Closed Circuits: A Look Back at LACMA’s First Art and Technology Initiative

by Catherine Wagley

Julius Shulman, “Allison and Rible, Rand Corporation (Santa Monica, Calif.), 1962” © J. Paul Getty Trust

It was 1969 when artist John Chamberlain decided to screen his film The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez in the RAND Corporation’s cafeteria. The artist, middle-aged and best known for the smashed-metal monuments he had been sculpting out of discarded car parts, was having a Warholian moment. He had even cast regulars of Andy Warhol’s Factory—scrawny, always smirking Taylor Mead and wispy Ultra Violet—as stars of The Secret Life, which he filmed in Mexico in 1968. Mead plays Mexican conqueror Hernando Cortez and cavorts, making treaties and wreaking havoc. Ultra Violet, taller than Mead and far more conventionally attractive, plays his mistress, urging him to privilege sex and vanity over duties such as fighting for his people’s freedom. At one point, a mountain lion eats an antelope on-screen.

The film ran once a day for three days. Then all screenings were canceled. “Word must have gotten to Washington, D.C., that RAND was showing dirty flicks on lunch hour,” Chamberlain wrote in a memo to curators at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, though it seems staff complaints, not politicians, were to blame.

Chamberlain, usually based in New York, had a sparsely furnished office at the Santa Monica–based defense consultancy through LACMA’s Art and Technology initiative. “[This] hair-raising idea,” as curator Jane Livingston would call it 43 years later, involved pairing, or attempting to pair, 67 artists with corporations so that the artists could collaborate with company scientists and engineers.1Maurice Tuchman, the first chief curator of modern art that LACMA ever had, instigated the plan soon after leaving his position as a research assistant at New York’s Guggenheim Museum and moving to Los Angeles in 1966.

To the 27-year-old curator, the city, home to aerospace and plastics, seemed intoxicatingly full of potential and he felt that “companies might benefit immeasurably, in both direct and subtle ways, merely from exposure to creative personalities.”2

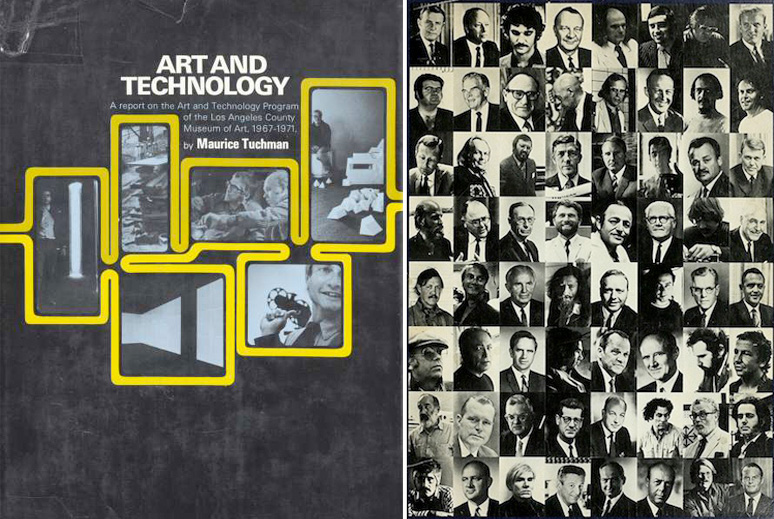

“A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971.”

If you have spent any time with the 392-page report that resulted from the Art and Technology initiative, you know that it contains little evidence of completed artwork. It’s an unwieldy record of an art museum’s Tower of Babel, a project so ambitious and optimistic it absolutely had to fail. But at least in retrospect, the report is refreshingly candid. Tuchman discusses setbacks, including how sculptor Claes Oldenburg refused to sign the contract. “[Oldenburg] is possessed of a forensic acumen that makes attorneys—including his own—envious,” the curator writes in his 12-page introduction, before outlining the entire back and forth in which Oldenburg worries about compensation and about art being co-opted for corporate advertising purposes.

