Cry Tough: Glam Metal on the Sunset Strip

by Nick Stillman

Cover art for Poison’s 1986 album “Look What the Cat Dragged In.” Photo: Scarpati.

It’s 1992. A lead singer with a blond mane breezes into a glassy building and strides toward the elevator, clicking his teeth in time to a beat. He’s a tall, clean-shaven guy with tattoos and broad shoulders. His chiseled facial features are flourished with makeup, but he’s not in disguise. Just the opposite. He crosses the lobby clamorously, necklaces and earrings clanging, leather clapping against leather. The echoes of his stiletto-heeled boot steps announce his presence. Unconsciously, he reaches a gloved hand to his crotch. Yes, his leather pants are cinched tight. Two of his band’s singles have charted as high as number 2. Their last album reached number 7 on the Billboard 200 in 1990, and its initial single is a testament to his heterosexuality, so he couldn’t give a fuck what people are whispering about his leather pants and eyeliner. The band has already recorded a follow-up album, which will be their third. He’s riding a beer buzz. He has no idea that he’s living his last minute on top of the world.

When the elevator doors swung open on the foyer of the Columbia Records office, there sparkled Jani Lane’s grim new reality: the nineties. In the arena of rock and roll, the nineties started a year late—in 1991, aka “the year that punk broke.”1Hair metal retained its radio and MTV presence into 1991, with second-wave bands like Slaughter and Lane’s band, Warrant, vying for position with originals like Mötley Crüe, Poison and Ratt, but its cocky wail had been blindsided by a distortion-soaked grunge mumble. By 1992, the hair metal publicity machines and fan base were switching sides. Back in the Columbia office, Warrant’s Cherry Pie poster had been taken down; up went one for Alice in Chains’ Dirt; Lane understood the symbolism immediately.2A few years later, the band couldn’t really be blamed for their pathetically transparent image transformation. Never before had the record industry dropped a moneymaking genre of music as sweepingly as it had theirs.

The hair metal story begins around 1982 in Los Angeles.3Hardcore had become the new locus of the city’s rock scene, but clubs were loath to book bands like Black Flag and the Circle Jerks for fear of the violence promulgated by adolescent suburban brats and spectacularized by the media.4Hair metal swaggered into the void. Like the Byrds, the Doors, Love, X, and the Germs before them, the eighties hair metal bands were a product of the Sunset Strip rock clubs.5Plenty of American music from the mid- and late eighties sounds good today but, plainly, hair metal doesn’t—it has aged gracelessly. Its vapid anthems and cloying ballads seem wimpy compared with the hardcore (even the hard rock) that preceded it, and inconsequential against the grunge that swept it into the dustbin of irony. When Félix Guattari wrote that “every semiotization in rupture implies a sexualization in rupture,” he may as well have been describing the grunge coup.6If the semiotic rupture in question was grunge’s heavier guitar sound and more intelligent lyrics, the sexual one was embedded in the fashion.

The evolution of Warrant’s look from the 1980s (top) to the present.

The grunge look for either gender was a blue-collar uniform of flannel and denim. Like the music, it was accessible and attainable. The hair metal look was just the opposite; it was an explosion of excess. Its emphasis was exaggeration: bigger, higher, tighter, more. This isn’t inconsistent with eighties fashion in general, and the spirit of largesse jibes with domestic political rhetoric of the period that pitted the US as the capitalist, “free” counterpoint to the communist, spartan, and (thanks to soft propaganda like Rocky IV) robotically homogeneous people of the Soviet Union. Outrageous image was the defining commodity of the decade, and eighties flamboyance is an enduring source of camp entertainment. But eighties America was conservative, especially when measured against the social upheaval of the previous two decades. Much of the country’s (often clandestine) involvement in foreign conflicts promoted industry privatization in developing nations, leading to their plunder by the heavily right-wing American business elite.7The rich got richer—assuming they were able to stay out of a savings and loan scandal.8Culturally, the spread of AIDS exacerbated homophobia, and concerned-citizens groups joined with legislators to persecute artists, musicians, and writers whose work disrupted their quaint fantasy of American normalcy. All told, the eighties were closer in spirit to the McCarthyist fifties than to the sixties or seventies, especially for artists. This was the conservative context that spawned hair metal, and while a prominent handful (justly) bemoaned the genre’s misogyny or protested its “overt expressions and descriptions of often violent sexual acts, drug taking, and flirtations with the occult,” nobody seemed willing to contend with the bizarre elephant in the room: these “often violent” deviants were wearing spandex bodysuits and lipstick.9Right in the middle of a period that was particularly suspicious of art that challenged the status quo, hair metal managed to be a popular mainstream cross-dressing movement without stirring up much of a controversy. How was this possible?

