Countercultural Positions, Motherhood, and Reclaiming Craft as a Feminist Practice

by Cathy Akers

Installation view 1, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheelers Ranches Reconsidered, Lenzner Family Gallery at Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, February 2 – March 28, 2019.

In response to Cathy Akers’s exhibition, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranches Reconsidered, a panel discussion was held at the Broad Performance Space at Pitzer College on March 27, 2019. Chaired by Akers, participants included Micol Hebron, Claudia Parducci, Astri Swendsrud, and Jemima Wyman. Micol Hebron’s contribution to the discussion is not included in this piece; she decided that she did not want her comments published.

This is an edited record of that discussion, which ranged from utopian communes to the gendering of craft. Akers wrote the following introduction framing this re-presentation:

I have known Ciara Ennis, Director and Curator of the Pitzer College Art Galleries, for more than a decade and was thrilled when she invited me to have a solo show. We had met originally around 2007, during a studio visit shortly after I graduated from CalArts. Sharing an interest in utopian movements, she included me in a 2009 group show at the 18th Street Arts Center: LA 2019: Cults, Collectives, and Cocooning. She later included my work in Manifesto: A Moderate Proposal at Pitzer College in 2018.

It was Ennis’s idea to put together a panel discussion in conjunction with my recent exhibition and I am grateful for her encouragement. It was wonderful to reconnect with many of the amazing women artists whom I’ve known for years through this wide-ranging conversation about issues related to all of our practices.

*

Cathy Akers: Since this discussion is framed around my exhibition at the Lenzer Family Gallery here on the Pitzer campus, let me begin with a little background. For a time, I’ve been interested in the impulse to create a different society—a better society from the mainstream—the idea of utopia. In some ways that’s driven by a consideration of the difference between human nature and culture: what humans need to survive on a very basic level, versus the societal structures and laws evolved through time. My interest developed specifically from that tension between people wanting to have personal freedom but needing to cooperate to exist effectively.

I started researching communes about a decade ago, the formation of which has been a part of American history since the early 1800s, but I was particularly interested in the countercultural movement of the 1960s as the most recent period of widespread interest in communal living. I found two local ones, Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranch, through these amazing, extensive online archives.

I spent a lot of time online reading their stories, and through that process I got in touch with some of the original residents and was able to get to know them. I met with many who’d lived there and became really interested, specifically, in the stories of the women, and also the children, of these communes.

I wanted to find out the truth about their lived experience in these places, and if it really was a utopia, or if it was a more complicated situation. I learned that it was definitely the latter, and that these two communes in particular were not really interested in having any rules: they were concerned with people having unlimited personal freedom. You could do whatever you wanted. Anybody could come live there. Nobody was in charge.

I think the residents discovered that you can leave society behind physically, but unless you address that baggage you have from growing up within a culture, all that stuff is still going to be there, even if you believe you’re liberated because you live in a tent in the woods.

Because people didn’t really address their innate programming, the best and worst of their natures came to the surface in these communes. There were wonderful things that happened—people were together, were in harmony—but it was also a terrible place to be a woman. There was a lot of misogyny, a lot of racism, and a lot of disregard for children’s needs.

I wanted to imagine creating an intentional community without really thinking about intentions, which these places demonstrate. My purpose was to unpack this veneer of counterculture and really figure out what was going on behind it.

At this point I’d like to let the other artists talk about their own practices a bit, especially their projects in conversation with my show here at Pitzer.

Survival Tent, exterior, 2011; wood, tin, acrylic mirror, foam, muslin, foil insulation, canvas ducting, 72 x 72 x 84 inches

Claudia Parducci: (Indicating projection behind panelists) This is a piece I made about ten years ago. It’s a survival tent, and when I was looking through images deciding what to bring, I realized that with all of my work I develop these projects that go on for years, grounded by a structure of some kind, and then there are offshoots from that.

I made that tent when U.S. forces were in Iraq. It was the first time that I was really aware of our country being at war, and I found it disturbing. We started seeing these terrible images and it made me feel unsafe. Even though I could rationally understand I wasn’t in danger, it was scary.

So, I spent about a decade on this project, where I really explored the strategies people have for trying to make themselves feel safe in tumultuous times. And I went pretty far down that rabbit hole researching preppers—you know, people who build bunkers and go off . . . maybe not communes, but finding ways of living with or without others that they feel will keep them protected.

