Second Life: 4 Taxis Magazine

by Thomas Lawson

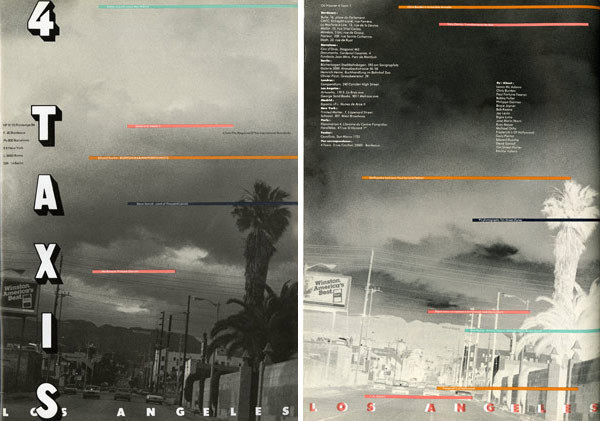

Cover of the Los Angeles issue of 4 Taxis, No. 9/10, Spring 1984. All images courtesy of Michel Aphesbero and Danielle Colomine unless otherwise noted. To download a PDF of the full issue, click here.

During the spring of 1979, Susan Morgan and I had just published the first issue of REALLIFE Magazine when a mutual acquaintance introduced us to Michel Aphesbero and Danielle Colomine. Dani and Michel were in New York, visiting from Bordeaux, to work on an issue of their magazine, 4 Taxis. The introduction was made so that the four of us, publishers of two distinct but similar small art magazines, could compare notes and talk. Susan and I were interested in giving voice to a particular generation of younger artists living and working in Lower Manhattan, and generating a context that would eventually grow to Los Angeles and then further afield. Dani and Michel were also interested in exploring this space between extreme locality and the wider world, and we found many of the same artists interesting. So we have been talking off and on, in New York, Los Angeles, and Bordeaux, ever since. This conversation was conducted in an abstract space, over the Internet, and over extended meals in these real, shared places.

THOMAS LAWSON: Let’s start with some background information. Can you say a little bit about how you started 4 Taxis—when, why, and how?

MICHEL APHESBERO AND DANIELLE COLOMINE / 4 TAXIS: You forgot “where”! 4 Taxis started in 1978 in Bordeaux, where we lived and which is still our port d’attache [or home base]. It was meant to be a place of convergence for artists’ works done especially for the magazine, coming from four cities: Bordeaux, Barcelona, Roma, and New York. To escape our Bordeaux boredom, we used the magazine format as an artist’s project enacting our desire to leave. We suffered from dromomania, or the uncontrollable psychological urge to wander. But when does traveling become pathological? Ian Hacking tackles this question in his book entitled Mad Travellers, which talks about dromomania and tells the story of Albert Dadas (1860–?), the first runaway maniac in the real epidemic of insane travelers, which spread all over Europe at the end of the 19th century, and of which Bordeaux was the epicenter. This story inspired us to do a photo novel in 2004, so you can see our obsession with pathological traveling has not waned.1

The first issue of 4 Taxis acted as a kind of tool to go to New York and meet people. We had been very impressed by a special issue of Art-Rite directed by Alan Suicide (aka Alan Vega). We definitely wanted to meet the artist and the publishers, Edit deAk and Walter Robinson. Christian Boltanski (who was then teaching at École des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux with Annette Messager) had given us an old copy of Art Diary so we could find their addresses. We met a lot of artists, without knowing their names, at Edit’s Wooster Street loft. With Edit, we planned our second issue, 4 Taxis “Parfum de New York” [no.2], which was to feature the work of New York artists. She sent us works by Pat Place, Peter Grass, Italo Scanga, Mike Robinson, Steve Gianakos, and Jimmy de Sana.

This trip also generated our first encounter with the Printed Matter bookstore, which was on Lispenard Street in those days. While in New York, we met Antoni Muntadas and developed some new material for a fiction piece about a Barcelona bookstore keeper–murderer that was to be published in the following issue, the first one to have a theme: “Mystery Novel” [no.3/4].

