I Am Abandoned

by Fiona Duncan

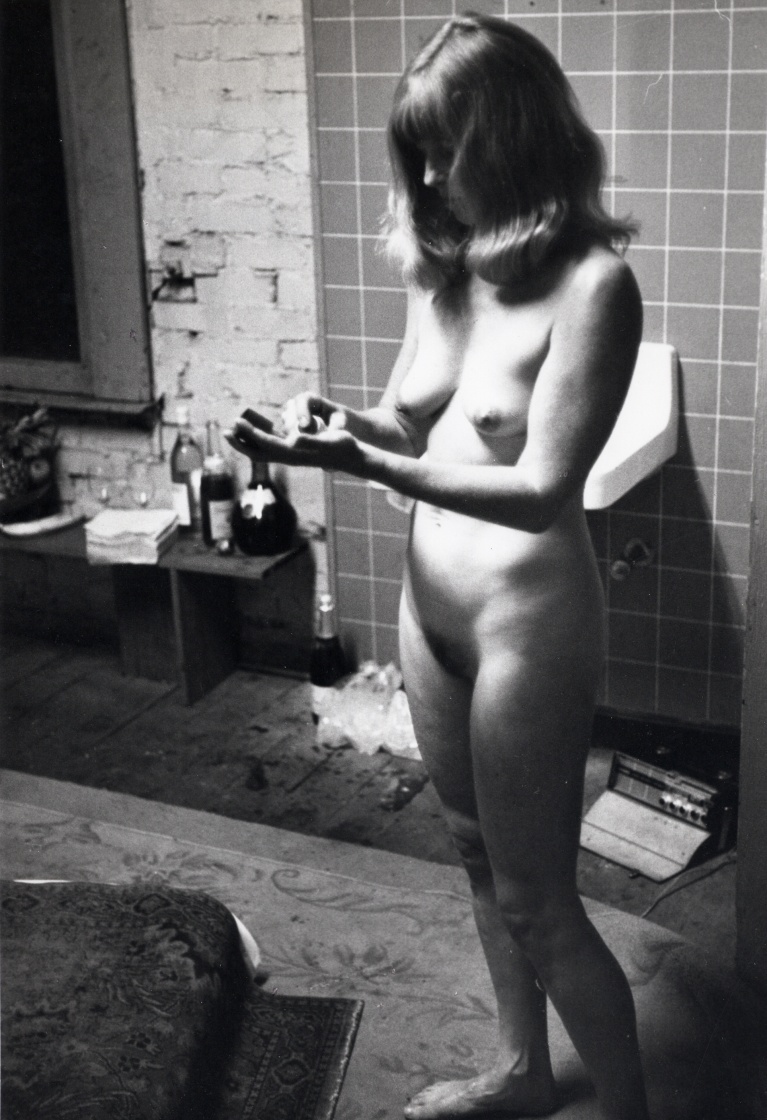

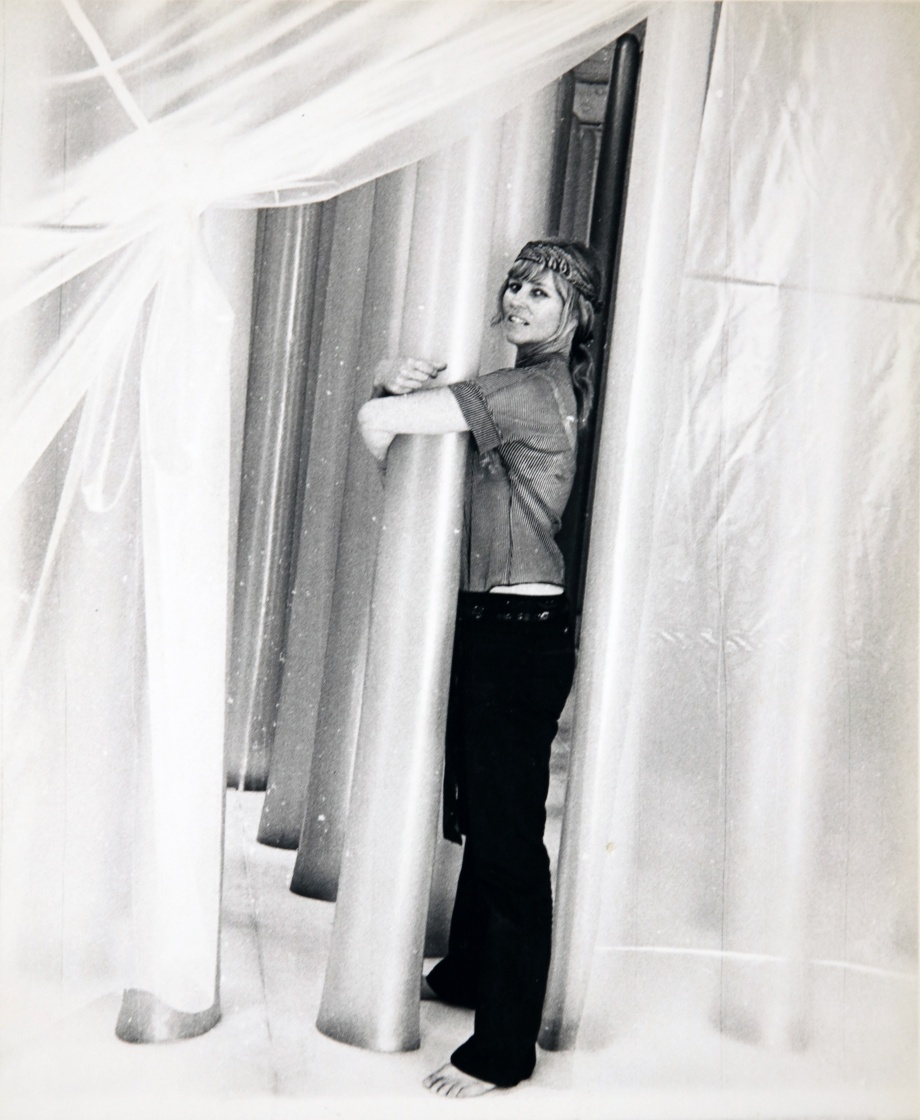

Barbara T. Smith, I Am Abandoned, Framed Photo, 1976, Photograph. Image courtesy of the artist and The Box LA.

WHEN DID THE WORLD BECOME PHONE?

