Printed Matter Virtual Art Book Fair: Tom Lawson in conversation with Fiona Connor & Emma Kemp

by Thomas Lawson

Nika Simovich Fisher, “Foreshadows: A Series of Slides & Captions,” from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

On the occasion of Printed Matter’s 2021 Virtual Art Book Fair, East of Borneo hosted a book and edition launch to celebrate the release of Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed (East of Borneo Books, 2020) and Classroom Furniture, a limited edition artwork by Fiona Connor. East of Borneo Editor-in-Chief Tom Lawson joined artists Emma Kemp and Fiona Connor in conversation to discuss the role, function, and value of arts education during the sudden transition to remote learning spawned by the global COVID-19 pandemic. As artists and as educators, what do we do when institutional legacy—and memory—is out of sync with reality?

Emma Kemp writes non-fiction and teaches at Otis College of Art & Design. She received an MFA in Writing from California Institute of the Arts and a BA from Central Saint Martins in London, U.K. Born in New Zealand, Fiona Connor is an artist based in Los Angeles. Vital, recurring concerns in her work include the social and psychological life of the object, the politics of thresholds and mimesis, and the ethics and aesthetics of the built environment. Fiona Connor has made solo exhibitions at Secession, Vienna, SculptureCenter, New York, MAK Center for Art and Architecture, Los Angeles, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, Monash University Museum of Art, Melbourne.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion, which was held via Zoom on February 27, 2021. Speakers include Adriana Widdoes, Tom Lawson, Emma Kemp, Fiona Connor, Leslie Dick, Nicholas Angelo, Janet Owen Driggs, Jaya Kang, Nina Waisman, Teresa Kemp, and Curt Widdoes. This discussion was free and open to the public.

***

Tom Lawson: I just want to talk a little bit to get us started, about how all universities and colleges—and particularly art schools—are the physical manifestation of the network of ideas, and it’s all about the creative connectivity of being in place, the conversations in class and in the hallways, the word that there’s an exhibition or a performance to be seen and then going to see that and talking about it later, following up with studio visits, a lot of random conversations in the hall, showing up in somebody’s class—typical school work in some way, but it is what allows us to generate and develop ideas. And so when all this was suddenly gone, pretty much a year ago, we were bereft. We went through a period of grieving and various attempts to accommodate this particular grid system offered us by Zoom. And behind that was always the hope that we would be returning soon to our usual haunts. The photograph behind me represents that hope. It is of the hall in front of the Bijou at CalArts, usually the hub of the whole college, filled with signs and posters and notices and people. I took this picture last week. The whole building, of course, is deserted currently and it’s so, you know, disappointing. I think that in real and interesting and complementary ways the two projects that we’re looking at today, the Remote/Control book and Fiona’s artwork, both address this sense of loss and offer some attempts to build a reconnection to an idea of what might be possible now, and in the future. And so that’s what we’re going to try and talk about. I hope I can stay connected to keep the conversation going.

I think it’s good to start with the book because the project started very quickly as a response to the shock of teaching online, and it lays out how the various contributors were trying to deal with that and how they were reflecting on it. So perhaps Emma can talk a little bit about how it got started and how it developed.

Emma Kemp: Thank you, Tom. And thank you, Adriana, Jaya, and all the contributors for supporting the project. I’ll share my screen so you can see what the book looks like. It’s called Remote Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed. But really, this is a collection of field notes from art and design educators. Most of the contributions in the book were produced between March and July 2020 when schools, colleges, and universities were responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, launching remote classrooms, and responding to the strategic anti-racist organizing that was happening across the country. And so for me, as an educator, this was an incredibly powerful moment. Also a very difficult moment. I think all of us—students, educators, staff—were forced to reckon with the reach and also the limits of the institutions to which we are connected.

I’m going to read a short excerpt from the book that I think sets up some of the broad concerns across the project. It’s from a piece called, A Call for Complaint: For Plague Speech, For Sick Speech. The author of this piece wrote it with the intention of remaining anonymous, which we’ve honored:

Over the past two weeks, as the crisis has unfolded, we have listened very carefully as faculty, as staff, as students, to people in power. We have listened, waiting, for the language that meets our intelligence and our energy and our labor and our criticality. We know we deserve more than performance, more than self-congratulation. In response to students asking for tuition refunds, art school deans send videos of themselves dancing, mostly proud of knowing how to attach a video to an email. The heartbreak, the sharp, informed critique of students, is met with a shrug, a show of unfathomable callousness.

What can our speech sound like now, outside of the institution? Even as we have returned home, we have carried our frustrations, our sense of what we know was not quite right, our politics, with us. We carry our complaint. Just because we have gone home, we don’t start over. We carry our individual histories, and memories of our time inside the institution, home with us. As we are now asked to continue our contract from our homes, we can pause to remember our complaint.

We might not have begun this crisis as critics, or had any interest in dismantling, deconstructing, or destabilizing a place. The virus has revealed on every level the weakness and failures of institutions, scrambling to assert their mandates. It has revealed how the institution speaks, how it hears selectively. We treat it as a person, as it desires. Crisis creates a rupture, a profound vacuum, which reveals the possibility of other spaces of learning, of better worlds we want to live in.

