Henry Lovins and the Lost Hollywood Art Center School

by Elizabeth Lovins

Henry Lovins at his estate, c. 1949. Villa and studios built by notable architects Dennis and Farwell, c. 1904, photo: Leland Auslender. Unless otherwise noted, all images courtesy of the Hollywood Art Center Archive.

The Hollywood Art Center, an enchanting lost art school and gardens, was one of LA’s best-kept secrets for decades. Tucked away within a serene four-acre, 1920s Spanish garden and estate along Highland Avenue near the Hollywood Bowl, the school ceased operations in 2000 after the passing of its final director, my grandmother Mona Lue Lovins. In its final years, the school was in a severe state of disrepair, the buildings and grounds beautifully decaying within the picturesque setting of the Hollywood Hills and Whitley Heights.

At the time of its closure, the Hollywood Art Center could be entered by crossing the threshold of Highland Avenue through a long driveway located between the American Legion Building and the Best Western Motel at 2025 N. Highland Avenue. The rush of the Highland Avenue traffic would fade into the distance as you entered the secret villa’s studios and gardens, where the jasmine-scented grounds held an abundance of color, empty koi ponds, overgrown pathways, a crumbling colonnade, and a hillside shrouded in wild foliage.

Staircase to upper studios and guest house area, 2018, photo: Thomas Lawson.

At the rear of the property, studio classroom buildings and gardens were, until recently, packed full of student and faculty work representing over eighty years of art production. The studios had a lost-in-time quality: it could have easily been the 1940s, the school’s heyday. The smell of empty turpentine cans, paint palettes, oil paint, and clay permeated stacks of magazines, design boards, architectural renderings, drawings, and paintings. At every turn, there was something new to find in these layers of materials spanning almost a century of Southern California’s artistic history.

The villa was also full of artwork, furniture, books, papers, easels, films; the guestbook at the front door was still there to be signed by visitors arriving through the octagonal, Batchelder-tiled floor and fountain atrium room. An empty dragon chair sat next to a Mayan painted screen and a secret library to the left. Inside, there were more stacks of papers and books containing materials related to the school and its founder, my grandfather, Henry Lovins (1883–1960), as well as his circle of artists and the school’s connection to East Coast art institutions including the New York School of Fine Art.