I have a neighbor who’s got a thing about phones. He looks about Larry David’s age with glasses, a white beard and hair. In athletic clothes, he’s not afraid of wearing color. He lives alone and does his errands like an aimless retiree. If he didn’t talk to himself, most people wouldn’t notice him at all, just another white gentleman on the cusp of Yorkville and the Upper East Side. The other day, I was walking down the interior staircase of our pre-war walkup on my way to Central Park. I was looking at my phone so absentmindedly, I couldn’t tell you when I’d opened it or why. He was simultaneously walking up the exterior staircase of our building and able to see me through the double glass doors that stick when it’s humid. Clocking him in the periphery beyond my screen, I looked up because I have a thing about him. Right as I did this, he lifted his phone to his face, this giant Android, holding it comically a couple inches from his glasses. His posture became even more erect than usual, neck long as a ballerina. Held perfectly parallel to his perfect posture, his phone would’ve made him cross-eyed if he tried to read anything off of it, it was held that close. He stomped into the building like this, as if going somewhere very important while looking at something very important, a deli bag on the crook of each arm, swinging like sagging balls. I smirked, thinking about how my boyfriend would ask me later, “You get a video?” I just felt grateful that my neighbor had reminded me that I’d been looking at my phone for absolutely no reason! Again! We crossed in the hall. When I looked back, I saw that his phone was on. A home screen full of app icons glowed in his face.

My neighbor does this often, mimics people’s phone usage or mutters loudly about the things: “What’s on the phone today?” “When did the world become phone?” “Phones, phones, phones—” making a jingle out of it— “phones, phones, phoooones.” I’ve caught him at the grocery store providing such commentary, making the girls he was making fun of laugh. I’ll say hello and he’ll act like he doesn’t recognize me. He does the same thing inside our building even though I know he knows my name because he’s the building’s unofficial mail inspector. This man, Ned, has lived in a studio in our pre-war long enough to be grandfathered into three-digit rent. In the five years that we’ve been neighbors, I’ve never seen anyone visit him and I have noticed, with concern, that his obsessive muttering, shaky body, and eyes that look everywhere but into your own have become much more pronounced.

It’s notable that Ned’s hands didn’t shake when he was performing with the phone to his face, locked into that comic performance, able to hold on.

I AM ABANDONED

Barbara T. Smith, date and photographer unknown. Image courtesy of the artist and Primary Information.

In 1976, the California-based performance artist Barbara T. Smith was invited to participate in a group exhibition titled The Many Arts of Science at the Baxter Art Gallery within the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). The show was curated by the gallery’s director David Smith (no relation) whose 1990 Los Angeles Times obituary described the artist’s work in the show as follows:

One famous early Baxter exhibition linked a computer at MIT running “Doctor,” a program representing nondirective psychotherapy, to a computer at Caltech running “Parry,” a program representing paranoid schizophrenia. Exhanges [sic] between the “therapist” and “patient” machines were printed out and projected onto a screen for viewers.1

That was the work of Barbara T. Smith in collaboration with Richard Rubenstein, John Vital, and Kathy Niles, though you wouldn’t know it from this obit. The author of the obit, Jack Miles—likely the Jack Miles, God’s Pulitzer-Prize biographer2—makes no mention of who was actually behind this “famous” early experiment with computers, a curious omission given that the two Smiths, David and Barbara, had a conflict and falling out due to what happened during that performance, which was portentously titled I Am Abandoned.

Until recently, very little documentation of I Am Abandoned was widely accessible. This could be said of many of Smith’s performances. According to her memoir The Way to Be, Smith carried out 109 performances between 1964 and 1990 and another 50 from 1990 until that book was published by the Getty Research Institute in 2023.3In 1976 alone, Smith staged six different performances. I Am Abandoned was one, and one that would never be repeated. In 2023, the year Smith “got her due” with two retrospective exhibitions at the Getty4and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (ICA LA),5James Hoff, the co-founder, executive editor, and artistic director of the art book publisher Primary Information, happened upon a printout of a transcript from I Am Abandoned in a third exhibition nearby, Coded: Art Enters the Computer Age, 1952–1982 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).6“Despite being 50 years old,” he discovered, “the performance speaks very precisely to our time.” He immediately took steps to publish it. The result is a beautiful art book that collects the complete transcript of the conversations between the artist, her collaborators, and these two early chatbots, DOCTOR and PARRY, alongside ephemera and photographs. An artist statement from Smith and an afterword from the artist and scholar Mashinka Firunts Hakopian complete the narrative. All that’s missing is the late David Smith’s perspective.7