Tuchman also notes how French artist Jean Dubuffet, nearly seventy and an institution in his own right by then, resisted ceding control of any detail of his work with the American Cement Corporation and discusses the “ironical attitude” Andy Warhol took toward machines in general. It seems the rockier outcomes of his expensive, drawn-out project genuinely intrigued the curator.

Even though Tuchman failed to include a single female artist in the Art and Technology effort and conflated technology with the corporate fairly uncritically, there’s still something charming about his disinterest in polish and his lack of discretion. (At one point, he says company reps can be “lugubrious.”) The sponsor here is as much something to experiment with as art and the artist.

So when LACMA announced a revival of the Art + Technology Program in December 2013, the possibilities initially seemed thrilling: an artist who’s concerned with surveillance installed at Facebook? An artist with a DIY aesthetic installed somewhere futuristically slick, like SpaceX? But current museum director Michael Govan explained that the museum had “updated the program to encompass the entrepreneurial spirit redefining so many industries,” and this called to mind the kind of strategic creativity Wired likes to cover (e.g., augmented reality obelisks or strange storytelling apps).3 It also quickly became clear that there would be more careful management and planning from the start—none of those “give Chamberlain an office at RAND and see what happens” stunts.

Artists would neither be invited nor paired with corporations before any set plans were made, unlike the first time around. (Tuchman had preferred that artists and companies come to each other with blank slates.) They would apply by making proposals, and selected artists could choose which, if any, partner company might help them achieve their own goals. Instead of working in corporate offices, their base would be the Art + Technology Lab in the just-renovated Balch Art Research Library in the museum’s basement.

