RMS, 1944–45: Bethlehem Baptist Church

by Susan Morgan

Bethlehem Baptist Church in 2011. Photo: Carol Highsmith / Library of Congress

It is a dream time for working. You work at whatever you like. Now you can choose. There is only one requirement: that you work hard and steadily. But you can widen your horizon to take in whatever you like. And the beautiful thing is that you can do more than you know how to do, because the need is great. Flexibility of mind and an adjustable intelligence is all you need.

—Esther McCoy, unpublished story c. 19441

In 1944, architect R. M. Schindler began work on the Bethlehem Baptist Church, one of his few public projects and his only completed commissioned church.2 Bethlehem Baptist, established in 1933, was an African American congregation, five hundred members strong and housed in the former German Methodist Immanuel Church, built in 1909.3 When their original one-room church was destroyed in a 1943 fire, the Baptist congregants decided to build anew on the same South Compton Avenue site.4

As Eric Brightwell, a twenty-first century cartographer/urban explorer and shrewd observer has remarked: “South Central is to South Los Angeles as the Bible is to most bookshelves. Everyone thinks that they know its contents and yet few have actually bothered to crack it open.”5 South Central, he points out, was named for its high street, South Central Avenue, and already referred to as Los Angeles’s “black belt” by 1915 in the California Eagle, the longest -running of the city’s three Black-owned newspapers. Before freeways circled and ensnared the area, Bethlehem Baptist Church fit assuredly within its South Park neighborhood. Just under a mile away was the recently completed Pueblo del Rio (1941–42), public housing conceived according to the progressive “garden cities” plan and designed by chief architect Paul Revere Williams, working with Richard J. Neutra and others.6 The local high school, built in the aftermath of the Long Beach Earthquake and designed by Stiles O. Clements, and the Fox Gentry Theatre, a one-thousand-seat movie palace (S. Charles Lee, 1938) were both casebook studies in Streamline Moderne, sporting flowing horizontal lines and the occasional porthole or pylon added for flair.7 On nearby Central Avenue were the offices of the California Eagle, published and edited by the indomitable Charlotta Bass; the Dunbar Hotel, opened in 1928 to host the NAACP’s national convention; and Club Alabam, recognized as the epicenter of the 1940s jazz scene. At Bethlehem Baptist, Dixie Milton served as chair of the church’s General Committee while her husband, Roy, a popular rhythm-and-blues bandleader, played the Avenue clubs and Sunset Boulevard lounges. Roy Milton and his Solid Senders were a sharply dressed six-piece combo with Camille Howard on piano; their sultry “R. M. Blues,” recorded in December 1945, went on to top the hit parade for twenty-five weeks.8

Left: Roy Milton (bottom right) and his Solid Senders, featuring Camille Howard on piano. Right: R. M. Blues, 1945, as reissued by Milton on his eponymous label, with artwork by William ‘Alex’ Alexander.

Accounts of 1940s Los Angeles veer inexorably between the era’s contradictory events and attitudes, urban expansion, economic opportunities, legislated racism, and social upheaval. South Central, within City Council District 9, was represented by Parley Parker Christensen, a member of socialist writer Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC) movement. Political activist/journalist Carey McWilliams (a tenant in the Schindler-designed Falk Apartments during 1944) published Prejudice: Japanese-Americans: Symbols of Racial Intolerance, while Theodore Dreiser touted LA’s evolution as a “new kind of world city” generating cultural change.9 Schindler published “THE ARCHITECT-POSTWAR-POST EVERYBODY,” a fervent open letter in Pencil Points (“a journal for the drafting room”), and declared that it was the architect’s responsibility to work prudently and consider the financial, structural, and spiritual aspects of each undertaking. “He [the architect] must understand the owner and the neighborhood sufficiently to make his design an asset to both,” Schindler stated. “He must sense the meaning of life and have a vision of its future. His imagination must enable him to take a pile of building materials and create an organism which will function and live.”10 In his design brief (typed single-space, in all capital letters) for the Bethlehem Baptist Church, Schindler outlined an architectural scheme that emphasized generous use of a difficult corner lot, dynamic connections between indoor and outdoor social spaces, and attention to issues of light and sound. “THE TOWER,” he went on to explain, “IS SHAPED LIKE A CROSS IN BOTH PLAN AND ELEVATION. HOWEVER, INSTEAD OF RETAINING THE TRADITIONAL SYMBOL OF AGONY, IT HAS BECOME FOUR DIMENSIONAL AND WITH OUTSTRETCHED ARMS IT INVITES THE CONGREGATION TO GATHER UNDER ITS SHADOW. FOUR LOUD SPEAKERS AT THE BASE OF THE CROSS ALLOW FOR THE SOUNDING OF CHIMES AND SONGS, AND OUTDOOR SERVICES.” As architectural historians have since pointed out, the open cruciform tower serves as a sort of billboard, “a Christian advertising sign” large and clear enough to be read by passing motorists.11