I built this survival tent, and I wanted it to be friendly, so it’s shaped like a gas mask, but it says “peace” on it.

All of my work concerns human conflict and cycles of constructing societies and destroying them, because that’s what we humans do: we build, and we tear down. I wanted to make a structure that was doing both at the same time for the next one, that could be seen as rising or falling, or somewhere in-between. I needed it to not be of any rigid material and decided to use rope, which has a tensile strength, but is fluid and supple.

While still looking at war in the Middle East, I made that structure loosely based on the façade of the Oklahoma City Federal building that was bombed by right-wing white supremacists when I was younger. This was the first time I was aware of that type of violence, and it was a homegrown terrorist, a white Christian guy with a vision. He blew up this building with all sorts of people in it, including children. When I started seeing the images coming out of Syria, they looked just the same, just the framing of these buildings. Once one is blown up, it looks very much like it does when it’s first being built. You just have that frame.

I began making work with the idea of representing conflicting ideas at the same time: that an ending is a beginning, that things get torn down, and things get built, that the structure can be both falling and rising. Sometimes the one has to happen for the other to happen.

Astri Swendsrud: One of the most active parts of my practice over the last several years has been a collaborative project with my husband and fellow artist, Quinn Gomez-Heitzeberg. This is a project we’ve been developing since 2012 called Semi Tropic Spiritualists—it began after we discovered that there was an actual utopian group of the same name that was established in Los Angeles in 1905.

At the time, they were established outside the city limits of L.A. Now, it’s kind of smack in the middle of Echo Park, and I had unknowingly been living across the street from the last remaining open bit of property that had once been the site of this communal group. I ended up finding out about it because my husband was, for reasons we cannot recall, reading some real estate blog and discovered this mention of the Semi Tropic Spiritualists’ tract, which had just been sold and was going to be developed for the first time in the city’s history.

And in the moment where this trace of a society that once had tried to exist on the city’s limit—trying to create its own structures for its communities and values and beliefs—was disappearing as an open place of potential, we decided to take their name and become the Semi Tropic Spiritualists. Over the course of this project since, we’ve been through a series of performative works and installations and other forms of interactive site-based projects that enact, or re-enact, these moments that seem to be part of the rise and fall of these attempts at forming a better society.

Semi-Tropic Spiritualists Test Site No. 1, 2012, detail of installation, photo courtesy of artist

(Indicating projection behind panelists) In these images, you can see some of the iconography we’ve developed, some of the furniture and artifacts we’ve made that become visual identities and ways of communicating the beliefs and values we’re creating for the Semi Tropic Spiritualists.

We’ve done a bunch of historical research, and found, I believe, almost every mention of the Semi Tropic Spiritualists that were part of early Los Angeles news reports. But there’s very little information about them that still exists today. We’ve never been able to tap into more than just a few isolated mentions of the formation of this group and the purchase of this property. They were running it as this sort of campsite-based community where nobody would own major portions of land—instead they would divide it into small parcels that were much more flexible and communally oriented in their habitation.

Looking into this void of actual restorable details, at first we were a little bummed that there wasn’t more information out there about them, but after a while it became an opportunity for our practice where we could step in and start going through the processes of forming a new belief system and a new society. We created symbolic systems and here you can see one of the banners that we created. We’re really interested in how communities create value or meaning and then communicate that through the material culture of trying to put intangible abstract values into concrete, physical objects and spaces.

Our whole project has become about this dichotomy spoken of already, this tension between the desire to manifest an ideal, and the moment that whenever that ideal is put into concrete physical form, placed into human social structures, the perfect sense of potential is going to be compromised. So, over the course of the last several years building this body of work, we’ve been playing out the arc that often happens in these utopian communities, from their very idealistic beginning points to when they become much more corrupted.

Currently, we’ve been researching a lot of ’60s and ’70s self-help movements. Once again there’s a very utopian-minded idea, but then that’s often harnessed into production of products or services that you’re trying to sell or promote. We’re currently in the process of developing furniture that’s supposed to help guide your decision-making processes and help you live a better life—surrounding yourself with furniture that can answer your most basic needs and deepest questions, which is, perhaps, a lot to ask for a piece of furniture. Join the attempt.

This image comes from a project we did in 2015 where we were actually able to work at a site that had once housed two utopians communities that both collapsed for different reasons. It’s called the Hatchery, located in the mountains between Sequoia and Yosemite.