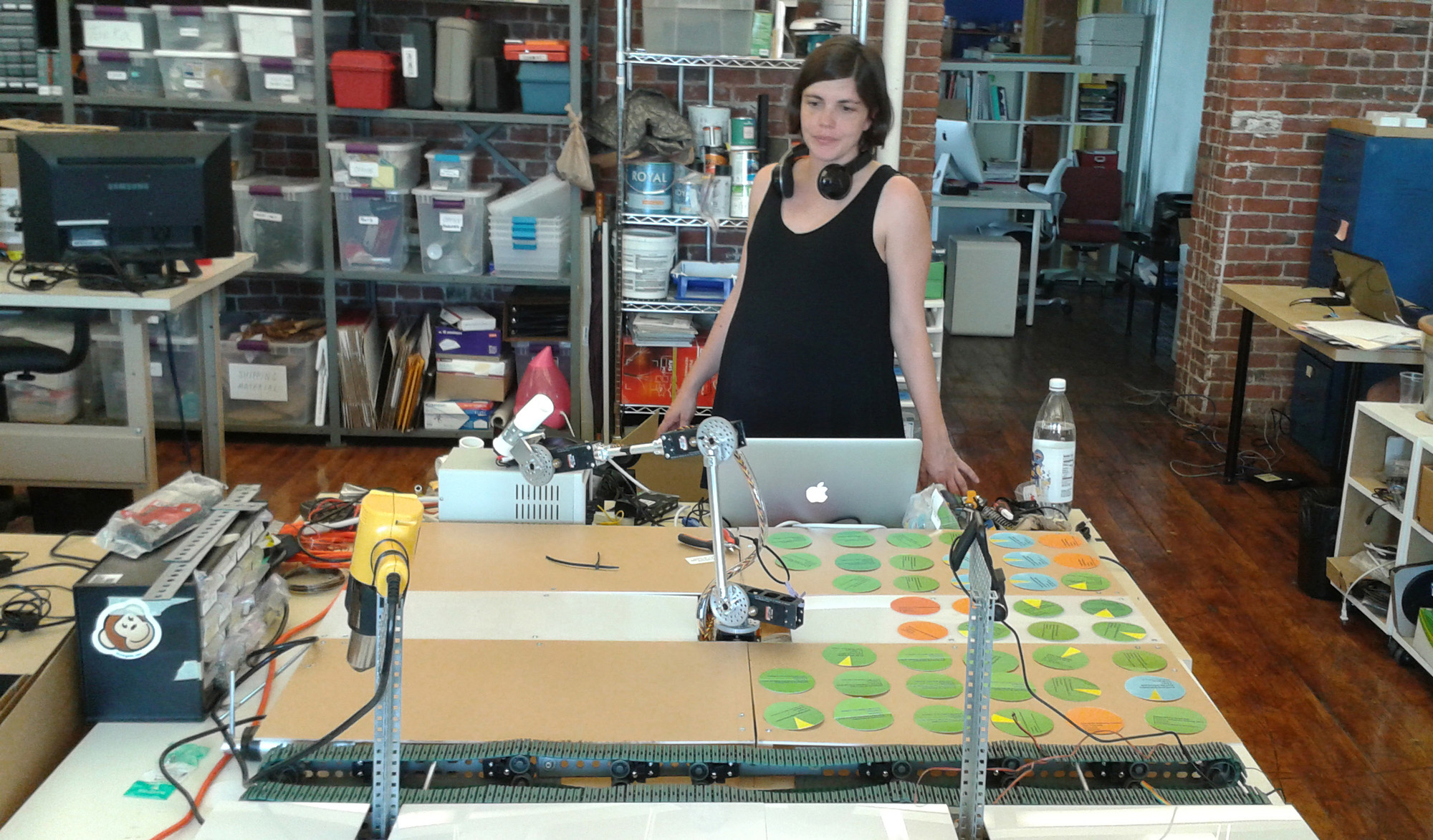

LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab in the Balch Art Research Library

By January 27, 2014, 450 proposals had been received. By April 9, Amy Heibel, the museum’s vice president of technology, Web and digital media, had sifted through the proposals with the help of contemporary art curator Franklin Sirmans and Govan, narrowed down the list, consulted with corporate advisors, and announced their six grantees. None were from Los Angeles. Most had already done work in their area of tech-related interest.

Granted, this sounds much savvier than the wide-open Tuchman approach. But the nostalgia for Art and Technology has much to do with the way the report suggests a moment when institutions were less careful about protecting their sponsors, when conflicts of interest could be openly discussed, and when a curator could publish pages and pages detailing how various collaborators did and did not get along. All this is especially appealing at a moment like now, when it’s hard to tell where one group’s interests end and another’s begins. In autumn 2013, when artist Doug Aitken launched Station to Station, a Levi’s-sponsored cross-country art project on a train, the teams of assistants belonging to the artists and those belonging to the brand were often indistinguishable. During the Museum of Contemporary Art’s odd 2012 collaboration with Mercedes-Benz, an exhibition curated by Mike D from the Beastie Boys, it was hard know what was art and what was advertising gimmick—the new Mercedes in the back gallery, the one with the doors you could open under security guard supervision, had to be the latter, right? Would the revised Art + Technology Program edge toward a similar blurriness?

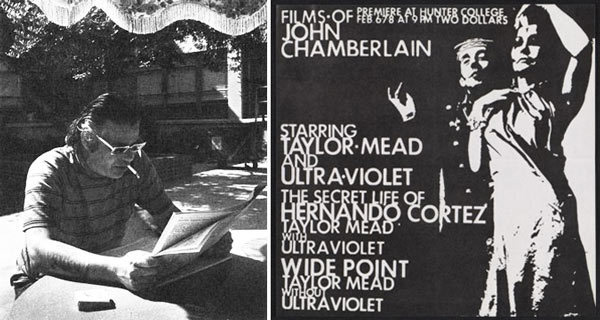

Left: Chamberlain at RAND. Photo © Barbara Crutchfield, courtesy of LACMA archives. Right: Flyer for a screening of films by John Chamberlain, Feb. 1967. Leo Castelli Gallery records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Chamberlain had been at RAND for about a month when Barbara Crutchfield photographed him there. In one image, the 47-year-old artist’s graying hair is almost long enough to touch his shoulders. He wears sunglasses and smokes a cigarette while reading the paper. According to a computer specialist at the corporation, this was a common scene. Chamberlain “installed himself in the office … or out on a patio with a tape recorder and let a few anointed come to him,” the specialist said. “Not many people came.”4