In 1944, when Esther McCoy went to work as a draftsman in Schindler’s office, she found the plans for the Bethlehem Baptist Church on her board and was suddenly tasked with drawing in details, such as symbols for the placement of electrical outlets and metal flashing around the rooftop cross. A literary writer lately employed as a draftsman, she’d lived and worked in New York, Paris, and Key West during the 1920s. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, she moved to Los Angeles. As critic Jed Perl has astutely noted: “McCoy was very much product of the 1930s … [and] in the deep background of all her work is that decade’s combustible mix of Marxism and modernism.”12 In California, she configured the piecemeal livelihood of a freelancer: assisting civil liberties attorney Leo Gallagher in his defense of incarcerated union activist Tom Mooney, producing surveys on slum clearances, co-authoring pseudonymously published detective novels, and contributing unsigned stories to publications as varied as Upton Sinclair’s socialist EPIC News and glossy fashion magazines. At the end of 1941, when the United States entered the war, she trained as an engineering draftsman and went to work for Douglas Aircraft.

“Nowhere was the break with the past more evident than in the aircraft industry, a creation of World War II,” McCoy later observed. In Southern California, the aviation business was transformed from a handful of companies staffed by white men to the region’s largest industry, employing a work force that was suddenly diverse in gender, race, age, and professional experience. This newly expanded labor pool included WWI veterans, resourceful women, and matriculating students and operated in three shifts around the clock. By the autumn of 1942, Douglas Aircraft plants located throughout Los Angeles County employed more people than all of the Hollywood studios put together. At the Santa Monica facility, the drafting room was two city blocks long: blueprint girls on roller skates expedited plans, hot meals were served on site, and twelve thousand free Eskimo Pie ice creams were distributed at break time.13 McCoy’s husband, Berkeley Greene Tobey—a dapper New Englander twenty-three years her senior and a key figure in New York’s early avant-garde literary and socialist circles—manned the ice cream trolley.14 Among McCoy’s fellow Douglas employees were William S. Becket, recently graduated from Yale School of Architecture; established LA architect James H. Garrott, whose projects within his community included the 1928 Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Building, one of the most successful African American–owned businesses in the West; and Rodney Walker, a designer/builder with an interest in low-cost housing.

Left: Esther McCoy at her drafting board, Santa Monica, c. 1945, Esther McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Right: The C-74 Globemaster at Douglas Aircraft in 1945.

When the demands of wartime production eased up a bit, many of the young draftsmen and engineers at Douglas began to design houses envisioned for themselves. At home, McCoy set up a drafting board by her typewriter and studied architectural drawings given to her by Walker, one of her bosses at Douglas and a former draftsman in R. M. Schindler’s office. Although McCoy and Tobey’s own home was a turn-of-the-century bungalow in Ocean Park, they were closely acquainted with modern domestic architecture: Harwell Hamilton Harris’s Entenza House (1937–38) had been built for their friend, editor John Entenza; and another friend, drama critic Byron Pumphrey, lived nearby in a 1939 Harris house that featured Frank Lloyd Wright influences.15

