Artists at Work: Tarrah Krajnak

by Kavior Moon

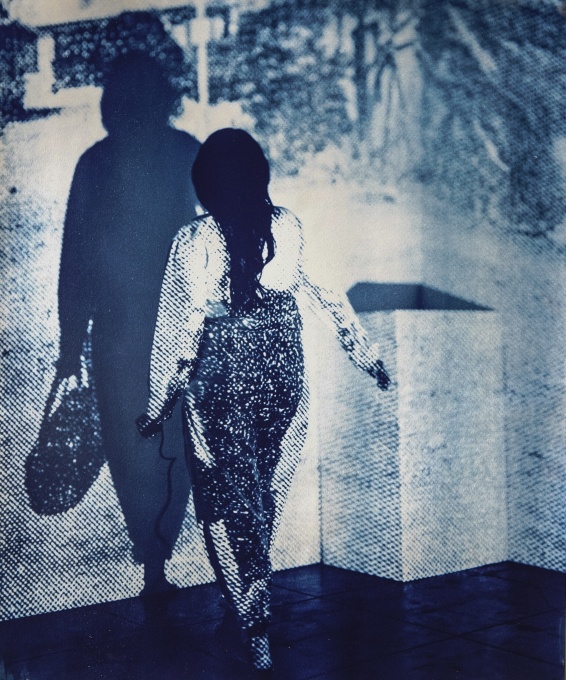

Self Portrait as Building with Child Prostitute, 1979 Lima, Peru/2019 Los Angeles, CA. Cyanotype 8×10/20×24, 2019.

Since 2013, Tarrah Krajnak has been producing photographic works that spiral around the particular circumstances of her birth. Born in Lima, Peru, in 1979, she was left at an orphanage and adopted as an infant by parents who come from the coal mining town of Lansford, Pennsylvania. The late 1970s in Peru were marked by social and political turmoil, as the country transitioned from a repressive military dictatorship to widespread bloodshed with the beginning of the Communist Party of Peru’s (also known as Sendero Luminoso, or the “Shining Path”) guerrilla war in 1980. In June 2019, Kavior Moon spoke with Krajnak about her recent works, which employ found photographs, the artist’s body, and analog photography to speak about a range of issues, from the use of archives to invent histories to the problematics of representing violence and trauma. The conversation took place in Krajnak’s studio in Claremont, where she is currently an Associate Professor of Art at Pitzer College.

Kavior Moon: Let’s jump right in and start with process. How did 1979: Contact Negatives come about?

Tarrah Krajnak: 1979: Contact Negatives grew out of work that I’ve been doing for over a decade. It started with the collection of magazines and photographs from my birth year in Lima, Peru. At first, I was just interested in the political context of Peru circa 1979, the year that I was born, and thinking about my own relationship to that year. I was trying to find a physical connection to that place because I was born there, but adopted and taken to the U.S. as a newborn. So, I was thinking about how to find out more about that particular year and wondering why there were so many orphans in Peru at that time. The main question that drove this whole body of work was, why was 1979 a year of orphans?

I was also so fascinated by these magazines that I found in Lima. As an artist/photographer, I am really interested in material history.

KM: Wait, can we back up a little bit.

TK: Yes.

KM: When did you go to Peru? And how did you find these magazines or come across them?

TK: I first went to Peru in 2011, and then I went back in 2013 because I got a small grant from the Arizona Arts Commission. One of the first things I did was to hire an assistant, who helped me find a studio in Barranco [district in Lima]. It was so empty and dreary in that space during the middle of winter.

KM: This is the studio that appears in your Sismos series?

TK: Sismos, yes. Right, did you see a picture of it?

KM: I saw some views of it in those photographs.

TK: The building itself has so much history because that part of Lima changed so much, especially during the 70s, when slums started to develop around the city. So, there were signs of an older Lima in that space. But at that time I didn’t understand this context yet, and I had no idea what I was going to do. I had this grant and now this space, but I wanted to learn more about this history. So I started to gather materials. I needed to fill this dreary space with materials to work with. My assistant, Corolla, was a young art student from Barranco and she took me to the markets downtown. At first I started collecting photographs of anonymous women that looked like they could be from 1979, around that era. Then I also started collecting other photographs that I found interesting, vernacular photographs, and then I…

KM: Were the photographs always portraits of people?

