Democracy of Feeling: Auratic Artists’ Books at the Women’s Graphic Center

by Sam Regal

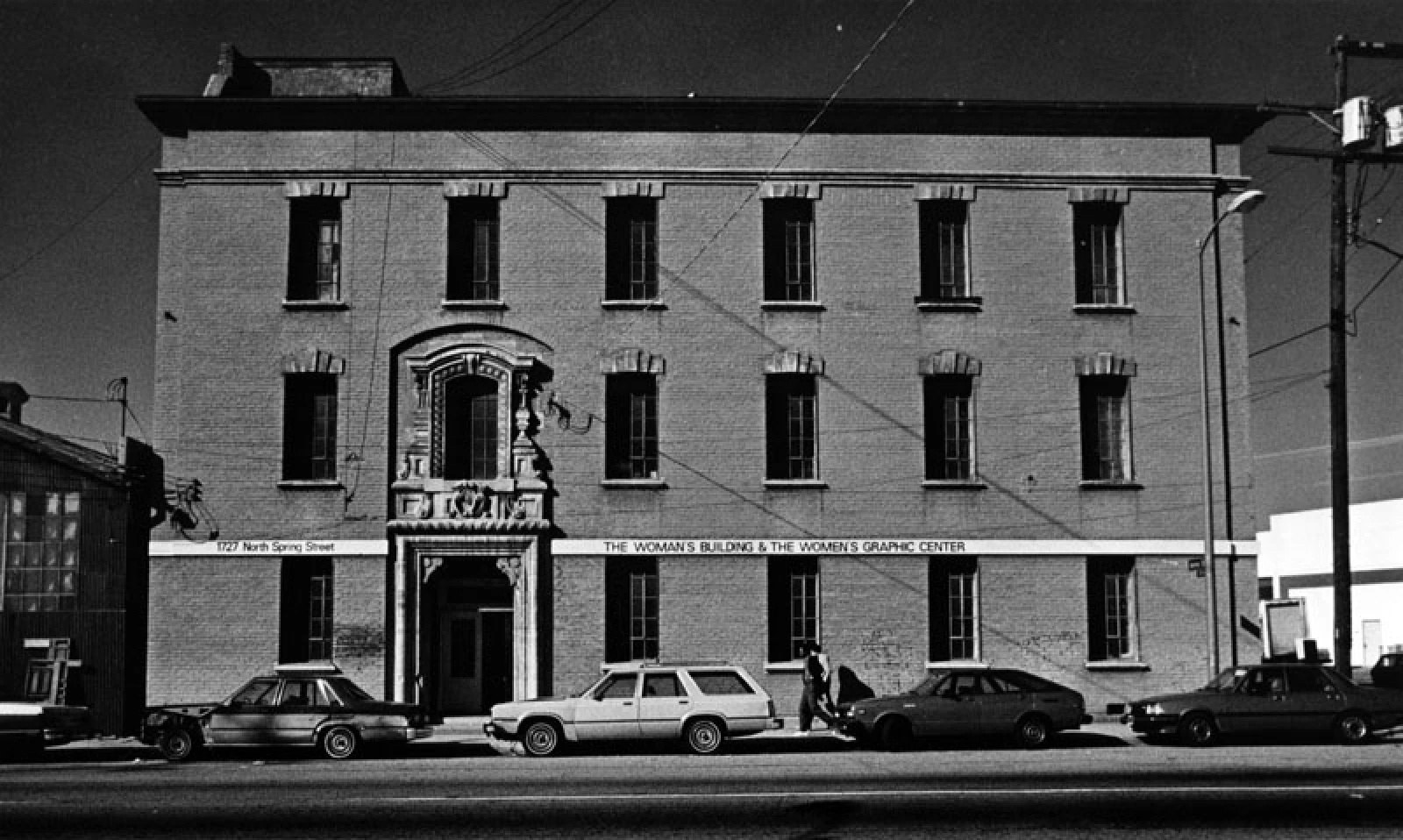

The Woman’s Building, North Spring Street, Los Angeles, photographed in 1983 by Chris Gulker, courtesy of the Herald-Examiner Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

In 1971, Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro established the Feminist Art Program at the newly formed California Institute of the Arts (CalArts).1 Its curriculum was envisioned to articulate and activate the core principles of a feminist art education,2and its impact reverberated within and without its institutional positioning. In the year following the Feminist Art Program’s formation, its founders hosted the West Coast Women Artists’ Conference at CalArts and organized Womanhouse, a month-long exhibition of collaborative, exploratory installations and performances staged within a dilapidated Hollywood estate.3These initiatives catalyzed a surge of feminist creative activity nationwide, and the Feminist Art Program began to strain at its institutional confines.

In its early years, CalArts cultivated a blossoming hostility toward feminist artists and arts education. Its faculty was nearly entirely male, and though the Feminist Art Program was afforded a position in the School of Art curriculum, the work was increasingly met with antagonism and suspicion. Judy Chicago immediately bristled at her institutional milieu, later recalling, “After all, I HATED CalArts and after one year unto my two-year contract, tendered my resignation.”4Chicago wrangled two similarly disillusioned colleagues to leave CalArts and form a standalone educational initiative exclusively for women artists. Chicago, Sheila de Bretteville, and Arlene Raven established the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW) in 1973, holding their early meetings in the decidedly domestic space of de Bretteville’s living room.

Wanda Westcoast,“Womanhouse: Nurturant Kitchen, Curtains,” 1972. CalArts Library & Institute Archives. Kitchen painted pink. Eggs turning in to breasts were cast in spongy material and painted realistically.

As the FSW developed, the need for a dedicated instructional space became apparent. The founders rented the former Chouinard Art Institute building, near MacArthur Park, as a more permanent home for the group.5The Woman’s Building was thus established, and, as the FSW built out the space to suit their needs, the community stretched into numerous creative and commercial directions. In her 1975 artist’s book The Woman’s Building Chicago 1983 / The Woman’s Building Los Angeles 1973-, Maria Karras describes the evolution of the space:

The Building continues to be a place of participation in the arts, collaboration of women in a variety of cultural and social activities and a place of exchange of women’s services. The community in the Building has expanded and now includes the Feminist Studio Workshop; the Extension Program; the Summer Art Program; the Woman’s Graphic Center; the Woman’s Switchboard; Womantours; Sisterhood Bookstore; seven galleries […] and Dr. Susan Kuher, feminist psychologist.6

The Women’s Graphic Center (WGC), a community studio outfitted with an offset press, a letterpress, metal type, and an area for screen printing, was at once a propagandizing initiative, a commercial venture, and a flashpoint of development of the artists’ books tradition. Print activity and self-publishing were central concerns of the feminist art movement, embraced as means of disrupting the canonically hetero-masculine perspectives represented by mainstream art and academic writing. Artists at the Woman’s Building utilized the resources at the WGC to produce posters, newsletters, postcards, broadsides, poetry chapbooks, and artists’ books. As artist Susan E. King described it, “Printing gave work power and distance”;7for feminist creative activity and community to thrive, publication was essential.

