Dance of the Wild Men: Felix Art Fair 2021

by Claudia Ross

Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, Los Angeles, circa 1960s. Source unknown.

At the circus sideshows of the 19th century, ringmasters used four key practices to frame their performers as “freaks.”1The first was the “oral spiel,” a short speech delivered to a crowd of onlookers that certified, falsely, a given performer’s “monstrous” qualities. The second was a textual account, usually in the form of flyers or pamphlets, detailing the human exhibition in hyperbolic, eye-catching language that erased “the accurate story of the life and conditions of those being exhibited.”2The third was especially important: staging. Acts were put on elevated platforms that set them apart from the audience, denoting sideshow performers as objects viewed for entertainment. The fourth and final element of sideshow marketing was visual ephemera, the distribution of which (either bought by patrons or given out for free) disseminated images of so-called “freaks” beyond the ring of the circus. These photographs and drawings, often mounted and framed, were intended for display in “the Victorian parlor or family album.”3From sensationalist language to museum-ready wall mounts, each practice employed a combination of rhetorical strategies to encourage the sustained monetary value of the show.

Barnum & Bailey Poster (1899), presenting from left to right: an East Indian Dwarf, Tattooed People, The Bearded Lady, What is She?, The Human Terrier, Moss-Faired Girl, The Sword Swallower, The Double-Bodied Wonder, The Living-Skeleton, The Egyptian Giant.

Okay: sales assistants, press releases, pedestals and frames, visual art. The leap between circuses and contemporary art fairs like Felix’s 2021 presentation at the Hollywood Roosevelt is not such a wild one. In 1841, P.T. Barnum founded his famed American Museum on the former site of Scudder’s Natural History Museum, acquiring Scudder’s collection in the process. Barnum applied the frameworks of art galleries and museums to his displays of human oddities—and later, his traveling sideshow performances—when introducing them to the American public. Showmen like Barnum often “referred to freak show lecturers as ‘professor’ and ‘doctor,’” and placed the word “museum” in their exhibition titles, referencing academic, governmental, or institutional credentials to legitimize their exhibitions.4For the four days that Felix Art Fair was installed at the Hollywood Roosevelt, poolside and garden cabanas were repurposed into galleries that magnified the attraction of the work on view. White pedestals replaced tables, beds, and chairs in the hotel rooms. Maps were handed out to wristbanded guests at the Roosevelt’s Gothic entryway, showing attendees how to navigate the transformed space. Gallerists greeted collectors knowingly, preaching to the passersby that the fair—and their show—was worthy of time and money.

Every circus needs a ringmaster: Felix entered the Los Angeles art scene in 2018, led by gallerists Al and Mills Morán and former Disney exec Dean Valentine.5Branding itself as the anti-Frieze Frieze, Felix is an exclusively L.A. art fair—all 29 galleries included in its 2021 exhibition are either based in L.A. or have outposts in the city. Felix welcomes its Hollywood affiliation with tongue-in-cheek marketing, the most elaborate of which is their website, an “infinite scroll” screenplay written in second person, wherein the fair attendee (“You”) marches through the fair’s offerings, weaving in and out of conversations between celebrity guests and eating at Uncle Paulie’s. Emulating its script, the fair itself unfolded as a site-specific theatre in which guests, gallerists, and artists promenaded between the works on view. The ensuing performance was equal parts decadent and mannered, aware of its own elaborate display. Cocktails went for $15 and Felix-themed beach balls filled the Roosevelt’s Hockney lagoon.6A small camera crew tailed Jerry Saltz. Eric Andre and Hunter Biden were in attendance. And the party! The pool! The margaritas! If glamour—and all its painful self-consciousness—were a genre, this would be it.