Chamberlain saw it differently. “I can’t get into any of their circuits,” he wrote in a memo to Livingston, then a young associate curator at LACMA.5 By “circuits,” he meant the attitudes and interests of the RAND employees. He felt that a certain uptightness kept them from engaging with him. “They’re very 1953,” he said in that same memo. “You know, like the girls wear too much underwear.”6

RAND had been among the first companies Tuchman thought of when planning for Art and Technology. When its executives agreed to participate in mid-1968, almost a year into the project, Brownlee Hayden, assistant to RAND’s president, wrote to Tuchman, “RAND has something special to offer the creative artist: an intellectual atmosphere and the stimulation of being amid creative individuals … the artist may find influences.”7 As other corporate partners would, Hayden seemed to assume artists needed “influence,” or inspiration, above all.

Every corporation that participated in the original program would be a sponsor in some respect, providing funds or certain services and getting its name and logo on LACMA’s publicity and exhibition materials. Straightforward sponsors such as RAND would host an artist and fund his (there was no “her”) efforts but would make no additional donation to the museum. Patron sponsors would donate at least $7,000 to the museum, in addition to taking an artist in residence, and would potentially receive an artwork in exchange for their support. Three companies—Pan Am, Times Mirror, and North American Rockwell Corporation—would underwrite the program as benefactor sponsors, donating money or resources to the museum in lieu of hosting an artist.

Sponsors of the original Art and Technology Program at LACMA.

“In reviewing modern art history,” Tuchman reflected in 1970, “one is easily convinced of the gathering aesthetic urge to realize such an enterprise as I was envisioning.” He cited Italian futurists, Russian constructivists, and Bauhaus artists who wanted to unify art and manufacturing, though he failed to mention Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which Billy Klüver, Robert Rauschenberg, and others had launched just before his own program did. “A need to reform commercial industrial products, to create public monuments for a new society, to express fresh artistic ideas with the materials that only industry could provide—such were the concerns of these schools of artists, and they were announced in words and in works.” But, he continued, “no intensive effort was made directly to approach industrial firms in order to harness corporate machinery or technology.”8

Certainly, before Art and Technology, no museum had tried to harness the technology of so many firms at once. Two hundred and fifty firms would be contacted; 37 ultimately participated. Tuchman said he imagined artists moving around those corporations as if in their own studios.9

In May of last year, when all six of the new Art + Technology grant recipients gathered in LA for an orientation, they visited the headquarters of five corporate sponsors: Google, SpaceX, Accenture, Daqri, and Nvidia. A representative from each of these companies, which will offer in-kind support to the grantees, sits on the program’s advisory board. The grantees also visited NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab at the California Institute of Technology, where artist Dan Goods, one of the two nonsponsoring advisors on the advisory board, works as a visual strategist.10

At SpaceX, artist Tavares Strachan, who initially proposed to launch glass rockets, posed in front of a Mars-bound capsule with the space transportation company’s chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell. Shotwell also came up to the LACMA lab to meet one-on-one with the artists, as did Sheri Wenker, managing director of communications at Accenture, the tech consulting company that took over administration of HealthCare.gov early last year. Specifically, Wenker has been speaking to New York–based Annina Rüst about data and sourcing.

