealth, just the same as these sugar sculptures. There’s also a shift in the gender-oriented organization of the dollhouses. They were first a male-oriented object, but then they became this female model of domesticity and a pedagogical tool for little girls to learn how to run a household. So I don’t know if necessarily people who create dollhouses now as a hobby are thinking about narrative making, but I do think that for children playing with dolls provides emotional development and social skills.

Sola Saar Agustsson: How did you choose the objects and the ephemera that you placed on the walls of the dollhouses themselves? Are they connected in any significant way?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Each house has its own theme. Specifically, the pink house was meant to mimic pink frosted depression glass, so the objects in the house are actual depression glass. The house with the stickers is meant to imitate the way that a car window will be full of randomly placed stickers from a child, when you can see just the back of the stickers. One of the houses is titled White Zombie and is named after the 1932 movie, which is sort of the first zombie feature that introduced white Americans to the zombie myth. The zombie myth originated in Haiti as a metaphor for the African slaves who worked on sugar plantations. They basically are stuck between the physical world and the afterlife. But now the American zombie is completely devoid of that history. So, that house, White Zombie, is filled with transparencies of stills from that movie.

The connection between why I’m using sugar and dollhouses though is really my interest in their transformations and their semiosis, as well as their connection to power individually. It sort of focuses on social structures and how symbols arise and grow and change and then die, and are culturally specific as well as arbitrary.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman, Table for Eleggua, Table for Elijah. Installation view from Neither Fish, Flesh, CAAM, Los Angeles, 2020. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Sola Saar Agustsson: Your piece Table for Eleggua, Table for Elijah combines objects that reflect your mixed heritage, like Drakels — I really like that pun by the way — hair picks, American toys like Polly Pocket, and references to Afro-Carribean deities. What importance do these objects hold to you and how did you choose to combine them?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I’m interested in syncretism and the things that emerge from it. When we look at our history we can see that many cultures and groups of people intersect and intertwine, so each of the objects occupy a position of ambivalence — the human hair becomes yarn and the picks look like forks. I’m interested in the way that the subject positions can easily be changed, and also in showing that boundaries are unstable and categories can fail.

Sola Saar Agustsson: A lot of your work deals with collecting objects. With the quilt piece Los Angeles, CA (2020), there’s detritus, like discarded toys and what I interpreted as excesses of capitalism — these kinds of fast items that get thrown away almost immediately. I wondered if you were trying to make some sort of statement about the environment.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I don’t really seek to make statements in my work. I don’t aim to provide answers or claim any kind of knowledge. I’m more interested in challenging our inherited ideas and also making known unequal and unseen sources of power.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman, Los Angeles, CA, 2018. Installation view from Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl, CAAM, Los Angeles, 2020. Photo: Elon Schoenholz.

Sola Saar Agustsson: When did you start to start working with hair?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Around 2012 or 2013. As a kid, whenever I would get my hair done, they always would remark about how much hair I had. And it’s true, like a huge furry animal would come out of my hair every time I took a shower! So I had this impulse to start collecting the material because I was constantly throwing it away. I started doing that 2012 and I still do it to this day.

Sola Saar Agustsson: Yeah, hair is something so personal and that can convey a person’s identity and background. It’s also something we shed. What did you hope to convey by incorporating the hair into the embroidery and spindles?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I guess I’m really interested in this idea of the third space, which originates from post-colonial theory and that Homi K. Bhabha speaks of — a valid space beyond the normative binary. I think it’s a place that I often occupy. I think that many of us do. So, when I spin my own hair into yarn, it becomes another material in the work and the form kind of serves as the space that’s in between. It sits on a swift and the swift is a tool that’s used to wind yarn into a skein, so the yarn is not yet being used to make something, but it’s also gone beyond the initial fiber of hair.

Sola Saar Agustsson: It reminds me of the ephemeral quality that you’re talking about and the dollhouses, too.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman, Repository II: Dead Ringer; cast glass, Himalayan sea salt, water, Florida water, 45” l x 20” w x 44” h. Installation view from Sighs and Leers and Crocodile Tears, Murmurs, Los Angeles, 2021.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Yeah, I like working with materials that are difficult to contain and that are resistant to capitalism in a lot of ways. They’re unable to be collected or preserved.

Sola Saar Agustsson: Right, or they’re not given a commodifiable value. I also think it’s interesting that you chose Rachel Dolezal to appear in your video, Duck Test, which is also installed in the exhibition at CAAM. She’s somebody who manipulated her hair to appear black or mixed when Black women are marginalized for wearing their hair natural and lighter skin or white-passing people are questioned about their heritage. What was it like to meet someone so controversial?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I think the video was more of a thinking gesture in researching her role as a figure that’s symbolic of America’s fraught history of racial and ethnic taxonomies. But meeting her was incredibly natural. Honestly, she was very easy to get along with and I never felt uncomfortable by her.