TK: Yes. Because that’s what was mainly there—there were mainly just portraits of people. Like people on vacation or the pictures of the girls that I found.

KM: Such as some of the ones over here.

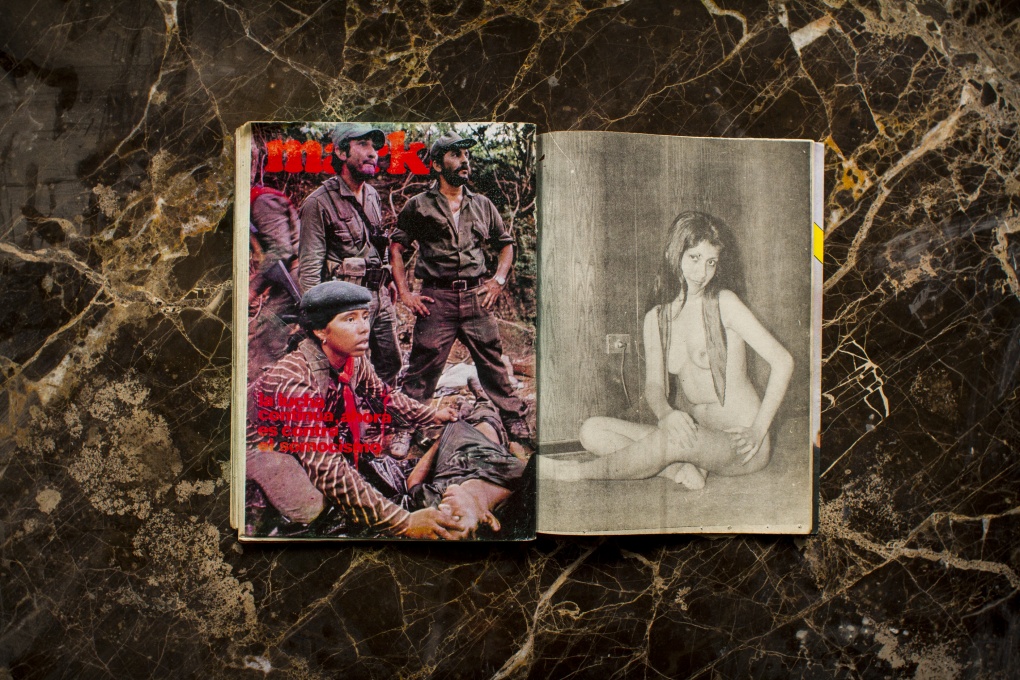

Zeta Studies, Single Line, 2014. 26 Zeta Magazines from Lima, Peru, 1979.

TK: Alex [Keefe] was with me and he would always find the best ones. He found that one. Oh, the awkwardness of adolescence here… and twinning, like I just found those two together. I started to bring all of these back to Barranco, to the studio.

In the markets you could also find these old vintage magazines. At first, I just collected some magazines, and then I was on a mission. I wanted to find every magazine I could from 1979. It took, you know, I think I was there for four months that time. It was, day after day, going into these basements, these dirty basements. Alex was with me, and my assistant Corolla was with me. And we would spend something like eight hours just looking through these boxes and piles, sitting on basement floors, sifting through these political magazines and pornographic magazines and trying to collect as many as we could.

Sometimes we would go in and notice that someone had been there right before me, to collect that same year. If you look through magazines from around that time, you see the print culture of Lima dramatically shifts after 1979. In 1979, you have appropriated pornography from the US, but also locally made pornography—I mean, there’s like this and that.

KM: It’s a bit unclear who the audiences are supposed to be, no? Male or female or…

TK: Exactly. I started looking more closely at the various bodies represented in the magazines. Other kinds of bodies begin to emerge at that time—Asian, Afro-Peruvian, Andean, gender non-conforming, and other types of bodies. I was interested in that because it says something about this moment in Peru. The moment I was born out of was shifting, moving, unclear. I was also thinking a lot about photography’s connection to the mother figure and my own displacement from Peru. How can you construct an album from archives of the anonymous, you know? How can you reclaim these bodies and make a family album out of them? How could I relate to them because they’re discarded materials, trash. I mean, they were all found in these…

Military/Nude w Hair Knife 2014, Pigment Print, 24×36 (Edition of 5, 2 A/P)

KM: They were discarded?