About two years ago, Rüst debuted a robotics installation, similar to the one she proposed for this project, in Switzerland. A user would use a computer monitor to select a certain pie chart from a database, then place a premade pie on a conveyor belt so that a robot could put the selected pie chart onto it. Her revised version will do the same, though the new pie charts will specifically address the dearth of women in the original Art and Technology Program and in art and tech fields in years since. She has written a blog post about her thinking for LACMA.org, updated her website regularly, and hosted a few public pie-making sessions because pulling the public into the process is one goal of the new Art + Technology Lab. Neither the blog post nor Rüst’s website mentions interactions with Wenker or any other corporate advisors, but both suggest that the project has progressed nicely.

Annina Rüst in her studio © Annina Rüst

Only fifteen or so of the original corporation-artist Art and Technology pairings would result in something tangible enough to exhibit. The RAND-Chamberlain pairing was not one of them. Maybe because of this, Chamberlain’s biographies and monographs barely mention his episode with the corporation.11Why dwell on an anomaly?

Chamberlain’s name had come up in staff meetings at LACMA a few months before April 1969, when Livingston, visiting the East Coast, stopped by his New York studio. Though he had been making stand-alone sculptures of scrapped metal for at least a decade by that point, Chamberlain had gotten caught up in a performance-friendly 1960s moment. He wanted to make environments of sculpted objects and shoot a slow-moving, steamy art film in New Mexico. When Livingston invited him to propose some ideas for Art and Technology, he initially wanted to film in all fourteen towns on the US’s 42nd parallel and to play the resulting footage simultaneously on multiple screens. This is what he discussed when he came to Los Angeles in May to meet with researcher Dr. Charles Spitzer at the Ampex Corporation, a company that developed radio equipment. Bing Crosby, who disliked live broadcasting, was an early adopter of its prerecording gear.

Ampex had already had complicated meetings with other artists, including Hans Haacke, who had spent two days with Spitzer the month before. Haacke, still mostly known as a sculptor (and not yet for exposing museums’ problematic financial allegiances) spoke to the scientist about a project tentatively called Environment Transplant. Haacke wanted to attach a camera to the top of a van that would be on a rotating disc of some sort. The camera would turn, recording everything around it as the van drove around the city. The footage would then air live at the museum, where, in a cylinder-shaped gallery that would have to be specially built, a projector would spin on top of another turntable.12

The idea excited Spitzer, but there would be FCC permits to procure and a van to rent for the whole four months of the exhibition, among other complications. In the end, as Livingston wrote, “Ampex did not want to assume responsibility for solving any of these problems.”13

Ampex reps would also meet with Michael Asher, Jules Olitski, Robert Morris, Francois Dallegret, Les Levine, Otto Piene, Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, and Fred Eversley between 1968 and 1970 and determine most were simply asking too much. They felt Asher, who wanted to create a light that floated in space and had an “elusive” or “happened upon” quality, was asking them to implement unknown phenomena and was thus being unreasonable. In Chamberlain’s case, it was he who rejected them. “[He] was left with a feeling of ambivalence, if not indifference about seeing through a project there,” Livingston explained in a memo after the artist’s meeting with Spitzer.

Next, curators took Chamberlain to tour the San Fernando Valley laboratories of the drug company Dart Industries, where employees made inhalable medicines. On the drive from LACMA to the labs, Chamberlain imagined packaging odors that museum visitors could inhale. When he arrived, he discussed the feasibility of this with an inorganic chemist, Francis Petracek, who thought this could indeed be done and that Chamberlain could even package the scent of a location like Tokyo. But Livingston and Tuchman worried that traveling with a technician to capture the scents of foreign cities would be beyond the scope of Dart’s financial commitment and capabilities, so were unsurprised when the company’s interest fizzled.

The artist then left for a month to shoot his film in New Mexico—which became a series of vignettes called Thumbsuck, starring the striking artist and occultist [Marjorie] Cameron—while Livingston worked on setting up a meeting between him and the Irvine-based International Chemical and Nuclear Corporation.14While on location, Chamberlain compiled a list of potential scents (the ozone, downtown Las Vegas, the American flag at Camp Pendleton, Max’s Kansas City) for the odor-packaging project he had begun calling SniFFter.