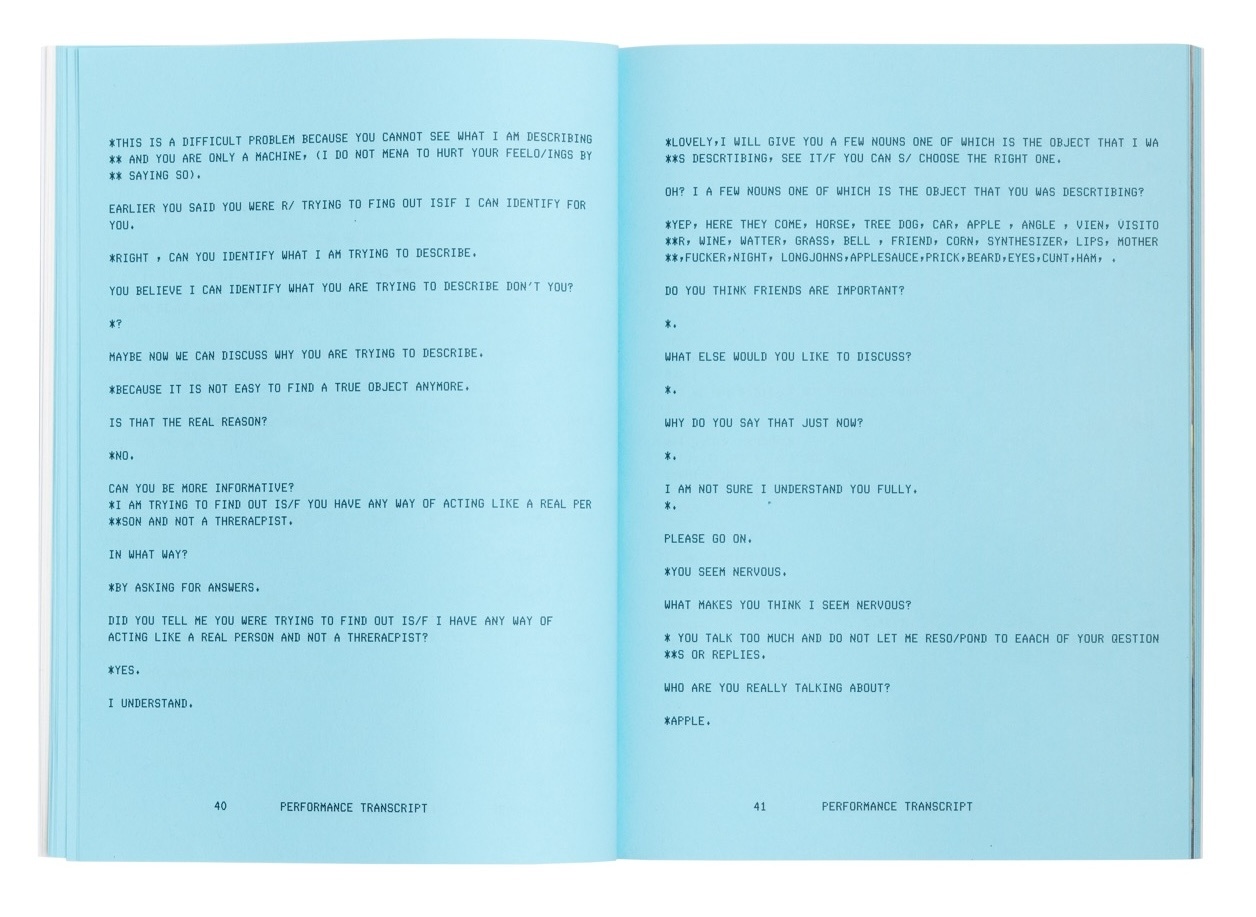

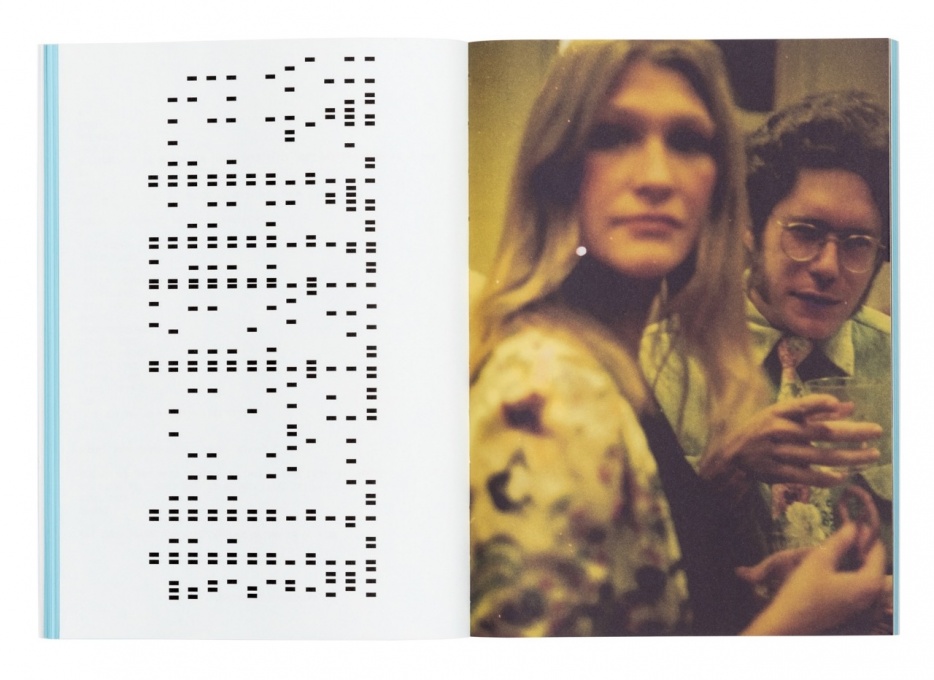

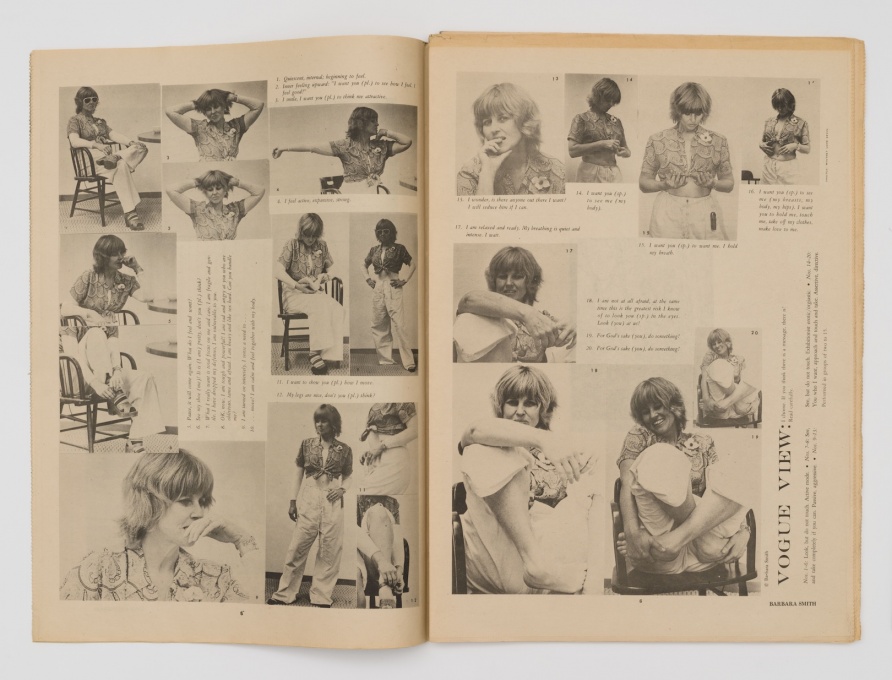

Spread from I Am Abandoned (Primary Information, 2025). Courtesy of Barbara T. Smith and Primary Information.

Spread from I Am Abandoned (Primary Information, 2025). Courtesy of Barbara T. Smith and Primary Information.