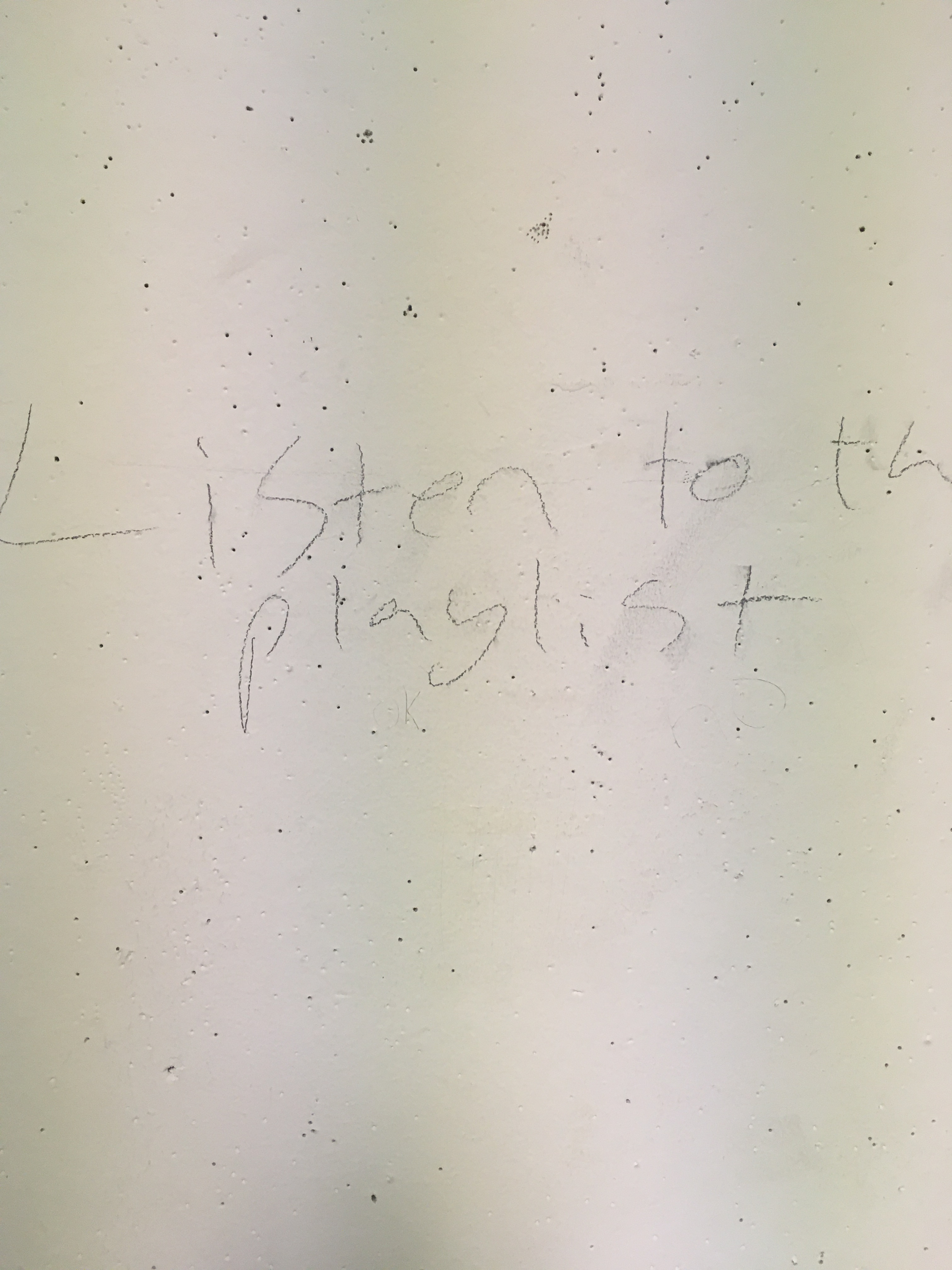

What I want to stress about this book, and why I’m so proud of it and excited by it, is that it really is a collection of notes and drawings and fragments that form a body of evidence, shared by fellow art and design educators who documented—sometimes scrappily, hastily, or partially—what was felt right at that moment of rupture. It affirms what we experienced at the onset of this social crisis. It really is a way of remembering; a kind of memory book. I love reading and writing, and I think that publishing—independent publishing, DIY publishing, digital publishing—all of these harness the potential of seeding and spreading ideas. What I was interested in when I had the idea for a book was ensuring that, as we were experiencing this sudden radical break with the norms of our classrooms, we documented what was happening and what we were feeling, because I was anxious that the drive towards recovering “normality” would very quickly disguise the urgency of the moment and obscure the gains that could only be made through such urgency. And so the book exists as this strange and messy and beautiful and complicated collection of reports right from the heart of it. I think in that way there’s a connection to Fiona’s work as well.

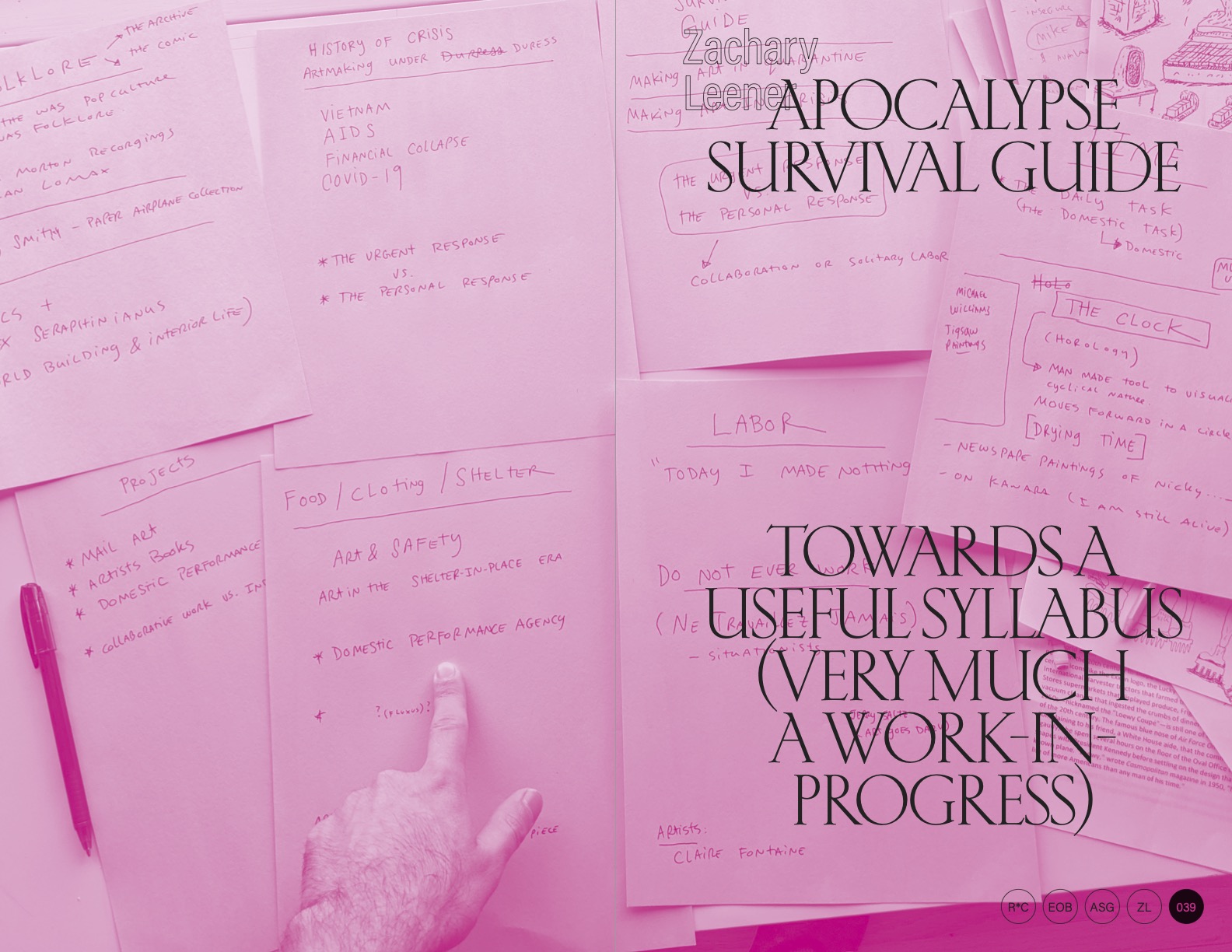

Zachary Leener, “Apocalypse Survival Guide: Towards A Useful Syllabus (Very Much A Work-In-Progress), from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