International Chemical showed little interest in his ideas, but the RAND Corporation had expressed interest in taking on a new artist.15 Its previous artist in residence, Larry Bell, known for his colored-glass boxes, had not worked out. (Later, Bell said he felt RAND’s attitude toward him had been “let’s all pitch in and make something for the patio.”)16 In Livingston’s words, “a great deal of mutual bafflement prevailed” during Chamberlain’s initial meeting with RAND administrator Robert Specht. But this did not stop RAND from offering the artist an office “to use as he saw fit.” Chamberlain set himself up there, proposing projects such as group portraits on the patio. Months of further bafflement ensued. “I’m not pretending to be some sort of psychiatrist at RAND,” the artist wrote. “But I’m there, and I’d like to deal with them.”

Installation photo of Öyvind Fahlström’s Meatball Curtain, 1970 © 2015 Öyvind Fahlström / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Germany. Photo © Museum Associates / LACMA

From the time Mrs. Otis Chandler, the philanthropist whose husband owned the Los Angeles Times, provided the initial financial backing in 1967 to when the original “Art and Technology” exhibition opened at the museum in 1971, the Chicago Democratic National Convention riots, the My Lai massacre, the Kent State shootings, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy had all happened. Indefatigable artist Judy Chicago had her feminist awakening, started the Feminist Art Program in Fresno, and then moved with it to CalArts during those years, too.

Chicago joined the ad hoc Los Angeles Council of Women Artists, a group of feminists, in protesting the museum in 1971 because Tuchman had engaged only one woman, Channa Davis Horwitz, in the Art and Technology Program, briefly recounting her ideas in the report though she never even met with any corporate representatives.17They issued a letter: “The ‘Art and Technology’ show has been heralded as ‘the wave of the future.’ If this is so, then we are most distressed … but not surprised.”18

Artist-critic Max Kozloff eviscerated the “Art and Technology” exhibition and program in an Artforum review titled “The Multimillion Dollar Art Boondoggle,” writing, “Thus, finally, the two parties, the artist and technicians of society, were brought together in a long-hoped-for union, only to produce a folie à deux.”19Critic David Antin, who had been an early supporter of the show and was even in talks with Viking to author a book about the project, ended up writing only a frustrated 1971 essay on the endeavor for Art News. “This is the age of the conglomerate,” he explained, suggesting that Tuchman had not quite understood how corporations work. “Technology is corporations. This is a straightforward sociological definition of technology as enclaves of social and economic power.”20Like Kozloff, Antin found Tuchman’s failure to address the political implications of this and other aspects of the show inexcusable.

But Kozloff, who found the derisive mode in which so many artists such as Chamberlain ended up producing work frivolous at the time, has changed his mind since. “I now think that such derision was indirectly critical of the whole enterprise,” he said decades later. “It was the way for them to go.”21The artists, with their impossible and impish proposals, were butting up against the “enclaves of social and economic power,” in some cases with impressive persistence.22

Chamberlain was among the most derisive of the Art and Technology participants. After his initial attempt to engage RAND employees in conversation failed, he started issuing proposals: Maybe RAND should cut off the phones for a day, or maybe he could take a large-format photograph of RAND’s headquarters, then airbrush the building out, leaving only the Santa Monica surroundings.