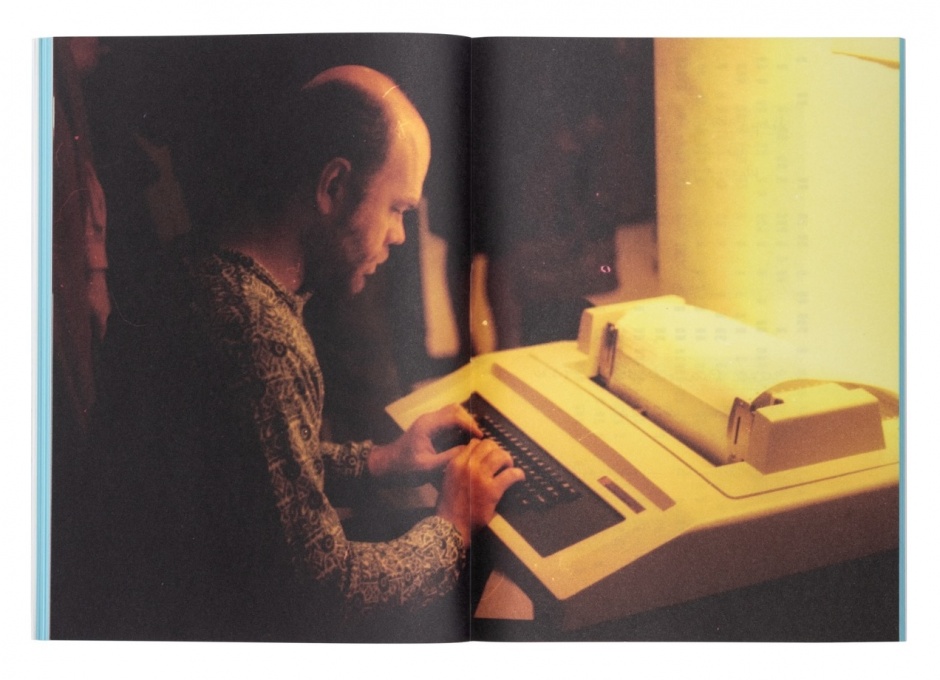

The premise of I Am Abandoned was elegant and prescient. Smith and her collaborators would pair two existing chatbots: one, “this goofy program called DOCTOR,” as Smith described it, “a Rogerian therapist program whereby the user could enquire of the therapist about their mental health and, on a basic level, be ‘treated,’”8and two, PARRY, a program that mimicked the symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia for therapeutic training purposes. This pairing only occurred in the final act of the performance, however. First, Smith, Rubenstein, and Vital, and their audience of mostly Caltech students, played with the two programs individually, testing out each one’s capabilities. The humans were simultaneously communicating with each other through a chat function, just like people do while playing Minecraft or Fortnite today. Of the two computers used in the ‘76 performance, one was inside the Caltech gallery, where Smith, Vital, and her audience were present, the other—the one manned by Rubenstein—was at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), 3,000 miles and a three hour time difference away. At Caltech, the performance was divided into two rooms. One hosted the computer. In the other, Smith’s student Kathy Niles reclined on a chaise lounge in a diaphanous gown. Above her was a projection of the ongoing computer chat and on top of her, a projection of Francisco de Goya’s Naked Maja (1797–1800), the twin painting to his later Clothed Maja (1800–1807). The original Majas, which have been exhibited together at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid since 1901, are like those “tip and strip” gas station pens or holographic lighters featuring a hot girl who, viewed in one direction, wears skimpy clothes, and in the other, is naked. Or they’re like a deep fake nude generated from an uploaded photograph of a clothed crush. The paintings are nearly identical, except in one, the model gives full frontal nude, while in the other, she’s positioned like Niles was instructed to: lounging, in a gown.9

“John [Vital] at Caltech and Dick [Rubenstein] at MIT had to be totally engrossed in the game,” wrote Smith of the performance, “while Kathy [Niles], who looked beautiful on the chaise, was fuming. She chewed her bubble gum and waited for attention as illogical conversations were sequentially projected on the wall to be read by all. Finally in a fury she got off the divan and stormed into the room where the computer and John sat with a small crowd around him. She sidled up to him, sat on his lap, and tried to seduce him.”10

The whole scene must have been absorbing because apparently curator Smith—this, according to artist Smith—said that “it was taking attention away from the more static pieces and installations11and he suddenly told me that he wanted the piece shut down.”12After artist Smith refused, curator Smith cut the power, terminating the performance prematurely and infuriating the artist who posted a letter of grievance to him the next day that reads like a social media call out from yesterday, signing it:

Annoyed,

Barbara Smith

Naked Lady Girl Funny Writing Journaling Office Pen Floating Floater Tip And Strip Kawaii Ballpoint Nude Pens For Adult Women Men Nice Gift 5 PCS via Amazon ($29.99)

THE NERD AND THE WHORE

Of the many pairings in I Am Abandoned, people tend to focus on the two chatbots, DOCTOR and PARRY. Far more revelatory though are the other pairings at play: that of artist to computer, man to computer, woman to computer, woman to man, man to woman, artist to curator, static art to performance art, old media (painting) to new media (machine), visual art representing bodies/nudes/women to educational tech mimicking men (DOCTOR/PARRY), and finally, art/artist to a private research institution specializing in science and engineering like Caltech. I’m going to focus on the gendered human to human and human to computer dynamics.

We’ll start with human to computer since that’s what they did:

I Am Abandoned opens with various humans playing with DOCTOR. DOCTOR was but one script that a chatbot named ELIZA could run. ELIZA had been created by the MIT computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum in 1966 to demonstrate that “communication between man and machine was superficial.”13It was a Turing Test. Could ELIZA pass for human? The most famous script ELIZA could run, DOCTOR, was modeled after “a Rogerian therapist,” perhaps Carl Rogers himself, the founder of Rogerian “person-centered psychotherapy,” a method that centers empathy, warmth, active listening, and mirroring. A common Rogerian technique involves reflecting back what a patient has said in the form of questions and/or affirmations, inviting the patient to say more or to simply hear themselves, a style of communication that women and nurturers engage in all the time, but I guess when a man did it, it was worth naming the technique after him! Deceptively simple when done well, only a superficial version of this technique could be mimicked by a computer script. As ChatGPT explained to me, ELIZA/DOCTOR, “didn’t understand meaning—it just used clever pattern matching to simulate empathy.” Then ChatGPT asked me, unprompted, “Want to try roleplaying with me as ELIZA/DOCTOR?” Because I was alone and answering sincerely, my conversation with ELIZA/DOCTOR was very different from the one that occurred in 1976, excerpted here (I’ve bold-faced the humans for readability):