Sola Saar Agustsson: I’m curious — what did you talk about with her?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: We mostly spoke about her and her life after the controversy broke. We probably spent 12 hours straight together. And I mean, I pretty much asked her all the questions that she’s already answered in interviews. But I guess I think of it more as a personal project because her presence contends with larger societal debates about so much cultural appropriation, performed identity, authenticity, and essentialism — similar to the objects which are displayed in Table for Eleggua, Table for Elijah — and I think using her as a material revealed how simple it is for these racial lines to be crossed and the instability of these borders that we’ve set up.

Sola Saar Agustsson: A lot of your work deals with craft — embroidery, dollhouse building, quiltmaking, and even hair styling. Do you do any craft work outside of your artistic practice and do you draw a distinction between the two?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I’m starting to make clothing, which I guess you could call a craft. But you know, it’s something I think about a lot. I haven’t really figured it out yet. It’s a discussion I’d really like to have and I still don’t know how I feel about that distinction between art and craft. I need to do some more research.

Sola Saar Agustsson: I think they overlap and you can do either without having to define them. What kind of clothing are you making?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I just learned how to use a knitting machine, so I’m making knitwear right now — mostly just swatches and stuff for now.

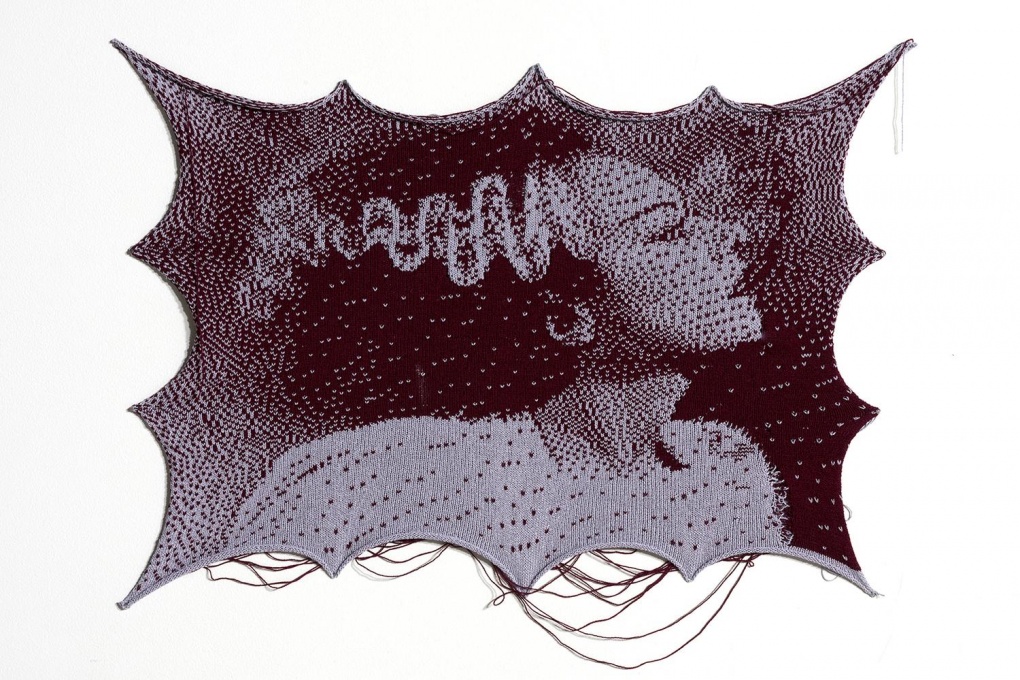

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman, The Monster’s Bride (She’s Alive!); wool and viscose yarn, 25″ l x 18″ w. Installation view from Sighs and Leers and Crocodile Tears, Murmurs, Los Angeles, 2021.

Sola Saar Agustsson: Has your art practice changed at all since the pandemic? What’s your day-to-day like now?

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: I’ve been able to work on my own practice actually much more. I lost my job at the beginning of the lockdown and I was tremendously lucky to receive grants to sustain my practice. So I’ve been able to be at my studio pretty much every day and I’ve been preparing for my next show at Murmurs, a gallery in downtown L.A.

Right now I’m really interested in monsters and horror. I’m kind of going off that one dollhouse that I talked about earlier, White Zombie. I’ve gotten really into zombies and horror, and especially the genre’s relationship to capitalism, which is automatically in relationship to race. But I’ve also been thinking about this very thin line between victims and perpetrators. I’ve been thinking about monsters as both “us” and “them,” and as poles of a split society, or a split self, if that makes sense.

Sola Saar Agustsson: I think a lot of monster myths, like zombies or vampires, derive from anti-Semitic tropes.

Sula Bermúdez-Silverman: Definitely. But I’m also thinking about the real monsters in the world, like the bloodsucking people who run our country. And a lot of the horror tropes have to do with viruses. A lot of zombies emerge from some kind of virus and then it becomes a zombie pandemic. So I’m definitely thinking about the structures that have failed during this time, and about the ways that the pandemic has exposed certain monsters, and certain invisible and unseen parts of our laboring society.