At that time, readers thought that this editorial topic of roman noir [“black novel”] dealing with the four cities’ artists’ works would be the permanent focus of the magazine, but when they received the following issue called “Cover Issue (Waiting for Your Taxi Which Taxi Never Comes)” [no.5], they were really confused! It was a homemade conceptual artwork. Ninety-four percent of the magazine was blank space, with only a few pictures; the centerfold was a reduced picture of Der Spiegel’s Joseph Beuys cover with staples right through the eyes and the mouth.2

In the 1980s, the magazine got more radical, the motion physical. Danielle left for Berlin in 1980 in an old Renault 4L, beige with a green door, with an artist’s grant and a new objective: to live in a foreign city for six months to one year, and to conceive there an artwork with the city as its topic, the magazine as its form. We were asking the question, “How do we integrate art into our own lives and other people’s?” Right from the start, the meetings in Berlin with Martin Kippenberger and his crowd—which ranged from the gang of Austrian artists-restaurateurs Michel Würthle and Oswald Wiener, to the punk scene, Einstürzende Neubauten, Die Tödliche Doris via Tabea Blumenschein, Michael Krebber, and Gisela Capitain—jammed all classifications.

In 1983, we published a special head-to-tail edition called 4 Taxis “Perpendiculaire,” (series of 2) based on the idea of a monographic collision of peculiar people or subjects. It had a Kippenberger-Dokoupil work, Homme Atelier Peinture à Cologne (1983), on one side, and a feature on the Lascaux caves on the other side.

That’s where we come from, you know—the caves! Danielle is from Tarbes, at the foot of the Pyrenees, near the grotto of Lourdes. Michel comes from Mauzac, a village in the Dordogne near the Lascaux caves. Bordeaux is our meeting point,

somewhere in between. We move on, still holding this background with us—it’s the boondocks we recognize elsewhere.

TL: That is a word you return to often: boondocks; often prefaced by the adjective “international” as if to give it more weight, and so more humor. What are the “international boondocks”? Where are they to be found?

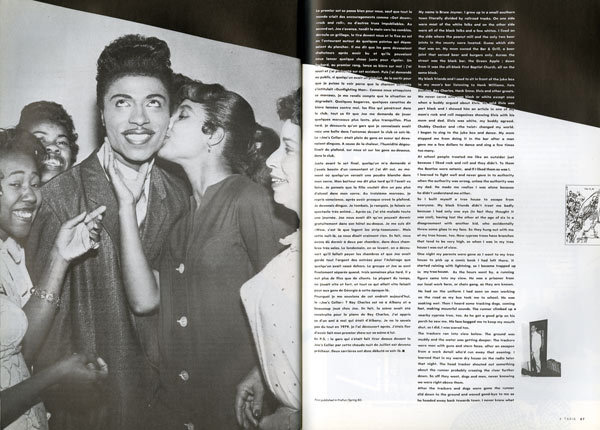

Little Richard, in an essay by Bruce Joyner of the LA-based band The Unknowns and Bruce Joyner and the Plantations, “Way Down South in Dixie,” 4 Taxis no. 9/10, Spring 1984.

4T: They are deep down in any of us, when you feel in some way “out of it.” The international boondocks are in your head, not only in a geographic situation. They represent the idea of “whatever singularity.” This sounds like an oxymoron, but they represent a relationship to the world of multiple belonging. International and vernacular, the cambrousse internationale refers to the idea of ultra-local.

TL: The Los Angeles issue that you published in 1984 (no.9/10) is a very complete expression of this combination of extremely local content, evidence of very specific knowledge of particular subcultures in the city along with a broader, European take. It is quite a feat of embedded reporting. When did you arrive in Los Angeles, and how long did you stay in the city?

