One for the Future

by Allison Noelle Conner

Cauleen Smith, Pilgrim, 2017, single-channel video (color, sound), 7.41 minutes (still). Courtesy of the artist and Corbett v. Dempsey.

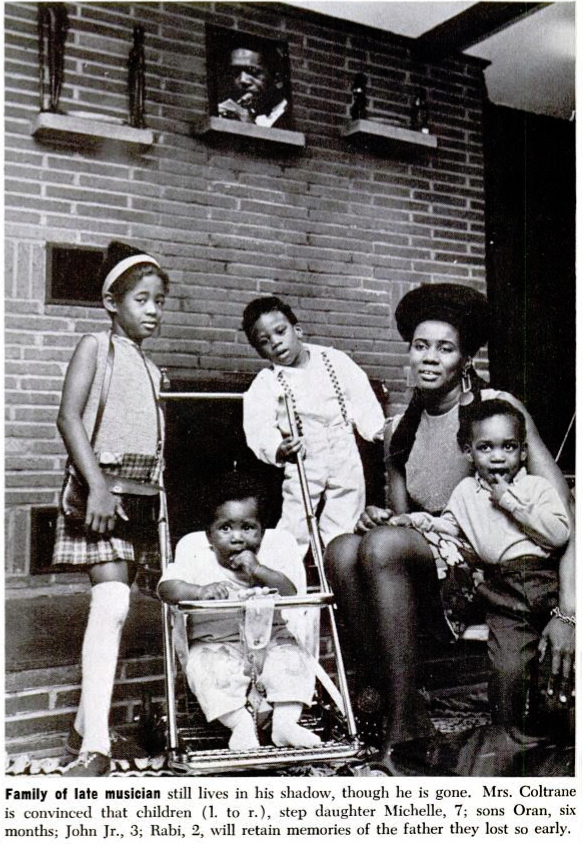

1967 was a bitter and destabilizing year for jazz musician Alice Coltrane. Her husband and collaborator, saxophonist and bandleader John Coltrane, passed away from liver cancer in July. His death rocked Alice to her core, unraveling the life they had built over the last four years. Music had drawn together their souls, and John’s music had become increasingly more experimental, informed by the couple’s spiritual explorations. (For John, music was a divine pursuit, a way of channeling the universal source of all things.)1 When he passed, Alice was 30 years old, with four children under ten to support. The circumstances seemed untenable, the systems that organized her life thus far—marriage, family, career—disappeared in a flash, as if eaten up by flames. Although she had experienced the end of a marriage before (she divorced her first husband in 1960), John’s passing overcame Alice like a psychic disaster. Britt Robson writes of her fractured state during the years 1968 to 1970:

Unable to sleep or eat properly, her weight fell from 118 to 95 pounds. She had hallucinations in which trees spoke, various beings existed on astral planes, and the sounds of “a planetary ether” could spin through her brain and knock her unconscious. Her family was concerned for her health, and more than once she was sent to the hospital due to self-inflicted wounds, including a third-degree burn so awful that her blackened flesh fell off her hand.2

Alice Coltrane and family in EBONY magazine, November 1967.

Looking back at this period in her 1977 memoir Monument Eternal, Alice understands these hellish trials as the beginning of her spiritual transformation.3 She underwent tapas, a Sanskirt term describing a period of unrelenting austerity and penance, where the body endures “extreme forms of physical pain, suffering, and torture.”4 These rituals of self-discipline and mortification were seen as necessary for her own ascension, offerings that proved her devotion while preparing her flesh for a path unshackled from earthly distractions. She writes in Monument Eternal: “A human who is going through austerity aspects of spiritual revelation must be able to withstand the effects of purification, which is analogous to the processes and the results of empirical chemistry performed by the alchemist who transmutes base metal into gold.”5 For Alice, tapas was akin to alchemy, a process in which a person can reshape and remold.