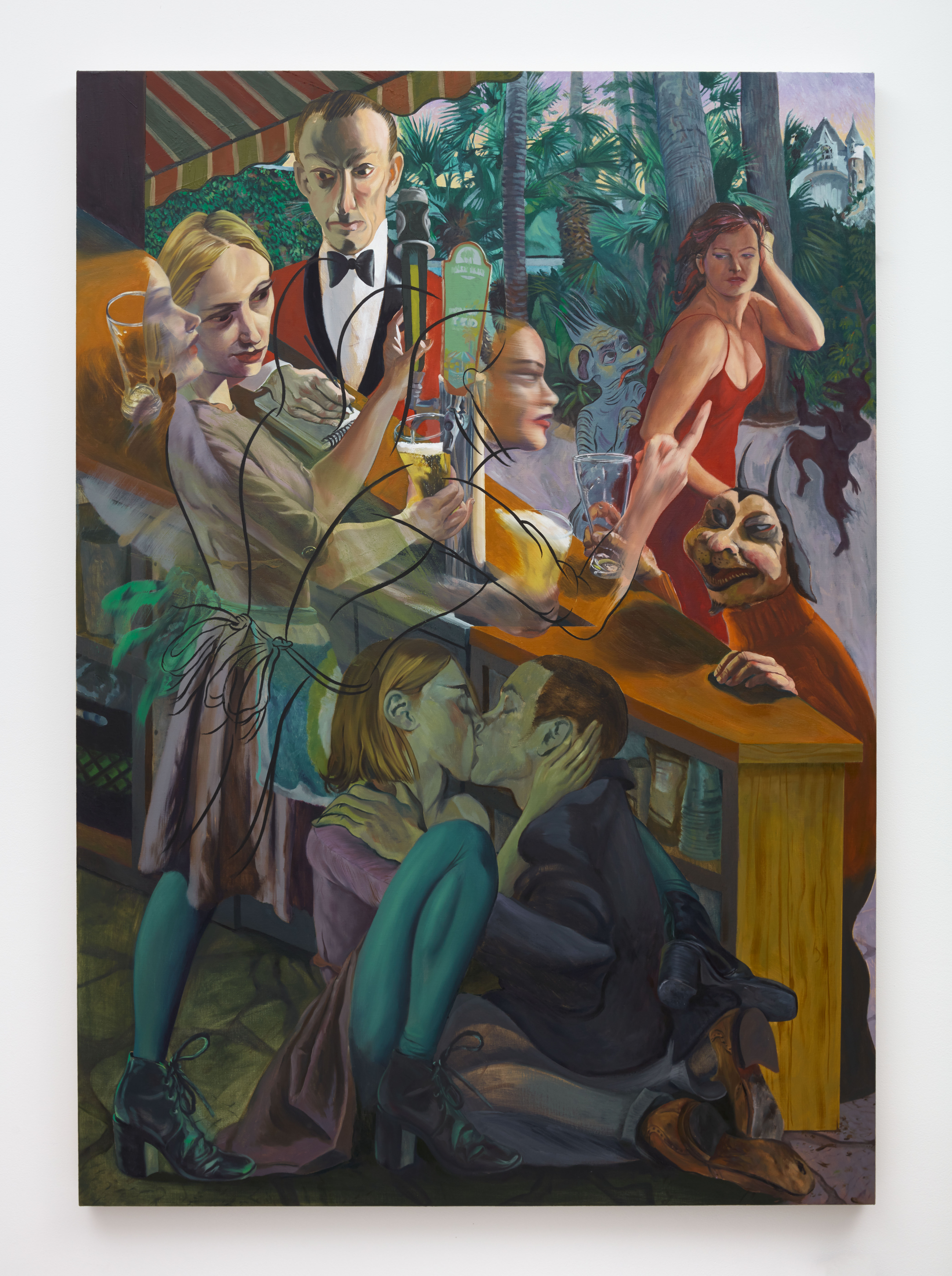

Justin John Greene, Frieda, 2021, oil on linen, 54 x 38 inches (137.2 x 96.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles.

The artwork on view at Felix further emphasized the performative nature of the fair, often using stock characters or mythic creatures within their respective media. Justin John Greene’s Frieda (2021), shown at Bel Ami, imagines an unmistakably contemporary scene—palm fronds and a red and green awning fill the background, eerily reminiscent of the Roosevelt’s lush gardens. A closer look reveals ghoulish, two-dimensional beasts clawing at partygoers, and a figure, hair pulled into sharp horns, ordering a drink. In the context of Felix, Greene’s work was a funhouse mirror, a painterly distortion of an upper-crust social event that mixed the human with the monstrous.