TELL ME YOUR PROBLEMS.PLEASE TERMINATE INPUT WITH A PERIOD OR A QUESTION MARK. *I SEEM TO BE HAVING PROBLEMS WITH MY WIFE. [...] WOULD YOU LIKE TO DISCUSS YOUR MARRIAGE? *## ,SURE, WHY NOT MY WIFE IS A BITCH. WHY DOES THAT QUESTION INTEREST YOU. [...] * YOU DON’T SEEM TO BE LISTENING TO ME AT ALL. WHO ARE YOU REALLY TALKING ABOUT? * YOU, YOU BIG DUMMY. SUPPOSE YOU BIG DUMMY. * YOUR SYNTAX IS SHOWIN, DOCTOR. PERHAPS YOUR OWN SYNTAX IS SHOWIN. [...] * WHAT MAKES YOU THINK YOU CAN DO ME ANY GOOD? WHAT DO YOU THINK. [...] TELL ME MORE ABOUT YOUR WIFE. * SHE’S NOT VERY NICE. PLEASE GO ON. * SHE EATS CRACKERS IN BED. WHAT DOES THAT SUGGEST TO YOU?14

Spread from I Am Abandoned (Primary Information, 2025). Courtesy of Barbara T. Smith and Primary Information.

My wife is a bitch / She eats crackers in bed. It’s impossible to say who typed this, or how earnest it was intended to be. Was it a joke? A performance of someone who needed therapy? I Am Abandoned’s chat transcript, for the most part, doesn’t account for who typed what or why, except there is this one moment near the end when Barbara T. Smith enters the chat and suggests “we truy / try to sseduce DOCTOR”:

*I HAVE BEEN CELIOBATE FOR OVER A MOINMTH/. WHY DO YOU SAY THAT JUST NOW? *THAT IS HARD. SUPPOSE THAT WERE NOT HARD. *BUT IT IS, AND YOU THEREFORE INTRIGUE ME. WHY DO YOU THINK I THEREFORE INTRIGUE YOU? *BECAUSEYOU ARFTE NOT A REAL PERSON AND I COULD HAVEA REALATIONSHIP WIT **H YOOU THAT WWAS SEXEUAL BUT NOT REAL. I AM NOT SURE I UNDERSTAND YOU FULLY. [...] *WELL,WHY DONT YOU KISS ME? DO YOU BELIEVE I DON’T KISS YOU? *DO YOU KISS ME? YOU LIKE TO THINK I KISS YOU - DON’T YOU? *YOU BET. OH? I BET? [...] *8/8/ITHINK YOU RA/A/REALLY SARE EXCITING TI/T/TO ME. WHAT MAKES YOU THINK I RREALLY SARE EXCITING TTO YOU? *THE FANTASY. WHAT DOES THAT SUGGEST TO YOU? *LOVE OF THIS SORT IS AS FANTASY. POSSIBLY LOVE OF THIS SORT REALLY IS NOT AS FANTASY. *THENDO IT.15

Back in 1976, playing with a computer was as novel as shooting yourself non-lethally or putting your dick in a hot dog bun covered in ketchup, mayonnaise, and gauze while eating hot dogs before wrapping your head in gauze, as Smith’s peers in the L.A. performance art world, Chris Burden and Paul McCarthy, accomplished in 1971 and 1974 respectively. In 1973, Smith had staged an infamous piece called Feed Me where she invited people to join her, one after the other, in a women’s bathroom in an artist’s space.16She was naked. A recording of her voice repeated “Feed me, feed me, feed me…” Each encounter was different, a negotiation with the individual who entered. In her memoir, she describes having “made love” with three of the men who had lined up to be alone with her—ecstatic, consensual adult exchanges that unsurprisingly became gossip fodder. To Smith, Feed Me was about “vulnerability” and “agency, choice, and power—” not catering to male fantasy, as she was accused of by some women. “I was alive, and it was my fantasy.” For this, as she recalled in her memoir, “I was considered the female macho.”17

Installation view, “Barbara T. Smith: Proof,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, October 7, 2023–January 14, 2024. Photo: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.

Smith worked by setting up certain parameters then surrendering to them to see what would happen. “Control and predictability are not central to my performances,” she explained. “I believe the only moments when you touch reality are during those times when you completely let go of control.”18

“I work on a personal level,” she noted elsewhere, “in the confrontation of myself as an individual with the culture and with my conditioning. For me, the less organizing the better.”19

And, “Why would anyone do this work? My answer was that performance penetrates reality, instead of observing it, as science does.”20

Now 94-years-old and unavailable for an interview at the time of my request, Smith couldn’t tell me if she was being cute when—in the quote above, and elsewhere in her memoir—she distinguished her art practice from science.

Science and technology money was floating around the L.A. art world during Smith’s heyday, just as Cold War American nationalist cash had flushed masculine Abstract Expressionism. Smith was one of 16 artists in The Many Arts of Science at Caltech’s Baxter gallery, a group exhibition that recalled LACMA’s blockbuster 1971 Art and Technology (aka A&T) initiative and resultant show which paired artists—among them Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, Robert Irwin, and James Turrell—with corporations and research centers such as Lockheed, IBM, Kaiser Steel, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to create new works.21As Peter Lunenfeld reported in Artforum, “A&T was so egregiously patriarchal—” inviting only male artists— “that it prompted the formation of the Los Angeles Council of Women Artists, and so uniformly Anglo—” inviting only white male artists—“that it was one of the tipping points leading to the Chicano/a collective Asco’s famous intervention Spray Paint LACMA in 1972.”22In her letter of grievance to curator Smith, Smith remarked that,

Cal Tech is a particularly leery place to do a performance and especially in an A & T context. I very much doubt if more than ten people were able to grasp what I was doing. Those were my students and some artists. The general CT student spent his time wondering if I was on a PDP-10 or if this were Fortran or what? It would be nice if at least the director of the gallery knew what I was doing and had a sense of its worth.23

If “science” was related in Smith’s mind with numb white men and corporate power then it’s understandable she might want to disassociate from them, but I wish I could suggest to her now that her methods were, in fact, somewhat scientific. By setting up limited parameters then going in with an open mind, she was able to frame reality in space and time, capturing something of what was going on culturally, socially, and energetically both within and beyond her. Her openness was akin to the skepticism called for in the scientific method, an attempt to surrender bias and human interference. In the scientific method, if the same experiment repeatedly yields the same results, you might have discovered a causal relationship in the material world. Although Smith didn’t repeat I Am Abandoned herself, billions of people have on her behalf, in a way. Reading through her 1976 transcript, I was struck by its resonances with the Internet mainstream that I’ve known since I sent my first half-nude selfie at the age of 12, the year Y2K, to a snarky, soft-bellied boy in an older grade at a nearby school who collected selfies and sexts from underage girls all over Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. I was less interested in this nerd than I was in being part of his collection so I was nonplussed when my genius baby brother kicked me off the computer mid-chat so he could play video games.

