The Jack Box Death Trip: How Ads Promote Progressive Values from Plate to Altar While Still Making Everybody Rich

by Travis Diehl

It’s not fine art, it’s applied art. It’s the difference between sculpture and architecture. Sculpture can be just about anything, but architecture has to be something you can live in and work in. —Dick Sittig1

“Am I trippin’? Or is that Jack Box?” You’re not tripping. It really is him. But you’re right about another thing, too: This thirty-second TV spot really is about being high. Of course, the message is thinly coded. It’s only 2012, after all, and as far as the feds are concerned, marijuana is still a Schedule I substance. No—as the camera slowly stumbles around a group of college kids munching fast food on a grassy quad, they say how “loaded” they are. The commercial promotes, ostensibly, the Jack in the Box chain’s new “loaded breakfast sandwich.” “Country sausage, fried egg, bacon, melting cheese…” Yet it’s the subliminal genius of agency Secret Weapon Marketing to exploit the inherent trippiness of the chain’s mascot—a crisply dressed businessman with a round, white, unblinking clown head—finally, some two decades into his signature campaign, acknowledging the druggy improbability of his existence. Beyond announcing a new configuration of meat and melting cheese, the ad positions Jack in the Box as not only in on the joke—that is, hip to its major late-night market—but as, in retrospect, having always been the more “turned-on” of its competitors.

It’s been nearly a century since advertising discovered the power of irrational appeals—a moment that might be traced to ad man Edward Bernays, who, among other propaganda coups, famously convinced Americans that bacon is a breakfast food.2 An overreach of media-delivered influence? Sure. Jack gets it. Bernays also successfully portrayed cigarettes as “torches of freedom” in order to encourage women to take up the habit—a tidbit possibly stuck in the minds of the ad creatives as they wrote a 2006 spot in which a doctor tells viewers that Jack in the Box’s deep-fried stuffed jalapeños and bacon potato wedges will prolong their lives.3 “Furthermore,” says Doc, “I believe bacon prevents hair loss.” “Where did you find this guy?” says Jack. And his associate: “tobacco company.” Big wink of those unblinking eyes at the viewer, who (Jack would have you believe) is too smart for the usual tricks. Some unusual ones are in order, then—as represented by such abstract triggers of desires divorced from the product per se. Whereas a commercial as recent as 1993 compared Jack in the Box food to that of other chains based on its evident merits (the tagline for an early ’80s campaign was “There’s No Comparison”), today, couched in a virtuosic display of offbeat yet poignant cultural signifiers, the food makes only a fleeting factual appearance.