Bookworks

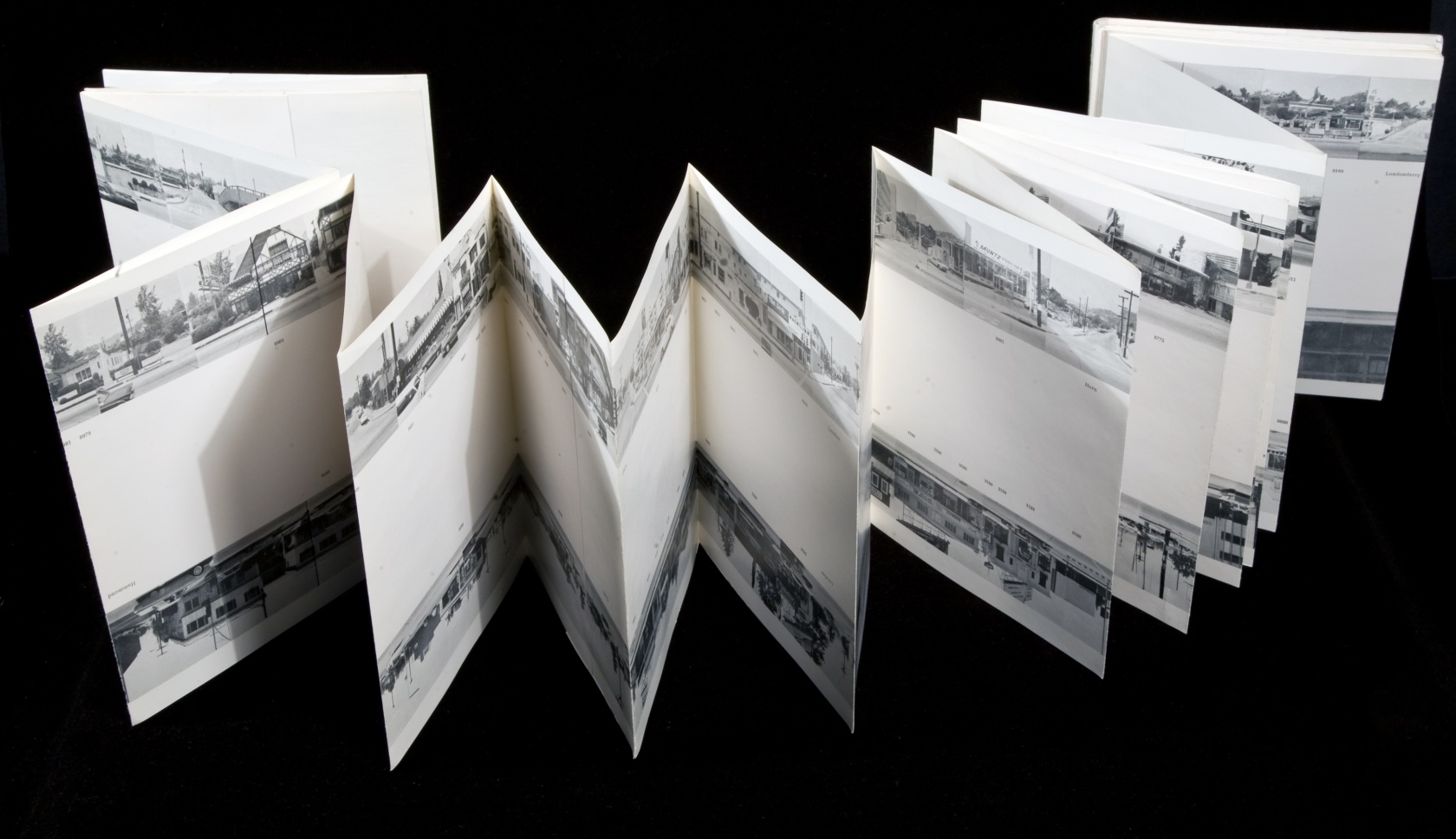

Ed Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966. CalArts Library Artists’ Books Collection.

The Women’s Graphic Center’s contributions to print culture in Southern California occurred in confluence with the concretization of the artists’ books movement. In 1973, as the Feminist Studio Workshop found its footing,8Philadelphia’s Moore College of Art9opened “Artists Books,”10a survey exhibition of book work generated between 1960 and 1973. The term “artists’ books” was previously used interchangeably with livre d’artistes;11the Moore College exhibition is regarded as a touchstone in the global recognition of artists’ books as a unique, developing artform.12The exhibition featured over 200 works by (chiefly male)13artists across genres, including choreographer Merce Cunningham, musicians John Cage and Steve Reich, and visual artists Ed Ruscha, David Hockney, and Dieter Roth.14