We brought a bunch of L.A. artists up to create work and do a performance. Surprisingly, like fifty people showed up at this remote location for the event. In the show, we really tried to take on the history of the site through performative works that dealt with how easily that line can be crossed between positive ideals and that sense of maintaining control or power that so often impacts these projects.

Semi-Tropic Spiritualist Test Site No. 5, 2014, still from performance, photo credit: Anthony Bodlović and Ronald Dzerigian

It’s continued to be a really generative portion of our practice and a way to try and ask questions about why humans are constantly motivated to find new and better forms of living—as you say, Cathy, both the best and worst impulses are getting played out in microcosms of utopian social structures. There’s a lot more I could say about it, but I’ll just leave it right there.

Jemima Wyman: I’m going to give a super brief personal bio. I’m a mother of a three-year-old, and I was raised by a single parent, by my mom. She raised three of us for the majority of our lives, and I grew up in Australia in some very remote places, wandering in the bushes with kangaroos and climbing trees. Our local hangout at one point was a tree—we’d say, “I’ll meet you up the tree.” So, I do have some free-range, feral, radical feminist beginnings in certain ways.

And then a very brief summary of my practice: I’ve worked with “visual resistance,” generally looking at the ideological properties of textiles, looking at the history of camouflage and how masking and patterned fabric have been used in different instances for protection for groups that need to assert their counter-power in situations of conflict.

In the beginning, it manifested in terms of a feminist investigation where I used my own body and invented different characters that dragged femininity. And then I started to wonder where people in the real world were using masks and patterned fabric to protect themselves and to have some sort of liberation, or collective power.

Title: Free Pussy Riot Crazy Quilt, 2012; hand-cut photographs sewn on second-hand tie-dye t-shirts, 74 x 74 inches

This led me to study liberation armies, the Zapatistas in particular, how they had a nonviolent approach and an equal number of women in the movement. In my research, I then started to think about real and faux liberation armies and working with that in relation to social camouflage.

The project got to a point, I guess, where I felt conflicted about working with this, especially with the rise of ISIS and Hamas. I didn’t want to be generating more images of fear. Around the same time the Occupy movement started to get momentum and I noticed that masking was being used: this Guy Fawkes mask, specifically as the public face of the online hacktivist group, Anonymous. They started using the mask in 2008 to protest Scientology, but it then became the chosen face of protest across the globe appearing in the Arab Spring, Free Pussy Riot protests and even in Polish parliament.

In my practice research I began to ask, “Where is this mask being used, and for what protests?” I started to horde images from online, and started making collages, and it just kept growing along with the global protest movement. The Free Pussy Riot movement was using the balaclava for anonymity and collective power, but instead of being black like the Zapatistas, it was fluorescent and colorful, and they were wearing colorful dresses and inviting people to join the movement and have power in this expansive, collective, thronging ‘face’ across the globe.

Title: Visual Resistance, 2012; hand-cut collage, 79 x 59 inches

I guess my interest in visual resistance shifted from a personal feminist position of using my own performative body—I mean, it’s always kind of feminist—to liberation armies, to global protest movements. More recently, my work is generated from this archive that I’ve accrued from pulling all of these online images for the past eleven years, what I call the MAS-archive. It’s where I pull from to make textile works, sculptures, paintings, collages, performances art, as well as some social practice events. And sometimes I make collective protective architecture in the desert that people can work in and under—kind of like a giant dream catcher—utopian structures, or architectural results of imagining other potentialities. That’s where I see my work fitting in to the conversation: imagining collective spaces, archiving self-identified groups and mapping social imaginary imagery of collectives.

CA: In my practice, the archive is super important because I mine the records of these 1960s communes for images and stories. It’s been a really interesting process, because when you’re going into an archive, you bring your own meaning to it, of course. You reposition it in certain ways from your perspective, and it’s uniquely your view of these archives.

I’m curious if any of you can speak to your own experiences of researching archives and going back through the historical record and using that in your practice in new and perhaps different ways than they were originally intended for. Astri?

AS: I already started to mention that the Semi Tropic Spiritualist project came directly out of finding out about this historical group, attempting to gain more information about them, and ultimately not discovering any deep archive.

However, our research very much expanded to similar groups, such as the spiritualist movement that began in the early to mid-1800s on the East Coast in New York. By the time of the Semi Tropic Spiritualists in 1905, most of the practitioners who were taking that movement seriously had moved elsewhere, either to England, or many to California.