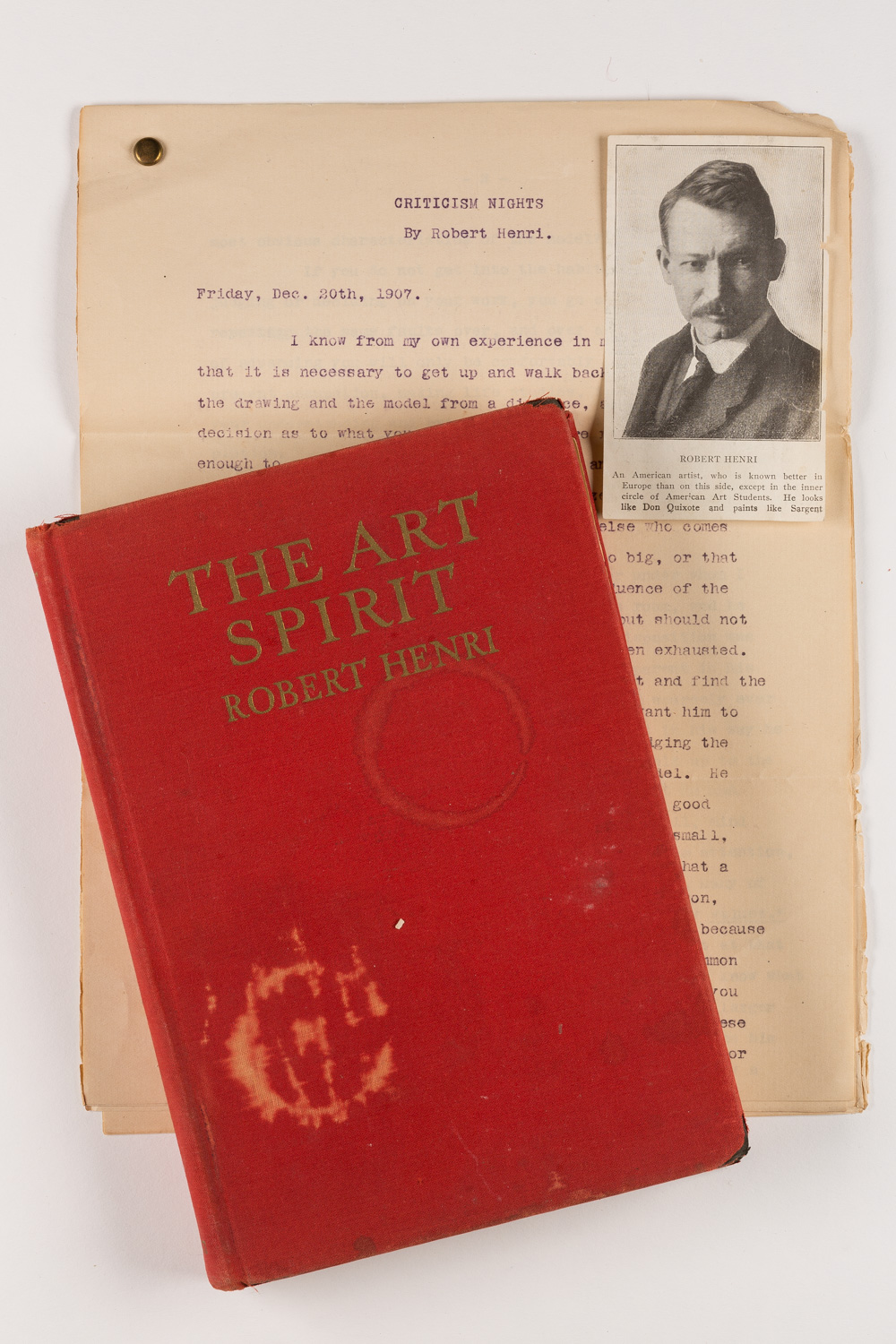

Established in 1912, the Hollywood Art Center School was LA’s first independent art school. Henry Lovins—an artist, educator, and interior designer—founded the school largely upon the teachings and philosophy of his personal mentor, Robert Henri. Henri, a prolific American painter, teacher, and leader of the Ashcan School, was perhaps the single greatest influence on the development of artists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.1 His philosophy was embodied in his 1923 book The Art Spirit, which Lovins used in his daily teaching practice. The Art Spirit is still one of the most important books used in art schools today, guiding students to create their own authentic works without pressuring them to follow one particular artist or school of thought.2

We are not here to do what has already been done. I have little interest in teaching you what I know. I wish to stimulate you to tell me what you know. In my office toward you I am simply trying to improve my own environment. Know what the old masters did. Know how they composed their pictures but do not fall into the conventions they established. These conventions were right for them, and they are wonderful. They made their language. You make yours. They can help you. All the past can help you.3

photo: Brett Cody Rogers

Lovins, born in Kiev in 1883 to a Jewish family, immigrated to New York City in 1887. Raised in New York, he moved to Denver as a young man. After studying there with artist Jean Mannheim, a well-known landscape painter and California Impressionist, he returned to the East Coast in 1904 and enrolled in the New York School of Fine Art, where he studied with Henri and William Merritt Chase. After graduating, he returned to Colorado and started the independent Lovins School of Art (1908–11) while also acting as the head of the art department at the University of Denver.

Although he found success in Denver as an artist and educator, Lovins soon became fascinated by the idea of moving to Southern California. He left Denver and journeyed west with the aim of pursuing his own artistic endeavors and cultivating world-class art instruction and mentorship within the Los Angeles community. He accepted a position as head of Painting and Drawing at the University of Southern California (USC) in the College of Fine Art, located in the now-historic Judson Studios in Highland Park.

Upon arriving in Los Angeles—already by then a rapidly growing center of culture and creativity—Lovins honed his ambition. He aspired to bring Henri’s philosophy and approach to teaching, and even Henri himself, to USC, and he saw an opportunity to attract other revered artists from the East Coast. Lovins lured Henri with an impassioned letter filled with promises of the vast possibilities for teaching and painting on the West Coast. He outlined a (failed) plan for Henri to take over the USC College of Fine Art from the aging—and as Lovins saw it, increasingly irrelevant—dean, William Lees Judson.4 He sent detailed descriptions of the landscape painting in California, as well as the multitude of “characters” and diverse ethnic populations one could paint portraits of.