In 1938, when prolific author and erratic socialist Theodore Dreiser settled permanently in West Hollywood, McCoy was able to revive one of her earlier New York gigs, working part-time as his researcher. Dreiser’s traditional house on North Kings Road was in the Spanish Mission style—white stucco walls, red tile roof—but its immediate neighbors were two absolute landmarks of modern architecture: the Walter L. Dodge House (Irving Gill, 1916) and the Schindler House (R. M. Schindler, 1922).16 Through a mutual friend and their shared involvement with leftist politics, McCoy and Tobey had met Pauline Gibling Schindler, the architect’s estranged wife and ardent champion, who was residing in the north studio of the divided house. Their introduction to Schindler’s house, however fascinating, was somewhat puzzling. “In that Puritan period of modern design, this house was mysterious and disturbing,” McCoy admitted. “With the floor on the same plane as the hearth, and the hearth on the same plane as the patio, fire joined earth. And wind—through open sliding doors were east and south breezes. What Pauline said about the house was poetic, but to someone who had worked so recently with .032 Alclad at Douglas, I was concerned with weight and with how things were put together. So the Kings Road house was a closed world.”

R. M. Schindler’s architectural practice had always been small, sporadically staffed by friends, enthusiasts, and recent students often hired on a project-to-project basis.17 Gregory Ain, for example, estimated that he’d been employed there for about six weeks in the 1930s; Zelma Wilson, the only woman graduate in USC School of Architecture’s class of ’47, interned during the summer of 1942; and Abraham Columbus frequently carpentered Schindler-designed furniture for Samuel and Harriet Freeman, as well as making cabinetry for other less-perennial clients.18 Architect E. Richard Lind was perhaps the steadiest employee, starting in 1933 and spending nearly ten years in the Kings Road office. When he was recruited by the US military to engage in “secret war work,” he left for good and conveyed his earnest thanks to Schindler. “I can say this most sincerely,” he wrote. “I consider my most valued training with you in learning how to live which after all is architecture.”19 With Lind gone, the office was without a draftsman and Pauline Schindler suggested McCoy apply for the job.

McCoy did apply, was hired, and went to work in Schindler’s office on the south side of the divided house. Starting work there each day at 11:00 am, she wrote at home in the mornings and continued to take on occasional assignments for Dreiser. Her curiosity, the questions she had about Schindler’s architectural intentions and seemingly improvisational methods, were addressed on a daily basis; answers and understanding might eventually surface through persistent observation, direct inquiry, nagging reconsiderations, or regular hands-on work.

Although new construction and even home renovations were still hampered by war-related building restrictions, material shortages, and the high cost of professional plastering, Schindler—working with the cheapest materials, a constrained budget, and a narrow site—had managed to design a confident, exalted place of worship for the Baptist congregation. Clerestory windows and squares of glass set directly into the roof brought in daylight from above and the astonishing pinwheel-cross presented eight bold silhouettes to the outside world. McCoy quickly discovered that Schindler “simplified everything, even his files: he filed not by the twenty-six letters of the alphabet but by the vowels”; information about Bethlehem Baptist could be found under E. His complex design descisions were equally pared down and radically distinct. “To the end of his life,” remarked architectural historian Wayne Andrews in his appreciation of Schindler. “He fought against the impersonal gospel of Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe.”20

Like many of Schindler’s projects, the low budget for the church tilted toward insufficiency. Initial funding had been provided by the fire insurance claim, a savings account earmarked for future building, and donations. The Bethlehem Baptist congregation took a practical approach to their fundraising, targeting $25 and $50 pledges and accepting compromises and delays. Schindler calculated the final construction cost at $17,000. In 1945, a real-estate agent who served as a church deacon received a $40,000 offer for the property—presented by a speculator hoping to turn the Schindler-designed church into a nightclub.