4T: Danielle arrived in LA in the summer of 1982 and stayed for one year. She found a job as an art teacher at the Lycée Français, lived in Hollywood, and worked in Redondo Beach—driving every day back and forth between the north and south of the city in a Volkswagen with a Harley Davidson muffler. Michel came over for six months. We lived in the heart of Hollywood, on Carlton Way, the same street where Bukowski had lived, just a few minutes from Cathay de Grande and from the punk scene. We were right in between X and PIX, the two porn cinemas with neon signs that lit the east and west windows of the house. When we settled there, the PIX was showing El Taxista Asesinado. They have both closed down by now, one painted white and bricked up, the other converted into a Salvation Army.

TL: The issue gives a remarkable snapshot of Los Angeles in 1983. Who was your guide, and how did you learn to navigate it so quickly?

4T: The idea to do an issue was perfectly clear from the start. Danielle went to LA with, as a first clue, an article by Philippe Garnier, a French journalist who wrote for Libération and who had also translated the writings of Fante, Bukowski, James Crumley, and others. He lived in LA, and his articles dealt with the music scene, the daily life, food, and his neighborhood between Silver Lake and Echo Park. And we arrived carrying all the mythologies of the city as we knew them in Bordeaux. We knew we wanted to meet the Cramps, Edward Ruscha, and Russ Meyer, and to dust off Eddie Cochran’s grave.

It was, first of all, an everyday adventure. How to achieve this feat: to go fast and slow at the same time? With what compass? We would grope along, the light would hurt our eyes—the city exposed itself like a huge studio with open freeways, a paradoxically friendly and unwelcoming landscape where the bank clerk calls you by your first name. Or where this guy on Vine Street, ever peaceful, stops the traffic, kisses the asphalt, and then moves on.

Our tools were intuition, nerve, and clumsiness: walking, driving, meeting people, and reading newspapers. Philippe Garnier became a friend. His outstanding chronicles of LA and his posture of loquacious maverick nurtured our excitement every day.

We met Steve Samiof in his gallery, Steve’s House of Fine Arts (SHOFA), at the corner of North Larchmont and Melrose. It was cool inside, a gallery governed by the creed “quality art priced to move.” Structured as a series of two-night exhibitions that were basically parties, SHOFA showcased work by such local talents as Ruscha, Gary Panter, Mary Woronov, and Matt Groening. Steve was 33 and had already moved 66 times in Los Angeles! A plumber’s apprentice/stage designer/florist/car dealer/publisher of the punk magazines Slash and Stuff, he would show newcomers around the city on his motorbike.4

He was a master of “making as knowing” and a sharp analyst of LA scenes. “To me, a scene is 20 people who work together in an auto repair shop,” he’d say. And then there was his attachment to the story of rock ’n’ roll in the 1950s, which resonated with us since Michel had created his own Buddy Holly fan club in the Dordogne when he was 15. This lifelong fandom continued in LA, and we arranged to have meetings with Bob Keane, the early producer of Sam Cooke, Bobby Fuller, Ritchie Valens, and Frank Zappa. This flood of names ended up in the contents of the LA issue.

TL: Is there a thread connecting your interest in Steve Samiof of Slash, Gary Panter, and the editors of the LA Weekly?

4T: Yes—a love of printed matter and Corona beer! Steve and Gary lived in our neighborhood, and LA Weekly—in Jay Levin’s [the Weekly’s editor and founder] days at 5325 Sunset—was also not far from our place. As parallel guides, we would read the comic strips by Gary, Matt Groening, Mike Kelley, and David Lynch, which were published in the two free newspapers, the LA Weekly and The Reader [now defunct].5

TL: You cover art, of course, but also music, movies, popular culture, and, interestingly, other publications. Did you see these subjects as interconnected in some way?

4T: That’s still our daily exercise, and it is inscribed in the magazine’s project. But the most thrilling part is how these interconnections are revealed. Take the LA issue, for example: The cover features a picture taken through the windshield on the way back from work, along Gower Street. It’s a banal, everyday sight. The Hollywood sign is hardly visible, clinging to the hills in the same tiny type size that announces the magazine’s topics to the reader. The idea of visual fatigue pervades the whole.