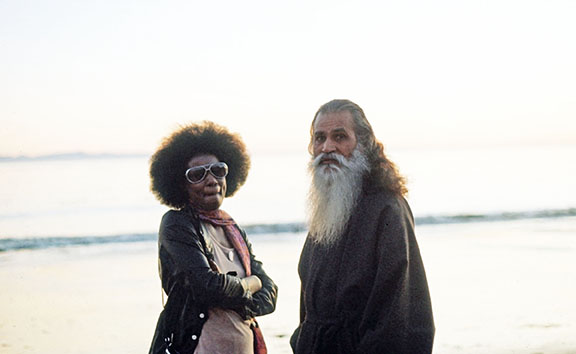

In 1969, Alice met Swami Satchidananda, an Indian guru and yoga teacher who had gained a sizable following in the U.S. (he performed at the Woodstock Festival that same year). Satchidananda taught Advaita Vedanta, a school of Hindu philosophy in which the observable world is merely illusory, higher consciousness is seen as reality, and all existence is connected as one. Alice found Advaita Vedanta to be freeing, a way of breaking from stagnate systems of being that confined her both spiritually and creatively. Franya J. Berkman, author of Monument Eternal: The Music of Alice Coltrane, provides another reason for Alice’s deep connection with the Vedic tradition: “In its inclusiveness and emphasis on personal potential, Vedanta is similar to the spiritual and creative philosophy that John Coltrane developed.”6

Alice Coltrane with Swami Satchidananda.

It was during this time that Alice’s own spiritual expansion would become her most vital creative muse, and would remain so until the end of her life. She released Journey in Satchidananda in 1970, about a month before she departed to India with the swami.7The album opens with a deep, aching hum, courtesy of the tamboura played by instrumentalist Tulsi Reynolds, announcing Alice’s new Eastern inflections. After her tapas, Alice began experiencing “supra-terrestrial abilities and a deep and direct connection with the Supreme Lord.”8 Her decision to play organ came out of one such divine vision. Upon her return from India, she released Universal Consciousness (1971),9notable for being the first album on which she plays the Wurlitzer, which would later become the centerpiece of her religious recordings.10In 1972, Alice and her children relocated to California, at first settling in San Francisco and establishing a Vedantic Center in her home. Four years later, Alice received another revelatory message that would lead her to the outskirts of Los Angeles. She had been divinely instructed to build an ashram. To mark her devotion, she took the name Turiyasangitananda (sometimes shortened to Turiya), Sanskrit for “the bliss of God’s highest song.”11

Turiya’s music and teachings appear throughout Give It or Leave It, artist Cauleen Smith’s 2021 solo exhibition at Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Anchored by her investigations into self-generated sanctuaries, experimental film, spiritual jazz, Afrofuturism, and Black feminist texts, Smith recovers past social experiments led by Black artists and radicals, staging renewed narratives that fuse her historical research with our contemporary, disaster-soaked now. Pilgrim (2017), a seven-minute video charting Smith’s journey across sites important to the Black radical tradition, starts with Turiya’s ashram. Shot by video artist Arthur Jafa, the cinematography is woozy and rapt, showcasing a blinding white temple backdropped by the Santa Monica Mountains. We are treated to glimpses of Turiya’s devotional instruments, her organ and harmonium, and her handwritten manuscripts. We watch as two members amble through sunlit grounds. “One For the Father,” the song Turiya wrote for her late husband, accompanies our mystical trek, a divine rush of trembling pianos.12

“Cauleen Smith: Give it or Leave it,” LACMA, Los Angeles, April 1 – October 31, 2021 (gallery view). Courtesy of LACMA.

Cauleen Smith, Epistrophy, 2018, “Cauleen Smith: Give it or Leave it,” LACMA, Los Angeles, April 1 – October 31, 2021 (installation view). Courtesy of LACMA.

After a year of museum closures, entering Give It or Leave It felt like crossing over into a sacred place, with Smith transforming the gallery into a subterranean realm mounted across two rooms. Floor-to-ceiling windows covered in LEE Filters film gels mimicked the colors of the sky at dawn and sunset. Disco balls speckled the floor and walls with twinkling lights like night stars. The ubiquitous white gallery walls disappeared under digitally-printed wallpaper titled Space Station Chinoiserie #1: Take Hold of the Clouds (2018).13 As Christopher Knight observes, Smith’s design is a riff of toile de Jouy, “the popular 18th century style of French wallpaper and textiles that shows imaginative pastoral scenes.”14 Smith embeds a dose of reality into her renderings of fields and trees, describing the wallpaper as a map that connects four utopic sites: Turiya’s ashram in Woodland Hills, Noah Purifoy’s Outdoor Museum in Joshua Tree, Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles, and Rebecca Cox Jackson’s Shaker community in Philadelphia.15 Taken together, these sites provide rich historical models for Smith’s investigations, demonstrating spiritual and creative formations that refute our anti-Black, capitalist, and imperialist society.