TK: Yes. They were all discarded. They were all found at the markets, often not displayed out with the other “valuables,” but at the bottom of moldy boxes, or underneath tables often in the back, in basements, crushed and crumpled. There was something inherently exciting about “unearthing” them, or digging them up.

KM: With the magazines, the experience is not just about looking at the images themselves, but it’s also thinking about how they’re edited and how they are presupposing a certain kind of audience. And so, you get put into that kind of—into a particular position.

TK: Right. There is an underlying fear that runs throughout the magazines too—you see it explicitly in the articles and features in the magazines depicting impotency or penile dysfunction. And there were men, I assume, who had underlined and written notes on these articles. The juxtaposition of the flaccid penis, this hyper-violent imagery, and confused sexuality I found really disturbing. Who is the sexual—who are the sexual images aimed at? Like you said, it’s hard to tell who the audience is supposed to be.

KM: You used these photographs in the magazines to create an installation in your studio in Lima? Was that…

Grau 2014, Pigment Print, 24×36 (Edition of 5, 2 A/P)

TK: Our summer is Lima’s winter. I was there in June, and it was gray. The garúa is a fog that settles over the city like a brown cloud trapping in all of the pollution and diffusing the light so much that it was dark in my studio.

I was trying to work with these magazines in the afternoon, when this one beam of light would come through the studio window. And I would quickly build a house of cards out of the magazines on the ground in that beam of light. And then I found these shards of mirror and I got these pieces of colorful Plexi sheets and started to play with them in that beam of light. And the results were beautiful. I just love the way that you could see the texture of the paper and also the way that the light changed by refracting it with the colored Plexi and mirrors. So, it’s all a very playful analog process.

KM: So, getting back then to 1979: Contact Negatives—how did you decide to make those photographs in the gallery space itself?

TK: Well, you know…

KM: It seems like a significant shift.

TK: I wanted the work to communicate something about the nature of trying to understand one’s place within this political context, how we can use archives to build histories or to invent false histories.

KM: To set up a relationship between the present and this moment in the past?

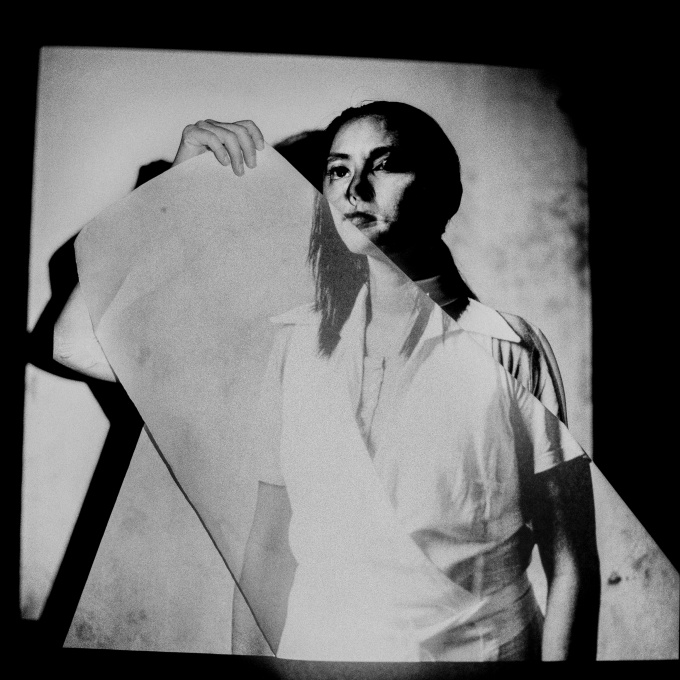

TK: So much of these earlier works was about my hand and my body, and yet they’re absent. My body is physically absent. To really understand this engagement with material, I wanted to bring my body back into the work. I did so much work before this project that had to do with the pose and the body and the ways that women in particular photographed themselves.

KM: This is the work that you did earlier, with a partner?

TK: Yes. And so…

KM: Do you have a title for that series, or were there multiple bodies of work that you did together?