The entire issue unfolds like a script—and that competition is hard in LA! The first pages are a double spread with a picture of Joshua Tree and its High Desert Cultural Center. Then along comes a coyote crossing a freeway, to illustrate the story of a baby that was devoured by a coyote in Glendale. A few pages later, we are in the bar of the Nickodell restaurant, close to Paramount Studios, with Russ Meyer, for a king-size interview in pidgin English. The Catalan connection gets moving again with [the Spanish film director] Bigas Luna, who had just finished Reborn with Dennis Hopper and revisits the difficulties and misunderstandings of European filmmakers who want to work in Hollywood. The interview with Ruscha connects and binds (in the bookbinder’s sense) all of the topics: architecture, music, painting, typography—and he also produces an original piece for the issue.

The Gary Panter, Steve Samiof, Chris Burden, Ritchie Valens, LA Weekly, Philippe Garnier sequences summon a fragmented cartography. The visual discrepancies and the assemblage of dissonant fonts (Futura and Fraktur Gothic, both quite banal by now but not at the time) attempt to bring out the aesthetic essence of the city at hand.

TL: Ruscha was already a well-known artist then. How did you persuade him to do a piece for you?

4T: Our force of conviction! [laughs] Our mainspring was a mixture of provincial shyness and nerve, and he soon understood the idea of the magazine. We interviewed him in his studio on Western Avenue, and we talked about country and western music, typography, architecture, and about the way to move and to stay in LA. The fact that he made a specific piece for 4 Taxis was fantastic! He also taught us a new word: fickle. Another word without scale.

Ed Ruscha’s “Special Project” for 4 Taxis‘ LA Issue. © Ed Ruscha. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. This image is a scan of an archival copy of 4 Taxis; the guttering effect is from the journal itself, and not part of Mr. Ruscha’s original artwork.

TL: Scale is interesting as it works throughout the issue—the use of small type, discordant type; the introductory gambit of framing the big city of Los Angeles and its urban myths with an image of the decidedly small-town culture of Joshua Tree; the rhyming, overarticulated eroticism of Russ Meyer’s fixation on large breasts and the lingerie at Frederick’s of Hollywood, both played out in extensive interviews.

4T: Maybe it is about the plainness of desire, interconnected with the relief of forms.

TL: Can you talk a little more about design back then? This issue was put together before computer design software made it relatively easy to cut and layer text and images.

4T: It was made in 1983. Graphic design was already about deconstruction even if Emigre magazine wasn’t yet born. They mentioned our LA issue in their 10th-anniversary album as one of their inspirations. Without a Macintosh computer or layout software, we took part in every stage of the production, getting our hands dirty. Our mouse was the cutter, and our enemy was dust!

The interviews, the photos, the tapes and transcriptions (by Michel’s sister, Françoise Aphesbero, who dealt with miles of translations), the layout sketches, the pieces of photo setting pasted on graduated paper, the camera-ready paste-up, the plate exposure, and all the nights at the printer’s shop in Bordeaux, were pure moments of R ’n’ R. Not to mention the minute issues of distribution and consignment in bookshops. The whole process involved a chain of relationships and discussions that have now been compressed by the digital and, sometimes, loneliness.

Then the following issues became very different objects. 4 Taxis “Fads” [no.11] was set up with pages coming from various countries, unstapled, cut up, dragged around in our pockets, orphaned, and then gathered in the magazine. Our Sevilla issue, titled “One Year in Sevilla Forever,” took the shape of a perpetual ephemeral calendar, with 365 pages, black and white, to tear out; like a folkloric vision of eternity.

To download the full issue of 4 Taxis No. 9/10, Los Angeles (1984), which features contributions by Ed Ruscha, Tim Street-Porter, Gary Panter, and Chris Burden among others, click here.