Artists at Work: Todd Gray

by Silvi Naçi

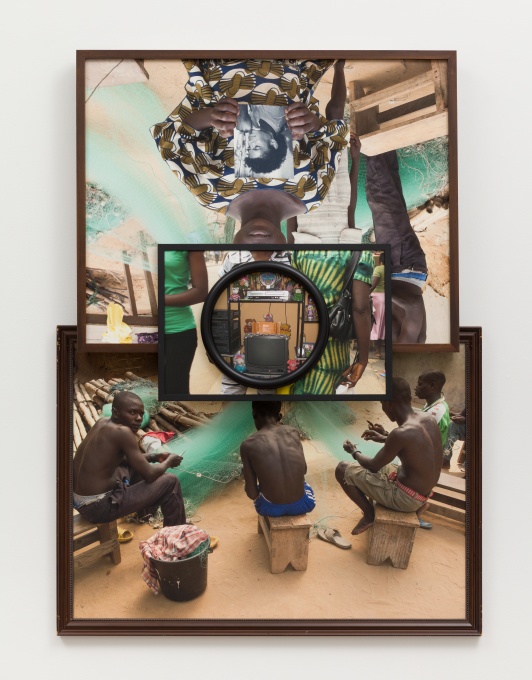

Flora Africanus (D.C.) 2018, Two archival pigment prints in found frames and artist’s frames and UV laminate // 31 1/4 x 40 x 2 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

I first met Todd Gray in 2015 when I served as the assistant curator at Samsøñ in Boston, MA, and presented his solo exhibition: Caliban in the Mirror 2.0: Exquisite Terribleness. Gray’s studio practice extends across continents and is fueled by cultural hybridity, body politics, and the use of pop culture to comment on the world at large. Working with his extensive archive—photographs of Michael Jackson, scenes of Western and Southern Africa, and his personal life—Gray produces temporal and sculptural photographic works that juxtapose decontextualized images and offer reconstructed histories to confound issues of singularity.

The artist’s work has been featured in several recent solo exhibitions and in 2018 he was named a John S. Guggenheim Fellow. From his time working with Michael Jackson in the 1980s to his show Portraits at Meliksetian | Briggs in Los Angeles (2018), the conversation that follows highlights the imperative to use sociopolitical frustrations to push our work.

Silvi Naçi: How do you think about ways in which the viewer can construct new futures through your work? I am recalling Frantz Fanon, who said, “Decolonization, which sets out to change the order of the world, is, obviously, a program of complete disorder.”[1] How do we reconstruct and rebuild histories?

Todd Gray: New futures, new imaginaries, new propositions. I want the viewer to be very active, so that normativity is contested, and I think that’s why the pieces have this, what I call, “polymorphic” aspect to them. They change the relationships of what I’m uncovering, what’s revealed—where the viewer is standing allows them to make multiple narratives, and that’s what I’m really after. Hopefully, while they’re excavating meaning and forming these narratives, affect can occur. I can’t control what that affect is but I want some sort to come about. Hence using no glass, or used frames, or framed photos screwed on top of other framed photos, as well as representing Black bodies—I’m challenging all of these normal rote art or photo solutions.

That actually comes from Stuart Hall, or as I understood Stuart Hall. It was Carrie Mae Weems who introduced me to his essays, she just got on my case and beat me up because I wasn’t reading him.

SN: Hall writes, “Identity . . . [is] formed and transformed continuously in relation to the ways in which we are representing and addressing the culture systems which surround us.”[2] Is there any relationship to that in your work, in particular thinking of the current political situation and in the way that we think about ourselves?

TG: I’m always thinking about—and anticipating—how the viewer will respond to the body and these issues of representation. A viewer projects onto a canvas or a photograph—they’re not reading, they’re projecting. That’s why there are hardly ever faces, because I don’t want the viewer to automatically project what they’re used to seeing. They have to rethink what they’re looking at, start from scratch, and actually participate in the building of meaning—it’s not predigested for them.

I choose frames that have history behind them because I want to bring that in. I want to bring in the history of this family where the frames used to hang on the wall—look at these marks and scars. There’s been a lot of handling of these frames: the frame has a narrative, the picture has a narrative, and the relationships between all of the components have their narratives.