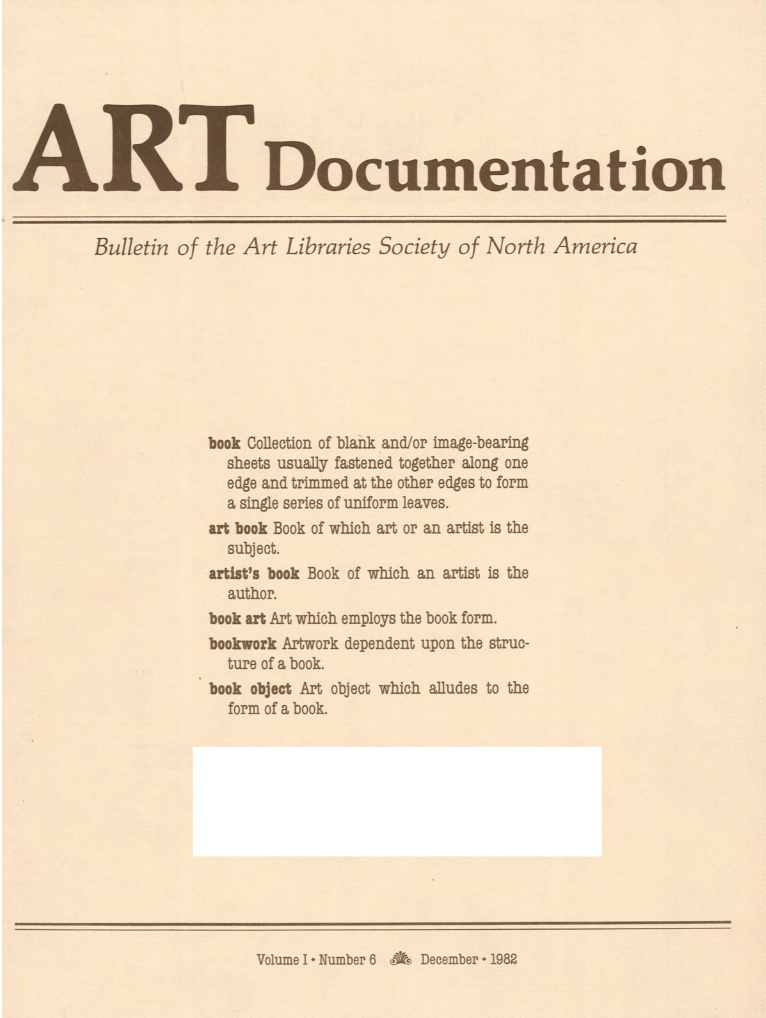

Given their inherent interdisciplinarity and regular conceptual properties, artists’ books tend to resist tidy definition. In 1976, Museum of Modern Art librarian/curator Clive Phillpot defined “book art” as “books in which the book form is intrinsic to the work.”15This essential attentiveness to book-ness is now commonly ascribed to artists’ books. Phillpot later delineated between types of book art on a 1982 cover of Art Documentation, the premiere art librarianship journal:

book Collection of blank and/or image-bearing sheets usually fastened together along one edge and trimmed at the other edges to form a single series of uniform leaves.

art book Book of which art or an artist is the subject.

artists’ book Book of which an artist is the author.

book art Art which employs the book form.

bookwork Artwork dependent upon the structure of a book.

book object Art object which alludes to the form of a book.16

Cover, Art Documentation: Bulletin of the Art Libraries Society of North America 1, no. 6 (December 1982).

These definitions, while clarifying, are intensely reductive. Of interest is Phillpot’s positionality as arbiter of categorization among art librarians. Classification is a fundamental tenet of librarianship, despite the violence embedded in its tendencies toward simplification and elision. As an art librarian myself, I negotiate these contradictions in my daily professional practice. I delight in artists’ books’ essential resistance to the rules and requirements of my job—to the maintenance of an organized, accessible, basically beneficent intertext of knowing. My fond anarchic world is irreflective of the dispassionate comprehensibility of library stacks; the art I love is blissfully irreverent of the Library of Congress Classification System.

Artists’ books are more than their authorship. Regarded by many critics as a democratizing medium, these artworks hold accessibility and autonomy among their dominating characteristics. In her 1977 essay “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” critic Lucy Lippard offered:

Neither an art book (collected reproductions of separate art works) nor a book on art (critical exegeses and/or artists’ writings), the artist’s book is a work of art on its own, conceived specifically for the book form and often published by the artist him/herself. […] Usually inexpensive in price, modest in format, and ambitious in scope, the artist’s book is also a fragile vehicle for the weighty load of hopes and ideals: it is considered by many the easiest way out of the art world and into the heart of a broader audience.17

Artists’ books allow for a creative autonomy that traditional gallery and museum exhibitions cannot afford. The form’s development was closely tied to the concept of the democratic multiple, wherein artists control the means of production, issue their work in edition, and distribute their artists’ books directly to the public.18In the same essay, Lippard proposed, “One day I’d like to see artists’ books ensconced in supermarkets, drugstores, and airports and, not incidentally, too see artists able to profit economically from board communication rather than from lack of it.”1920It stands to reason the separatist artists of the Feminist Studio Workshop would find this alternative system of distribution appealing.

Of course, artists’ books are not always produced affordably, or in edition. Many works are unique, rare, even fetishistic,21activating the so-called auratic qualities of one-of-a-kind pieces of fine art and falling perhaps more neatly within the long tradition of the fine press. Therein lies the implicit reductive violence of definition. The form is expansive, challenging classification by design, and formally varied; some of my favorite artists’ books don’t look like books very much at all.22An irreverence toward the codex challenges notions of what knowledge is and looks like, and forces critical reflection about the ways we receive, transmit, and codify knowing. In my professional effort to make these artworks accessible, I’m forced to obliterate their complexities, their potentialities, the fount of their power.

Engagement with rare or unique artists’ books can be a sensual, affectively-charged experience. Per Benjamin, an artwork’s aura, or the experience of a unique artwork in time and space, contributes to its expressive impact.23Scholar Charles Altieri proposes “rapture” as a descriptor for this type of impassioned aesthetic encounter.24The physical experience of an artwork—holding a unique artists’ book, turning its pages—serves to heighten felt sensations, affording them emotional and temporal resonance.25Rarity is not, however, an absolute requirement of affective activation. As scholar/writer/book artist Johanna Drucker26acknowledges, editioned works with handwork and elaborate production elements can also hold auratic qualities.27