So, we started to research this very particular system of belief that had both religious and political aspects to its origin. We were interested in the way that this movement was so very popular at a particular time in history, and today . . . well, it still exists, but it’s much less common.

It was once again this split between the best and worst impulses in the formation of a new way of being. We did a lot of research into the way that early spiritualism was connected to both the feminist and abolitionist movements. It was an attempt to get outside of dogmatic spiritual traditions directed by a small group of decision makers and really democratize and open up the process of potentially accessing greater knowledge, or accessing something beyond the everyday structures of belief or practice.

It was fascinating to research early spiritualist mediums, who very often were women. It served as a way for women to activate their voices in society, in contexts where they normally would not have been allowed to make public address. They found this perfect loophole in being able to say, “I’m channeling spirits. You have to listen to me.” And it just so happens that the spirits were really invested in equal rights for women and the abolition of slavery, and it was this great workaround.

Whereas, on the flip side, there was also this highly spectacularized and manipulative form of spiritualism that was all about manifesting these tricks of producing ectoplasm, or making things float—becoming this sideshow practice that was meant to manipulate people and get their money.

Back to the notion of archives: we started to follow both trajectories, from the spiritualism that came out west and started to establish these spaces in the early 1900s—trying to model new ways of living and being—to their tendency to really split down the middle between this highly idealistic community or a highly controlled and controlling and manipulative community. This led us into researching all of these sites and instances around California where we have often been able to do projects. We did a project at the site of Llana Del Rio in the desert, which was a much more socialist utopian society that briefly had its time. A lot of our research has driven the physical manifestations of our projects and built upon them.

CA: As I was listening to you, and thinking about what Micol said earlier about the 1960s and 1970s all of a sudden being hip and cool, it struck me that one of the reasons why I wanted to get deep into these archives Morningstar and Wheeler’s Ranch is because it was freely available online—everything was right there if you wanted to find it. But it was so unconvincing in a way, this surface image of “we’re all chilling out and look how cool we are, all dirty, hanging out by the campfire.”

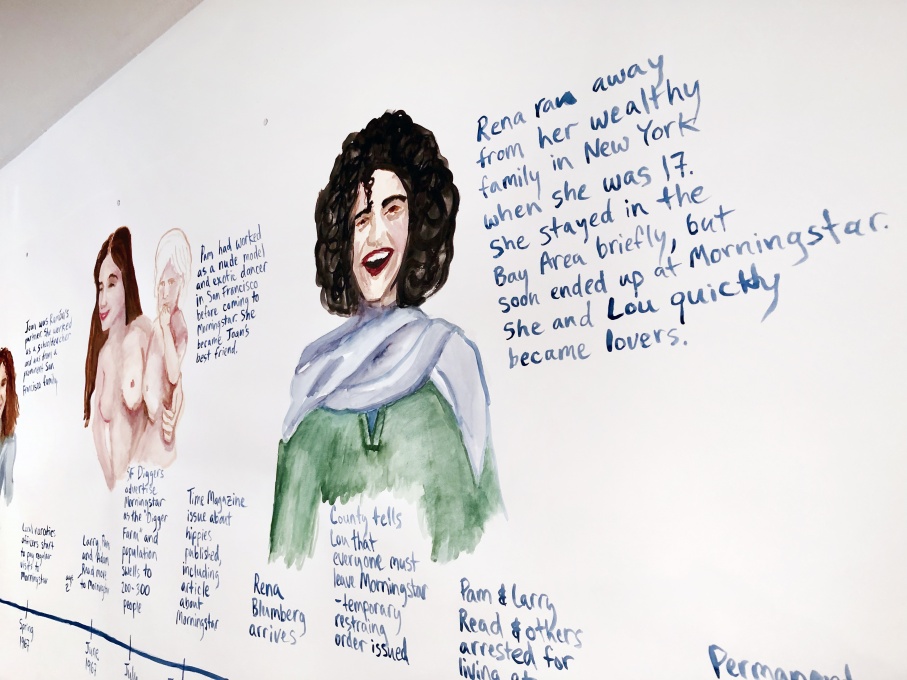

Timeline detail, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheelers Ranches Reconsidered, Lenzner Family Gallery at Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, February 2 – March 28, 2019

It’s a very seductive image, where everybody is supposedly free and life is easy. Because there’s a sort of fetishization that happens based upon the imagery, I thought, “That can’t be the truth. I want to find out what actually happened.” When I went deeper into the stories—not just the things that are easy to find, but the stories I heard from people when I met them—the reality was anything but carefree. That was just an image.