Tarrah & Wilka, Hysteria Collection, Object of Investigation 1

TK: There were multiple bodies of work because we worked together for about five to seven years. There was the “Pose Archive” and the “Hysteria Collection” and “Anthology of Trends.” We were interested in photographic tropes throughout history and exposing the ways in which women’s bodies were consistently posed—for example, the “Ophelia” trope or “sick woman,” which is just as present now as it was in the 19th century. And so, 1979: Contact Negatives really merges the archival work with this performative work of bringing my body physically back into the archive.

KM: So this work is about the merging of the archival and the performative, the act of taking a photograph and making a photograph, and the archive’s relation to a person, in this case, you?

1979: Contact Negatives | Limited Edition Zine | 8”x10” | 36 pages | Staple Bind | B&W Xerox Printing, Design & Photos: Tarrah Krajnak | Edition of 75 + 15 A/P, Description: A collection of all the negatives and positives produced in the gallery over the course of the exhibition in the form of a zine.

TK: In a way these images are projected into a different time, in a different space. I’m returning to these moments, like the one where I am holding a bag titled Self-Portrait as Woman Holding Bag, or Self-Portrait as Building with Child Prostitute. How can a body return to a moment in time and space, and how does the photograph work in relation to time and space? There are many levels of re-photography here because I’ve not only re-photographed the magazine pages, but I’ve re-photographed the re-photographs. And then I’m projecting them and then I’m re-photographing that.

My initial impulse as a photographer was to go back and find these locations and just do a re-photographic project in actual time and space. I chose these particular images from the magazines because there were stories alongside the images that were about violence in some way, violence against women, or prostitution, or rape, that happened in these particular spots. But as I started to look through the magazines more, I noticed that they would use stock images for different stories. So, they would use the same photograph again for a different story. This is the nature of the archive. These photographs are just a placeholder for some narrative that is written on top of them, and then a new narrative will be written on top of that.

KM: I think we forget sometimes that when you see a photograph, like in journalism for example, you can’t always rely on the photograph to convey “truth.”

TK: Yes, exactly.

KM: There’s a kind of fissure between the media language framing the photograph and the indexical “truth” of the photograph itself. You can’t assume that…

TK: Yes. But that’s why I love photography.

KM: Because of that disjuncture?

TK: Yes.

KM: That level of abstraction.

TK: Yes. And I think earlier when we talked, you brought up Sebald?

KM: [W. G.] Sebald, yes.

TK: I think that’s why I love his books, because he’s using the photograph in a way that plays with our understanding of the real.

KM: Or maybe to put it another way, it’s that the relationship between image and meaning is suspended, right? It’s not necessarily a matter of the photograph being “true” or “false”?

TK: Right.

KM: What’s also interesting in this series is that your body itself becomes—when it enters into this scene, or this stage—a kind of representation too, right? Your body becomes a kind of cypher, a representation of someone with a particular history in terms of your link to this place and to the history of this site.

Self Portrait as Walking Woman with Bag, 1979 Lima, Peru/2019 Los Angeles, CA. Cyanotype 8×10/20×24, 2019.

TK: Yes. I mean, I thought of myself when I was making these as a cube, like that cube. I made that cube the same height and the same width as me. It became a stand-in for my body at times, so that I could look through the camera and focus. Now that I’m looking at it, and all of the photographs together, I like that aspect, the relationship between that rectangular object as my body and the way it distorts the images.

KM: Yes. It confuses one’s reading of the space in the sense that it’s a physical object with dimensionality. Its surfaces distort how you read the photographs. The image where you assume the position of the woman with the handbag seen from behind is really intense. It feels extremely vulnerable…. How do you read that image? I want to hear your thoughts and then I’ll tell you how I read that image.

TK: When I started making these photographs, I made them alone. I used mirrors, and I tried to inhabit the pose and also the person to try to… I wanted to be them or hold them or somehow touch the archive. I mean, working with a view camera and in the dark and with mirrors, there’s so much to me about photography and the occult and its connection to resurrection.

KM: That photography can do this.

TK: Yes, yes. I like the way that [Roland] Barthes writes about that in Camera Lucida. I also love early spirit photography. And the belief that you could, in fact, resurrect someone through photography.

Making these earlier versions of 1979: Contact Negatives alone in the studio was magical. They were difficult to make. It would take hours to make one photograph, and it was kind of thrilling to have that delay as well because these are all analog, right? There’s something about that process that I wanted other people to experience. I wanted that to be part of the performative aspect of this work.