Janet Owen Driggs, “RE: [External Sender] RE: Janet!! hi!…,” from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

Fiona Connor: It’s a really remarkable publication and I love how it’s so responsive and puts things on the table and moves the conversation around, and maybe forward, for people to enjoy it. I really enjoyed reading it, so thank you for that. And now I’m going to read something I wrote about how my work was produced:

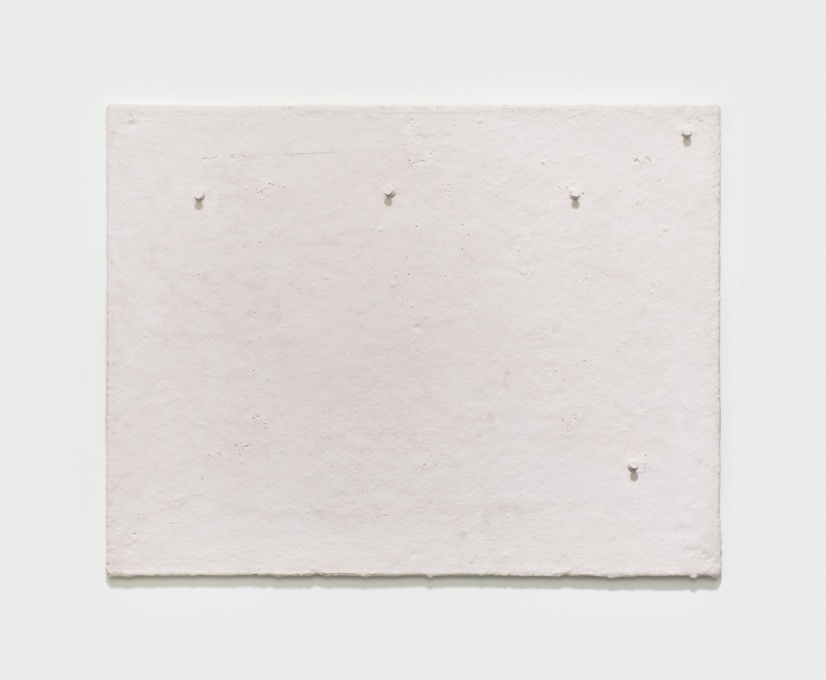

For a while, I had in my mind to make cast replicas of all the bulletin boards at CalArts and I spoke to Tom and he was into it. When the school was vacated for Winter Break in early 2020, I started making silicone molds of the bulletin boards that line the hallways and are hung on doors throughout the Institute.

The surfaces show the signs of previously working notice boards and occupied hallways where students, faculty, visitors, and staff moved round—buzzing in all directions, rubbing up and seeing each other out of the corner of their eyes.

I moved round these locations with a trolley loaded with silicone, layering coats to build up the mold.

Outside A402, Level 4;

Stevenson Blanche Gallery, Level 3;

Outside D300, Level 3;

Outside A217, Level 2;

Outside the Print Studio, Level 1;

Outside the Gamelan room, Level 1;

Outside Mac Lab/A112, Level 1;

Outside Film School office, Level 1;

Outside Music School office—

There is a very special room on Level 3 which is run as a student gallery that has 8 doors coming off of it. Stevenson Blanche.

Now the painted white surfaces of the interior spaces are like a skin. When I imagine it now, it is like an actor—emptied out, holding space; a husk. There is you, me, us, the building—we are all separated by great distances. The triangulation creates new territory.

Can you hear me, can you hear me now?

Like a dysfunctional bureaucracy, communication stutters. The line oscillates between an electrical pulse and dead air, but we somehow remain on the line. When I am back in the studio, I reinforce the molds and make resin casts. The cast boards are like skins, very light.

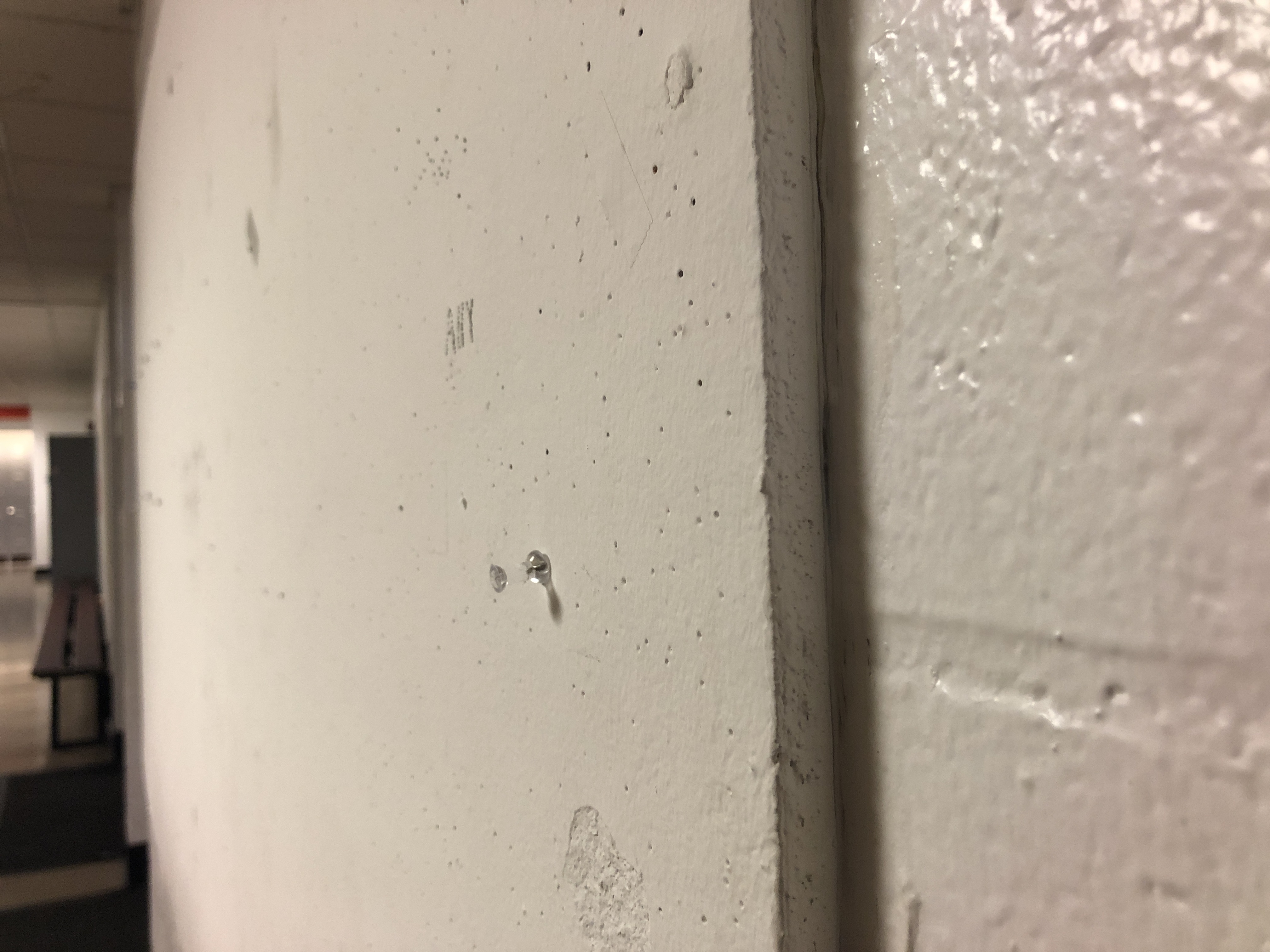

I’m not in Los Angeles right now, but I want to introduce and spotlight Kira, who is in my studio and who is actually going to show us the work through her camera. It’s a cast bulletin board from Stevenson Blanche. It’s kind of hard to make out, but there are pushpins on it. And Stevenson Blanche—particularly the surface of it—there’s a lot of personality in it. All of the corners are soft with all the layers of things.