SN: How do you select your frames? Can you talk about the process of stacking them and overlaying the photographs upon each other?

TG: I visit secondhand shops and garage sales around my neighborhood, South Los Angeles—predominantly, Black and Brown families live here. Frames that hold a variety of class signifiers and represent different levels of so-called taste or aesthetics attract me. When I stack the frames and obscure views, I’m thinking about the physical, sculptural object of a framed photograph, how to emphasize those qualities and collage images, covering, layering so more questions are raised than answers provided. Photographs as documents are assumed to make declarative statements—I want the works to present questions instead.

SN: I love that you have Earth and the cosmos represented in some of the works. The subjects live within these two spaces: the tangible and the void, reaching for the stars. It feels like I enter in and out of each piece, a vacuum effect in the construction that brings me back and forth from where you might want me to look. There’s a micro and macro effect in each one.

Can you talk about the different sites where the photographs are created, and the relevance of location in the work?

Akwidaa: Phase Patterns, Unit Structures, 2018, Four archival pigments prints in artist’s frames and found frames with UV laminate // 52 1/2 x 38 1/2 x 5 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

TG: This [Akwidaa: Phase Patterns, Unit Structures, 2018] is the fishing village that’s near our house in Ghana, called Akwidaa. As you can tell this is the same scene. So, there’s these fishermen making their nets. Then this [pointing at the rectangular center frame] is in Accra, the capital city. And this [pointing at a round frame on top] is Cape Coast, where the slave castle is. It’s really three aspects of Ghana: the fishing village, rural/cosmopolitan Accra, and—although this image shows all of this “modern technology”—a place a few blocks away from where the slave castle is. It’s an amazing embrace of, you know, Western consumerist ideology. These two men were my drum teachers. I took some lessons in Cape Coast and then asked to take their portraits. They agreed and then I saw this in their living room—it’s all their prized possessions.

SN: How did you decide which works to include in your show Portraits? Can you describe the relationships you’re creating between natural elements and their synergies?

TN: It’s about the flow. I had more, of course, but I selected work that flowed together. I was really looking at wilderness landscapes and how images of nature work with portraits. This is an early Michael Jackson shot and the two photographs on top are both from South Africa (Double Positive, 2018).

I did a residency in South Africa in 2017 at NIROX—it’s located on a UNESCO world heritage site. You must go to this place because the earliest fossils of hominids were found there. I felt like, “Oh my god, I’m at the birthplace of humanity.” So, these trees became really significant, especially in Flora Africanus (2018), because that’s where we come from and this is a tree at this place from where Africans migrated—they went north from there and I just thought “I have to take this shot.” Then I was getting frames from Johannesburg, Soweto, and South L.A.

The photograph of Michael in Double Positive I took in ’79 at a party after the Jacksons gave a concert in Los Angeles, and the tree photographs were made while I was at the residency. I like the temporal shifts embedded in the piece.

Double, 2018, Three archival pigment prints in found frames and artist’s frames and UV laminate // 31 x 43 x 2 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

SN: How do you think about constructing—or how do you know when you have found—that relationship between narratives you’re after?

TG: I recognize it. That’s something that I cannot communicate linguistically. I can only say there’s cognition through observation.

During my residency [at NIROX] I became more aware about South Africa. South Asians living there are classified as “coloured” and they are also victims of apartheid but a little less so than Black Africans. I concentrated on three of the fellows who I had photographed at the Rockefeller residency [Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Residency, Lake Como, Italy] and made work using South African foliage to talk about colonialism. That’s the first departure from Michael Jackson—these three works right here (pointing) I made with the other fellows. There’s no reference to MJ at all, but it’s still my visual language.

SN: Did it feel different for you to make this new work?

TG: Well, look how I’ve interspersed the new work with [looking at Flora Africanus (D.C.), 2018]—that’s an audience at a Jacksons show and a tree root from South Africa. They feel, I don’t want to say integrated, but they flow well together.

SN: In Purnima (2018), I love the textures in the clothing, the tapestry, the floor, and the foliation. Tell me about these works you created with your other fellows in Italy.