Give It or Leave It doubles as a homecoming. Smith, born in Riverside and raised in Sacramento, features multiple California locales throughout, including Dockweiler Beach and Antelope Valley Poppy Reserve. It’s not surprising that Smith would organize the exhibition, at least in part, around California—within U.S. imagination, the Golden State conjures up both utopian and dystopian fantasies. Writer Jane Borden explains that, thanks to the mythos surrounding the Gold Rush and Hollywood, California was seen as a financial jackpot throughout the early 20th century. And because the state, when ceded to the U.S. from Mexico, lacked any particular organizing religion, California appealed to founders of new spiritual movements, intentional communities, and cults.16 Examples include Pisgah founded by Finis Ewing Yoakum, Llano del Rio founded by Job Harriman, and The Source founded by Jim Baker. Opposite the spectrum, California’s extreme climate—fires, drought, earthquakes—and fraught political history often drum up apocalyptic backlash, what urban theorist Mike Davis termed an “ecology of fear.”17 But for Smith herself, utopia isn’t far-fetched, naive, or laughable. As she quipped to VCU’s Institute for Contemporary Arts, “[T]hinking about utopia can’t be worse than the kind of systems that we have people living in now.”18 Rather, Smith is curiously optimistic through her work, revealing how experiments in utopic living have actually existed (if momentarily), and can continue to exist, if we study what came before us to forge our own language of liberation.

“Cauleen Smith: Give it or Leave it,” LACMA, Los Angeles, April 1 – October 31, 2021 (gallery view). Courtesy of LACMA.

Smith’s attitude toward utopia echoes scholar Jayna Brown’s. In Black Utopias: Speculative Life and the Music of Other Worlds, Brown redefines utopia to mean new ways of “being, doing, and imagining in Black culture,” drawing from a range of thinkers that complicate white-centric interpretations, including Turiya, critic and philosopher Slyvia Wynter, and queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz.19 (Like Smith, Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia also envisions futurity as a generative commingling of past and present, or “then and there.”)20 Brown drains utopia of its flat idealism and overassociation with a white privileged class (“hippies”), grounding the concept in queer Black radical thought instead, as a strategy for dismantling normative relational systems. Brown observes, “To miss the moments of intentional and improvised black collective-formation and kinship-making is to romanticize only certain black communities—those rooted in blood kinship, patriarchal institutions, or national affiliations—as authentic and natural.”21

Give It Or Leave It is informed by these intentional and improvised utopias. Structured as a three-part narrative, with numbers on the floor designating the order in which to move through the space, each installation pulls the viewer further and further into Smith’s explorations of being and belonging. The four sites located in Give It or Leave It embody experiments in worldbuilding generated by artists and people of color. These experiments revolve around alternative conceptions of subjectivity and community, ones based in “forms of relationality and reciprocity” that call into question established definitions of family, partnership, and labor.22 Like Brown, Smith seeks to expand our scope of utopia, initiating (im)possibilities of the future through reimaginings of the past, untethered from time and space.

Turiya (Alice Coltrane) at Sai Anantam Ashram, Agoura Hills, California, date unknown. Photo: Sri Hari Moss.

After moving her family to Woodlands Hills, a neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, Turiya focused on building a homegrown monastic community untouched by capitalistic values like competition and wealth. In 1983, she bought 48 acres of land in Agoura Hills, where she founded the Shanti Anantam Ashram (later renamed the Sai Anantam Ashram). Nestled in the Santa Monica Mountains, the ashram housed a temple, living quarters, and its own public access television station and publishing house. Approximately 25-30 students from varied racial and religious backgrounds lived there at a time, sharing the land with native owls, hawks, deer, and trout, their days dedicated to the study of Vedic, Buddhist, and Islamic scriptures. Turiya visited the ashram every Sunday, leading devotional ceremonies, a cherished ritual for all members. Turiya would start the morning with a discourse, providing a word or idea to meditate on for the day, followed by group chanting. Children attended Sunday lessons taught by their parents or other members, learning Vedic concepts like “right action, Dharma, non-violence, truth, Prema (love), and Shanti (peace).”23 This lasted until the evening, when Turiya, taking a seat at her organ, returned to lead the congregation in chanting again for hours, an otherworldly experience akin to astral travel, or what Brown characterizes as “melting times.”24