This mingling of beast and man draws a curious mixture of identification and repulsion, a phenomenon that turns ordinary life into a theatre of its own. The Other is the viewed, not the viewer, on the street or in the circus tent. Early ringmasters like Barnum exploited this dynamic—and the persons they put on view—for their sideshow acts, manipulating the mere existence of Othered bodies (even creating them, through costuming and stage makeup) into performances in and of themselves. At Francois Ghebaly, Sharif Farrag’s imaginative ceramic vessels combined elements of the fantastically monstrous with the circus. In Juggler Jug (2021), a man-jester-wolf perches atop a pitcher laced with spiny tentacles and anemone-like protrusions.7As the title suggests, the character on the jug’s lid is suspended mid-act, ready to juggle the small props placed in his hands. Farrag was in good company: TARWUK (Matthew Brown), Lila de Magalhaes (also Matthew Brown), Melvino Garretti (Parker Gallery), and Joel Dean (Bel Ami) also mixed the inhuman with the real in settings that emphasized their characters’ theatricality. Artists favored stock types and caricatured facial features over the traditional, realist tendency toward likeness portraiture. At Felix, the beholder of each piece was a presumed circus attendee, turning men into wolves and ceramic jugs into miniature sideshows.

Adam Alessi, Acrobat, 2021, oil and flashe on canvas, 8 x 6 inches (20.3 x 15.2 cm). Image: Ed Mumford, courtesy of M+B Gallery.

Adam Alessi, Fictitious Spectator, 2021, oil and flashe on canvas, 36 x 48 inches (91.4 x 121.9 cm). Image: Ed Mumford, courtesy of M+B Gallery.

Adam Alessi (M+B) took the unspoken theme quite literally. In Acrobat (2021), a white-faced clown peers down at the viewer, its face pressed against the imagined wall of the small canvas. Heavy makeup cakes the figure’s face, its lips stretched red over the bottom third of the painting. Alessi’s Fictitious Spectator (2021) pictures a hunched character with a tall hooded hat and white, hook-nosed mask emerging from an opaque pink background, a slight smile visible above his ruffled circular collar. The figure is reminiscent of commedia dell’arte’s Pulcinella, one of four original stock characters known for his twin personalities: that of a cunning, witty thief from the upper class, and a bumbling clown of the servant class.8It’s an apt metaphor for most of Felix’s artists this year, playacting for an established collector base and their peers at the same time. The display of unreal, performative characters created a reflexive viewing experience, each fair attendee unwittingly deployed into carnivalesque scenes.

Polichinelle, ca. 1680 by French artist Nicolas Bonnart. The first of a set of five etchings entitled Five Characters from the Commedia dell’Arte.

The work on view at Felix—and the larger structure of the “Hollywood” art fair—turned the Roosevelt into a variety show that privileged outlandish and imagined models of human types and behaviors. This type of performance, the kind that gestures toward highly constructed, comically “wrong” ways of living, serves a different social function from art and exhibitions intent on revealing deeper humanistic psychology (think the Marx Brothers versus Death of a Salesman). At the circus, superficial tenets of civility are affirmed in the witnessing of their opposite: clowns, for example, locate humor in their violations of normative behavior—squeezing into tiny cars, attempting to woo taken women, or compulsively squirting water at their superiors.9By forcing the audience to notice social and cultural transgressions, the freak show’s “institutionalized social process of enfreakment united and validated the disparate throng positioned as viewers.”10The audience was joined together by the permission to recognize Othered types, either by behavior or appearance, a permission that granted a wide swath of people the “purchased assurance that they [were] not freaks.”11By focusing on action, gesture, and caricatures, performances created spectacle through the violation and consequent recognition of norms.

Historians link the structure of the circus or freak show to a medieval ritual called charivari, a masked procession that loudly mocked a person guilty of social wrongdoing.12Sometimes the performer was someone who had actually committed adultery or robbed a store, but more commonly an actor would imitate such indecencies for the parade.13The procession, too, engaged in uncivilized performance, clanging kitchenware and metal implements together (in England, charivari was called a “skimmington,” named after the ladle onlookers used to bang on pots).14Charivari used the ritual space as a controlled release of socially outcasted behaviors, employing both performers and onlookers in cathartic charade.

Art fairs, in form, are ceremonial events: fairs like Felix occur around the same time every year, each with its own fanfare and late-night revelry, allowing for a ritual engagement in social indecency alien to the uptight white-box gallery space—drugs, sex, extravagant public spending. At Felix 2021, consumerism, debauchery, and vanity were on full display. QR codes linked to price lists. Floor-to-ceiling mirrors lined cabana walls. Gallerists wore baseball caps with “DEALER” on their brims. In an art world marked by rigorous behavioral expectations, the fair is an abnormality. It serves a social purpose akin to charivari or freak shows: in providing an outlet for indulgence and so-called indecency, the art fair paradoxically affirms its no-touching, no-yelling, no-liquids-in-the-gallery opposite.