TG: This tapestry is an Occidental view of the Orient—imagine this nineteenth, eighteenth, or seventeenth century idea.

In the [Rockefeller] residency, they mixed scientists, artists, and people in public service together. These people were just massively important. Purnima [Mane] here used to be director of the Women’s Global Health Initiative at the United Nations; Samita [Sinha] is a musician, and then Manil [Suri], who has a PhD in mathematics, is also a part-time bestselling author. He wrote the book The Death of Vishnu, which is really good.

And in this other piece [Slipping into Darkness, All the Honey Gone, 2018], it’s the first time I’ve done a work with no human subject at all.

Purnima, 2018, Three archival pigment prints in found frames and artist’s frames and UV laminate // 55 x 48 x 3.5 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

SN: How do you know when you want to work with a particular subject?

TG: I knew I wanted to make a statement about the Indian Diaspora because I saw how colonized subjects were treated in South Africa, plus I wanted to expand my language outside of just Black bodies. I want to show parallels. Because I had taken a portrait of all the fellows—about twelve in the residency—I went to my files and took one of them plus the images of the olive groves in Bellagio and I made works.

SN: There was another version of Maya Venus (2018) titled Systems (after Fanon) that you showed at Samson, wherein we first see the lake photograph sideways and the figure sitting underneath that frame with its face blocked out by an obscure, blurry silhouette in a circular frame.

TG: Yes, it had a close-up shot of Snow White—I called it Snow Black—but it was just a very abstract view. When I originally made the piece, I had three versions and couldn’t decide what was going to be up in the gallery. Then after a while I realized this is strong, so I executed it this year.

SN: Who is shaking hands here?

TG: Chuck Berry and Michael Jackson.

SN: Why don’t you include glass in the frames? I’m asking in relationship to the Black figures in your work and what it means not to have them protected by glass—thinking of the separation between the viewer and the subjects: Can you speak to this vulnerability?

TG: No reflection. You only get the image, not the reflection of your own image in the glass.

I was at a Roy DeCarava exhibition like twenty years ago and, as you know, his work is really dark and behind glass. It’s like a mirror. He had to use special reflective glass, and I thought the glass got in the way. That was one negative experience.

Then, reading Stuart Hall, he said you’ve got to question everything. Anything that’s normal—challenge normativity, normal behavior, normal habits at every point you encounter them and rethink them. Or at least that’s how I understood him.

SN: When looking at your work I’m reminded of films by the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène, who always opposed the colonial hegemony, politics, religion, and dominant discourses in Africa and gave a voice to the underrepresented. His film Black Girl follows the fate of a young woman, Diouana, who moves from Senegal to France during a time when African immigrants were able to work with white French families but ended up treated as slaves—a supposed post-colonial moment that was worse than her situation at home. Diouana ends up killing herself in the tub, which reminds me of David’s painting The Death of Marat.

Are there any such oppositions that you address?

TG: I work against preconceived notions of representation, and I want to offer new representational narratives, or new narratives of representation, because the other ones are restricting, confining—I offer something that’s expansive. For myself, I’m conflicted about showing Africans in a rural setting and not enough of the cosmopolitan aspect, because of the stereotypical idea that Africans are in the bush. But I do have the studio in the bush [laughs], so I’m always trying to work with that. I don’t feed into any narratives that Africans are not cosmopolitan, not urban, that we are passive. I’m constantly strategizing to oppose narratives that maintain our subjectivity as minority, as other, and offer up new one.

Maya Venus, 2018, Three archival pigment prints in found frames and artist’s frames and UV laminate // 47 1/4 x 34 3/4 x 2 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

I’ve been doing this since I was in graduate school at CalArts. Back then, I was reading a couple of slave narratives so I could really be aware of how much blood and pain I was resting on top of to be in this point, to be there. And my peers would offer support, but also push-back — Cathy Opie was there, Lyle Ashton Harris was there. Allan Sekula and other people of note were there. I studied primarily with Allan, Catherine Lord, Mary Kelly, and Douglas Huebler.

SN: It makes sense that you worked with them. There is a generosity in the work, and your way of thinking about American history is generous toward people of color and immigrants, imagining new structures and narratives while allowing viewers to safely create these dreams, because it’s from America.