Turiya’s ashram, along with the other sites located in Give It or Leave It, evokes “otherwise possibility,” a phrase coined by artist and professor Ashon T. Crawley.25 He points to elements of the Black Pentecostal church—whooping, speaking in tongues—as acts that reassemble social relations and create alternative modes of being. Imagination, an emblematic source of power for Smith, fuels otherwise possibility. As an example, Crawley cites maroon communities, formed by enslaved Black people that escaped plantations in the Caribbean and southern U.S. Maroons sought refuge in the woods or in swamps, a dangerous freedom that transgressed legal, social, and ontological boundaries. Their resistance is analogous to art-making: the maroon envisioned new kinships with the material world before translating their visions into practice. “Their imagination was protest, was prayer, and in such imagining they practiced otherwise possibility,” Crawley writes. “It wasn’t about some celestial moment to come but was a striving to breathe.”26

Breathing grounds us in the present; it is a reminder that the quotidian is crested with the sublime. In forgetting to breathe, we feed our sense of lack and anxiety, our desire for more than what we already have in our possession to enact transformative change. In countering this dread, Smith has built a multifaceted art practice, spanning over 20 years, out of speculative investigations that trace the alternative realities embedded in our daily lives. Her work embodies Muñoz’s writing of queerness as a “temporal arrangement in which the past is a field of possibility in which subjects can act in the present in the service of a new futurity.”27 This is the core tenant of Smith’s oeuvre. Her futurity obliterates linear time, melding the then and now via imagined dialogues with radical Black history. She takes inspiration from yesterday’s methodologies, breathing them in, and exhaling them into her own environments.

“Cauleen Smith: Give it or Leave it,” LACMA, Los Angeles, April 1 – October 31, 2021 (installation detail). Courtesy of LACMA.

Like Pilgrim, Smith’s film Sojourner (2018) imagines yet another utopia, overlaying real and fictive moments to create a “cornucopia of future histories,” and generating lush portraits that combine diaristic camera work and performative tableaux.28 Juxtaposing dreamlike pilgrimages with audio recordings of writing by Rebecca Cox Jackson, Sojourner Truth, Turiya, and the Combahee River Collective, the film visits several locations, including the residences of John Coltrane and Sun Ra in Philadelphia, and the Southside Community Art Center in Chicago.29 The 22-minute work, conceived as an exploration of what a Black feminist “radically generous community might look like,” borrows inspiration from a Bill Ray photograph taken, but never used, for a 1966 Life magazine feature on the Watts Rebellion.30 The image, which reminded Smith of a fashion editorial, shows nine chic Black men lounging around the Watts Towers.31 Smith restaged the image with a cast of women and femmes for Sojourner, and switched the location to Purifoy’s Outdoor Museum in Joshua Tree. The decision to relocate her utopian feminist dreamscape to the harsh, barren terrain of the desert seems like an ironic jab at the “ecology of fear” that pervades the land. Smith, though, directs us to consider the otherwise networks that survive in spite of the volatile social, political, and environmental conditions of recent years—organizations like L.A. and Inland Empire-based Feed Black Futures, which promotes food sovereignty within Black communities via food distribution, skills sharing, and support of Black farmers.32 In company with Smith, collectives like FBF continue to look toward the future, modeling new forms of living and relating, imbuing the community with ideas of abolition, anti-colonial revolution, and interdependence, and harnessing creative imagination in the service of tangible change.

Cauleen Smith, Sojourner, 2018, single-channel video (color, sound), 22 minutes (still). Courtesy of the artist and Corbett v. Dempsey.