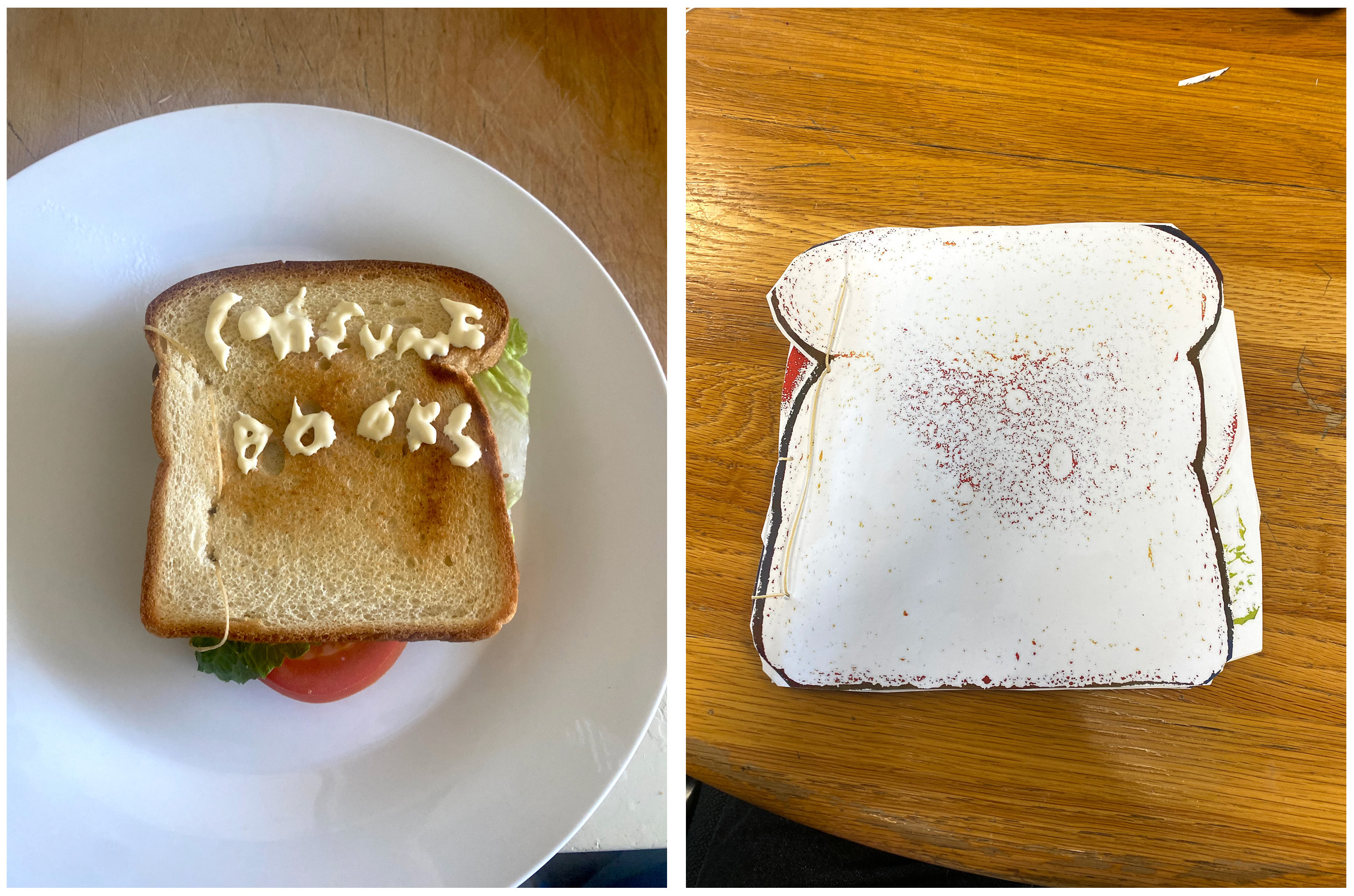

Sampson Ohringer, BLT in Two Volumes: An Investigation of Representation and Materiality, for “Art of the Book” course instructed by Sam Regal, CalArts, 2023. Bread, mayonnaise, bacon, lettuce, tomato, waxed thread, inkjet printer paper.

An artist’s book produced in endlessly duplicable democratic multiples would not, by this logic, hold meaningful affective charge. Benjamin suggested that while a reproduction may reach more of the public, the process of replication irretrievably depletes the original work’s authority and “cult value.” This auratic decay, he notes, can increase a work’s social value: “the technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. And in permitting the reproduction to meet the beholder or listener in his own particular situation, it reactivates the object reproduced. These two processes lead to a tremendous shattering of tradition which is the obverse of the contemporary crisis and renewal of mankind.”28Reproduction can create the conditions necessary for social upheaval, but it causes an artwork’s aura—a source of potential affective impact—to collapse.

Benjamin may have stopped short of extending his argument to books, having previously expressed his affinity for book collecting.29In No Longer Innocent: Book Art in America, 1960-1980, Betty Bright expounds upon this point: “In multiple, [the artist’s book] supports Benjamin’s belief in unfettered access to mass art forms. But in reading a book, its status alters into one of a personal, auratic object of cult value.”30Bright gestures toward a complex tension intrinsic to the book form. Regardless of their scope of distribution, books have the potential to produce limitless intimacy.

Reading, or otherwise encountering knowledge in the book form, is a contained, internal process with deeply personal affective resonances. Unique artists’ books and those produced in editions may each be rich with affective potential, but the rarified, auratic book object tends to generate a distinct emotional immediacy. Distinctively, many of the book artists at the Women’s Graphic Center chose to bridge these poles, creating work in multiples with unique, emotionally expressive elements that connected the blossoming artists’ books tradition with major themes of the feminist art movement.

Feelings in Multiple: The Women’s Graphic Center

Sheila de Bretteville and her second-wave feminist contemporaries believed in the necessity of bringing elements of their private lives into the public sphere. In the original program description of the Women’s Graphic Center, de Bretteville wrote, “Once a woman is able to locate and articulate a connection to the public world, she is able to feel more responsible and caring toward it.”31To de Bretteville, the act of artmaking was an extension of care. Care, emotion, and affective experience—distinct from the saccharine and sentimental—are themes of the feminist art movement; artists tended toward autobiographical and sexual description, integration of elements of the domestic, and recontextualization of traditionally feminized craft to affirm and validate the realities of women’s experience.3233In 1976, Lucy Lippard wrote:

Why are we all still so afraid of being other than men? Women are still in hiding. We still find it difficult, even the young ones, to express ourselves freely in large groups of men. Since the art world is still dominated by men, this attitude pervades the art that is being made. In the process, feelings and forms are neutralized.34

Feminist separatism was adopted as a solution to the stultifying male dominance of the art world, and was a fundamental tenet of the establishment of the Woman’s Building. de Bretteville formed the print arm of the building as an extension of this purpose: “It is the intention of the Women’s Graphic Center to provide the education, equipment and support necessary for women to make the bridge from the personal to the public world.”35At the FSW, de Bretteville taught a popular course, Feeling to Form, that led to a significant wave of graphic output.

Helen Alm, the Women’s Graphic Center’s first director, acquired equipment from a defunct letterpress shop and engaged her students with her collection of artists’ books and fine press materials. The WGC’s curriculum focused on collective expression and self-publishing, utilizing the mimeographic offset and diazo printing methods rather than traditional fine press print techniques like lithography and etching, the latter considered inappropriately individualistic. The artists at the WGC came to strike a characteristic balance between a sociopolitical commitment to accessible work in multiples and engagement with Californialia, fine printing, craft, and the auratic book object, as was evident from the earliest days of the WGC. Susan King recalled a formative engagement with these simultaneous traditions:

I remember more vividly sitting on the stairs of the Woman’s Building and having Helen Alm, the first director of the Women’s Graphic Center at the Woman’s Building, hold up an Ed Ruscha book and one by Jane Grabhorn. Jane was a wacko printer from Northern California […] She was married to Robert Grabhorn, who did fine printing, but she used the Jumbo Press to poke fun at the pomposity of it all. When I first started learning letterpress, I looked at her work a lot […] Later, when I got more interested in letterpress, I started looking at the history of fine printing in California.36

California print tradition is distinctive for a fundamental, pseudo-isolationist idiosyncrasy, a characteristic determined largely by its geography. By the 1930s, California printers were widely considered woefully passé, owed to their distance from “the vitalizing atmosphere that is always present in localities where a craft is always practiced.”37This separation from nexuses of mainstream print activity caused an unfashionable fixation on the Arts and Crafts style among California printers through the 1930s, but ultimately catalyzed bursts of original activist and artistic print work in the decades that followed. Self-publishing is a major thoroughline of California print activity, linking directly to the zine, anarchist/punk, and DIY traditions of the later twentieth century to present. Though the California print tradition has its roots in the Bay Area, Southern California, its dusty, lawless cousin, cut a characteristically cowboyish figure of contrarianism throughout its history. Rather than adhere stylistically to the popular Arts and Crafts movement, a number of Southern California fine printers of the 1930s experimented with photography, graphic design, and distinctive ornamentation. This experimental ethos evolved throughout the century and was later articulated in the complexly hybridized artists’ books of the Women’s Graphic Center.