Detail view of Fiona Connor, Classroom Furniture (24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia, CA 91355), EOB, 2020; pigmented resin, 16 inches x 21 inches x 1 inch

TL: I think these two projects are so moving, and I am very pleased that we were able to publish both of them at this moment. Emma gathered the words of a range of people directly experiencing this new form of teaching that is euphemistically described as “remote” to capture the feeling of sudden disconnect. And as a result, the book gives us a snapshot of a moment; it is very present, while Fiona worked with the silent eloquence of a few pins and bumps on the surface of empty signboards, referring back to something recorded in the past. And just to get the conversation going—Emma, I was wondering about a passage in your essay in the book about raising the question of how we empower others. You just raised it as a question, but I wondered if you’d had time to think about answers to that question.

EK: The essay that I contributed to in the book is called Complicit Love. It’s sort of named for this idea that I read in a different essay called A Conspiracy Without a Plot. Maybe some people here have read it. It’s by Valentina Desideri and Stefano Harney, and it’s about all these possible arrangements that educators, artists, curators, and people in general can have with one another. And it sets up this idea that as a teacher, or as an organizer, it might be helpful to relate to others through the role of an accomplice. I was thinking about what that would mean in the context of being employed by an institution. What would it mean to be an accomplice primarily in relation to my students? And who does that set me up against in the scope of the institution?

One of the reasons the book is called Remote/Control initially came from a feeling I had when the institution where I teach first went online. There was this sense that the machinery that held the identity of the institution together was really trying to exert control as things were just sort of disintegrating, as we were all moving away from this kind of physical space. And there was almost a prerogative of policing and of surveillance that was occurring through the digital platforms we were being encouraged to use. So then I was thinking, well, where is my allegiance here? Does it have to be a contentious relationship? I’d rather it not be, but it kind of feels like that, and I’m choosing to align myself with the students. That’s my notion of complicit love.

There’s a quote by Toni Morrison that I reference in the essay. She’s talking to her students and she’s saying, well, when you get the jobs that you’ve been trained for, remember that your real job, if you’re free, is to set somebody else free. So, in other words, there’s your job description that you implement as a condition of your employment, and then there’s your job, the thing that you’ve got to do as a condition of being free. I included that quote in my essay because it resonated with me in terms of my relationship to the institutional body, to my colleagues, and to the students. You know, the teachers are here, the students are here, the thinking is still here. We’re all still doing this job because we’re still doing this work. What’s missing is access to this shared physical space, and that’s a loss for sure. It’s a huge loss. We can’t bring our bodies together.

What I love about Fiona’s work is the way it captures the objects that constitute this memory of a shared space and the interactions that happen. I suppose I see my role in the classroom as trying to facilitate these kinds of conversations even in the absence of a shared physical space. And I see the book as an extension of that, as a conversation with other educators who are trying to think through the same complexities.

Installation view of Fiona Connor, Classroom Furniture (24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia, CA 91355), EOB, 2020; pigmented resin, 16 inches x 21 inches x 1 inch

TL: There is so much to think about around this notion of being an accomplice. It is an idea that has been really generative to me as I have come to understand my role at CalArts, navigating the administrative requirement to establish and maintain order while allowing space for students to do what they must to create work. And the Stevenson Blanche Galeria, to give it its original name, is actually an example of this kind of collaboration—an overlooked space given purpose in response to a particularly rebellious student at a particular moment, who absolutely demanded more space to show work without the kind of rigmarole that we put in place for the official Art School galleries. I’m sorry, I’m in a kind of retrospective mood these days, but it’s nice thinking back on it.

Fiona, I’m curious—I mean, it was good hearing you talk about being in the building with your equipment, your trolley loaded with silicone and your tools. Was the building already deserted when you started this project, or did you just have a premonition that this was going this way?

FC: When I made them for the first time it was just winter break. I think it was the first weekend of 2020. But then I went back and did a second lot after Covid was there.

TL: Did you sense a difference in the atmosphere of the building? Because I would just say that I’ve been there during Christmas break or summertime and it’s quiet and has a certain sort of hushed quality to the hallways. But the way it feels now is really very different, there really is nobody there. There’s someone in the security office to check you in, and then you see nobody. And that is disturbing. I mean, the whole point of the building is to facilitate conversation and the exchange of ideas, and there is no one to talk to.

FC: Yes, definitely, it felt different. I think when you go to campus during winter break, you’re kind of feeling like you’re cheating the system a bit because everybody else is away. I think a lot of artists work during holidays because it’s a time when things are a little quiet. You can maybe afford a bit more time. But when I went back and the building was closed for Covid, there’s sort of like a hammer, a binding agent that’s in the air and every interaction you have with facilities staff or whatever. When I was casting in Stevenson Blanche, there was a parent of a student there, and they were clearing out their studio for them. We actually got into a really long conversation and perhaps in more of an intimate way than we would have been if the building wasn’t locked down. It’s just such a weird thing. There’s a wastefulness that there’s this big building holding space for when it can start up again. I’m not sure if I’m the one to speak with authority on it because at this point I’m an alum and it’s not my day-to-day. I’m not working there. So I’d be interested to hear about the way other people are thinking about it.

EK: I think the book gets to this set of contradictions about how we are both grieving for this loss of space and, at the same time, there’s a way that physical space functions as a marker of access or privilege. There’s simultaneously a formality of classes on campus where there’s this kind of tyrannical and packed schedule and, you know, it’s mandatory that everyone has to eat lunch within a certain time frame. So there’s something about suddenly being able to step back from the architecture—not only the physical architecture but the organizational architecture of the institution—and to consider spaces for study that loosen some of that formality without the indignity of public gendered bathrooms, or being able to eat lunch at whatever time you want. There’s a loss of connectivity, of shared physical and sensual space, but there’s also something to be said for stepping away from the place and being able to view it from the outside and really see what we were actually inhabiting. And now when we do return—because we will return in some form—what do we need to change? For me, a big part of the book was trying to remember what there is that we want to change because schools so very quickly want to normalize the situation and go back to what we had prior. And I want to say, well, what are we going back to? Because I actually think that needs to shift.

