Senga Nengudi’s “Ceremony for Freeway Fets” and Other Los Angeles Collaborations

by Nick Stillman

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, March 1978. All Nengudi images courtesy of African American Performance Art Archive and copyright of the artist.

Probably like most who are aware of her art, I’m an admirer of Senga Nengudi’s great RSVP series from the late 1970s. These unforgettable installations of pantyhose fabric filled nearly to the breaking point with sand and dirt work in so many directions: as juxtapositions of the endurance of the natural and the tenuousness of the synthetic; as references to sex, pregnancy, or functioning inner organs; as a beautiful visual articulation of some type of abstract fetishism. But for all the celebration of the RSVP installations as scrappier takes on formlessness in the manner of Louise Bourgeois and Lynda Benglis⎯and heavily filtered through assemblage art’s employment of freighted materials with a past life⎯it isn’t easy to find out much more about Nengudi’s other work.1

On October 2, the Hammer Museum opened Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980, thus focusing new attention on Nengudi and others who comprise two nearly invisible classes of artists: postwar LA artists whose work isn’t grounded in Pop or Minimalism, and conceptual African American artists who precede the rise of multicultural studies in the late 1980s. If there is one event that undeniably shaped local black artistic, intellectual, and activist work during this period, it is the 1965 Watts Riots, a six-day surge of fury against economic oppression and racist police tactics that was maybe the most acute consciousness-raising event for black cultural action in America since the years of the Harlem Renaissance. If the subconscious of the Harlem Renaissance was about the possibility of integration, though, the Watts Riots and subsequent visibility of the Black Panthers in California showed a very different vision of black cultural empowerment: one grounded in the knowledge that socioeconomic parity wasn’t going to just happen.

There’s a stunning Los Angeles Times photo taken in the aftermath of the riots, of a block in Watts that had been reduced to a tangle of steel and brick.2One building stands so tenuously that the signage affixed to the exterior threatens to drag it earthward into the pile of rubble below. An elderly woman gapes in amazement; a cop car slinks past. The human toll of the riots is heavy in the image: the 34 dead, the 1,000-plus injured, the 3,000-plus arrested, the homes destroyed, the neighborhood’s economic infrastructure literally leveled. Nengudi’s most visceral memory of the Watts Riots is of National Guardsmen patrolling the streets while she walked her mother’s dog, even though they were a few neighborhoods away from Watts. Not long after the riots, she worked with artist Noah Purifoy at the Watts Towers Center, an experience that imprinted on her the importance of “breaking through the white cube and connecting with the rest of humanity.”3

Senga Nengudi, RSVP I, 1977. Nylon mesh, sand. Dimensions variable.

For Purifoy and other Watts-based artists who collected multiple tons of rubble from the razed neighborhood, the riots politicized their form of junk assemblage sculpture and make it necessary to consider how the Watts Riots functioned as an aesthetic event. Junk assemblage was inexpensive to make and suddenly laced with local significance. Watts assemblage definitely wasn’t “assemblage art” in the Rauschenberg-Kienholz vein, famously positioned in William Seitz’s 1961 MoMA exhibition “The Art of Assemblage” as a statement about the conditions of technocracy, consumer society, and alienation in post-1950s America.4The assemblage work being made in Watts spoke about true urban devastation and the glimmer of an opportunity for total reconstitution that is the strange companion to destruction. Los Angeles assemblage artist John Outterbridge has said of assemblage, “What is available to you is not mere material but the material and the essence of the political climate, the material in the debris of social issues.”5So assemblage became an index of collective experience and trauma, but one geared toward the local and suggestive of the functionality of African fetishes: to heal, create understanding, or promote group identification through objects.