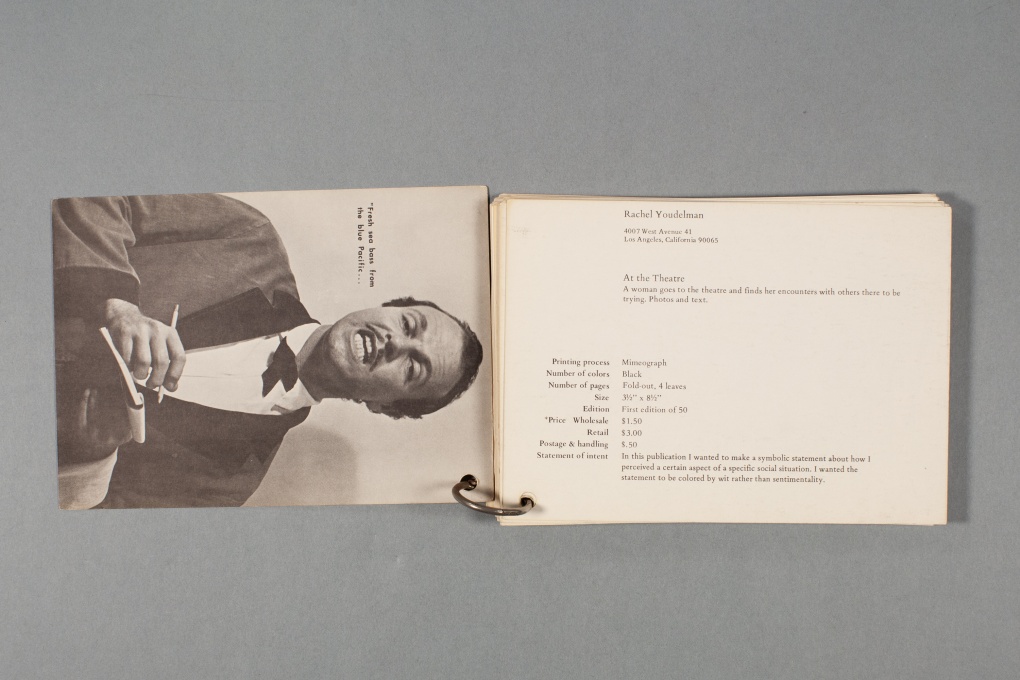

Susan King, a visual artist and member of the Feminist Studio Workshop’s earliest cohort, delighted in the idiosyncrasies of Jane Grabhorn’s Jumbo Press38—its “combination of freeform, highly individual content and tightly controlled and skillful craft”39—and Grabhorn’s exacting strangeness came to meaningfully shape her approach to artists’ books. Two of King’s books, Letter Portfolio and Passport, were featured in the Women’s Graphic Center’s 1977 catalog Women and the Printing Arts.40Designed like a library card catalog and bound by a single metal ring, this publication featured the book work of 22 artists and presses, the majority of whom were from the Los Angeles area and in direct or tangential association with the Women’s Graphic Center. Most of the artists’ books featured in the catalog are reproduced by offset printing, articulating the concept of the democratic multiple. The artists most associated with the Woman’s Building, in contrast, utilized more complex, hybridized production methods that imbued their works with heightened auratic impact.

Women and the Printing Arts: A Catalog, 1977. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Women and the Printing Arts: A Catalog, 1977, inside book. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

The CalArts Library’s Artists’ Books collection is host to the 1977 Women and the Printing Arts catalog, along with a number of books the catalog advertises. In my role as a librarian at CalArts, I serve as both caretaker, researcher, and evangelist for these materials.41My position also requires me to navigate the deep, historical problematics of the institution in which I’m situated. CalArts was an inhospitable environment for the Feminist Studio Workshop’s founders, and it was administrative hostility that encouraged the group to establish their separatist collective. The Woman’s Building’s resultant impact on the wider feminist art movement is incalculable, and CalArts now tends to emphasize its association with the building’s founders. The WGC-affiliated works in the CalArts Artists’ Books collection exist within a dense, intractable web of ownership, reduction, and recusal. Created in intentional ideological detachment from hegemonic institutionality and bursting with complexities, the artists’ books are reinstitutionalized in the CalArts Library and critically undermined in their description. The works fundamentally challenge systems of classification, and by making the works accessible, the library brutally diminishes their hybridity and mutes their affective impact. The preservation and promotion of these artworks are important—I believe this work is valuable and should be protected, shared, and celebrated; that the knowledge they represent is meaningful—but the irony of my position overwhelms. My hope is that CalArts’ full-throated embrace of this material provides the artists some satisfaction, if belated, if bitter.