TL: I think that before this we were all very suspicious of online learning and were seeing it as a way of infiltrating a cheaper form of teaching into the curriculum. But I suspect that we may have discovered some benefits, and that there are some productive ways to rethink the way we use time and space. It could be really interesting if we give ourselves the time to think it through properly, not just get panicked and say, ”Oh, we’re back to normal and we’ll just go back to teaching like we were doing it before.”

FC: And then also how can art feature in that statement, you know?

TL: Yeah, we’ve got the same thing with art, I mean, the question of viewing and distributing art is also at stake at this point.

Cara Levine, “To Recognize Our Humanity,” from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

EK: I just love that experience we just had of viewing Fiona’s work on Zoom from the perspective of Kira’s laptop camera, kind of like viewing the work as an interface. There are some lovely relations that can emerge through the screen under the right circumstances. But I think the conversation around online teaching is huge, and there’s a big difference between a MOOC course and those PDF downloads with 1,001 creative prompts for artists where you’re instructed to draw a picture with your eyes closed—essentially radical pedagogy. Then there’s also spaces like The South Land Institute and Dark Study. A colleague of mine, Silas Munro, has this studio called Polymode with design history courses. There’s lots of really innovative pedagogical work appearing in the online space that has been accelerated because of this massive shift in general, so I’m excited by some of that. I think in the book you see this tone of anxiety that Tom mentioned, the fear and the skepticism about learning online. I had that, too—and my thinking has shifted massively over the last year. I’m still really happy that the book documents that fear and anxiety, because I think that is important to acknowledge.

TL: And to remember. We do have to remember it. But we also have to acknowledge this newly normalized ease of connection across time and space. I mean, right now, Fiona, where are you?

FC: Auckland, New Zealand.

TL: That element of this technology is amazing, that we can be in the same time together across the globe, which means we can open up conversations that beforehand were very hard to imagine. Earlier today, I was remembering an event sometime in the early 90s. Tom McEvilley was briefly doing something at UCLA and created a satellite connection between his class there and a group in Tokyo and another group in Berlin. He invited art students and teachers from the L.A. region to come down to UCLA to join in this moment of planetary connectivity. And it was not very successful—mostly static and dropped phone calls. But it was alive with optimism, an optimism that was quite fabulous, around the idea that we could, with technology, reach out and speak to each other across the world in that way. And the irony is today, with all the improvements in technology, here we are with my connection constantly failing. My connection here is failing all the time, but we’re sort of managing. I wonder if this is a good time to open up to the rest of the people here and see if anyone else in the room has a question or a remark or an observation.

***

Leslie Dick: I’m really struck by the bulletin board because my office at CalArts is in Stevenson Blanche and, working with new MFA students, I always have to explain to them how there’s this traditional analog interface where little notes are exchanged if they want to have a meeting. Maybe five years ago it stopped, but for 25 years before that, if a student wanted to have a meeting with me, they would leave a note on my notice board on the door of my office. And the note would sit there until I physically went to my office, took the note off, and figured out when to meet. I would write back to them by leaving a note on another big bulletin board in the Art School office. And it would say, how about Thursday at 2:00 p.m.? And then you would have to leave another note for me saying yes or no, and there was this kind of materiality of connection. The shared space that it implies, the bodies in the space that is implied through this, seems to me very powerful and reminds me of Michael Asher’s work because his commitment to the teaching practice was so much about shared space and unlimited time together in one room. The conversation and being in the same space is how discourse is formed.

When we move to Zoom and email and text and so on, it’s fantastic, but what is lost is almost a kind of Marxist apprehension of the way that economics, class, race, and all these structures actually take form in architectures—authoritarian or anti-authoritarian, hierarchical or nonhierarchical. So to me, there’s something very frustrating because it’s really hard to challenge the screen. You cannot break the face of the screen, you can’t do it. It wins every time. And yet somebody could have left a note on my office door that was an obscene drawing or a love note or an artwork or, you know, so on. There’s this excess of possibility that’s in the material analog interface that I really touch and connect to my experience of art. I like being in the room with the artwork. I don’t want to see any more art on the screen, even though that’s how I do it, so I appreciate what Emma said about Kira holding the laptop up to Fiona’s bulletin board. But I’m really glad that there are other ways to see it, too.

Adriana Widdoes: Thank you, Leslie. I also wanted to offer up a question regarding some of those thoughts. Looking at Fiona’s work, I feel very emotional when I see the pinpricks on the bulletin board. I don’t know why, but it feels like being visited by a ghost, and there’s obviously this level of intimacy to it. Reading the book, it also feels very intimate, especially some of the email exchanges that were printed from right at the beginning of the pandemic. There’s a lot of emotion behind it, and this anxiety and fear wrapped up in all the intimacy. So, just to pose the question, has anyone had any new or novel experiences of intimacy over Zoom, or in any kind of remote, online situation? Has anybody been able to locate that same kind of intimacy held in the pinpricks, but in a different form? And where has that moved to, or has it not?

Nicholas Angelo: I’ll say something pertaining to Fiona. It was last April when I saw Fiona’s lecture and realized I wanted her expertise on something I was working on. And we connected really quickly. I emailed Michael Ned Holte and he connected me with her and then we met over Zoom—and Fiona, you literally gave me answers to a project that worked out incredibly well for me. I guess I shouldn’t tell Tom this, but I never take the direct advice of my teachers at CalArts, and yet I was really happy with it. And I think had we met in person it might have been something completely different, but because of the screen, because of the physical distance between us, that project manifested itself the way that it did. I think there’s something to be said for the way that artworks are manifesting differently now between mentor and student, or artist to artist, because of screen interactions rather than physical interactions. I think it’s very momentary.

TL: I just have to say that I don’t believe that you’re supposed to take direction from us. We offer insight and encouragement and suggestions.

EK: In response to what Adriana was saying, I agree there is something really powerful about the impressions of human interaction on the notice board, the pressure marks of the pins, the fact that we know someone wanted to communicate something of importance and share that with someone else. Hearing Leslie talk about the way that she and her students would organize and arrange, there’s something about slow time that I lament as someone who is now so entrenched in a digital time space, which is to say that there’s this expectation of constancy and immediacy in terms of how we correspond. Now that school is on Zoom, now that we have to be emailing constantly with one another, there’s this sense that I have to reply to all emails within 48 hours. It’s actually institutional policy. You have to reply within 48 hours even if it’s a Sunday evening or a holiday. And there’s just something about the life being lived in between those messages that are being pinned. Leslie would pin something for a student and life would happen, time would pass, and there’s something about that. If we think about study as living and building upon life experiences, it’s almost like the educational structure we have excises life and living from the schedule so that we’re just in class all the time, or emailing all the time. But how do we slow down? How do we really live and allow that to be studied?