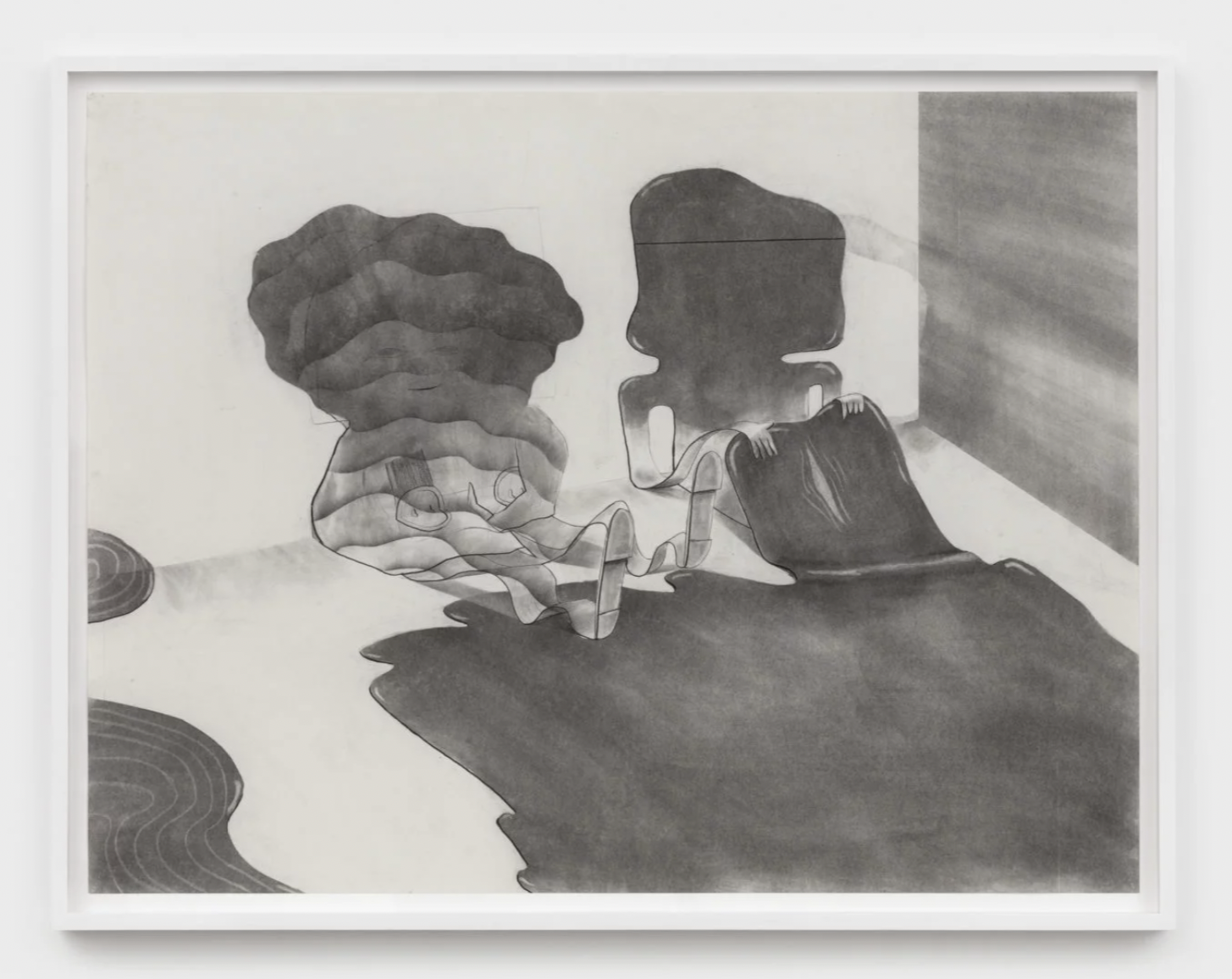

But the performance of incivility, even in its comedic, clown-like forms, demands something extreme from its participants. Where artists like Alessi and Farrag showed characters embodying Othered selves with the appearance of ease, more works took a darker turn. Meriem Bennani’s Clown chatting with sweet and sour B.O. puddle (2012), exhibited at CLEARING, depicts two cartoonish, two-dimensional forms, one of which appears to be a former clown. The “clown” can be distinguished by a pair of sunken eyes and comically large buttons, presumably the remains of a costume with suspenders. The body of the clown, seated upright against a wall, collapses into the earth, its legs and oversize shoes flopped on the ground. This is the clown after the show, inhuman, decomposing.