KM: It’s significant, I think, that you’re inhabiting the pose of a woman, especially in relation to this incredibly violent history. To me, your body in the photograph reads as a figure who’s a potential rape victim. You know, there’s this great vulnerability to that body seen from behind. It’s totally different from the male body you see in Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog.

TK: Right.

KM: This reenactment of putting yourself into that position of extreme vulnerability—it makes me think of something that you had mentioned earlier when we were in the gallery space together. You asked, how can one work through trauma that one has no memory of?

TK: It’s true. How do you deal with that?

KM: Right.

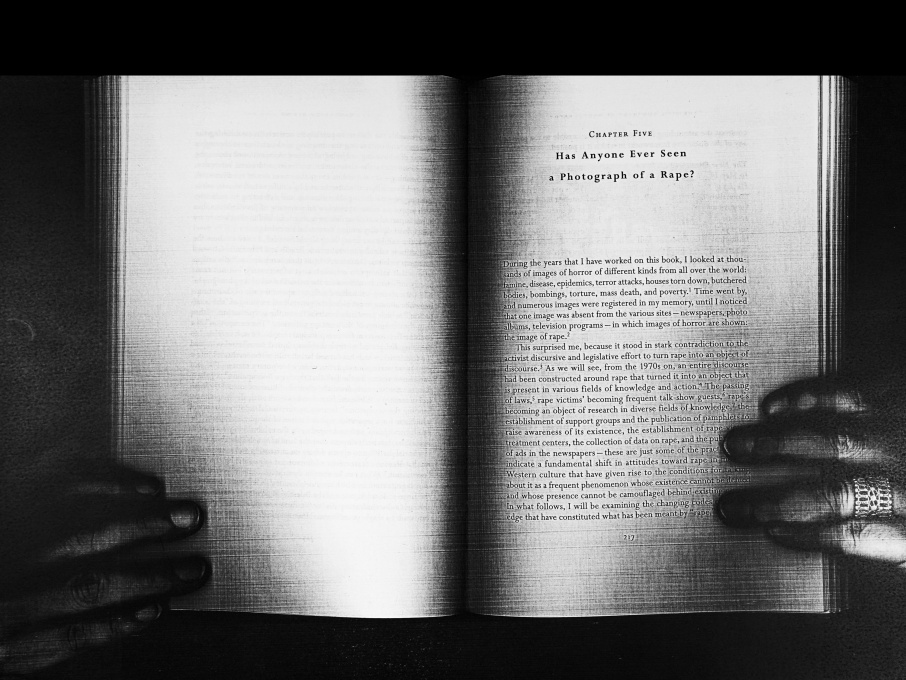

TK: Part of this work is thinking about being born out of rape. I was told I was born out of this violent act, but I don’t know if I was or not. I have no way to verify this information. So, that’s something that has really stayed with me and has prompted a lot of my engagement with the violent history of Peru. Because the story that I was told about my birth and the story that I was told about my birth mother is also a universal history. One that is also shared…

KM: Can you tell us briefly what story you were told?

TK: Yes. There are a few versions of this story. I was told that my birth mother was very young and that she came from a village in the north to work as a maid in the city, where she was raped and had to give me up for adoption. There is a lot of shame in being raped within the culture. The story sort of trails off there… and that’s it. That’s all I really have. But when I started to look into it, I discovered that this story is the same one told about a mythological folk saint, named Sarita Colonia, whose story reemerges in the late 70s and early 80s. She’s a real person, who has a grave.

Her story is the same as the one the nuns told me about my mother and my birth. Sarita Colonia was a young woman from the northern part of Peru who came to the city to work as a maid. There was an attack; she was attacked in the street. In one version, she’s raped and then she throws her body into the ocean and she dies and she becomes a saint, an unofficial saint because she wasn’t a virgin. In another version, God intervenes and turns her vagina into an elbow—and she is saved at the last second.

And so, I started to see Sarita Colonia’s image all over the city. Men in the markets would have a little image of her framed in their stalls.

KM: Oh, in the vendor stalls?