FC: I think that’s a really good point, Emma. What about having fun, right?

EK: Yes, and one of the things I found with my Zoom classroom that I’ve been trying to embrace is the fact that students are now living with other people, oftentimes family members or partners or lovers or siblings or caretakers or pets. Sometimes you see these figures in the periphery of the Zoom window and it’s someone’s mom or boyfriend. I’m trying to make space for the fact that my students’ educational situations are now likely sites of cohabitation, versus before when a student would leave home and go to the classroom as an individual. I mean, you can have your dog with you in class now, which is fantastic. I guess it’s what comes to mind in response to Adriana’s question about where intimacy and vulnerability has moved. The other day a student Zoomed into class after having just taken their first driving test, while their dad was driving them home from the DMV. And so there are these interesting ways in which a fuller scope of the student’s life is entering into the classroom, but they come with sacrifice.

LD: Quickly, I want to say that I recently read a short piece by a teacher who realized that his teaching deteriorated the more black rectangles there were from students who had their cameras turned off on Zoom, to the point where he thought he was teaching really badly. So at the beginning of the next semester, he told his new class that if two thirds of the class were black rectangles, his teaching is much, much worse. And he said since then they have managed to keep it so that only approximately one third of the students’ cameras are off at any time. So when one student turns their camera off, someone else will turn their camera on, in this kind of flip-flop. What interested me about it was, of course, it’s a very, very vulnerable thing for a teacher to say, especially a university professor, and apparently the students’ response was to say, well, we never thought of that.

EK: That’s fascinating because yes, it’s extremely vulnerable for the instructor and at the same time, you can see how the students are cooperating with his needs in a way. There’s a reciprocity between the students collectively and the instructor. And I think that’s an incredible show of respect, and the respect that the classroom can establish.

LD: Or simply, they want him to be a good teacher because they’re paying so much money, but they don’t want to hear that it’s teaching.

TL: There is a silence that we can allow in the classroom. When we’re in the room together, it’s OK to be quiet for a bit. But a pressure builds such that someone eventually feels they have to say something. You can’t really do that so well on the screen.