McCoy recalled that by 1945, “when the strictness of International Style ruled design,” Schindler had been dismissed by the architectural profession and press as a once-promising talent who had lost his way. His more recent buildings were seldom written about or photographed; he was often disgruntled by the shortcomings of photographs and querulous with editors. In 1944, editor Marguerite Tjader Harris, publisher of the leftist cultural journal Direction, arrived from the East Coast to assist Dreiser with his neglected novel The Bulwark.21 McCoy, given the opportunity to write for Direction, contributed “Work for the Night is Coming”; a fictionalized memoir (its title taken from a nineteenth-century hymn), it was a story about women workers during World War II and the modern aircraft industry’s dramatic break with the recent past. When Mrs. Harris asked for a second piece about California, McCoy wrote about Schindler’s office, describing his concept for designing with volumetric space and praising the Bethlehem Baptist Church: “He has discarded all the clichés of ecclesiastical usage without on the other hand indulging in extraneous brilliant techniques. He simply made a gracious statement in wood and glass.”

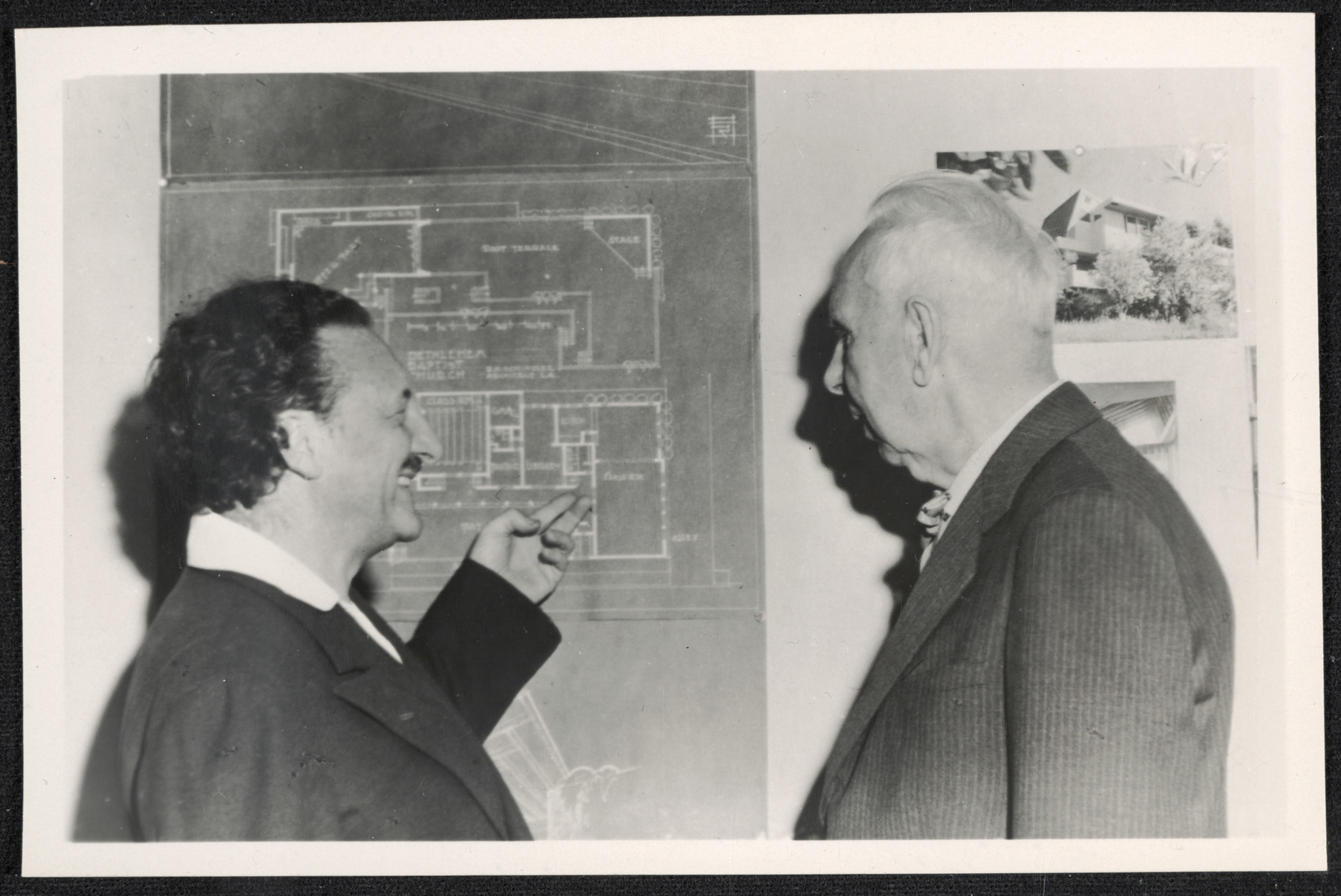

R. M. Schindler and Theodore Dreiser looking at a blueprint of the Bethlehem Baptist Church, 1945, photo by Berkeley Greene Tobey. Esther McCoy Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