Meriem Bennani, Clown chatting with sweet and sour B.O. puddle, 2012, black pencil and charcoal powder on paper, 38.25 x 49 inches. Courtesy of the artist and CLEARING.

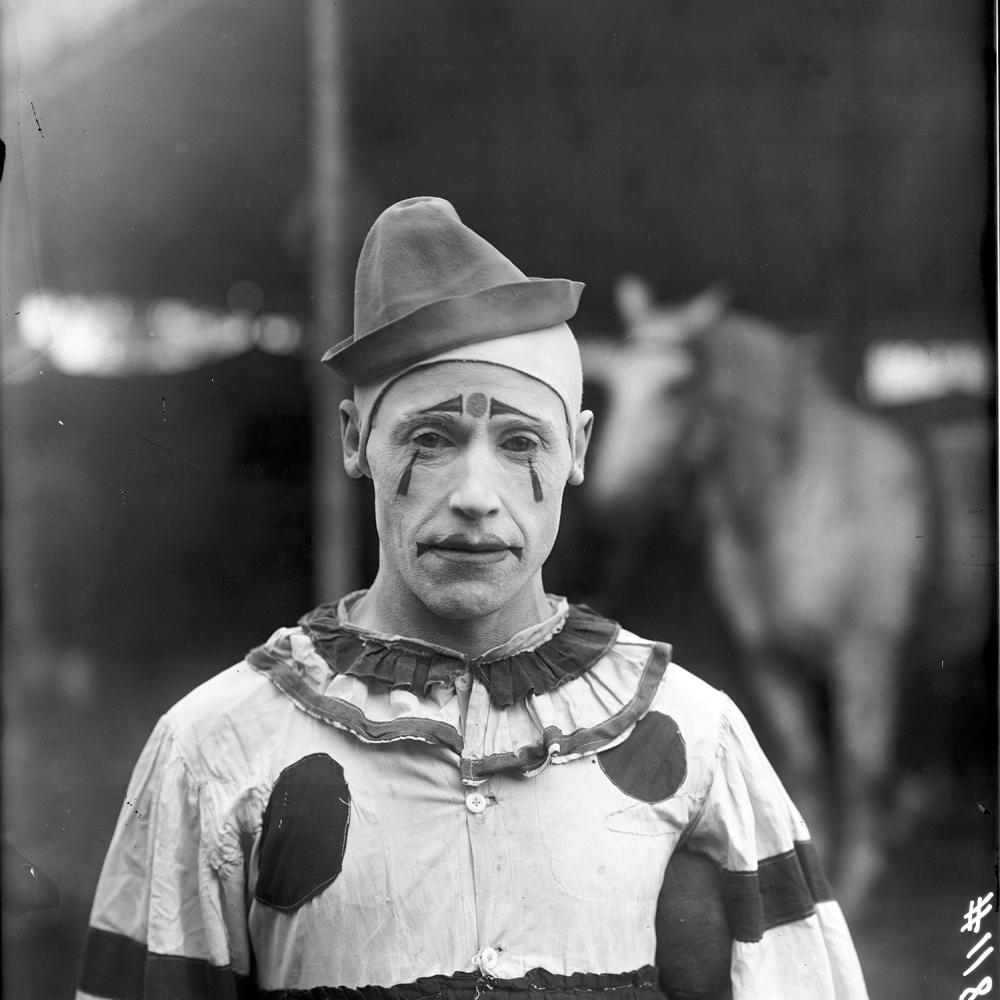

Clown portrait, circa 1902, from American Experience: The Circus. Collection of The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida, Florida State University.