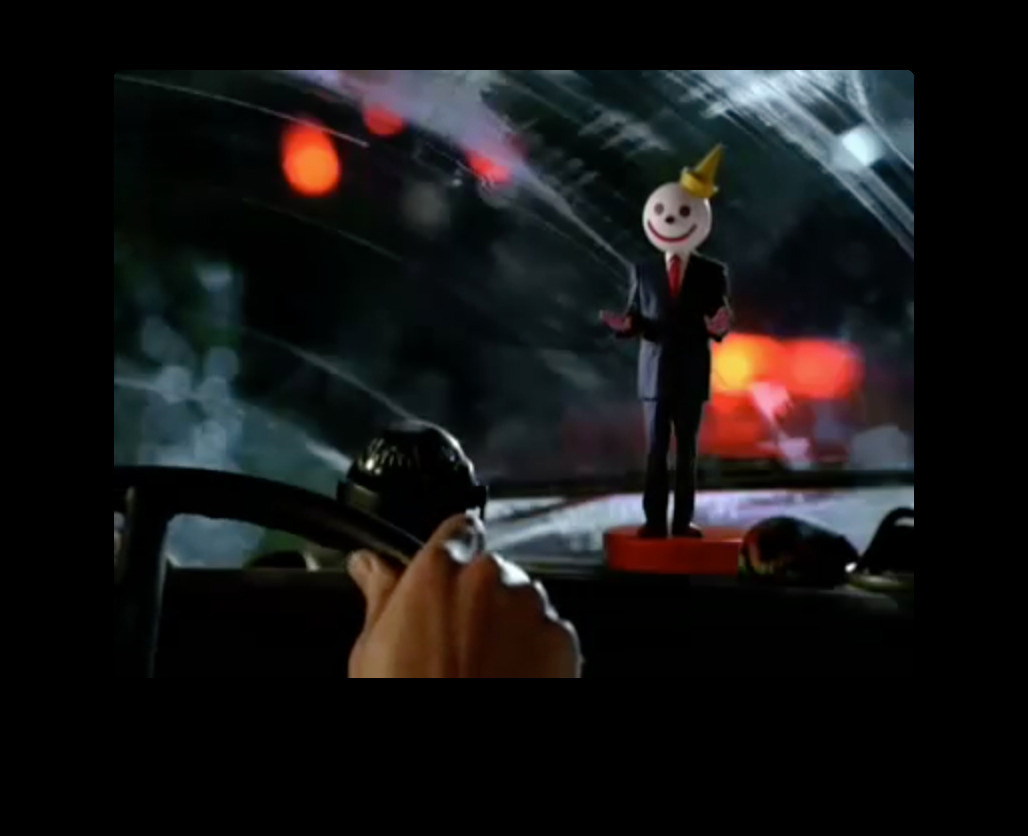

How can a burger chain such as Jack in the Box—as of this writing, the country’s sixth largest —get away with marketing that is not simply risqué (à la Axe products) but of debatable legality in many states?4 But marijuana isn’t quite as illegal as it used to be. In 2003, California enacted Senate Bill 420, which codified the implementation of its earlier Prop 215 Compassionate Use Act of 1996—effectively establishing the present quasi-legal medical marijuana dispensary system.5 San Diego County, home to Jack in the Box HQ, resisted the measure in the courts until 2008; yet Jack lost little time wooing a demographic gradually entering a smoky gray limbo. The earliest example of what we might consider a weed-themed JitB ad, in which a clearly intoxicated young dude is helped at a drive-through by an hallucinated Jack Box figurine on his dashboard (a throwback, perhaps, to its clown-headed intercom of yore), appeared in 2006. In a 2009 version of the ad, a visibly high kid in a vintage van tries to order 99 tacos for two cents. The figurine helps him out. “Psst. It’s two tacos for 99 cents.” A just-say-no parody featuring “Larry the Crime Donkey” ran as early as 2003.

Like liberal attitudes toward psychoactives, fast food is quintessentially Californian. The first McDonald’s opened in San Bernardino in 1940, Taco Bell in Downey in 1962, Carl’s Jr. in Anaheim in 1956, and In-N-Out Burger in Baldwin Park in 1948.6 In 1951, Robert O. Peterson opened the first Jack in the Box in San Diego. The story of fast food is one of entrepreneurship and progress, homogenization and ruthless expansion—the two sides of the corporate coin. Little wonder that its most radical innovations, not just in food but in its delivery vectors, arose where cultural manifest destiny meets the psychic oceanic. Witness: waitresses on roller skates, drive-through windows, and Jack’s first incarnation as an innovative two-way drive-through intercom. “Jack will speak to you,” said the signs. No, you’re not tripping. Jack Box appeared in this form until 1980, when a controversial ad (for its day) showed Jack in the Box execs dynamiting the clown—a first desperate rebranding, a warning, directed at fans of Ronald McDonald and his ilk, that Jack in the Box was no longer just for kids.

Indeed, this was only the first of Jack’s near-death experiences—and a prelude to the company’s darkest episode. In January 1993, an E. coli outbreak traced to undercooked Jack in the Box patties killed four children in the Seattle area and sickened more than seven hundred people in Washington, California, Nevada, and Idaho, many with permanent organ damage.7Steep discounting and a valiant PR effort couldn’t stop the hemorrhage. Fighting for survival, JitB sought a solution in advertising.8They hired Dick Sittig, then at ad firm TBWA/Chiat/Day; by 1997, Sittig was on his own, founding Kowloon Wholesale Seafood Company in Santa Monica, California—now known as Secret Weapon Marketing. Jack in the Box was his first client.

Today the “Jack’s Back” ad campaign is among the longest running and most awarded in history.9The Effie organization granted the campaign a silver medal for Sustained Success in 2006, acknowledging that

In 1993, the Jack in the Box brand was on the verge of bankruptcy after being linked to the largest and deadliest E. coli outbreak in American history. To bring back the brand, advertising was the primary weapon employed to save the company.“10

Secret Weapon website offers this blunt synopsis on its website:

In 1993, a food poisoning outbreak traced to a Jack in the Box restaurant in Seattle resulted in the deaths of four people. Jack in the Box’s business came to an abrupt halt. After a year and a half of severe discounting and unrelenting bad press, sales had not recovered to pre-crisis levels and earnings were so poor the company came close to bankruptcy. … We launched the Jack campaign in 1994. Sales responded immediately, and Jack in the Box has not only recovered but thrived. So much so, that the campaign continues today and is one of the longest-running advertising campaigns in history.11

“After suffering huge losses in 1993 and 1994,” writes Jeff Benedict in his chronicle of the E. coli outbreak, “Jack in the Box saw sales spike up in the first quarter of 1995. The uptick was the result of a new television ad campaign featuring a character named Jack the CEO, who wore a clown head.”12 To move the restaurant past an unprecedented food poisoning nightmare, Jack in the Box needed some of fast food’s ballsiest, most id-infused ads.