In November 1945, McCoy and Tobey organized a Schindler exhibition for the Thomas Jefferson Book Shop Art Gallery in Santa Monica. Timed to coincide with the release of Direction 8, No. 1 (featuring McCoy’s article “Schindler: Space Architect”), the exhibition presented drawings, photographs, floor plans, and blueprints of Schindler’s work in California, starting with the 1920s and continuing straight through to the Bethlehem Baptist Church. Tobey, displaying innate good manners and years of experience with public relations and social good, sent an amiable note: “Your exhibit at the gallery has attracted many more interested visitors than any of our previous exhibits of paintings, and we want to thank you most heartily for allowing us to show examples of your architectural works.” Enclosed in the letter was a photograph of an ebullient Schindler pointing out plans for the church to his bemused-looking Kings Road neighbor.22 Dreiser and his wife, Helen Richardson, had been perturbed by Schindler’s studio and regarded the concrete floors, unpainted redwood, and sliding doors as inhospitable and potentially unhygienic; their view of twentieth-century design remained loyal to a more ornate craftsman tradition.23 At the gallery, Schindler also presented a public talk, “The House We Want,” illustrated with “color slides of modern houses and interiors.”24

The Thomas Jefferson Book Shop is cited in Berkeley Tobey’s FBI file as “a Communist-owned bookstore,” a front distributing literature to comrades in the Bay Cities. The gallery was generally curated through an open-call viewing program; the shop was staffed by a manager and a few volunteers including Tobey and Mrs. Moiselle Clinger, a West Hollywood housewife. From 1942 until 1956, while employed at Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica and helping out at the bookshop, Mrs. Clinger worked as an undercover agent reporting weekly to the FBI, doggedly fueling the Red Scare.25 Another FBI informant working in Dreiser’s household referred insolently to the author as “a has-been,” officially reporting that he did “very little writing and what little work he does put out is not in great demand by publishers.”26 The bookshop newsletter announcing Schindler’s exhibition, however, conveys a rather unclouded sense of cultural optimism, no hint of paranoia or un-American activities: Frank Lloyd Wright’s When Democracy Builds and the catalogue for Built in USA, 1932–1944 (Elizabeth Mock, MoMA) are new and recommended titles, Christmas cards designed by Rockwell Kent and Vladimir Bobri are on sale, and Adelaide Fogg will present “Works of Art For Children.”

Bethlehem Baptist Church in 2011, photo by Cbl62, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Bethlehem Baptist Church, a rare project for Schindler and a significant contribution to the legacy of Los Angeles modernism, was slow to be noted by any publication.27 When Julius Shulman photographed the church in 1949, Schindler rejected a group of images (“NONE OF THESE ACCEPTED/BILL NOT DUE”), demanded retouching, and paid for only the photos he deemed acceptable. Douglas Haskell, editor of Architectural Forum, sent a plaintive note asking the architect when he might see “plans and pictures of your little church”; in September 1949, the magazine decided to publish the church “as is” and defaulted on offers to retouch Shulman’s photographs. Ebony published the church in 1951 and jubilantly proclaimed “West Coast Congregation Worships in Futuristic Edifice.”

After leaving Schindler’s office in 1947, McCoy continued in her efforts to have his work recognized. Following his death in 1953, she received a letter from urban planner Lewis Mumford, architecture critic for The New Yorker. “I am sorry to hear about Schindler’s death,” he wrote. “He kept the ball in the air at a time when few were capable of kicking it along the ground.” Clearly, they both recognized that Schindler was, as they used to say in the 1940s Central Avenue jazz scene, “a solid sender”—no pretender, an inspiration who could send your spirits soaring.