It may be instructive to consider the entire Hammer exhibition from the viewpoint of ritual practice in postwar (and post-Watts) African American art, but this essay will be limited to Nengudi and a relatively obscure piece she made with the loosely wrought and constantly morphing Studio Z collective of artists she worked with in Los Angeles, which included David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Franklin Parker, Barbara McCullough, Houston Conwill, and Ulysses Jenkins. A few sources mention Nengudi’s first major public installation and performance from 1978—Freeway Fets, and the accompanying Ceremony for Freeway Fets—but without many details. What happened during the ceremony, why was it staged under the highway, and what exactly were the “fets”? These questions linger in part because of the lack of permanence characteristic of Nengudi’s work and of course inextricable from all performance art. The pieces used in the installation no longer exist, and a film that McCullough attempted to shoot of Ceremony for Freeway Fets “didn’t take,” so aside from oral histories, the only evidence of it is a dozen or so performance photos by Roderick “Kwaku” Young. And yet it seems like an important work in Nengudi’s oeuvre, one in which ritual and the connotations of rubble in Los Angeles become paramount.

Senga Nengudi, Freeway Fets, 1978. Installation, mixed media.

Ceremony for Freeway Fets was performed by Nengudi, Hammons, Hassinger, and others from Studio Z to a small crowd underneath a freeway overpass on Pico Boulevard near the Los Angeles Convention Center. There’s a juxtaposition between life and its struggle with infrastructural encroachment⎯the overgrown, undergroomed nature of the area and the clean-lined majesty of the freeway and its soaring support columns⎯that gives sites like these a particular gravity. The opportunity to use the location was, somewhat surprisingly, enabled by the city government. During the late 1970s, California’s state department of transportation (Caltrans) established a program to place art around freeways and along surface streets. Nengudi says she was drawn to that unexceptional patch of public land because the modest natural life persisting there⎯tiny palms and shrubs amid the dirt⎯“had the sense of Africa.”

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, March 1978.

In McCullough’s 1979 video, Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflections on Ritual Space, Nengudi says that she wanted to make the piece feel “like African fetishes,” or talismanic objects with undefined expressive power.6The RSVP installations are usually noted in this way for suggesting the female body, and not just by virtue of their bulbous, hanging swells; it’s well known that Nengudi hit on the idea for the pieces while pregnant. In Freeway Fets, Nengudi used her signature material to suggest the male anatomy as well. Using a crane to reach the tops of the highway columns, Nengudi tied a thin circle of pantyhose fabric around the circumference of the column, and from this fabric, she hung several densely clumped, multicolored forms, all quite diverse in shape and color. From afar, the clustered bunches look like a swarm of amorphous protuberances; from up close, they’re distinctly phallic, if flaccid, tubelets. Nengudi also installed a “feminine” counterpart: individual pantyhose sculptures draped from the tops of the columns, affixed to the same area where the “male” forms were grouped. These were roughly human scale, and, as described by the artist, swayed in the wind “like a grass skirt.” The dangling appendages are balled in several places, giving them the look of long beaded hair, as if an invisible Rapunzel were hiding under the highway.7

When Nengudi said that she wanted the visual elements of Freeway Fets to be “like fetishes,” I think she was referencing the relationship between the fetish object and ritual action: in this case, a performance, or ceremony, uniting the dual masculine-feminine energies that the installation hinges on. The performance was something like an improvisatory dance exercise, although its symbolism was pointed and specific. There was very little predetermined narrative and no rehearsal. It took place at the site of the installation. Hammons and Hassinger enacted the roles of male and female spirits. Nengudi designed their costumes and headdresses, as well as those for the Studio musicians who improvised a soundtrack. In typical Nengudi fashion, the headdresses were fabricated from pantyhose, echoing the installations nearby on the freeway supports. Hassinger wore a loose-fitting white cloak, and Hammons dressed in bright pink pants and carried a staff, the only visual element of the performance that wasn’t of Nengudi’s design. Wearing a white painter’s tarp and a mask, Nengudi played the unifying spirit between the opposing genders. She describes herself as feeling like another person upon donning the mask: “I just felt as if I was someone else. I was really practically possessed. I was in this rapture.”