Coming out of my training as a photographer, I’m interested in what is behind the image, what is the reality that they’re depicting. They’re not accurate portrayals of truth, so I wanted to see what I could find through, literally, ten years of going further and further and further into these stories of people’s lived experiences in these places.

That was a really interesting process for me, and I enjoyed the excuse to get to know a place and a group of people that I wouldn’t normally.

JW: Just to add, the book in Cathy’s exhibition is amazing in terms of the way it highlights the really idiosyncratic experiences on those communes. It’s actually devastating to read some of the personal accounts, the way they reveal all of these unspoken things that a lot of women were experiencing. That’s often covered up—the aura of the commune is this utopian experience, so then to hear these really dystopic experiences is even more disturbing and upsetting.

Audience member: And what about the use of archives? [To the panel] Do you see them as part of your work?

CP: I approach archives with the same skepticism as I would bring to a family photo album. I can imagine a big family getting together on a holiday and going through the album, and each person has an absolutely vivid memory about a place in a photograph—a trip, or whatever—and they don’t match up.

We know this about memory now. I have a deep distrust of recorded history.

CA: That’s why I love archives, though—they’re so slippery.

AS: We’re constantly rewriting not only our source material, but what we are producing as well, very intentionally.

JW: Cathy, you’re looking at the archives that go around these two communes but also generating information that goes into those archives—it’s a really dynamic gesture.

CA: For me, archives are dynamic. Photographs are seen differently by different people. Stories are read differently by different people. It’s this ongoing renegotiation of the past, in present time. I like the way that it expands and collapses on itself: it’s this ever-changing thing that’s not necessarily in the past. That sort of slippery nature of time is encapsulated by an archive, or can be. I like that about it.

JW: One of my favorite quoted definitions of an archive is that it’s the secretions of an organism—but that still doesn’t erase the distrust.

Audience member: It seems like everyone is focused on the archive in terms of written work or photographic evidence: to me, the most important and longest-lasting historical archive we have is actually ceramics. And as an object-maker, I think of the archive as encapsulating more than what you’ve described—and, you’re all also working in that way, creating objects that are part of these histories. I’d be interested in hearing everyone talk about how objects fit in.

Installation view 2, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheelers Ranches Reconsidered, Lenzner Family Gallery at Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, February 2 – March 28, 2019

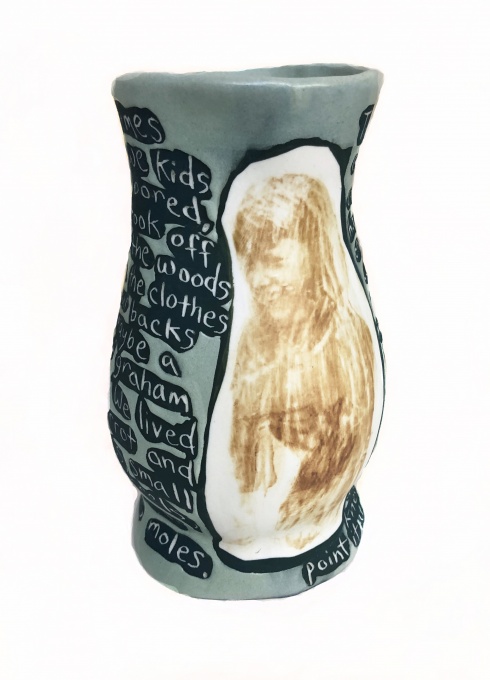

CA: Well, I feel the objects that I make are calling upon the history of vessels as storytelling devices. I was drawn to the form of the vase and ceramic art as a medium precisely because the Greeks and Romans and many other cultures used them to inscribe stories and pictures and have them be this repository of cultural knowledge.

The reason I personally mine the photographs and writings from this particular period is because there are not a whole lot of objects that remain, as Micol pointed out. The real residue is the written word and the photographs.

CP: But you’ve had personal interviews and whatnot also, didn’t you?

CA: Oh yes. I’ve been to all these places and talked to all these people. I think the multilayered potential for meaning within photographs and the written word is interesting, as opposed to starting from the objects. I start from those things and I make objects from them. That’s in my practice. I’m always looking at narrative, and the building of narrative, to show what’s important in a culture or in a society.