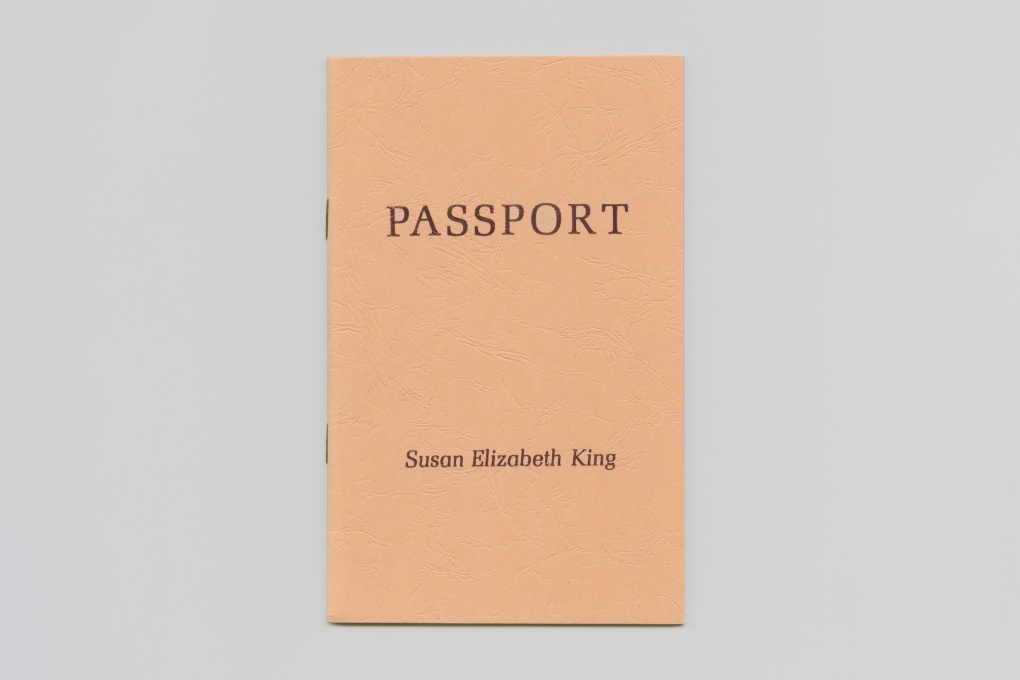

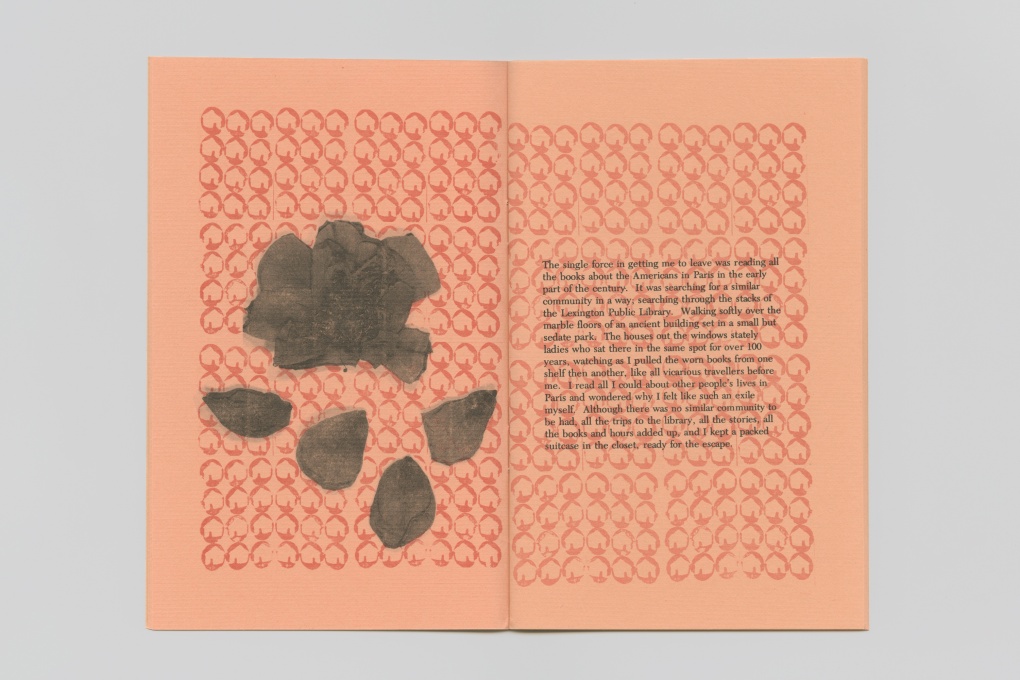

Susan King’s Passport (1976) is an evocative example of the uniquely hybridized artists’ books emerging from the Women’s Graphic Center’s productional orbit. King described the work in the 1977 Women and the Printing Arts catalog: “Travel as growth, as metaphor, as dream, as memory. Travel as departure, as arrival; foreign and domestic travel.”42The book’s cover has a texture reminiscent of a government-issued passport, and King utilized both offset and letterpress printing on its pages, breaking from the straightforward duplicability of the democratic multiple form. By integrating elaborate production elements, King nods to Jane Grabhorn and other printers in or adjacent to the fine press tradition. The finery of the book object also generates an auratic quality, which breeds emotionality. Engagement with the unique artist’s book is a rapturous experience, and the book’s contents are correspondingly affectively charged. In line with de Bretteville’s preoccupation with bringing the personal to the public, King saturates Passport with romantic recollections of loved places, loved objects, and loved people. The work radiates with humanity—it is deeply feeling and deeply felt.

Susan King, Passport, 1976. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Susan King, Passport, 1976, inside book. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

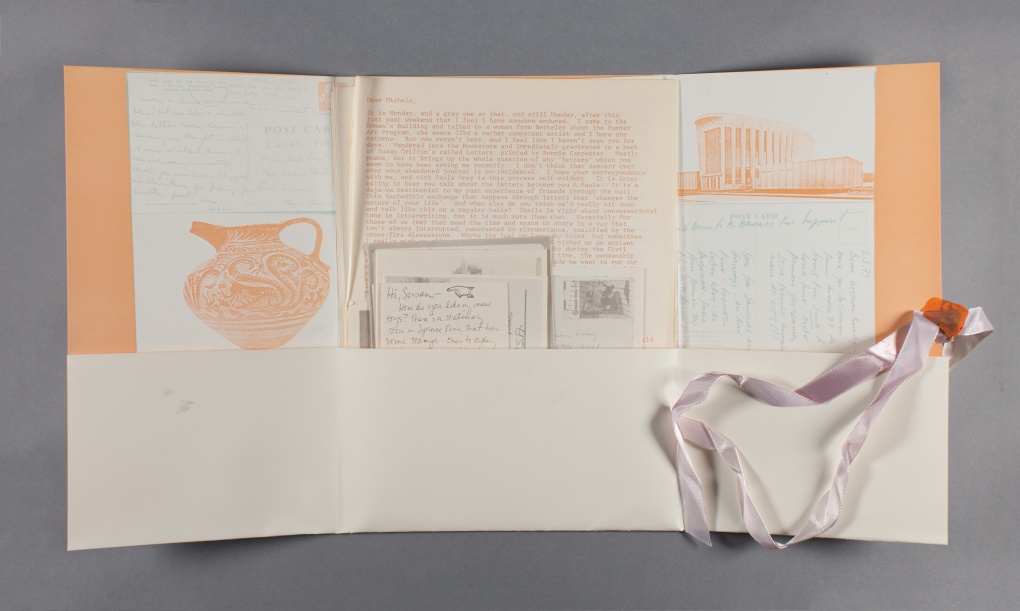

King’s Letter Portfolio (also 1976) eschews the standard codex, and, as its title implies, takes the form of a glossy portfolio folder filled with reproductions of postcards and letters. There is a luridity—even a voyeurism—implicit in the digging through the artist’s personal correspondence, but this engagement generates a deep intimacy, too. King describes the work as “The journal that never worked. It was in the letters, spread from Spain to Oklahoma, that chronicled my life.”43Letter Portfolio resonates with emotion and emotional potentiality, containing a telegram informing King of her father’s heart attack, a birthday card, meaningful professional correspondence, and other significant pieces of writing related primarily by hand. While the book is a multiple, its production is elaborate, and its cover is enclosed by a monogrammed wax seal. By the time I got my hands on CalArts’ edition of Letter Portfolio, its seal had been broken, presumably, for decades—another articulation of invasion. Once again, the rich emotionality of King’s personal life is brought boldly to the public.