TK: Yes. And I saw tattoos of her on the arms of cab drivers… I started to see her everywhere. As I read more about that particular time period, I started to think about how stories of rape within these patriarchal cultures are very suppressed, that women have no real way of sharing their stories because of the shame. And so, logically what follows out of this suppression are myths and folk saints, and they become a proxy to speak about the trauma of rape.

I also started to read Kimberly Theidon, a medical anthropologist who did a lot of research on children born out of rape in the Andes. She went to interview the mothers. There’s this belief called the “milk of violence,” La Teta Asustada. It’s an Andean belief that if a woman is raped, her milk passes on the trauma to the child. In doing more research, I was thinking about epigenetics and the ways that this is an Andean belief, a spiritual belief, but there’s also all of these…

KM: These biological reasons?

TK: These biological reasons…

KM: For how the effects of trauma can get passed on, that they can be intergenerational.

TK: Yes, yes, exactly. And so, I was really thinking about what is my relationship to this very difficult history? And how do I think about that relationship to my own body? If it’s true, if it’s not true—to me, it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not. I’m more interested in the kinds of questions raised about one’s own identity formation, all of these complicated questions about how we emerge out of a history that is not directly ours. How are we made up of histories that we can’t even remember? What does that mean?

KM: Until something surfaces in the future…

TK: Yes.

KM: Which means one has to wait…

TK: Yes. I think there’s just more visibility now around the trauma of rape with the “Me Too” culture. There’s more visibility and more…

Has Anyone Ever Seen a Photograph of Rape?, 2018. 11×17 Xerox Print

KM: Acknowledgement of violence against women?

TK: There are more ways that women are speaking about their experiences now out loud. I mean, it is difficult work to make because I am dealing with this violent history that is mine but is not.

KM: Yes. In our last conversation, I asked about emotion in relation to your work. I think that the emotion I get from this series is actually one of dissociation, which is very much linked to trauma. It’s one way to respond to trauma, where you disassociate from your body and from your experiences, as if what’s happening is not happening to you.

And there’s a way in which… there’s a sense of repression. The images are just hard to read. There’s a kind of opacity as well as disconnection that seem to be operating.

TK: As I was just listening to you say that, I’m seeing this photograph. There’s a split here, as if the shadow is me. I am the shadow, but I’m also looking at myself. I’m looking at myself looking at myself, actually, because I’m also the one taking the photograph. I mean, there’s a lot of that—how does one look at oneself? A large part of the research that I’ve done has to do with orphanhood and the orphan figure in literature. I’ve been thinking about the ways that orphaning works and orphanhood in relationship to modernity. And I think that also has to do with the impossibility of return.

The orphan figure is one that is cut off. The more I think about adoption and orphaning, it’s really a process of projection—of overlaying a different identity on top of a body that is supposed to be “without history,” a “blank slate.”

KM: What does “to orphan” mean to you, or “orphaning”? How do you understand that?

TK: I relate it to exile from one’s own body.

KM: Always being “at sea,” in a sense?

TK: Well, I want to say that the dissociation you’re talking about is like displacement. A displacement and exile from one’s own body, from one’s mother. Whether that mother figure is a familial one or a place or an imagined history, it’s a kind of cutting off from.

KM: When you went back to Peru, did you feel any sense of familiarity or…

TK: I grew up in the Midwest surrounded by a lot of white people, very Eastern European. When I was in Peru, I looked like I belonged there, and people spoke to me in Spanish. People were very confused when they heard my Midwestern accent and first-grade vocabulary. And I was there with a white partner. There was a lot of misunderstanding initially because I didn’t understand how my body “read” in Lima. Some of the derogatory terms that I was called, like brinchera, can mean “social climber,” a local woman of lower class who only dates foreign white men and often traps them by getting them pregnant.

KM: So class was involved, too.

TK: Yes, exactly. The experience of returning to Peru created a hyper awareness in me of how race and class are so interwoven and written onto bodies externally through these cultural socio-historical factors that I had very little or no access to because I grew up in the U.S. with Eastern European parents. My parents and grandparents come from a small coal mining community where there is an entirely different—and just as complex—system of external forces that define the relationships between class, race, privilege, and exclusion. Much of this is tied to the exploitative history of the coal mining industry itself. I grew up with this history, so I understand it, but I am not a part of it. I was a complete outsider. My brother, sister, and I were aliens. We had no identity there except as the “adopted ones,” or the “brown ones.” This is the experience of the transracial adoptee, in that you are never aligned properly. Everything is skewed. I have always been drawn to photography as a way to pose questions about race and class because the medium itself has long been used as a tool to police, racialize, catalogue, and control bodies like mine—bodies of color, immigrants, outsiders, anyone deviating from the white normative ideal.