TG: Such good brainwashing and propaganda we have.

SN: There always seems to be a force of juxtaposition—of time, of place, of history—that comes together in your work so beautifully.

TG: I like the shifting—the temporal shifts—that take place because a photograph freezes time. These are the same images, yet there’s a few time shifts: a time shift for the photographs and one for the frame, especially because it’s an early-twentieth-century frame, the circular one. So before any of these photographs were born, that frame existed.

I like looking at Samita (2018) because it’s very peaceful. It looks like where I want to be psychologically. I want to be like this [makes yoga position gesture], and there’s a restfulness about Manil also. He looks a little more posed, but there’s so much in our heads and I can almost hear “Om” coming out.

SN: It’s quite different if we think about the violence that cropping an image could have, but a viewer feels an opposite effect when experiencing your works. They are peaceful and all the different parts seem to belong together naturally the way you’ve presented them, even if no one else could have conceived them like this.

Samita, 2018, Three archival pigment prints with found and artist’s frames and UV laminate // 39 x 46 x 3.5 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

TG: I think of them as low relief sculpture. It’s important that when one comes around to the side of the piece, that they don’t see the body. The photo starts revealing itself as they move and their perspective shifts. There’s a dynamic that I like.

SN: Have you thought of doing freestanding work that pulls away from the wall?

TG: Part of my proposal to the Guggenheim included photos that come out maybe a foot and a half or two feet from the wall. Staggering, which means building a grid system of frames to allow the work to come way out. I’m sure at some point it will have to come off the wall entirely but right now I want to investigate what happens if I can invade and impede on the space more.

SN: And that would change the way that the viewer interacts with the piece, and also intertwine with the history of the architecture.

TG: Well, it’ll activate the architecture by putting more distance between the viewer. Ultimately I want to intrude more into the space so they have to physically move around it.

SN: Has your recent Guggenheim Fellowship affected your practice?

TG: I believe you must own what you have. You must own it—that’s what this fellowship has done for me. Being a Black person and always trying to prove I’m smart because of my position in culture, knowing how people perceive me, smiling a little more and being a little more gentle so they won’t think I’m going to be intimidating. I mean, that’s how I was raised to survive, because of the milieu that I grew up with in the ’50s and ’60s.

For the most part, people will see the negative, project the negative. I don’t mean giving a full-on smile, I just mean I have this relaxed pleasantness that’s quite practiced. Even if I’m annoyed, I just take a breath and smile—a slight air of pleasantness on the edges of my mouth to project gentleness—because if I’m not relaxed, then I’m a screen they can project anything they want on to, and nine times out of ten, it’s going to be fear. If I do that [smiles], then their read of me and the semiotics I’m transmitting change, and the screen on which they project their own ideas about me is altered.

SN: When did you feel like you had to start doing that, your whole life?

TG: That’s how I grew up, in a time where my parents told me how much adversity there was going to be, how unfair it was going to be. And you can’t be angry. Not that you can’t be angry, but you can’t show it. You don’t want to have this negative attitude. You want to be pleasant because if you have an attitude about all the inequities that you’re going to encounter, you’re not going to survive. You must acknowledge the inequities and then move forward.

I was shooting a job in Texas and I had a white assistant. The client kept on asking him, “Do you want this, or should I wear this, or should I have this?” He kept saying, “Ask the photographer. I’m just the assistant.” But this white Texan kept asking my white assistant, even though nothing’s going to happen on set without my approval.

SN: Can you talk about your decision-making when combining images shot in Africa with outer space imagery and your photographic archives, in relationship to the Black body in a global context?

TG: If you reconstruct your question, you will receive the answer [laughs]. I’m actually using all of these things to reposition the Black body in global context—but as cosmic beings, not limited to human beings. We came from stardust, and we forget that we’re more than just humans. We’re stardust. We’re cosmic creatures. I don’t mean that in the ephemeral, hippie, LSD way—I mean that as straight-up science. So, if we can think of ourselves more broadly than human subjects, maybe we’ll start thinking of the ecological consequences that we bring upon ourselves. Maybe we’ll start thinking of ourselves in a greater historical context.