Susan King, Letter Portfolio, 1976. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Susan King, Letter Portfolio, 1976. Letters. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Likely the most globally consequential artist’s book created in affiliation with the Women’s Graphic Center is Suzanne Lacy’s Rape Is (1972, 1976). Lacy, who followed FSW cofounder Judy Chicago to CalArts and printed the book at the WGC, described the intention of her work:

I see the book as an analogy for a woman who is in unity with herself when alone. The glossy white pages are jet life—clean, untainted by assumptions and perceptions of women. The intrusions are the black type, the constant recurring experiences which are forcibly placed in the center of each page, in the same way they intrude deeply onto a woman’s life. I want the reader to enter the book, enter forcibly, enter into a woman’s perception, and realize the ways in which women are raped, both psychically and physically.44

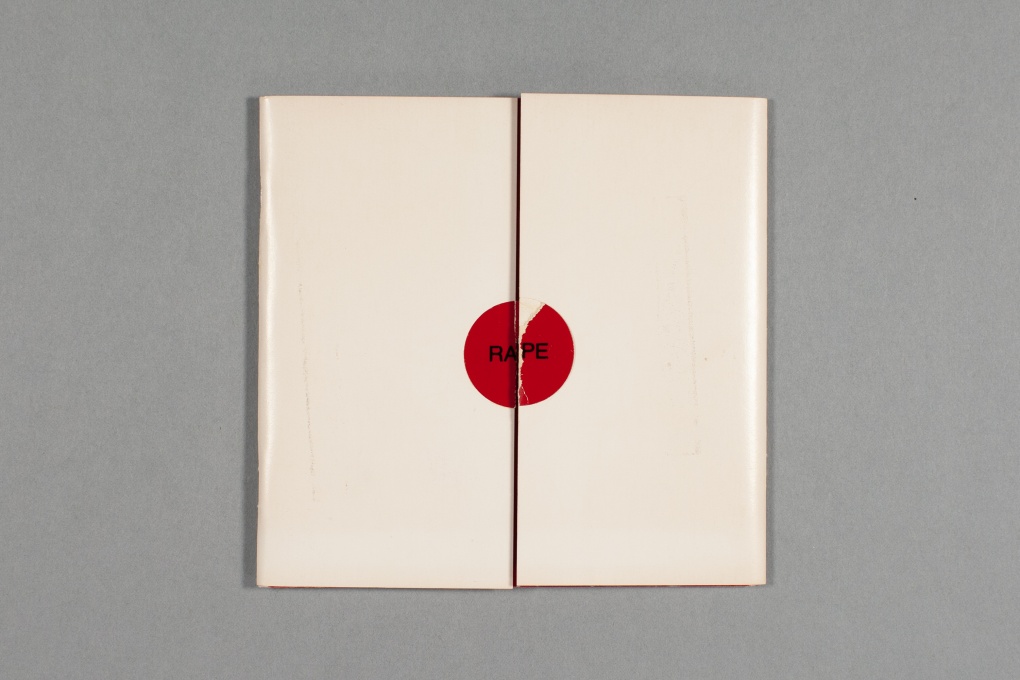

Suzanne Lacy, Rape Is, 1976. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

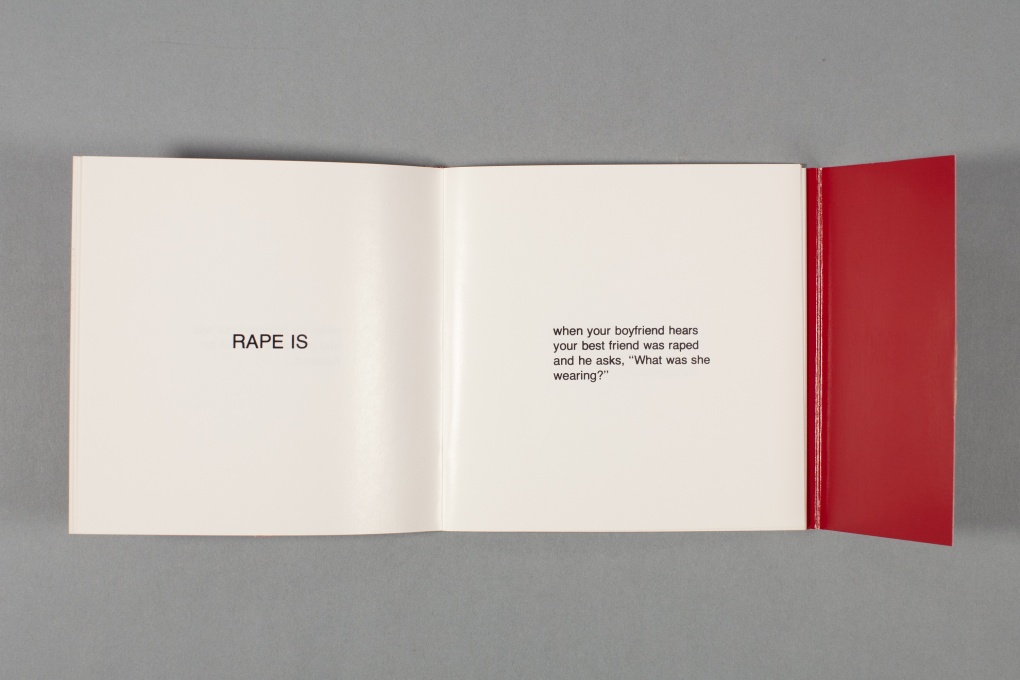

Suzanne Lacy, Rape Is, 1976, inside book. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

The artists’ book is sealed with a carmine sticker printed with the word “RAPE;” to access the book’s pages, the seal must be broken, mirroring the invasion of sexual assault. The seal on CalArts’ copy of this work was torn with some violence, marring its surrounding surface. The book’s cover is split down its middle, mimicking a vaginal opening, and on its pages, Lacy relates a nauseating spectrum of major and minor invasions. It’s a difficult work that demands participation, regardless of the reader’s willingness. Though 1,000 copies of the second edition were printed, Rape Is holds an unmistakable affective charge, not the least for the grotesquerie of its contents. Its intimacy—the personal, directed violence it requires—is felt, and once its seal is broken, there is an anguish for that which cannot be repaired.