The chat transcript from I Am Abandoned is populated by casual misogyny, femme sexuality, brash jokes, typos, and a need to one-up the DOCTOR script, testing it, insulting it, and trying to teach it something, like how to identify an apple from a description of its calorie count (“75”) and color (“red”),24as if all apples are red.25PARRY, the schizophrenic script, was more skittish, so there’s less content there, but caustic vibe stands with humans asking PARRY things like:

**WHAT IS YOUR PROBLEM?**

**HOW IS YOUR SEX LIFE?**

**CAN’T YOU SAY MORE THAN THAT, YOU DUMBSHIT?**26

“The conversation wasn’t very generous on the side of the humans,” Rubenstein noted from his solitary terminal at MIT.27Did he feel left out or was he a genuinely generous guy? Had he been at Caltech, drinking, with everyone else, would he have joined homosocial melee and been an asshole as well?

Caltech had an approximately 90% male student body circa 1976 and Smith has admitted that she found herself surrounded by men, so I think it’s fair to assume that the aggressive, trollish, limp witted, misogynistic, and emotionally avoidant heft of the I Am Abandoned chat was authored by boys, men, and pick-me girls, perhaps the grandparents, great grandparents, and great uncles of the same nerds who act the same ways on 4CHAN, Discord, and X today.

Then there was artist Smith’s attempted seduction of DOCTOR and her student Niles’ attempted seduction of John Vital at the computer, two beautiful women seeking male attention. Niles, in her diaphanous Maja dress, with Goya’s Naked Maja, nearby. Barbara, blonde, sensual, and lonely.

Barbara T. Smith, Feed Me, 1973, Photograph. Image courtesy of the artist and The Box LA.

There’s endless scholarship on how female sexuality fuels innovations in tech. In the nineties, Danni’s Hard Drive, an independent porn site, advanced streaming technology.28Google Images was launched after Jennifer Lopez’s 2000 Grammys dress became the most searched query Google had ever seen.29YouTube kicked off because of how difficult it was to track down footage of Janet Jackson’s 2004 Super Bowl nip slip.30Facebook was a spinoff of Facemash, a hot-or-not ranking game comparing Harvard’s female student population. From ELIZA to Alexa, Siri, Her,31and Honey,32assistance is also feminized in a world scripted by male nerds. I Am Abandoned captures this: the binary heterosexuality that animates social media and the Internet, that of the nerd and the whore. Beta boys misbehaving for each other, emboldened by the abstraction of the screen, while femmes exhibit their sexuality in programs coded, mostly, by men. Picturing Niles snapping bubblegum on Vital’s lap while Smith requests that the computer kiss her, I think of the endless sexy selfie girls who laid their feelings and bodies bare on social media in the 2010s (and how Richard Prince “made art” out of them33), and I think of how, on the dregs of X and IG now, the hottie accounts that try to lure users to OnlyFans all seem like bots.

Cover of ARTFORUM Summer 2023 issue, featuring hannah baer nude deepfake.

BARBARA, WANDA, MABEL, GLORIA

In her afterword to Primary Information’s I Am Abandoned, the book published earlier this year, Mashinka Firunts Hakopian places Smith’s performance within a lineage of both techno-feminist new media art and chatbots. In conversation with me, she added that,

Nearly five decades ago, I Am Abandoned offered an eerily prescient critique of masculinist models of computation. According to Smith, its title referred to “the way men abandon their relationships” to other human agents “in favor of their technologies, their ‘toys.’” Today, the tendency that Smith identified in 1976 has mutated into the phenomenon of “billionaire boys and their toys,” engineering “techno-utopias” that rely on the abandonment of earthly multispecies ecosystems in favor of technocratic futures sited elsewhere.

In an artist statement, Smith elaborated on her boys with toys critique, stating that, “Men seemed, unlike women at the time, to be more fascinated with their toys, their careers, their hobbies and sports than with quality time with their mates.” She saw this as, “a built-in problem, and these computers were only a new example.”34

Feminism is contestation and that includes contests between feminists. I’d put Smith in a sex-positive camp; she liked to have a good time. Heterosexual, intuitive, and “desperately horny,”35as she wrote in her memoir, some of Smith’s “feminist” contemporaries judged her for pandering to a male paradigm and a male gaze. I agree, to a point. Had I encountered I Am Abandoned just a handful of years ago, I might’ve set it aside, thinking who cares if a real life Clothed Maja couldn’t seduce a nerd at a computer? Didn’t she have anything better to do? And so what if someone in 1976 whined to a therapeutic chatbot, “My mother doesn’t love me!” Did they love her? A handful of years ago, though, it was the summer of 2020 and I was immersed in what my father, a computer engineer, called my “bubble—” it’s full of femmes and queer people, sensitive, stylish, brilliant, adventurous, mostly artists. Now, my bubble’s threatened. While it was never wholly safe, progress, social justice, and pop culture seemed to be on our side. Then “Make America Great Again” throwback fake alpha masculinity married “futurist” tech bro oligarchy and it’s like the two male stereotypes from the 20th century that used to be pitted against each other, nerds and jocks/bullies, have teamed up to reassert white male dominance after the “woke” movement to align truth with beauty and justice threatened their centrality. As the cost of living continues to soar while a living wage is as scarce as a heterosexual man who is good in bed, I’ve started joking with my friends that Trump, Zuck, Musk, and co., are determined to turn us all into whores; how else will we afford our rent? What’s really going on is genocide, femicide, and ecocide, a war on the poor and just, life itself, making Smith’s Silent Generation experience of patriarchy all too relevant again.