The campaign has ruffled feathers from the start—not only because of its teen-targeted irreverence, but also due to an eerie referencing of current events. In the very first spot, Jack Box—now reincarnated “through the magic of plastic surgery” in his current form as the chain’s ball-headed founder and CEO—walks into company headquarters and kills the sitting board with a bomb. The ad ran in December of 1994, “at a time when the news is filled with explosions and death—a suicide bomber in the Gaza Strip, a mail bomb in the suburbs of New Jersey, a fire bomber on New York’s subway.”13Not everyone found Jack funny—which suited him just fine.

The first “Jack’s Back” commercial is early evidence of Sittig and company’s ability to turn national malaise into a grown-up cartoon. Yet the crucial message was not exactly cultural; the ad purported to signify a change of corporate leadership, portraying a reinvented company that had learned the lessons of the horrendous outbreak one year prior. In fact, other than strict industry-altering beef safety standards at every point in the supply chain, very little had changed at Jack in the Box HQ.14The vice president responsible for overseeing food quality in ’93 now worked in the marketing division.15 Flesh and blood company president Bob Nugent remained in charge. But the company badly needed to destroy the impression that their out-of-touch leadership put profits above the lives of its consumers. “Even though it was all fiction,” Sittig told the Los Angeles Times, “people said, ‘Okay, I guess there’s a new guy running the place,’ and customers started coming back.”16What the “Jack’s Back” ad signified was not new leadership but a new era of branding—one, crucially, featuring product in only the most functional way, while weaving the Jack character into a universe uncannily in sync with ours.

In a 1997 spoof of Cops, Jack Box chases down and tackles a mulleted man who has “dissed his food.” Other spots poke fun at vegetarianism or the Spice Girls or even the 2008 recession.17Each quick cultural jab is integrated into the form of the fast food ad; the hook, the food, the picture of the food, the new Jack logo. A human hand clutches some type of glistening sandwich, as Jack’s sales pitch—voiced by Sittig himself—issues from his edgeless round head and unmoving mouth.

2012 saw Jack Box and company swing even further into the rapidly mainstreaming regions of the cultural unconscious. In a 2012 Super Bowl spot, which aired in February, a young man sits on a couch with his mother. “Mom,” he says, “I’m getting married.” “Who’s the girl?” “It’s not a girl…” And this moment, as that ad mother’s wholesome face slides into ill-looking shock, marks the divide between the right and the wrong sides of history. Sure, her son soon explains, face glowing: “It’s bacon.” The rest of the commercial veers into farce, as if to provide relief from an all too serious joke. They pick out a ring; he eats the bride. If you love it so much, why don’t you marry it? But the viewer knows, on one level or another, that love is not always enough.

In early 2012, only seven states recognized same-sex marriage. California’s Prop 8, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman, passed in 2008 before being repealed in 2013. Slippery slope arguments made by the likes of Senator Rick Santorum [R-PA, 1995-2007] and Fox News pundit Bill O’Reilly compared a gay couple to a man wedding a box turtle, a dog, and a duck.18One facetious argument deserves another: why not bacon? Jack Box knows which way the wind is blowing. Jack Box gets it. The “Marry Bacon” campaign was still going strong in March of that year when the “pro-family” comments of Chick-fil-A President Dan Cathy resulted in a slurry of boycotts and counter-boycotts of his chain.19No such fallout for the Box—a restaurant once again positioned ahead of the political curve.20

Yet the edgy currency of the “Marry Bacon” ad was not lost on a sophisticated public—even if the silly spot’s ambiguity left it open to attacks from both sides. Bloggers decried the commercial’s flip portrayal of a grave social issue.21 Washington Representative Mark Hargrove actually cited the mother’s pained reaction as proof that gay marriage must be stopped.22Others took the view that the ad belittles the battle for marriage equality. A Change.org petition asking Hulu to stop airing the ad received 46 of 100 needed signatures.23 Their beef? That the “homophobic” ad demeans gay marriage. Jack’s weed-themed ads, too, have raised their share of ire. Parents’ advocacy groups slammed the 2006 “Stoner” spot, not just for glorifying pot use but for showing a minor driving under the influence.