This question picks up on Mike Kelley’s 1999 essay “Cross Gender/Cross Genre,” in which the artist discusses the connotations of cross-dressing during “the psychedelic period” of the mid-sixties through the mid-seventies. Using hippie fashion, the Cockettes, Jack Smith, the Mothers of Invention, John Waters’s characters, Eleanor Antin’s early photos, and other period examples, Kelley links drag to the progressive culture of the era: “If America’s problems were the result of being militaristic and patriarchal, the antidote would be the embrace of the prototypically feminine.” According to Kelley, American white male youths growing up in the sixties discovered political consciousness via the threat of military conscription and the empowering spectacle of black civil rights protest, causing their “profound empathetic connection to ‘otherness’ in general.”10By the mid-seventies, glam rockers like David Bowie and Marc Bolan had normalized androgyny as a typical male rock-and-roll stage stance, and by the second half of the decade, female rockers like Patti Smith and Joan Jett were flipping the script on the baroque male glam look by adopting a leather-heavy punk look. Punk femininity looked an awful lot like masculinity. For a few years, the male-to-female gender confusion of rock and roll calmed down. So what were the conditions that enabled hair metal drag to appear during the eighties, and could its Los Angeles manifestation reasonably be connected to progressivism?

First, a look at exactly how drag reappeared in the hair metal era. If the psychedelic epoch represents the other recent pop-culture moment when men adopted women’s fashion norms, there’s one glaring difference between the ethics of hippies and metalheads: hippies dressed down, and metalheads dressed up. The hippie costume was easy to affect. The hair metal look was willfully difficult. It required constant shopping, shaping, and maintenance, and its spectacular mash-up of glam camp and leather tough was a winning promotional tool. Not since the high psychedelic era had a cadre of mainstream musicians put forth such a unified image front, and these images became relentlessly visible on album covers, in magazine pinups, on MTV.

The only vestige hair metal retained from the hippies was long hair, although often with bangs that were teased to form a stylized crest. Sweet Pain’s Corky Gunn describes his technique in Steven Blush’s book American Hair Metal: “You would turn your head upside down so your hair hung down and spray it like crazy, then mat it down and shape it a bit. You’d end up looking like a chick, but the girls really dug it.”11Metal bands were notorious for their aggressive distribution of promotional fliers along the Strip, and salons previously patronized almost exclusively by women had a new and supremely image-conscious client base on their hands. They responded with fliers of their own that advertised special band rates.12Lipstick, eyeliner, and mascara were standard. Blush, eye shadow, and fingernail polish, while less common, were acceptable. Accessories were crucial: hats, earrings, necklaces, rings, bracelets, headbands, pendants, dog tags, chains, scarves, sunglasses, gloves, feathers, animal teeth, anklets (stretched around the outside of a cowboy boot). These were often worn in multiples, especially jewelry and—inexplicably—belts. Black leather was always appropriate, but color was not taboo. Poison made lime green their trademark. Pink was popular for its feminizing qualities. Some rockers, like Stryper’s Robert Sweet, wore customized, full-body spandex jumpsuits emblazoned with band logos.

Christian glam metal band Stryper, ca. 1980s. Photo: Scarpati.

The hair metalheads weren’t the first apparently heterosexual rockers who cross-dressed. That distinction belongs to the New York Dolls, the crucial link between seventies and eighties glam, even if the metal bands’ experience of the Dolls was mostly filtered through the stage histrionics of Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler, who in Decline declares his admiration of the Dolls’ David Johansen and his “lips for miles.” The Dolls were a working-class protopunk band from New York that, since their inception, in 1971, dressed in an outrageous scuzz-glam style. By the time of their 1974 shows at Club 82 in New York, they were suited up in full drag—not only makeup, but dresses.16Despite the band members’ effete posturing, they were, by every account, straight.17 A thorough explanation of the Dolls’ motivations for cross-dressing has never really been offered, though the model Cyrinda Foxe (who became Johansen’s wife) speculates in Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk that Johansen introduced it because of his “wanting in with the whole Charles Ludlam gang,” whose Ridiculous Theatrical Company actors routinely appeared in drag.18Johansen claims that the Dolls dressed in drag for uncomplicated reasons—they assumed flamboyance was mandatory for rock stars. His explanation a few pages later is more convincing. Speaking of Club 82, a well-known drag club, Johansen says, “The audiences there were pretty depraved, so we had to be in there with them. We couldn’t come out in three-piece suits and entertain that bunch.”19Johansen implies that the Dolls’ decision to cross-dress was part empathy, part shtick, which is affirmed by photographer Roberta Bayley, who says, “I didn’t really get it, I didn’t know they were dressed in drag as a joke.”20

The New York Dolls, ca. 1970s.