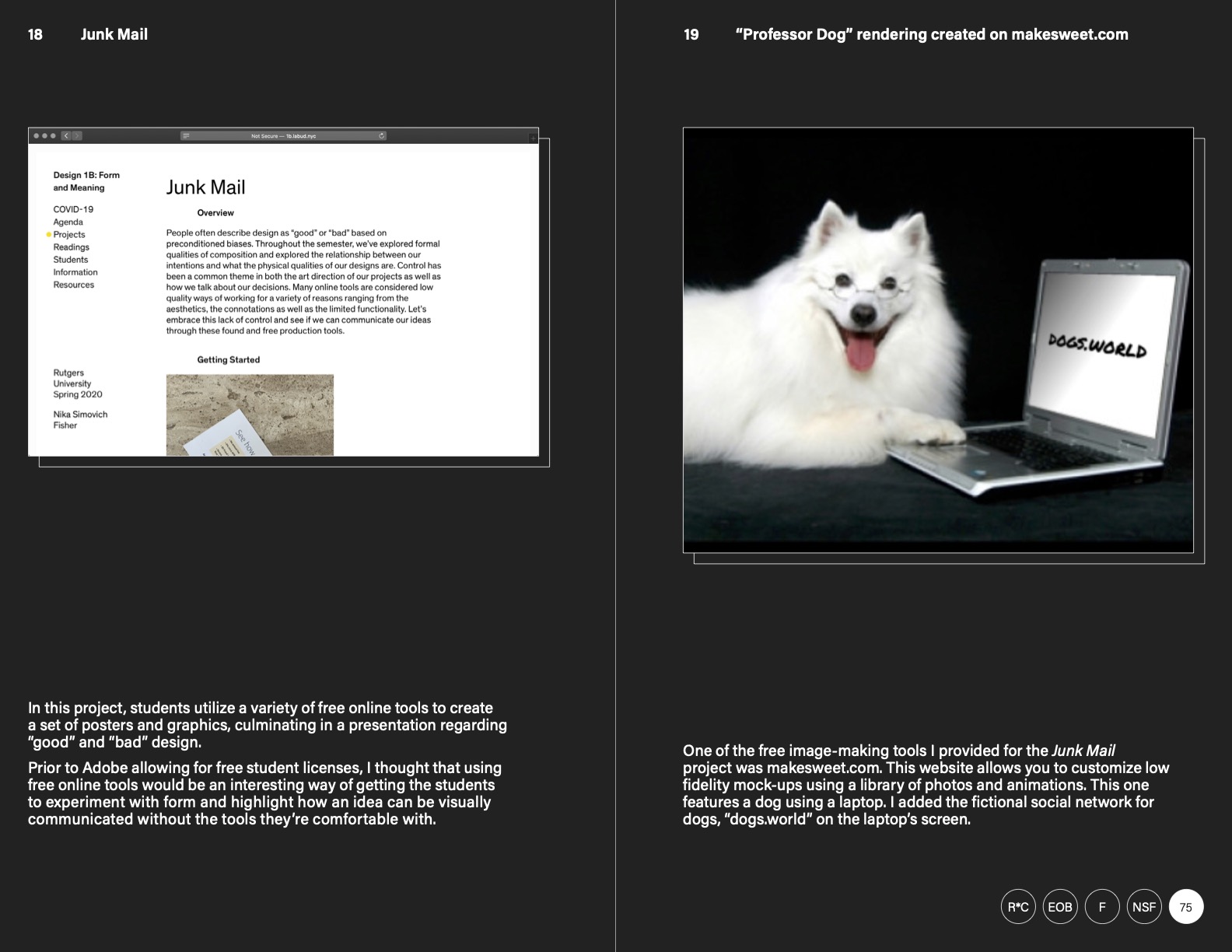

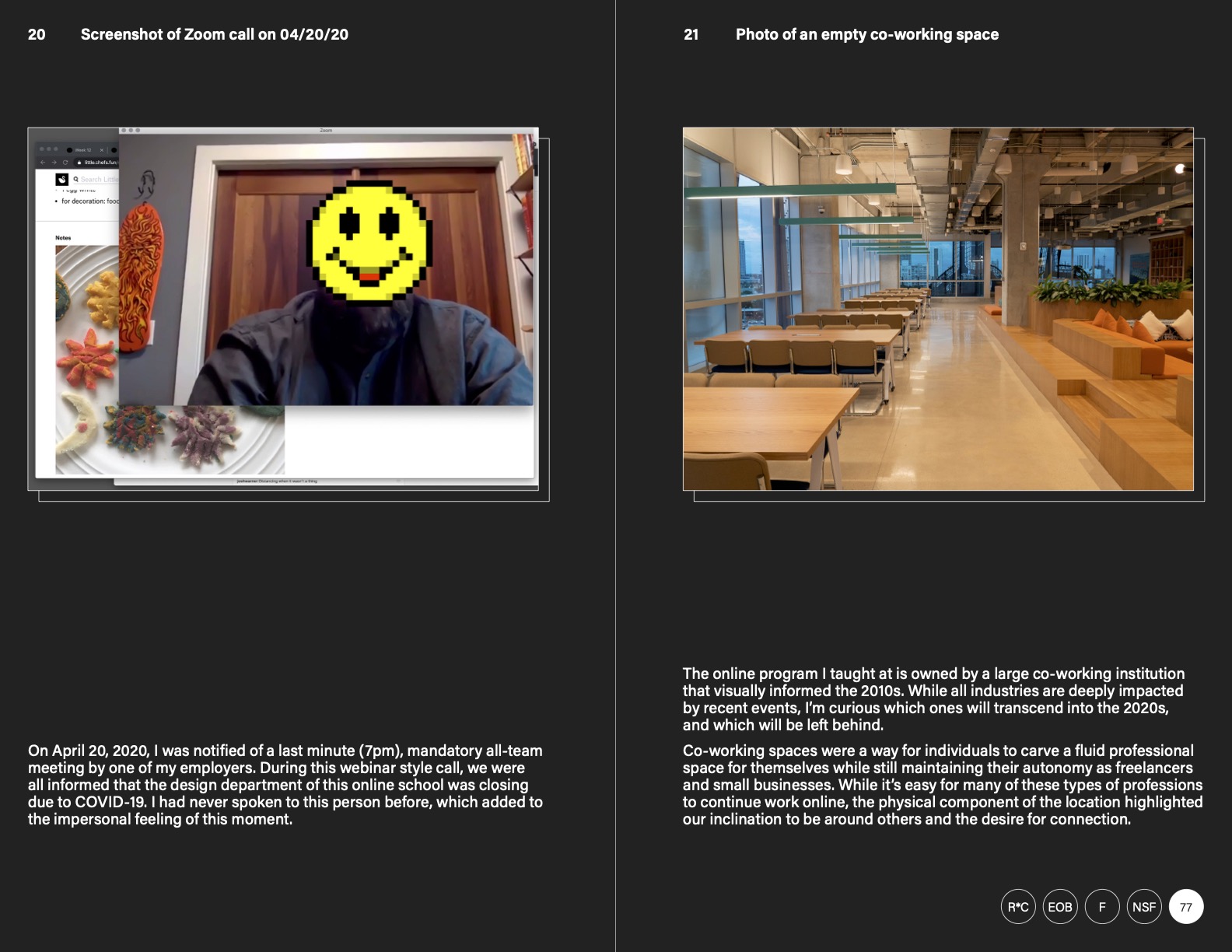

Nika Simovich Fisher, “Foreshadows: A Series of Slides and Captions,” from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

Nika Simovich Fisher, “Foreshadows: A Series of Slides and Captions,” from Remote/Control: Astral Projection in Higher Ed, East of Borneo, 2020

Jaya Kang: I have a question going off of that as well. There’s this persona that you take on as a student when you’re in an institutional space, and there’s a very different persona, sort of like a shedding of that student, when you’re in your personal space in your home with your family. A lot of times, stepping into an art studio or classroom allows you to shut off, temporarily, from those relationships with a dependent child or partner because you take on a persona according to your relationship with the space you’re in, and with the people around you. I’m wondering how or whether that affects the level of education a student is able to effectively take in. As educators, is there a difference in how you see your students taking in information?

EK: That’s an incredible question and probably other educators in the room can also share their thoughts. I think there’s a tension between the kind of professionalism that both the instructor and the student try to perform in the classroom. At the beginning of the pandemic, there were these articles published in the Chronicle of Higher Education that were advising instructors to make sure we had the appropriate books on our bookshelves behind us on screen, so that your students know you’re serious. And, you know, don’t wear your pajamas to class. I’ve sort of taken the opposite tact. I mean, I’m not wearing pajamas yet, but I’m trying to acknowledge the reality. That’s not for everyone, but I want to acknowledge that people have living situations which are broad and varied. But for the most part, I have been seeing students feel more comfortable in the space actually, and a different kind of vulnerability in the conversations that we’re having.

Nika in the chat is saying that she’s noticed students having to take more responsibility for how they learn because they’re having to work within the limitations of their own space. I think that is also true. And the variation of circumstances for students is hugely dependent on their economic situation and class and all of these different intersections, so I think for some students it’s working well. I think for other students the challenges are so huge that it’s difficult for them to learn and to absorb the same knowledge.

AW: I’m not a student anymore, but I remember being a graduate student at CalArts and feeling so desperate to prove myself creatively and intellectually and as a professional. I really wanted to be seen in the classroom as being the same as the faculty and the artists that I admired. And I think in a way being on Zoom has enabled me to shed some of that performance instinct within certain institutional and professional spaces. But there’s still plenty of performance going on on Zoom. I mean, even today I asked someone if it was OK that you can all see the inside of my apartment during this talk. You know, is it OK for my colleagues and such to see how I really live and as a consequence, who I really am? I don’t know. Does seeing all the clothes I own and all my knick knacks hurt how I’m seen professionally? It’s funny that we’ve been doing this for a year now and I’m still questioning how to navigate being a person on Zoom every day.

EK: There are so many hierarchies in place just in terms of how we interact with other humans, but my students now have this window into where I live. They can see the little back house I live in and all the cat hair or whatever. So I think there’s a kind of humanizing that happens in one sense. I think the institution and the studio and the classroom all give power to the instructor, kind of like a shield or something. And suddenly that’s gone, that physical infrastructure is gone. There’s something kind of revealing about that.

AW: Now you’re just an ordinary person, like your students.

TL: Right. I think there’s also something about the time thing that is interesting. That is kind of horrifying that you have to respond to an email within a timeframe, but there is this reality that we’re all on all the time because we’re not going somewhere to do our work. It’s harder to know when work starts and finishes. One of the things that I’m seeing in the classroom is that more of the students seem to be doing more of the reading, and I suspect that’s because they’re just in this one room all the time and so they might as well read, whereas before they were having a fuller life and there was maybe less time to do that.

FC: I think timing is really important, and knowing when to pounce. I feel like the book pounced at the right time after East of Borneo has been quite sleepy for a little while. Ever since you arrived, Adriana, it’s been taking off and the book is pouncing on this powerful opportunity. Maybe there’s a sleepy time, but then you just have to harness time and do something incredibly powerful and emotional when it strikes.

I guess recently I’ve been worrying a lot about art and the space that it might hold in society. Like, is it going to be enjoyed or what? And then I realize, it’s going to fight its own fight because it’s powerful and engages people. I guess what I’m saying is art has a way of finding cracks and doing something beyond anybody’s expectations. Something I’m finding that I have to teach my undergrad students is that they’re making work for others as much as themselves. So, the bulletin boards are essentially support structures. There are things that are in a space that passively absorb and actively elevate messages and things. They’re social and they’re supportive. Remembering that we’re trying to teach this is a challenge at the moment, but I also have faith that it’ll come through.