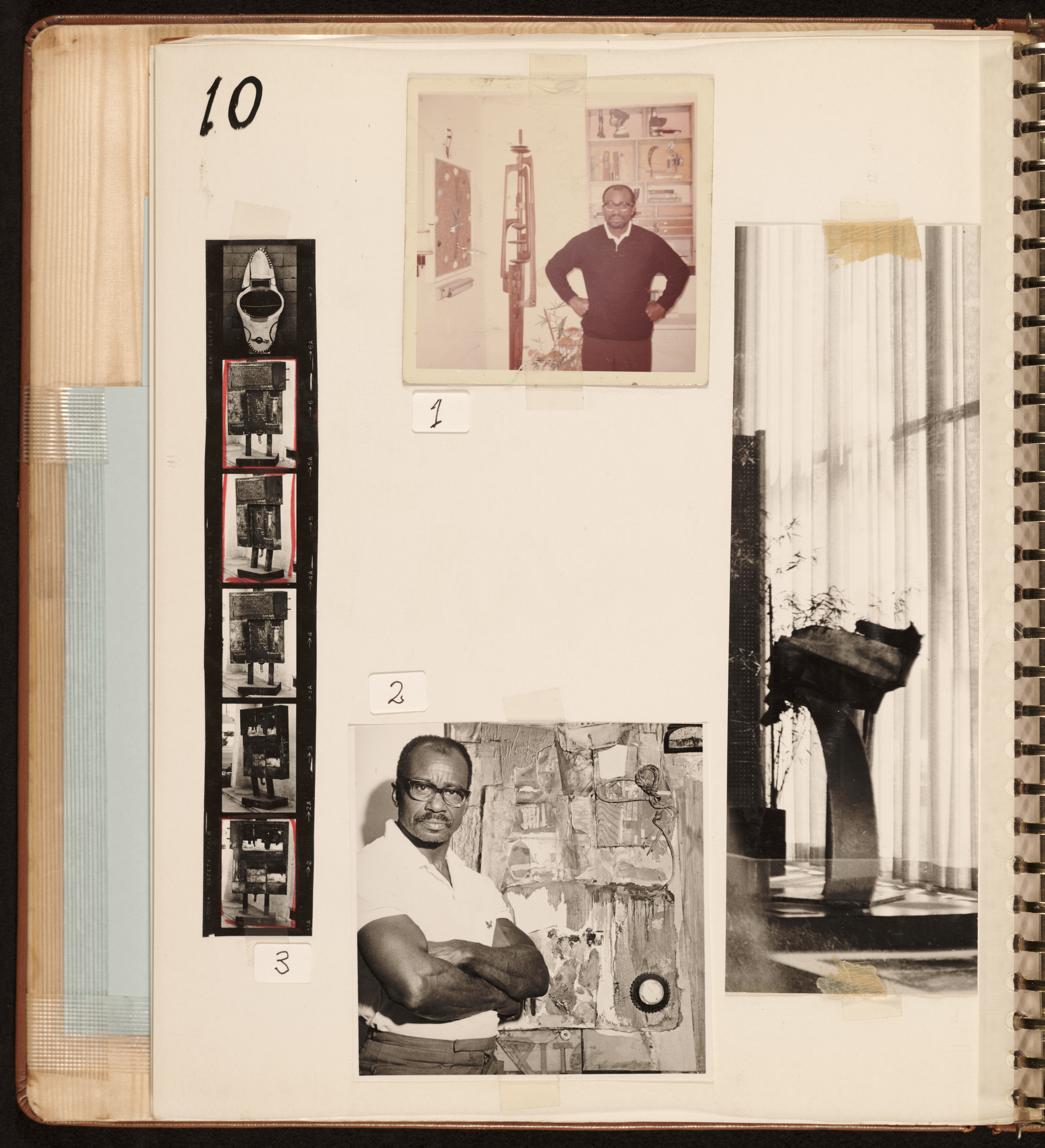

Smith’s desert in Sojourner reflects Noah Purifoy’s own embrace of the Mojave landscape. During his early career as an artist and sculptor, Purifoy was positively driven by the notion that art could bring material and psychic change to our lives. Trained as an industrial arts teacher and social worker, and influenced by philosophical discourses like phenomenology, Purifoy sought to eradicate elitism associated with art making, instead grounding it in the community—L.A.’s South Central. In 1964, he co-founded and was the first director of the Watts Towers Art Center, which quickly became a creative hub for local residents.33 In a small bungalow next to Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, Black youth could take classes in visual and performing arts, and attend exhibitions and concerts. The center also created job opportunities for local working artists that included John Outterbridge, Suzanne Jackson, and Senga Nengudi. Purifoy hoped to realize art-as-change, employing creative practice as a tool for self-actualization and communal healing. He emphatically did not view art as a means of expression set aside for the privileged and talented, and stressed that creativity could be a vehicle of liberation for the oppressed.