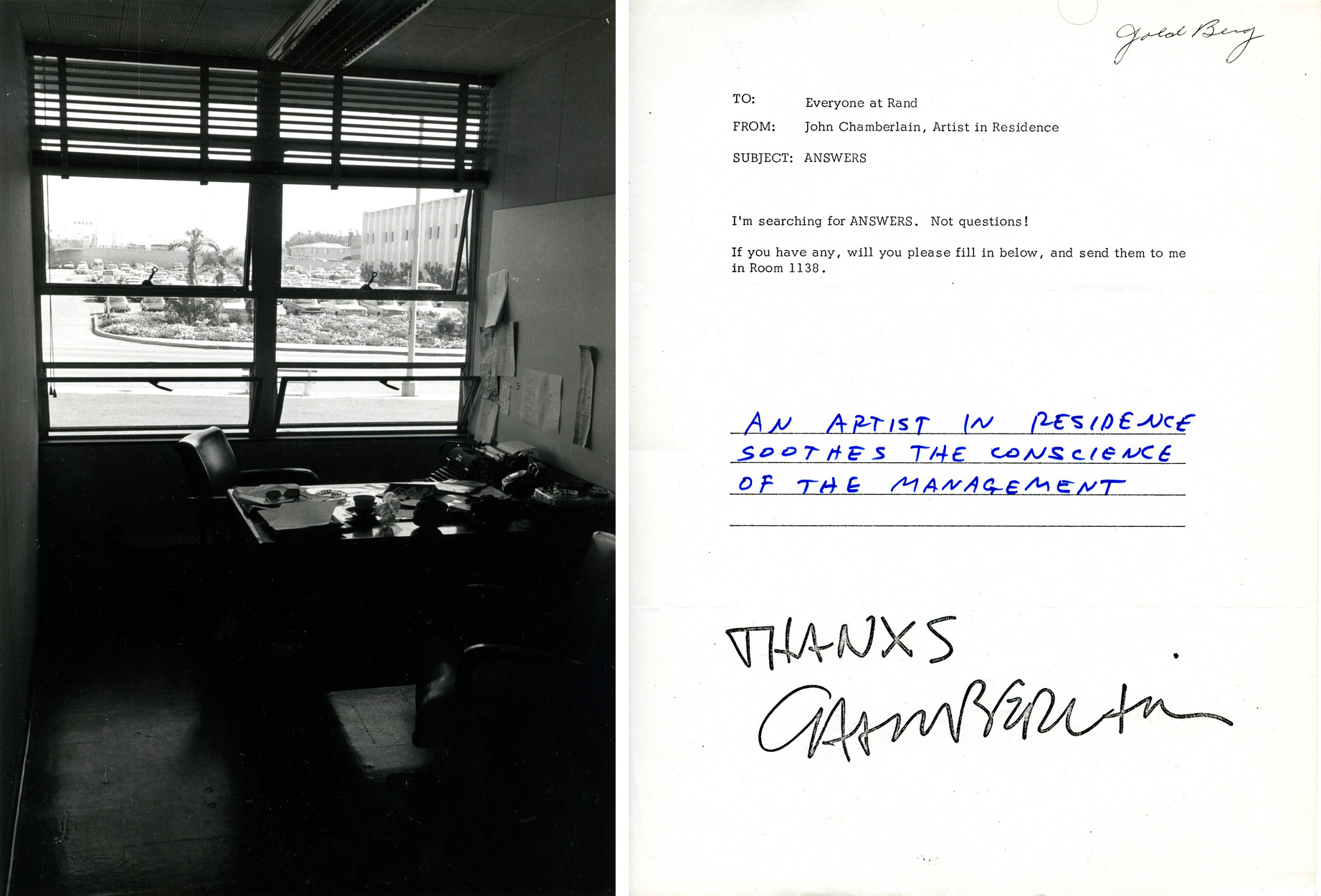

After these proposals and his screening of The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez failed to engage his corporate audience in the way he wanted, he initiated his “I’m looking for answers” campaign. He asked RAND employees at all levels “for ANSWERS. Not questions!” He vaguely took his inspiration for this from James Lee Byars, the only other Art and Technology artist working with a think tank. Byars had been asking intellectuals at the Hudson Institute for questions, not answers, and Chamberlain imagined joining his answers (not questions!) with those at some point; but he also just wanted to compel free association in a place that privileged what he saw as unadventurously linear thinking.