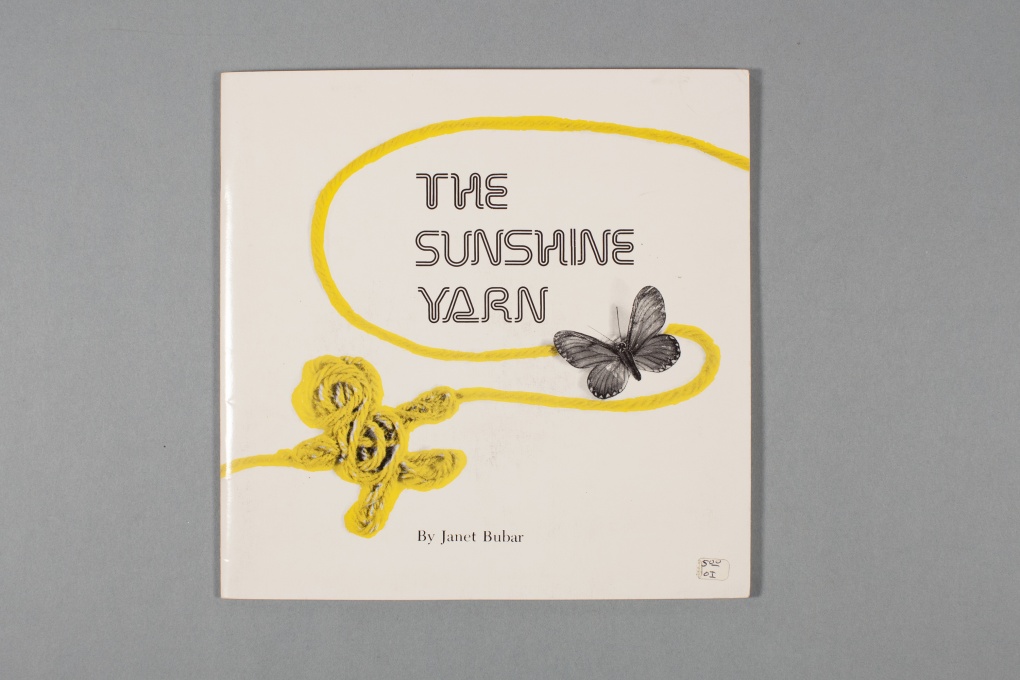

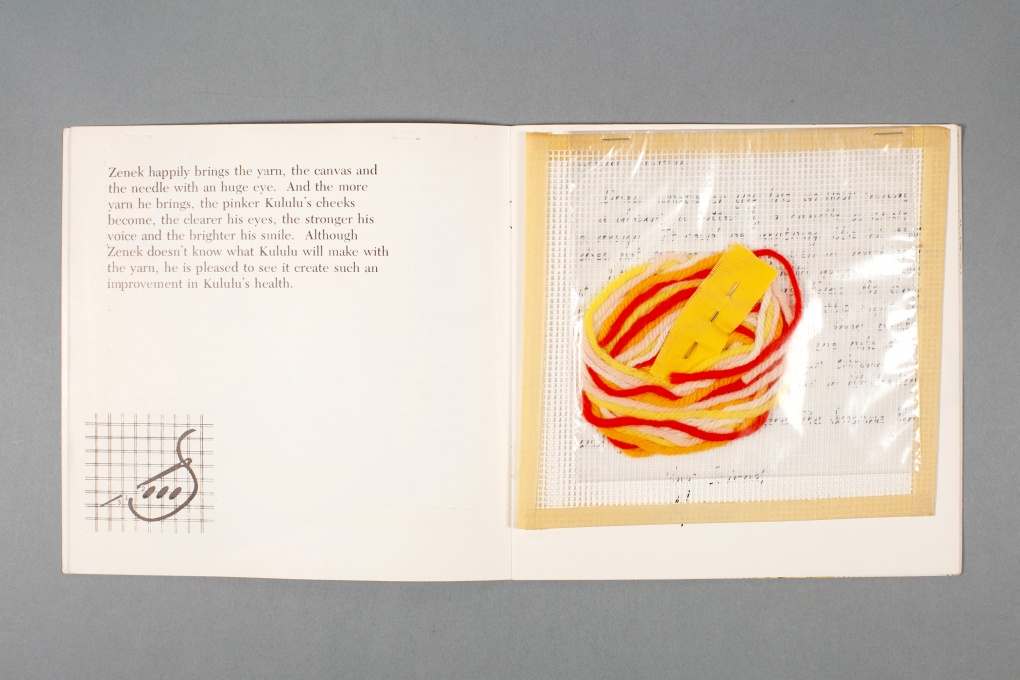

While the majority of artists’ books created in the Women’s Graphic Center’s milieu contain overt themes of social or political activism, there are exceptions to this rule. Janet Bubar’s The Sunshine Yarn (1976), printed at the WGC, is a children’s book that integrates elements of craft into a relatively straightforward fanciful tale. Bubar described the work as a “Story, yarn, for all children to enjoy—about a creative character in a wheelchair who creates joyful experiences for himself and others.”45The book has an insert containing a needlepoint kit, complete with a needle, colorful yarn, and instructions, encouraging the reader to create alongside Kululu, the book’s protagonist. The Sunshine Yarn integrates craft, the oft-diminished traditional domain of women, into an artist’s book with complex and artful print elements. The addition of the unique needlepoint kit contributes to the book’s auratic resonance, and it activates the affective experience brought upon by engagement with textiles and texture.

Janet Bubar, The Sunshine Yarn, 1976. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Janet Bubar, The Sunshine Yarn, 1976, inside book. CalArts Artists’ Books Collection.

Feeling Thinking

I spend much of my professional life puzzling through ways to afford institutional validation to complex articulations of knowledge. My thinking is mitigated, inevitably and inescapably and always, by feeling, and the linearity of much of the knowledge canon I work within is stifling. I delicately stumbled into librarianship from starving as a full-time, mortally abashed poet, and while my current vocation suits me, it contains unresolvable challenges. The best I can do is to collect works that challenge or defy knowledge convention and attempt to sidestep the violences of classification.46

Artists’ books contain such delicious multitudes. The book works of the artists at the Women’s Graphic Center represent a way of knowing that was, at the time, institutionally excluded and demeaned—until it wasn’t. These works are, in reality, intensely homogenous, reflecting the internal lives of white cis women with very few exceptions. The revolutionary vision of the founders of the Feminist Studio Workshop was specific, situational, and very much in line with second-wave feminists. Still, their creative contributions and community were impactful, translating value and validation to the representation of women’s emotional lives and personal experience. By articulating their emotional knowledge in the book form, the artists of the WGC expanded what information is and can be. I love to shelve these powerful feelings—charged, transtemporal, forever powerfully felt.