This part of the country is beautiful to the extreme, and has a climate that is unexcelled anywhere, and as material to paint, you will be surprised at the unlimited amount and the variety that can be procured. If you want landscape, every imaginable phase can be found here, beautiful trees, rolling hills, rugged mountains, canyons, arroyos, stormy seas and rock bound coasts, deserts, etc., Also harbors, shipping and the atmosphere that goes with it. If you want characters, you can have the choice of any nation that exists in the Pacific Ocean and environs such as the Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, [sic]Hawaiians, Turks, Syrians, Greeks, Italians, Russians and especially Mexicans.5

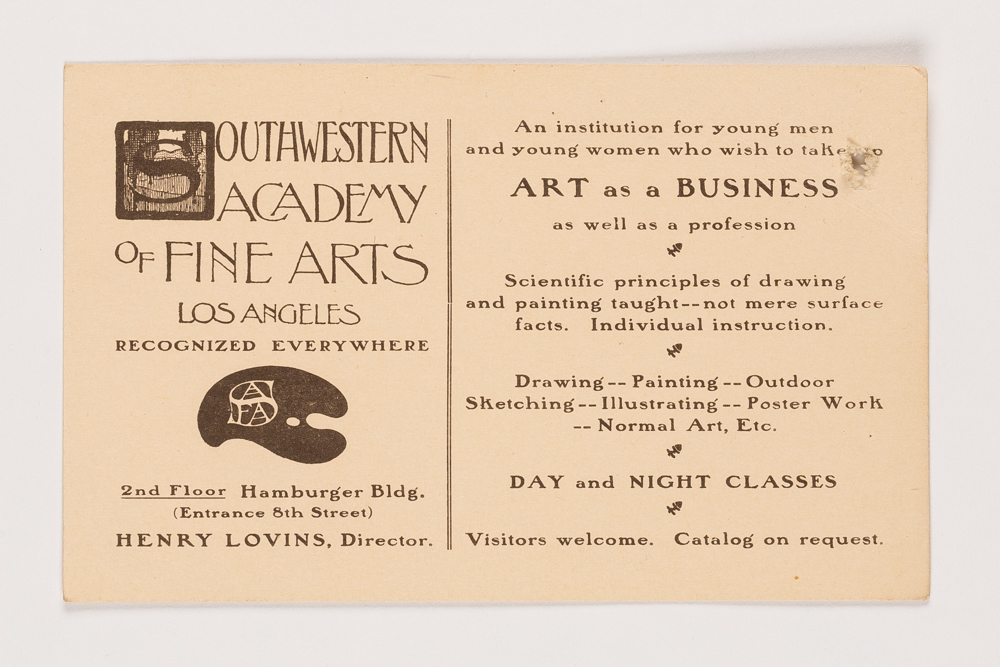

After realizing USC was not the right venue for what he had set out to accomplish, Lovins decided to strike out on his own. In 1912, he founded the first independent art school in Los Angeles on the second floor of what is now the May Company Building on Broadway—at the time, this building was also home to the A. Hamburger & Sons department store and the Los Angeles Public Library. What began as the Southwestern Academy of Fine Arts had many different names and locations over the years until finally, in 1930, it became the Hollywood Art Center School.

photo: Brett Cody Rogers

In his own art career as a painter, designer, and interior designer, Lovins made works inspired by pre-Columbian art and ancient American civilizations. After meeting archaeologist Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett in 1915, Lovins became fascinated with depicting ancient civilizations in his murals and interior design work. As one of the first artists in California to work in the Mayan Revival style, he was prolific and completed many significant public/private projects, as well as motion-picture set designs for MGM and Universal.6

Lovins had a flair for the dramatic, even by Hollywood standards. The 1927 opening of his new studio in Hollywood was described by art critic Margaret Craig as “genuinely cosmopolitan.”7 It was attended by the Consul of Guatemala and Southwest Museum founder Charles Fletcher Lummis, and Xavier Cugat performed. Craig wrote that it “could have been staged in South America or inspired a tale of Arabian Nights.” With a passion for music and theater, he hosted famous weekly soirees where opera singers, dancers, and musicians would perform in front of his hand-painted backdrops and huge parchment lanterns depicting Navajo, Hopi, Aztec, Toltec, Peruvian and Mayan motifs.8

As an educator, Lovins developed curriculum for many Southern Californian art programs, heading up art departments at the Los Angeles School of Art and Design, the San Diego Academy of Fine Arts, and preparatory schools including Holmby, Westlake, Marlborough, and Cumnock. He taught adult evening classes at Hollywood High and the Frank Wiggins Trade School (now L.A. Trade Tech), where he shared his knowledge for designing various revival-style interiors based on ancient civilizations and cultures. His student Lula Packer was captivated and immediately forged a connection with her then-married instructor. After an extended courtship, the couple married in 1930 with a reception at the Ambassador Hotel’s Mona Lisa Café. On their wedding day, Lula took on a new “artistic” name—Mona Lue Lovins—given by her husband.