The masks in Melvino Garretti’s “ecstatic” ceramics at Parker Gallery revealed similar consequences of a life lived onstage.15In Guess There Was Two of You (2015), multiple sides of a mounted “mask” depict two separate faces, one with a single eye and protruding white teeth, the other with a large yellow nose and an extended, petulant red tongue.16Appendages stick to the flat surface of the mask, separate from the totality of the face. Each feature has a life of its own: the tongue clings to a pair of closed lips, eyelashes stick to the figure’s forehead. Garretti’s masquerade rejects cohesion, even of the human body. In Bennani and Garretti’s work, performance comes at the individual’s expense.

Sometimes the line between onstage and off blurs. Sometimes the blurred line has deadly consequences. The Bal des Ardents, or “dance of the wild men,” was a type of charivari performed in 14th century medieval Europe.17Dancers covered themselves in fake, shaggy hair, meant to emulate the appearance of so-called “men of the woods.”18During the dance, they worked themselves into a loud, manic frenzy, engaging audience members in their act. In one 15th century chronicle, the Bal des Ardents was dubbed “una corea procurance demone,” or “a dance to ward off the devil.”19By imitating demonic behavior, the participants hoped to banish it. On January 28, 1393, the court of King Charles VI staged the Bal des Ardents at the Hôtel Saint-Pol in Paris.20In this case, the demonic exorcism of the charivari was not just abstract: King Charles VI suffered from what scholars now believe to be paranoid schizophrenia. The king had taken ill that previous summer, known to howl “like a wolf” (or a wild man) down the castle’s long corridors.21That night at the royal residence, Charles VI was secretly one of the Bal des Ardents performers—his confidants hoped the dance would cleanse him of his “madness.” But the performance took a turn for the worse when Louis I, Charles VI’s brother, brought a lit torch into the dining hall. The wild men’s costumes, made of wood, linen, and resin, caught fire. Four of the actors burned alive. The widely chronicled event was a turning point in Charles VI’s tenure: the public saw the catastrophe as symbolic of the king’s detachment from reality, deeming him unfit to rule.

Le Bal des Ardents, illuminated miniature from Jean Froissart’s Chroniques, sourced from British Library Harley Collection.

The hyperbolic performance of the costumed characters at the Bal des Ardents offered an opportunity for symbolic social investment: Charles VI’s court believed the dance could cathartically rid their king of his mental illness. Following the disaster, the king’s subjects instead saw the event as an allegory for the actual chaos, detachment, and violence they experienced as citizens under his rule. The leap between the performance of violence and the reality of it is sometimes quite small, an observation similarly noted by painter Sara Issakharian at Tanya Leighton’s Felix showing, where the artist used theatrical types—like the clown, or the lion—to create what Dr. Shiva Balaghi calls “visual narratives of social violence.”22In Lost Prayers On a Hot Summer Day (2021), a large beast with a lion’s mane tramples a figure with brightly rouged cheeks. A suited figure rides the animal clothed in a button-down suit with a ruffled collar, the most prominent of his or her facial features a long, pointed nose.23 The crushed clown, her mouth open in a scream, buckles under the weight of a smaller version of the genteel figure guiding the lion.24The clown wears no clothes, a stark contrast to the rider’s finery. Underneath the high drama of Issakharian’s work are violent class dynamics, an act that transcends the parts her characters play. In Issakharian’s paintings, clowns don’t just slip on a banana peel. They slip, fall, and die, usually at the hands of soldiers or regal-looking horseback riders. The difference between the mimicking of brutality—as in a clown’s slapstick or a medieval charivari—and actual brutality collapses.

Christopher Pearse Cranch, Burning of Barnum’s Museum, July 13, 1865, 1865, chromolithograph, Eno Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library.

P.T. Barnum’s American Museum burned down not once but twice, in 1865 and 1868. In the first, two whales boiled alive, and rumors circulated of a singed lion roaming the streets of Manhattan.25 Show business has more contemporary, local consequences, too: the Roosevelt is known to be haunted by more than a few ghosts, from Marilyn Monroe to Montgomery Clift.26Monroe died in Brentwood of a barbiturate overdose less than three months after she was fired from Something’s Got to Give—people on set claimed she was “willfully disruptive.”27It was difficult not to leave Felix thinking that something must give. It seemed to operate as a ritual catharsis of the art world’s more deleterious qualities; from Farrag’s dancing juggler to Issakharian’s tortured clowns, the fair’s freak show demonstrated the highs and lows of the burlesque experience. Hey—one way to rid ourselves of demons is to imitate them. Just don’t fly too close to the flame.