The Watts Rebellion had a profound effect on Purifoy’s aesthetic, moving him to work exclusively with found junk items. Along with artist Judson Powell, Purifoy collected three tons of debris from the aftermath of the August fires, sculpting charred trash into fantastical assemblages.34 “Junk … had begun to haunt our dreams,” he would later say.35 Powell’s and Purifoy’s obsessions culminated in the seminal traveling exhibition, 66 Signs of Neon. Art historian Kellie Jones writes that his interest in assemblage, and thus “linkage and connection,” makes sense when considering his efforts to merge art, community, and personal transcendence, first as a grassroots organizer, then as a cultural worker (he was a founding member of the California Art Council and served for 11 years).36 With 66 Signs and his other community work, Purifoy demonstrated his belief that “education through creativity is the only way left for a person to find [themselves] in this materialistic world.”37 Art, for Purifoy, had the potential to transform consciousness, rewiring the heart and mind for greater communal good.

Noah Purifoy, “Join for the Arts” scrapbook, ca. 1965-1970. Noah Purifoy papers, 1935-1998. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

By the late 70s, however, Purifoy had become disillusioned, frustrated by the unnecessary bureaucracy of the art world and his own changing perceptions. In 1989, when he was 72, he rejected the commercial trappings of the world altogether, retreating to Joshua Tree, where he remained until his death in 2004. (Another reason for his move: he was priced out of Los Angeles and his artwork wasn’t bankrolled by a gallery). The desert provided him time, space, and solitude to construct his monumental environmental works without the distraction of market demands. Across ten acres of arid Mojave land, Purifoy built his Outdoor Desert Art Museum, a compound of 120 architectural installations constructed from junk and debris, some resembling skeletal housing that visitors can enter and explore.38 Shelter (1999), which features charred wood salvaged from a neighbor’s burned house, looks like both a playfort and a makeshift encampment. The piece, inspired by Purifoy’s time as a social worker during California’s Reagan administration and the ensuing rise in homelessness, was envisioned as a sort of safe haven. Much of Purifoy’s Outdoor Museum reimagines personal and collective symbols: his childhood home in Alabama, segregated drinking fountains, voting booths, a stage, bridges, classrooms. Through this Purifoy transforms the rural desert plot into its own “miniature universe,” his site for creative excavation and metamorphosis among the cholla cactus and yucca.39 “I wanted art to be a means of finding answers to questions like, ‘What is growth?’ ‘What is change?’ Life isn’t worth living unless the individual is pushing to understand more,” he once explained.40 Within the mini-verse of Purifoy’s desert, art-as-change becomes literal; wind, sun, and fauna have warped and eroded the artist’s sculptures over time. He welcomed this change, regarding nature as his spiritual collaborator.

Noah Purifoy, Outdoor Desert Art Museum, Joshua Tree, California. Photo: Dominque Vorillon, As Is: Noah Purifoy, Joshua Tree, East of Borneo, 2016.

Noah Purifoy, Shelter, 1992-93, Joshua Tree, California (interior view). Photo: Dominque Vorillon, As Is: Noah Purifoy, Joshua Tree, East of Borneo, 2016.

Like Purifoy, by the 1980s, Turiya stopped working commercially. No longer interested in tours or album sales, she continued to develop her own iconoclastic sound at the ashram. “Swamini often used to say that the highest expression of any art form is divinity,” one former student recalled.41 Turiya stressed that everybody had the ability to tap into a higher energy by cultivating this awareness in themselves. Her sacred music, which blends sounds of her Detroit upbringing (gospel, bebop) with the Hindu devotional music practiced in her Vedic studies, was distributed freely on cassette tapes within the ashram.42 After her death in 2007, the ashram continued with its teachings and services, eventually closing in 2017. One year later, propelled by dry conditions and fierce Santa Ana winds, the Woosley fire ignited near Simi Valley. By the following morning, the fire had jumped over the 101 Freeway, swallowing up Malibu and Agoura Hills before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Turiya’s ashram was destroyed. It would be easy to read its destruction as yet another strike against utopian possibility, but as one member points out: “The ashram is not the land. The ashram is wherever someone is … making that connection with the divine … that’s where the ashram lives.”43 We are more so encouraged by artists like Turiya, Purifoy, and Smith to locate the otherwise, a state of awareness that collapses the gap between imagination and protest, creativity and liberation, here and there. It is the understanding that the destruction of one world begets the formation of another. The fire may consume our earthly possessions, but it also clears space for new growth.