When persona becomes role play, when everything appears in quotes, then an act is probably a camp act, according to the conditions outlined by Susan Sontag in her seminal “Notes on ‘Camp.’” The Dolls were performers of a weird set of tongue-in-cheek inversions whereby they “talked very gay” and were “playing gay” but were defiantly heterosexual. The Dolls were camp. In Vested Interests, Garber asserts that “any serious account” of cross-dressing must deal with its relationship to homosexuality. In the case of the Dolls, it seemed like that relationship was actually founded on empathy. They certainly weren’t taunting their gay audiences—they depended on them; the Dolls were a hit in New York’s gay bars and clubs. Whether the city’s gay scene of the seventies sculpted their look, or vice versa, is a chicken-and-egg question; but the Dolls had a significant investment in New York’s underground gay culture, regardless of their own sexuality, and if dressing in drag grounded that connection, all the better for the band. As it turned out, their drag stage act also functioned as an advertisement for their heterosexual virility, at least to the target audience of that virility. In Please Kill Me, Dolls drummer Jerry Nolan says, “Let me tell you something: it turns out women knew immediately. It was the men who were confused. The women knew, I don’t care what we wore.”21Prior to hair metal, the Dolls were the quintessential rupture to the assumption that transvestites—especially “performing transvestites”—were presumably gay. Ten years later, hair metal muddied the association between homosexuality and cross-dressing even more.

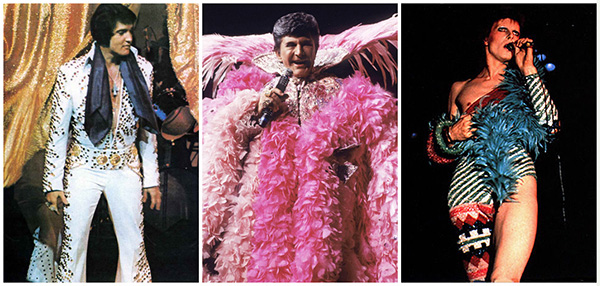

Hair metal’s insistence on its raging heterosexuality was its means of courting straight audiences of either gender, so for it to be outed as a closeted posse of queer queens would have been a PR disaster. Its participants constantly cite the attainment of (hetero)sexual fantasy as their primary inspiration for playing in a metal band and dressing in the metal style. “Notes on ‘Camp’” sketches a somewhat dated but still plausible explanation of the concept of camp—and hair metal is nothing if not camp. Sontag writes, “The androgyne is certainly one of the great images of camp sensibility … What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine.”22In fact, there’s a distinct lineage, from Elvis to Liberace to Bowie to the Dolls to hair metal, that points not just to a historical acceptance of androgyny in rock and roll but to its equation with masculine virility. Judging from photographs of metalhead groupies willing to play sexualized caricatures backstage and in videos, and women like the one in Decline who purrs, “It’s a turn-on for me to kiss a guy that’s got redder lipstick than I do,” there’s a lot of evidence that they found their fussy drag sexy. In Blush’s book there are candid photos of girls being groped and giving blow jobs to bands at hair metal shows. Mötley Crüe’s Tommy Lee recounts the disturbing memory of telling a backstage teenager that if she wanted to fuck the band, she had to wait for them naked while squatting on a bottle of champagne for an hour, which she willingly did.23Paul Stanley of Kiss—a band that, like Aerosmith, survived the transition from glam rock to hair metal—is shot from above during his interview in Decline while lying in bed with a gaggle of silent, admiring women who softly stroke his leather. Maybe as subconscious reassurance—to both the subject of the camera’s gaze and to the admirers reaching for their wallets—hair metal pinups are infamous for the crotch shot.

A brief history of androgyny in rock. Left to right: Elvis Presley, Liberace, David Bowie.

So, Sunset Strip testosterone in the eighties wore women’s clothes. “It has that sizzle!” raved twinkle-eyed, grandfatherly club owner Bill Gazzarri in Decline.24The conventional justifications for drag—escaping repression, getting a job restricted to one gender—don’t seem to apply to hair metal. By all accounts, these were alpha-male high school bullies who were strutting around like oversize peacocks. Was the hair metal hero an “unconscious transvestite”? Garber’s qualifications for unconscious transvestism are that its participants don’t consider themselves transvestites (check), and that their wardrobe is paramount to their success, stardom, and how they’re received in the media (double check). Hair metal fashion gratified the enduring demand of pop culture: escape through spectacle. The style could even be considered an extreme technique of differentiation from their audience, haloing them with the godly aura of unattainability, as their obscure commodities and styles were endlessly refashioned in publicity images and on MTV.