Audience member: I was in a history class and we were talking about primary sources and secondary sources, and my professor said, “A primary source about something that happened in 1910 would be someone writing in 1910, and someone writing in 1970 about that same event is a secondary source.”

But it could be a primary source about how people in 1970 write about things that happen in 1910, and that’s how I feel about the slipperiness of archives: if you pull out a picture and everyone remembers a completely different thing, it doesn’t necessarily mean you have to distrust it. It means that you learned in that secondary way—you still got information, archival information, but everyone has a different opinion and a different memory. And you still learn the fact of that.

If it’s a specific thing, you might reveal a gender bias or race bias in how people remember things. What are your opinions on the archive not as something you can read truthfully, but as something untruthful you can still learn from?

JW: I feel like I use the untruthfulness of images online and the masking and anonymity as permission to engage with these images, making my own liberation armies or thinking through what these images stand for in terms of a social imaginary space. I am often creating groups that never existed together before, by looking at individual choice of ‘social camouflage.’ By analyzing protesters choices of masking and clothing, I feel like I can learn a visual language that is being used for practical consequences. The ‘untruthfulness’ of the masked images I collect puts an onus on the viewer to be sensitive to their psychological interpretation of the figure presented whether that is utopian or dystopian. The ‘anonymity’ of the image can raise different desires and I guess that is the lesson.

CP: [Addressing CA] How many of these children you’ve talked to as adults romanticize the past and try to bring those values into their current life? Or do they end up running Silicon Valley? What happens to kids who are raised in that kind of freedom?

CA: The kids don’t want to talk to me, universally. It was their parents’ trip, not theirs.

JW: That comes up in the text in your book, too: there’s one quote in there where all the kids are invited to a birth, and the kids are like, “Hell no. I don’t want to see a baby being born. That’s crazy. You guys are crazy.” That was so interesting, where it was really clear that the kids differentiated between what the adults were doing and what they wanted to do.

Cathy Akers, Wild Child, 7.5”H x 4”D x 4”L, 2019; porcelain, photocopy transfer, underglaze, and glaze.

The text reads, “Sometimes, when we kids were bored, we took off into the woods with the clothes on our backs and maybe a pack of graham crackers. We lived on wild carrots and watercress, small birds, squirrels and sometimes moles. They were easy to catch if we hadn’t taken one of the .22s with us.”

CA: I was actually at some of these people’s houses and the kids were there, and they just refused to talk to me. The parents identify strongly with this time period, and there was really the sense—especially among these two communes that I researched—that they were going to change the world. It was the dawning of a new age, and nothing was going to be the same after this.

One reason why their archives are so extensive is that they still believe it might be possible. If more people visited the archives and saw the way they lived, saw the fact that they didn’t believe in private property and land ownership, the problems of the world could be solved. They’re still on the bandwagon.

AS: That relationship between kids who grew up in these situations looking back from their own perspectives, versus that of the people who built those situations, is really fascinating because there’s part of that collective communal impulse that is weirdly also very individual, since it’s based on this personal choice to opt out of societal norms.

It’s one thing to choose that for yourself, but to be a kid growing up within the context of, “Look, you’ve opted out of societal norms”—that’s placed on the child, rather than a choice made by them. I know that Jemima talked about growing up free-form, but I grew up almost the exact opposite, which was in a very strict, religiously oriented group that took on cult-like tendencies, if not being an actual cult. And yet my parents, similarly, had a vision that this was the right way to be, something they were excited about—they were building the tools and trainings to make a better world. But for myself and the rest of my peers, it immediately felt constraining and the opposite of liberating or any exciting way of moving forward.

So, there’s that split between one generation’s opting out of society, and seeing it as a vision for progress, and those who were raised with it, without the choice to reject any values.

CA: Maybe that’s always the dynamic of why we do things. In the process of this research I discovered that the reason my mom never cared about the hippie movement at all was because she grew up in abject poverty in the South, and all she wanted was a house in the suburbs and to have material comfort. For her, these people were crazy. Maybe that’s why I got interested: it was something she wasn’t interested in.

JW: Thinking about your personal biography, or experience growing up, and that you’re reenacting it making contemporary art, that made me wonder: Is contemporary art a safe space to test out these ideological experiments in some ways?