For its part, JitB claims only that its commercials are meant to be entertaining—all attitude, no critique. Gay marriage? Marijuana? Perhaps we might as well ask if Jack’s Cops spoof is a comment on the prison industrial complex. Or, as Sittig puts it, perhaps it’s simply that “young men eat a lot of fast food, and they like irony.”24 A Jack in the Box VP insists its recent Munchie Meals product is targeted at “folks looking for indulgent treats” between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m., not stoners.25 Of course, this would be easier to believe if the commercials didn’t feature speech-impaired kids on couches rapping with a Jack Box puppet. Each hand of JitB corporate seems, or would like to seem, ignorant of what the other hand is up to.26

Ambiguity and irreverence are staples of contemporary burger ads—though Burger King’s trippy “king” character and Carl’s Jr’s sauce-stained supermodels fall short of the clever cultural pirouettes performed by Jack Box.27 No surprise that JitB, like other late-night snack outlets, seeks cool points with stoners, but the directness of its pro-weed spots approaches an activist stance. Its campaigns’ main burger-selling program has political side effects seemingly detached from the personal beliefs of the individuals involved. The ads are humorous, true—it’s no accident that Jack Box is part clown—which lowers viewers’ rejection thresholds, diffuses criticality, and encourages a positive attitude toward the brand.28 But when more volatile concepts enter the marketing mix—not simply sex but drug law and gay marriage—the well-crafted and well-liked Jack spot is just as likely to signal, if not perpetuate, the mainstreaming of previously taboo ideas. “Goods help destroy stereotypes,” writes ad theorist Grant McCracken. “Goods are both the prison and the keys to the cell.”29

Bernays convinced Americans to eat more bacon. Has Sittig convinced us to marry it? Better to ask how many folks volunteered for Jack’s “Bacon-Infused” email list. Advertising is no longer so literal, and ads no longer logically generate demand. Referring to the early 1900s, cultural historian Jackson Lears describes “the complex relationship between power relations and changes in values—or between advertisers’ changing strategies and the cultural confusion at the turn of the century.”30 Ads and culture are no less confused today. Rather than persuade new customers, companies now attempt to win, and keep, their approval—a goal in fact displaced from the product itself. Jack in the Box made great strides in improving the safety of its meat, but it was advertising that saved the company. The chain’s death and rebirth follows the shift from the practical, copy-laden commercials of midcentury to the disembodied, irrational appeals of the present era. “When the consumer looks at ads,” writes McCracken, “he or she is looking for symbolic resources, new ideas, and better concrete versions of old ideas with which to advance their project.”31 Advertisers once manipulated desires to create demand; now ads offer a kind of complicity between companies and consumers, in which brand loyalty is swapped for culturally transmitted meaning. For its part, JitB can hardly be accused of pushing drug legalization or advocating same-sex marriage—only responding, in its own best interest, to the clearly a-changin’ times.

The food stays the same, yet Jack is always Back and better than ever. How is this possible? Jack put it best: “the miracle of plastic surgery.” That is to say, a good ad agency—one able to pivot almost unconsciously through contemporary culture, wielding, among other values, an almost mercenary acceptance of progressive politics. The mutability of topical ads keeps the brand linked to everything from vegetarianism to the housing crisis, legal weed to marriage equality. Yet it remains far easier to withdraw a “like” than a lifestyle. Irony here provides both parties with plausible deniability and an easy exit. In 2009, hit by a thinly disguised city bus as he crosses Hope Street in downtown Los Angeles, Jack Box slipped into a coma. The stricken CEO enjoyed a speedy resurrection—but not every child infected by his burgers was so lucky.

Shortly after filing the final draft of this essay, I was chatting with an Uber driver on our way to LAX. I mentioned I had been writing about Jack in the Box commercials. “Oh,” said the driver, “you know they just fired their ad agency.” I didn’t. The driver claimed to have a friend close to the events. Jack in the Box corporate, it seems, was displeased with Secret Weapon’s increasingly stoner tactics. It turns out these ads target an already willing audience while alienating more wholesome demographics—mothers, for instance. It made sense. But hadn’t the chain spent the last twenty years mocking the happy-burger-circus angle of its competitors? Why turn back now? I ruminated on the fallout of corporate’s decision all the way through security. Was the restaurant’s druggy gamble mostly Secret Weapon’s idea after all? Didn’t Dick Sittig’s company still somehow own Jack—or, at the very least, his voice? Did this spell doom for the progressive potential of this small but flourishing segment of mass media? Would love ever make more money than the love of money? At the terminal I did a quick Google search. Sure enough, multiple sources reported that David & Goliath, a larger LA-based ad firm, had joined the Jack in the Box agency roster. No public mention of Secret Weapon being let go, however—in fact, it will remain the chain’s lead agency—but the future of the campaign seems uncertain. D&G’s first effort, a Super Bowl product launch for the Buttery Jack line of burgers, features a distressingly mute Jack riding a motorcycle through macho Western landscapes. Easy Rider? Maybe. Brokeback Mountain? A stretch. Disappointing, then, but plausible, that two decades on from its near-death experience, the chain might decide to play it safe. If it’s true that Secret Weapon’s days with the account are numbered, I can only hope—as it moves to greener grow houses—that it uses its considerable power for less tainted forms of good.

Jack could not be reached for comment.