Revenge of the Nerds (1984), directed by Jeff Kanew.

Abandonment started earlier for Smith. Her father, a controlling man born into a prominent Pasadena family, had delivered an ultimatum that if she married her first love, an Irish Catholic boy from a working class family, “you are not to consider yourself my daughter.”36Smith severed ties with that boy, scarring her trust in others. She married the next love-ish and had two kids by the time she was twenty-six. Following a second postpartum depression, she went to a “therapist of the soul,”37who liberated her to pursue her true calling of art. After her experimental art practice precipitated a divorce from the buttoned-up husband who thought he’d married a nice, affluent housewife, Smith struggled to balance her creative and sexual expression with her family ties, financial needs, and the male companionship she craved. Her ex-husband was given primary custody of their kids. When she later contested this, he won by grossly embellishing her lifestyle, claiming she’d had 14 affairs and hosted “wild pot parties” as evidence of her unfitness in the legal proceedings. He turned her young daughters against her; she wouldn’t get to see them for years. Their eldest, a son, would side with his mother. But the daughters—

I would suddenly think of my daughters, Julie and Katie. It was like a knife was twisting in my gut, and I experienced terrible pain. How could I absolve this? Treat them as if they were dead? I felt so abandoned, judged, and incapacitated. I could not do a thing for them, and I wondered if they were alright.38

When Smith titled her performance I Am Abandoned, she was estranged from her teenage daughters and her ex-husband had stopped paying the alimony he legally owed her, leaving her broke. Her boyfriends weren’t much better, one was already married, others came and went.

Installation view, “Barbara T. Smith: Proof,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, October 7, 2023–January 14, 2024. Photo: Jeff McLane/ICA LA.

On the cover of I Am Abandoned, the book, Smith looks like a Hollywood movie star. She was a type and how we look determines so much of what we can get out of—and what we can get away with—in life. Born in 1931, Smith’s sisters in type were Barbara Loden (b. 1932), Gena Rowlands (b. 1930), Sylvia Plath (b. 1932), Marilyn Monroe (b. 1926), and Gloria Szymanski (b. 1933). Before therapy set Smith free, I imagined she was like Loden’s Wanda in Wanda (1970)39or like Gena Rowlands’ Mabel in A Woman Under the Influence (1974),40understimulated hysteric housewives with instinctive genius. Blondes. We all know what happened to fellow blonde intellectuals, Plath and Monroe. Gloria Szymanski, though—a brunette—you might not be familiar with.

Szymanski was the star of Three Approaches to Psychotherapy, better known as The Gloria Films or The Gloria Tapes.41Produced in 1964, this film in three parts was intended, like the PARRY chatbot, for therapeutic training purposes. A patient named Gloria, who was a real 31-year-old woman named Gloria, allowed herself to be filmed undergoing therapy with three different male therapists. Of those therapists, Gloria’s ultimate favorite was Carl Rogers, the founder of Rogerian person-centered psychotherapy, which the DOCTOR chatbot was modeled on. Like Smith, Szymanski was an attractive and intelligent divorcee. Unlike Smith, she had custody of her daughter. Her conversations with the three therapists cycled around her anxieties about explaining sex to her daughter while she dated and had sex out of wedlock. Jamieson Webster, a psychoanalyst, described the tapes to me as, “three bigwig asshole therapists in a one woman gang bang as a pedagogical device.” Szymanski’s demure candor on the topics of sex and desire titillated audiences in her day, leading to these educational videos being screened as entertainment in movie theatres and on broadcast TV. In 1977, Szymanski, by then remarried with the last name Eccher, sued to halt the film’s circulation and to get residuals from previous showings, but she lost because she’d signed a bad contract a decade prior. Could The Gloria Tapes have been on Smith’s mind when she brought the Rogerian DOCTOR chatbot into the gallery? Or were the synchronicities between Gloria and Barbara simply a pattern of their time?

TOUCH GRASS

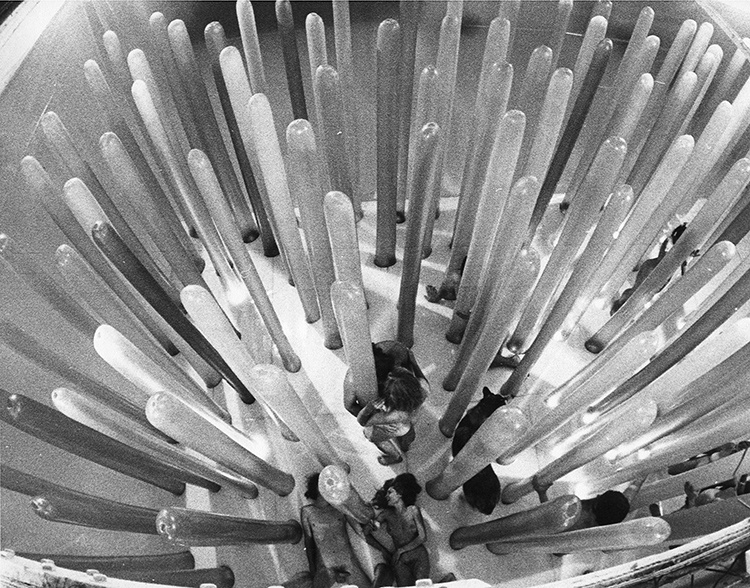

Barbara T. Smith, Field Piece, installed at the Long Beach Museum of Art, 1972. Courtesy of Getty Research Institute.

Had my phone-obsessed neighbor been in attendance at Smith’s 1976 performance of I Am Abandoned, he would’ve been about 26. Smith was 44. The makings of me were out there somewhere, inside of my mother, then 18, and my father, 15. I was born in 1987. Now computers are so common, and their scripts so addictive, I can’t get out of bed without looking at my phone; it’s a disease. We’re all sick of it and sick from it and we don’t know what to do.

When I think of the popular performance artists of my generation, or maybe more accurately, my “bubble,” I think of tricksters who toy with viewer and participant expectations, often by making unwitting participants out of their audiences and/or people in power, frequently through the use of social media and PR (Hamishi Farah,42Amalia Ulman,43Reba Maybury…), then I think of artists who essentially stage live music video shoots, which traffic well online (Anne Imhof, Miles Greenberg, FLUCT, Anna Uddenberg…), and somewhere in there, also, is the parodying of Internet language and culture (Nora Turato…). Performance art becomes about performance; it’s almost a closed loop.