AS: For many years, I really separated my biography from my practice, at least consciously, but then realized that probably wasn’t what was actually happening. So, it was a re-approach, using it as a testing ground, or a way to try to get at what is behind this mentality, asking why does this desire occur to create a new system for living and building from the ground up?

By bringing these conversations to the surface, which seems like something that has been increasingly present in contemporary art in the last ten years or so, there’s a lot of us trying to reconcile and deal with these complicated personal pasts and histories.

CA: Let’s talk a little bit about the actual materiality of everything that we all make. For myself, I started out dealing very much in the two-dimensional plane with photography. As we’ve been talking about archives, I recall that starting to work with clay was a way for me to have a different relationship with my body and I found that working with this tactile, physical thing was a really intuitive, lovely, freeing process, where I didn’t have any expectations about what I was going to make. It seemed like a great way to have this embodied relationship to the text and the images I was using. I’d never seen myself as a three-dimensional person of any sort before that—it was really exciting.

Claudia Parducci, Production Line (Red), 2018; Wood Burro sawhorses, jute, Procion, MX dye, 40 x 120 x 42 inches

CP: I feel very constricted by even identifying as a sculptor or a painter. For me, I learn new skills any time I have a project, usually requiring me to learn how to build, how to cast, how to sew, or in this case, how to knit, how to knot, and how to dye.

Part of the pleasure in art-making is starting over, always starting over. I like to be at square one. I didn’t even know when I started this project that it would turn into two years of knitting, and I didn’t think a lot about the meaning of knitting and the craft and whatnot. It was an idea, something developed over time.

Audience member: Can you address how craft fits into your practice?

CP: I would like to abolish the term “craft” as it is commonly understood. When I think of the maker generation, I just feel that we’ve outrun the traditional meaning of the word. There have been many traditional meanings, but overall that mindset has dissolved in the art world, or I would like to believe it has. I feel as if we’re trying to attach a new fixed meaning onto something that we’ve broken away from already. I don’t want to be boxed in all over again.

I applied for a grant last year, for a fiber art thing. I thought, “Well hell, why not? Maybe I’d fit for this.” If fiber is part of your art, you, too, can apply—but all of the questions were about showing how what you do relates to the tradition of this kind of making. So, to me, that’s still this connotation of craft, something coming out of and committed to a tradition. We can’t ignore that history, but do we have to confined by it?

AS: They all have traditions and history.

Audience member: I consider craft, actually, as a marker for just women. We’re knitting and that becomes craft, and then we make pottery and that becomes a craft—cooking becomes a craft, but if you are a man cooking, then you’re a chef. If you look at Native American culture, the weavings and paintings and pottery that they made are often described as craft, but they’re clearly art.

Often we get confused by craft because it’s a noun and a verb: instead we should think of it as a disposition, and that as such, it has all of these things to offer us that art, for one, doesn’t. Or could have. One example would be the embodied experience of working with the material and having it transform you as you transform it—that’s powerfully missing in our culture, in our world.

Another thing is this exchange economy, that for millennia crafts have relied upon exchange rather than a capitalist system. There’s also a flexibility of process, and lots of little ways in which craft could be emboldened to be more potent and more powerful in working towards solving some of our world’s problems.

When you say “let’s get rid of craft,” or “let’s ignore it and embrace this other thing,” it worries me that we lose sight of all the positive things that craft can do that can affect critical social change.

Installation view 2, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheelers Ranches Reconsidered, Lenzner Family Gallery at Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, February 2 – March 28, 2019

CP: I’m talking about syntax, really—”craft” as a term.

JW: As opposed to “art,” or something else.

Second Audience member: The word comes from an early English word that means “make.”

Tim: I think it gets trickier the further back we go, or the more expansive our view. Right, we’re using an English term in a well-defined Western history to talk about these things that have had real purpose in the world for all of humankind. I’m just trying to figure out what our place is in that history, and how we start to think about the potentialities of these materials, processes, techniques, skills—things you’ve all touched upon—but really activating them socially to make a more just world, a utopian agenda for craft to embrace.

Much of the conversation has been these two threads that haven’t really come together, craft and these utopian agendas. There’s such an interesting parallel history that goes back over 150 years through the Arts and Crafts movements that sought to remedy some of these exceptions . . . though I don’t know what that similarly would be called in our world.

Audience member: Can you clarify how you’re thinking of utopia? Is it a just and a free world?