1979 Contact Negatives Installation, 1979 Lima, Peru/2019 Los Angeles, CA

KM: Looping back to 1979: Contact Negatives, can we talk about your white jumpsuit? Because it’s white, you can project more easily onto it, so that the images can be read more clearly. But do you also see it as a kind of uniform, signifying “artist at work”?

TK: Yes. The white jumpsuit serves two functions. I think it becomes a metaphor for some of the things we just talked about—the body of the transracial adoptee as a surface on which other identities can be projected. I also think of the jumpsuit as having a utilitarian function, more so than the tight bodysuit I used to wear in past projects. The jumpsuit is meant to signify “work,” and I wanted the “work”of the photographer/artist to be part of the way an audience would understand what was on display in the gallery, that is, the making of the photograph itself as a performance.

KM: Can you explain the temporal structure of this work/exhibition? Did you take photographs and then display them? What did you do during the show’s opening?

TK: I set everything up the day before the opening to test my work-flow. The “performative” aspect of the exhibition was to make the photographs there from start to finish. I wanted to be sure that I could actually do everything in the gallery. I was shooting 8×10 film, so it was a more complex process. I have to load the film into film holders inside a black bag, light meter the situation, focus the camera under a dark cloth, load the film into the camera, move it into place, take a portrait of myself with a cable release, unload the film in a dark bag, load it into developing tanks, develop the film, dry the film, then print it using the cyanotype method, which involves pre-coating paper and then exposing, washing, developing, and hanging it to dry. It’s quite a lot of “work,” so I tested it out the day before so I could have some negatives already drying. I then shot five more exposures and made five more prints during the opening. I continued to go back to the gallery and made more work throughout the month of the exhibition. I thought it was important to reveal the work’s process because the history of photography is so important to my practice and so is working with analog materials. Analog materials for me heighten photography’s capacity for chance, slowness, and a more meditative experience.

Time Twin (Part of Triptych), Self-Portrait as Angie, Lima, Peru 1979/Lima, Peru 2014/Claremont, CA, 2018. Pigment Prints or Silver Gelatin Prints, 24”x24” each

KM: Some of the images you used in 1979: Contact Negatives also appear in some form in your book The Garden of Forking Paths [El Jardín de Senderos Que Se Bifurcan], named after the Borges short story. In this book, you also insert your body into projected images of re-photographed magazine photos and play with notions of doubling, splitting, the uncanny… a sense of multiplicity that becomes unruly and unsettling, one that seems to collapse past into present and vice versa.

TK: The Senderos book was my attempt to try to bring this Peru work to completion or somehow “contain it.” I thought the book form itself might push me to do so. Most photographic monographs are made when a body of work is completed. Once a photographer has published a monograph on his or her work, he or she can move on to a new body of work. However, once I started making the book in physical form, cutting out photographs, making them various sizes, pushing them around on a table, and pasting them next to each other to create new juxtapositions, I realized that this work cannot be so easily contained. From this physical handling of materials a new visual language emerged for me. The work grew outwards, and the book served not so much as a container, but rather as a path towards the 1979: Contact Negatives work where my body became more present.

KM: This Borgesian notion of “the garden of forking paths” seems to play out as a metastructure for all of your “Lima, Peru” works. Each presentation of work takes on a particular format, whether it’s a book or an exhibition structure, but the project itself just keeps on going, in that the number of possible configurations and reconfigurations is potentially endless.

TK: I know. The project has no end and no beginning really…. New questions emerge from each iteration of the project. Poetry has been a good way for me to think through issues such as displacement, class, race, and historical trauma. It feeds back into the visual aspects of my work in unexpected ways. My body is more present in this new work, but that happened gradually as I started to research and write more about my relationship to these disparate histories, my adopted family’s history as well as Lima’s history. This exhibition 1979: Contact Negatives is really just one iteration of a larger, ongoing investigation.