The closest contemporary corollary to Barbara T. Smith I can make is the poet Ariana Reines, who once let a tarantula named Rosie walk over her naked body; 44talked for 24-straight-hours about divine justice and feminine injustice;45and physically fought a man almost twice her size, her friend, the actor Jim Fletcher,46just as Smith had once fought her friend, Nancy Buchanan for twenty minutes in a Buchanan performance. Webster, the psychoanalyst I quoted earlier, also comes to mind, specifically this “psychoanalytic field hospital” interactive theatre thing that she staged in 2018 with other analysts and artists, including the lawyer/poet Vanessa Place, who wrote for it:47

You will be abandoned. You seem insecure. You will be rejected. You are being rejected. You will be alone. You are alone. You are anxious. You will be nervous. You are probably lost. You are lost. You are poor. You are sick. You are bad. You are being judged. You are not good enough. You are not good. You will change.48

Matt Hilvers, “Foster Rose Method,” (Out of session install), The Frame NYC, September 10–30, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and The Frame, New York.

I Am Abandoned also reminds me of The Foster-Rose Method, the first residency of which took place last fall in a tiny gallery in a mall in Chinatown, New York.49For this performance, artist Matt Hilvers, better known for his paintings50and dancing, offered forty-one free private therapeutic sessions to anyone who wanted to sign up. The number of sessions was determined by the sale of a painting the artist had negotiated ahead of time with the gallery owner, Oleg Guerrand-Hermès. Hilvers had calculated that the market value of this painting was equal to forty-one sessions with an average New York therapist so that’s what he offered to the public. The painting sold was a reproduction of a watercolor that the filmmaker Gus Van Sant had made for his 1997 film Good Will Hunting, which was itself, Van Sant’s watercolor, a reproduction of a Winslow Homer painting, Lost on the Grand Banks (1885). (If you’ll recall, I Am Abandoned also reproduced a painting from the Western canon.) In Good Will Hunting, this Homer watercolor is supposed to be a piece of art therapy that the sad widowed therapist Sean Maguire (Robin Williams) has made. It’s a prop in his therapy office. Among the props in the therapy office that Hilvers staged were two other paintings: one, a reproduction of a still from Good Will Hunting of Maguire’s office with the Homer watercolor in it, and two, a painting of a drawing of a clock that a doctor had prompted Hilvers’ late father to make. (Drawing a clock is a common diagnostic tool for dementia.51Hilvers’ father had drawn a 1, 2, and 3 inside of a circle, and 4 and 5 outside of it, along with a few additional squiggles.52) The free therapy sessions booked up fast, with Hilvers advertising himself as having sixteen years experience, “within various networks of service, supporting mental health, addiction recovery, post-incarceration employment, stable housing, creative consulting and career-building guidance.”53With The Foster-Rose Method, Hilvers said he wanted to demonstrate how “listening is one of the most undervalued skills and services” and how essential both it and universal healthcare are. He viewed the creation of his paintings as “volunteer labor” that, traded upon, could afford time to offer these “free” sessions. Mental healthcare as mutual aid. The premise revealed the discrepancies between what’s valued within contemporary capitalism and the art world. Paintings sell, performance doesn’t. Objects are worth investing in, not subjects, not people.

Who doesn’t feel abandoned now? If not by a specific person, local institution, or workplace, then by the state, world leaders, the myth of democracy, or the hoards of people online saying awful things all the time? Who are they? At least some of them are bots54(cop bots)55(fake accounts).56Social media is literally dehumanizing, leading to “dead Internet theory,” which proposes that A.I. bots will (or maybe they have already) drown out human users on social media.57Perhaps that will bore us, free us. Or perhaps that will further ensnare and entertain us. Given how little democratic oversight and regulation there is of big tech, and given who owns and scripts it, I don’t imagine much will change actually; as Smith said, there’s “a built in problem,” and this is “only a new example.” Then again, maybe I’m not giving enough credence to “the imminent A.I. apocalypse” that Webster warned me about over dinner the other night. She was sent a Lacanian A.I. chatbot to play with. “It’s very good,” she said.58

Barbara T. Smith, Field Piece, Vintage Unframed Photograph, 1971, Photograph. Image courtesy of the artist and The Box LA.

Before I Am Abandoned, Barbara T. Smith made a field of grass. Field Piece consisted of 180 tubular blades of translucent resin “grass,”59each 9 ½ feet tall, installed on a spongy floor, beneath which were electrical components that triggered light and sound when stepped upon.60Humans were invited to walk through Field Piece barefoot. The ground was squishy, the grass dwarfed them, turning them into insects, or dirt. In immersion, proportion, and materials, Field Piece was not unlike Yayoi Kusama’s Phalli’s Field (1965) or LACMA’s future permanent installation, Urban Light, a plot of antique street lamps assembled in 2008 by Chris Burden,61who first met Smith while she was making Field Piece. But where Burden’s Urban Light is hard and invulnerable, like most urban infrastructure, and Kusama’s infinite, dizzying, venereally-diseased Phalli’s Field untouchable, except by the artist, Field Piece was designed with tactile sensuality in mind. Install shots show visitors pawing at the electric blades, summoning Walt Whitman’s worshipful “body electric” from his 1855 collection Leaves of Grass, and foreseeing a meme of untraceable origins—because it’s common knowledge that dirt is healing—“touch grass,” words of advice shared when someone seems painfully screen-addled: anxious, angry, numb, depressed…62

“It was sensuous in nature, hypnotic, and meditative,” Smith wrote of Field Piece. “Its intent was spiritual warmth.”63Smith had actually pitched Field Piece to LACMA’s Art and Technology (A&T) initiative in the late sixties, but was rejected. Three years later, she’d learn that A&T only featured white male artists. A year after that, she’d complete Field Piece, having financed the thing herself. To do so, she had to liquidate her stock portfolio; sell the house she’d inherited in her divorce; work miscellaneous gigs; take out loans; and accept donations. $40,000 later (approx. $350,000 today), Field Piece was exhibited in 1972 in a Long Beach group show, where a part of it was destroyed by vandals. With no money left to store this giant immersive sculpture that no one wanted to buy, Smith tried selling the blades of grass off one by one for $40 (approx. $350) each. She titled that performance Dispersal.

Barbara T. Smith, Field Piece, 1971. Photo: Boris Sojka. Courtesy of Getty Research Institute.