Janet Owen Driggs: I think the moment may have passed, but I wanted to think more about the notion of intimacy and professionalism and how they have moved in the digital space of my teaching. I teach at a community college, so there’s a number of essential differences to teaching. I wrote the emails that were included in the book, which were full of concern and stress. I was working, like so many others, 70 or 80 hours a week, 24/7. It was crazy and has subsequently calmed down. But beyond that I’ve begun to experience moments of great intimacy with my students. Many of them have suffered from extreme stress during this time. They’re working full-time. They have family members that they care for. They’re also doing, or trying to have, a full-time load at school because the economic situation is such that they need to get through it as quickly as possible. But they’re finding that stress very difficult to cope with. So one of the reasons, of course, for working those very long hours is to provide support, support as an academic guiding them through academic processes—I teach art history, by the way. It’s also practical support, trying to find them ways to access the internet when all the coffee shops shut down and they don’t have it at home, or in some cases trying to get them mental health care or housing help.

So, I got to know my students in ways and with a degree of intimacy that I hadn’t before, and that’s possible because of digital technology in this circumstance. But what that also did—and this is also related to the murder of George Floyd—working in this manner has developed a more human relationship with my students and with my fellow faculty and staff. I was introduced to the notion that academic rigor is a product of white supremacy, and this is something that has informed my practice as a teacher. This is an idea I’ve been able to bring into my community, my college community, and which other faculty have brought into their college communities. And we’re really exploring notions of equitable grading. I don’t know how grading might work at Otis and CalArts, but certainly in the community college system grading is an incredibly important factor for the students. So how do we introduce equitable grading? How does that work with professionalism? These are all questions that we’re grappling with as an institution. Anyway, that was what came to mind at this correlation of intimacy and professionalism that came up in the conversation.

EK: Thank you so much for sharing that, and also for your contribution to the book, because I know it was an extremely difficult time to ask people to pause the active work with students that was occurring and try to then send something to me. I am really grateful and honored to have your email correspondence in the book because I think we actually open with it. And you acknowledge in the text that it’s an imperfect correspondence, that it’s maybe not even a professional correspondence. It’s written and sent in the seconds before you pass out from exhaustion from teaching 24/7. There’s intimacy in that. And further with this idea of academic rigor, and what Tom was saying about students having more time to read, I think with all that comes the responsibility of the classroom or the educator to say, well, just because the student has the time to read the assignment now, do I actually want them to spend that time reading? What other living needs to occur in this—I want to say “free time,” but what I mean is time outside of the classroom. And how do I forefront this idea of trying to slow down, and trying to acknowledge student needs holistically as human beings? I think the pressure of grading and what that protocol looks like over Zoom is really interesting. We’re starting to try self-assessment rubrics for students that are more geared toward how much growth a student perceives in themselves. We’re trying to basically reassess how we grade, and I think it’s a big, huge conversation that I would love to continue to have with you and anyone else.

JOD: It’s definitely a long and ongoing conversation and one that my college is embracing. But there’s a lot of pushback. I’d love to talk about specific techniques at some future date.

Nina Waisman: I was thinking about Tom’s question and the crazy 48-hour time frame given for answering an email. And then together with Janet’s comment, it’s great pointing out white supremacy and academic rigor. I wondered if any of you had managed to play with time. Is there any room to play with time? On the one hand, Janet, you’re describing how the students don’t have time to breathe, let alone maybe play with time. But there is this weird recurrence, for instance with the murder of George Floyd, when we really start to feel like we’re in this circular time of another murder and then another murder. So, the two questions of time and of grading just stand out I think.

EK: I mean, I’m by no means an authority on this, but one thing I’ve been thinking about is basically, how do we value students? How do we value time in terms of learning? What does learning look like in terms of its relationship to the time of class, to the time of the institution, to the length of a degree program? There are all these ways that it becomes, for me, about how a student’s time is best spent. How do they best spend their time to learn?

I think the default model is to try to fill their time with activities that seem productive and that produce deliverables with gradable outcomes. But I think the really difficult question for institutions and administrators and accreditation panels is: how do you acknowledge and value the time that doesn’t actually produce anything immediately concrete? How do you value the learning that might not manifest as a deliverable until five years down the line? And how do we as educators try to stretch, play, and challenge the kind of immediacy of institutional time in the way that we need to if we really are serious about the time to think and the time to learn? That’s just an initial thought. I’m sure other people have things.

FC: Adriana, I want to hear what you think about that, because your introduction in the book is incredible. I think the question you posed is awesome in regard to thinking about elongated time and deliverables. And you included a diagram.

AW: Thank you for reminding me. I think I was just trying to think through the difference between “learning” and “education,” the words themselves and the meaning those words carry. An education seems to me like a system in which we place capital, monetary value on learning. If you have an MFA, you are a more valuable artist. You are a more valuable thinker and a more valuable intellectual and you are literally buying into a system that vaguely promises to make you more legitimate as an artist, although I don’t think that everyone necessarily enters into an MFA program for that reason or thinks about it that way. But for me, I was thinking about it that way because that’s how I was trained throughout my entire educational experience, from kindergarten through graduate school, to understand what my degrees meant. I think that’s a completely different thing than actual learning, and what learning can be and what teaching can be, which are both things that I think should be kept separate from that value system that’s in place. And I think we’ve touched upon that question a lot during this conversation and this has been great.

I think it’s probably about time to start wrapping up, so I want to thank you all for coming and for sharing your thoughts and listening, especially now. Does anyone have any last minute thoughts they want to chime in?

EK: I just want to say this is the first time my mom has been able to come to anything I’ve done during my career in America, ever. I don’t know if she’s actually listening. She may just be asleep, but I can see her little iPhone on the Zoom call. And yes, she is still there, so that was quite exciting for me.

Teresa Kemp: Mother is still here.

EK: Thank you! It’s just really cool because, in one sense, we were talking about vulnerability and intimacy in real life. My parents have never come to anything since I’ve been teaching or since I’ve had an MFA because this whole experience, for me, has been in the U.S. and they’re not in this country. So this is the first interaction they’ve had with my work and that’s pretty incredible.

AW: My dad is here, too. Hi, Dad.

Curt Widdoes: Hi there!

AW: Hi. Thank you for coming. I think Tom has “left the building,” probably a connectivity issue, so I think if no one has anything else to add now is the time to end.

EK: Thank you, everyone! Thank you, East of Borneo. Thank you, Adriana. Thank you, Fiona.

AW: And I encourage you all to download the digital book. We know that everyone can’t afford to spend money on an art book right now, so we’ve made it available in alternative formats. Download it. Share it. It’s on our website.

EK: Yes, and if anyone wants ongoing conversation, please email me or something because I would love to keep talking about this. The book is meant to be a snapshot of a moment and to continue conversation, so there’s lots of exciting ways to move forward.

AW: Thank you! Have a great Saturday. Bye bye. I guess I’ll end by that.