Slipping into Darkness, all the Honey Gone, 2018, Three archival pigment prints in artist’s frames and found frames with UV laminate // 51 1/2 x 60 1/2 x 4 1/2 in © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

SN: Yes, you’re very eloquent in how you think and talk about your work, which I find makes me wonder how we can best do that when we are not from the dominant culture? Isn’t this eloquence a sign of privilege?

TG: Well, I’m not going to limit my power. I’m not going to limit my imagination. Because in my artmaking I can imagine without any limits. I’m also not going to limit the possibility that this will spark an idea in someone else’s head who has the wherewithal to act, to make, to contribute, to change. To me, I’m a cog in a very complex machine. The wings of a butterfly flapping can affect a tornado, that proverb. It’s like my son—I introduced him to Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of The United States when he was fifteen. He got the right book at the right time. He sees the government for what it is, sees capitalism—especially late stage capitalism—for what it is. Just by leaving a book around and saying, “Hey, you should read this sometime” and walking away.

SN: I feel similarly about people. Merely being in contact with people who I admire and love has a similar effect to finding the right book at the right time.

TG: Nice. Well played, well played.

SN: I know that when I go back to my studio your energy will be with me to write, to make my work, to challenge limitations when wanting to construct a piece and thinking, “I’m just this immigrant queer, why would anybody care what is happening on the other side of the world where they’re killing all these women?” But then I’ll say, “Well they have to know.” They have to know so they can bring any potential to change things back with them into their lives—

TG: So it’s not invisible. We try to make things visible, so that they don’t disappear. I think the worst is when history disappears—it needs to be a record in presence.

You make the bridge, a connection to humanity—when it connects. That’s why I wanted to use more than just Black, African bodies, and started using South Asian bodies. Also, I wanted to say, “No, colonization is much broader”—it’s happening to many different peoples of color. That opens it up to the idea of power, and how hegemony—this uncontested, overwhelming power—affects everyone. So I can start by localizing it, first, in how it affects me, then localizing it by how it affects others in my sphere. Maybe somebody else can see it from these different perspectives and understand how these hegemonic forces are operating on them as a subject of power.

Don’t undervalue yourself—which I’ll segue back to the Guggenheim fellowship.

Part of being Black, or part of my neuroses as a result of a colonized mind, is that I used to be under the impression that most people think that I’m not as intelligent as they are, and that most people think I’m less than. In a small way, you start buying into it, or the possibility of that affecting your behavior, and how you think of self. I was able to afford college and everything because I was a music photographer, a pop culture photographer, and I’ve always had this feeling that in the back of many people’s minds they think of me as a pop culture person who worked with Michael Jackson and not a serious artist—which is in my head because most people will answer “No, no, no, you’re a very serious artist.” [laughs] But that’s a distorted filter I have.

After the Guggenheim and that stamp of approval, I realized, “If this institution is giving me this grant, they’re also saying ‘no, no, no, you’re very serious’ and you’re using pop culture to critique culture.” That made me own who I am, made me own my history, made me say “Yeah I guess I was MJ’s photographer, but it’s not just about that.” It’s not about celebrity, you know, I’m just using that as a way to critique colonization, and my position in the African diaspora. I’m using the most famous Black body on the planet to talk about Blackness, and diaspora—and they [Guggenheim Foundation] understood it, and the Rockefeller Foundation understood it.

I don’t apologize inside. I say “Oh, you know what? Don’t believe the hype. Don’t believe that people think you’re not serious.” I drop that. My work is significant, my work is important—I don’t think I respected my work enough, but now I do.

SN: Do you feel that’s something that you’ve shed and now you can just leave behind, or is there a constant reminder?

TG: These are patterns, habits of thought—they don’t just disappear. But when it comes back, I have a swatter. I can just knock it off. It’s good.

Portraits, 2018, Install view, © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

[1] Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 36.

[2] Stuart Hall, “The question of cultural identity,” in Modernity and its Futures, eds. Stuart Hall, David Held, and Anthony McGrew (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press in association with the Open University, 1992), 277.

All images: © Todd Gray, 2019. Courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.