CA: It’s defined differently by different people, but a lot of 1960s communes thought of it as a world where you have individual freedoms and can do whatever you want, basically, but you’re part of a supportive system. That’s what they were going for. They don’t believe they got close to achieving it in most cases, but that was the idea—also, a non-capitalist, money-free system, a free exchange of ideas where nobody had more power than anybody else. An equitable situation.

CP: Part of the problem in the concept of a utopia is the idea of making a system that would work for everybody. I would imagine there are people for whom utopia would be where everybody worships the same god in the same way, lives by the same rules. That would be somebody’s utopia—it would be somebody else’s dystopia.

CA: There’s also the idea that Astri brought up of these very regimented societies where everything is decided for you ahead of time as a kind of utopia, because you don’t have to have doubt and you don’t have to have fear.

AS: It’s also a very particular kind of mind that wants that sort of system. If I don’t have to doubt something, I feel safe, versus somebody else who might say it’s doubt and curiosity and investigation that make me feel fulfilled.

CP: I do think it’s a utopian impulse to try to build a just society.

AS: That’s why I like the title of your show, A Utopia for Some, because that brings up the idea of this scalability of utopia, and the relativity of it.

CA: It’s always the problem with utopia.

One of my initial impulses in being attracted to these communes was their profound optimism that things could be changed and that they could and would be the ones to do it. It’s an overly inflated opinion of what one can do, but it does have this agency. We now live in a world where we understand, or maybe better understand, how things work. Back then, I think they decided that they didn’t want to understand, or had a very simplistic version of how things worked, and that through their effort and desire they could change that. It’s both wonderful and completely stupid.

Audience member: I’m hearing a lot of judgements about people who choose or chose to live that way, about how they were ignorant of certain types or ways of living—they were optimistic, but now, how could they be? The dialogue is very closed, and I’m saying this as an artist and educator, and someone who worked in a commune for twenty years—I raised a child in a commune, who is now a professor. The optimism of feeling like you can choose your world is still part of many of those people’s lives, and in many cases they did that through their children. Those children are now enacting those beliefs and working towards those same changes.

CA: I’m speaking from my experience talking to these people that I’ve met, and talking to many who founded or were on communes as young people.

Audience: I was the founder of a commune.

CA: I’m not saying your experience is invalid, just that from the people I’ve talked to, I’ve heard that the culture at that time in the mid-1960s was very different than our multifaceted, diverse culture today. They perceived it as being that you’re either part of the mainstream, or you leave it. There was no third space, fourth space, fifth space where you—

Audience member: There were lots of different types of communes. There were farming communes, spiritual communes, communes in the middle of cities.

CA: Yes, but I’m talking about two. I’m not talking about communes in general.

Audience member: I’m just hearing generalizations.

CA: From what I’ve heard people say, there were fewer choices. Some who I talked to said that if it was them today in the present, they wouldn’t join the commune because there are now so many choices in mainstream society—back then they felt that there weren’t. And for my parents, also, the 1960s was a cultural moment, a time when people were really trying to reinvent the way they lived. They chose a suburb that was an intentional community, in many ways, because it was designed to be racially integrated and was also supposed to be a garden city, with lots of shared, natural spaces.

The emphasis in delving into these communes comes from being raised with a sense of that same energy, because my parents were among the first people to live in this community. There was this energy around starting something new, a new world, a new beginning, a new possibility for how you can be together.

That sense was widespread through many segments of American society at that time, and that rising up of a desire for change is an amazing thing for a society to experience as a whole. I feel like there are aspects of that in where we are right now, and it’s an interesting moment to be in, this moment of potential for cultural change.

AS: And that sense of continued relevance comes out in how thoroughly you’ve immersed yourself in this. But it does raise the question: There’s a really positive aspect to experimenting with a new model of living, but if it’s only kept within the confines of a small group, what does that actually do for the broader society?

Maybe the short-term nature of many of these groups, of people cycling between positions, could very much be seen as a positive because the ideas are spread abroad. And even what was mentioned about the children growing up in these situations going out and rejoining society, but coming in with a different mindset and mentality . . . there needs to be that sense of flow, not that you are escaping from the world, but that you can bring things back and think about large or systemic changes, or add complexity to our ways of living.

Timeline detail, A Utopia for Some: Morningstar and Wheelers Ranches Reconsidered, Lenzner Family Gallery at Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, February 2 – March 28, 2019