Mona Lue and Henry Lovins, c. 1949. Photograph taken along Highland Avenue, near their estate, photo: Leland Auslender.

Mona Lue (1905–2000) was born in Fielding, Utah, and worked as an artist, educator, costume designer, and sculptor. She was raised in a conservative Mormon family that discouraged her intellectual and artistic pursuits. Still, she went on to study art at the University of Utah and Utah State University with artists including A.B. Wright and Calvin Fletcher and completed her post-graduate work under artist Lee Randolph at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco.

Upon arriving in Los Angeles, the quick-witted, raven-haired beauty supported herself as an au pair in Beverly Hills while practicing her art. Her family greatly disapproved of her marriage to Henry, a twice-divorced Jewish man twenty-five years her senior, and the union caused great controversy amongst her family and religious leaders in Utah. But in Los Angeles, free from those familial and religious constraints, she pursued her art and provided the stable partnership Henry needed in order to grow and expand the school.9

The Hollywood Art Center School offered a three-year intensive certificate program with majors in Fine Arts, Commercial Art and Illustration, Interior Decoration, Costume Design and Fashion Illustration, Cartooning and Animation, and Ceramics and Modeling. Students wishing to develop further abilities in Stage and Motion Picture Set Design, or Photography and Motion Picture Arts, could pursue a fourth year of study. The students went on sketching tours to museums and local points of interest, like beach and park areas, and conducted fieldwork and research at libraries and galleries to supplement their on-campus activities. In the spirit of Robert Henri, they were encouraged to pursue individual expression rather than imitate masters or adhere to established styles and arts movements.

Students working at the Hollywood Art Center School, c. 1960

By the 1940s, the school was thriving, operating out of three buildings simultaneously. It expanded to occupy the Wilshire Art Building at 3819 Wilshire Blvd and then 1905 N. Highland Avenue, which the couple purchased from Douglas Fairbanks Sr. That site featured a large Craftsman-style home that contained a classroom and studios. In the back, there was a staircase leading up to the house Frank Lloyd Wright designed for their neighbors, the Freemans. The Freemans were known for their salon-style events with noteworthy artists, architects, dancers, and filmmakers of the day.

1905 N. Highland Avenue

The last property Henry and Mona Lue purchased was at 2025 N. Highland, and it served as their final home, located just up the street from the Craftsman. At 2025 N. Highland, they built lush gardens all around the estate, believing gardens were as essential as the curriculum in creating an atmosphere that would ignite the artists’ imagination and open up new channels of visual experience.

The Hollywood Art Center School’s noteworthy faculty included Icelandic sculptor Nina Sæmundsson, California plein-air painter Jean Mannheim, watercolor artist and writer Estelle Ishigo, artist, poet, and publisher Ferdinand Penny Earle, and California plein-air painter Edward Langley. Its location in the heart of Hollywood provided the opportunity for faculty and students to work on varied projects such as the USC Tommy Trojan mascot sculpture (1930), the famous memorial to Italian actor Rudolph Valentino in Hollywood’s De Long Pre Park (1930), and the animation for Walt Disney’s Fantasia (1940).10

Student exhibition at Hollywood Art Center School, 1949, photo by A.L. Auslender

After Henry’s death in 1960, Mona Lue served as the school’s final director for nearly forty years. Mona Lue’s only child, Jay, assisted in managing the estate until his death in 1985. By then, the school’s profile in the local art community had begun to wane and, for various reasons, its official accreditation was not renewed. Still, the school stayed true to its early vision and continued to operate under Mona Lue’s direction until her own death in 2000. Devoted to her small group of students, she contended with financial hardship due to under enrollment and later fell victim to poor financial advice and exploitation by her estate lawyer.

Without Henry and Mona Lue, the school could never be what it was. But the estate and its contents tell the story of this forgotten school and its influence on the local art scene. Unable to evolve with the times as other early schools like Chouinard (now CalArts) and Otis were able to do, its demise allows the school to continue to exist, in a sense, as a preserved remnant of this potent creative period in Southern California.