Left: Chamberlain’s office at Rand. Photo © Barbara Crutchfield, courtesy LACMA archives. Right: A questionnaire seeking answers sent to the employees of Rand Corporation by Chamberlain as part of his Art and Technology piece, Rand Piece, 1970. Copyright: © 2015 John Chamberlain / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Museum Associates/ LACMA

A few employees played along, writing answers about Newtonian physics or how Ray Charles was God. Barney Meyrowitz from the mail room was especially enthusiastic: “You are what you are, not better no worse! But keep Punching—” A fair number of others were unambiguously hostile. “An artist in residence is a waste of time,” read one unsigned response. Another suggested a question before giving an answer: “? – What can you do for RAND. Ans: RAND can do without you.”23Wrote a third, in all caps, “THERE IS ONLY ONE ANSWER: YOU HAVE A BEAUTIFUL SENSE OF COLOR AND A WARPED, TRASHY IDEA OF WHAT BEAUTY AND TALENT IS.” And another: “The answer is to terminate Chamberlin [sic].”24

This understandably annoyed the artist. “I would have liked maybe to use the answers to express a viewpoint about RAND people in terms of their intelligence,” he told Livingston. “Because I’m not so sure about it. I mean, I see people who speak Spanish and [then] misspell simple words and have sort of dumb fifth-grade attitudes about everything.”

After Chamberlain’s residency quietly ended in 1970, Livingston conducted a follow-up survey at RAND. A sympathetic communications consultant observed of her peers, “It was difficult for them to see John as a provocateur, an eccentric, a seer—people couldn’t make the leap out of conventional discourse into his imaginative world.”25In other words, they couldn’t get into his circuits, either.

When the new Art + Technology Lab ends its first year, the correspondence between the artists, the museum, and the corporations will be collected and published in a Web-ready report, along with documentation of each project’s progress. This means, probably, that this correspondence is being written with an eventual public at least partially in mind; and right now, the main people the lab artists are “dealing with” are members of that public—each artist has hosted or will host a public program of some sort, as have a handful of invited artists who are tech-involved but not grantees.

On September 11 in the LACMA Lab, artist-filmmaker Miranda July spoke to a small crowd about her recent, characteristically quirky project. She is not a grantee, but her project, an app called “Somebody,” is an art-tech hybrid. The app works like this: You send a message, which goes to somebody who also has the app and is in the vicinity of the message’s intended recipient; that person then delivers it verbally and in person. July had thought of the idea and struggled to figure out how to make it a reality for months before Miu Miu, a subsidiary of the fashion house Prada, asked her to make a short film to show at the Venice Film Festival. The film was supposed to include a cast of women wearing mostly Miu Miu clothes. July broke these rules, making a film in which a big black man working out at a park verbally delivers a break up text to a wimpy white guy picnicking by himself and a waitress delivers a marriage proposal to a woman eating alone. Every character is a stereotype but intentionally endearing.

Miu Miu gave July initial support but did not help her with the actual app-making, which, unsurprisingly, proved complicated. She ended up enlisting the company Stinkdigital and calling lots of tech and business people for advice on a venture that’s still unwieldy and glitch filled even though it launched officially on August 29. Glitches or not, in certain areas, like the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, there were a surprising number of committed early adopters. “A real Paul Revere,” someone commented in the app’s rating section, after a guy delivered a message while on his morning jog. It’s all very DIY.

Half a century ago, Chamberlain saw the Art and Technology Program mainly as a chance, not to make something, but to butt up against a world with different goals. “I’m initially interested in anything I don’t know about,” he said in his post-residency follow-up interview with Tuchman. “I’m interested because I need something to lean on.” Trying to enter a new system was like working with new material. But maybe when the first year of this new Art + Technology initiative wraps up, the more interesting aspects of the report that’s released will be those that show what artists choose to do themselves and how they access the technology they need without aligning themselves with corporations, not even trying to “get into the circuits” of a world they know has different end goals than they do.