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, March 1978.

Briefly, a word on pantyhose: as functional objects, we know what they do. As symbolic objects, they reinforce the disparity in power between genders. The zenith of the pantyhose era was the 1960s and ’70s, when women were increasingly entering the workplace and subject to a dress code that required skirts or dresses but forbade bare legs. “Normally when you wear them, it’s a tense situation for a woman…work, a conference, a party,” Nengudi said. “It’s rare that it’s a casual thing. So they’re part of a tension that women go through when they have to suit up.” Perhaps there remains an anachronistic or ironic attachment to pantyhose among different sets of consumers, but they’ve mostly gone by the wayside for a reason: they rip or run easily, they trap heat and moisture, they aren’t biodegradable, and they’re expensive. They also enable a woman to alter the color of her skin at will, a kind of makeup for the entire lower half, pitting natural against synthetic in the most obvious terms, a taboo in both feminism and black nationalism, each of which privileged naturalism. In sum, they were a pretty successful means of inflicting private humiliation on women during their moments of public visibility⎯patriarchy at its most passive-aggressive. All this is to say that a discarded pair of pantyhose⎯and Nengudi worked with only discarded pairs⎯is not a neutral object, but a way for Nengudi to broach some of the gender issues that make pantyhose such a fraught symbol to begin with.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, March 1978. Photograph of Franklin Parker.

For all of the progressive thinking that emerged from African American thinkers, speakers, and activists in the 1960s and ’70s, Nengudi characterized the era as still plagued by issues regarding patriarchy and respect between black men and women. The push for civil rights frequently omitted gender equality from its agenda, and feminist artists, theorists, and agitators were mostly white, leaving black women in a particular position of invisibility. The historian Molefi Kete Asante writes that African American myth and ritual primarily deals with social relationships⎯between family members as well as to outsiders. This is clearly the case in Ceremony for Freeway Fets, which Nengudi envisioned as a unity ritual to fuse forces that in her eyes were engaged in undermining one other. Asante emphasizes the untenable position of isolation for an oppressed class or a tribe in crisis; true freedom, he asserts, needs to be won communally.

In other words, a release from the ghosts of past and present oppression would necessitate a flight⎯a war⎯and wars are won with unity and communication. The Panthers were one take on this: community togetherness and support systems, education platforms, and the threat of violence if necessary. Another is Sun Ra, whose “eccentricity” seems a little less exotic when contextualized in its moment. Sun Ra’s version of the fight was a kind of cosmic black nationalism⎯black power sought in the interstellar realm. Here are the collectively chanted lyrics to his “Outer Spaceways, Inc.”:

If you find earth boring

Just the same old, same thing

C’mon sign up

With Outer Spaceways

Incorporated8

The fight as envisioned by Sun Ra is a cultural reinterpretation of present and future that delves into a deep African past, and it’s no coincidence that the same 1971 album, The Solar Myth Approach, includes a song called “Pyramids.”9This is the opposite of integration advocacy; it’s cosmic flight.

That same year, Sun Ra taught a class at Berkeley for one legendary semester. Though it was a popular audit with community members, “The Black Man in the Cosmos” had most students promptly dropping the class within a few weeks. The reading list was extensive and demanding, stuff like The Egyptian Book of the Dead, Theodore P. Ford’s God Wills the Negro, David Livingston’s Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, the Leroi Jones–edited anthology of African American writing Black Fire, and sundry other texts touching on ruins, etymology, and African history. Call it the portrait of a philosophy. At that point in his arc, Sun Ra was concerned with extracting man’s potential as an astral being, showing how harmonizing⎯the matching of vibrations⎯could be as much a life concept as a musical one. In Ra’s cosmos, vibrations might connect individuals, cultures, or space-time continuums. The Panthers’ fight happened in the junk strewn streets; Ra’s was to be among stars and meteors, and in his 1974 film, Space Is the Place, he makes his most forceful argument for black Americans to follow him there.10

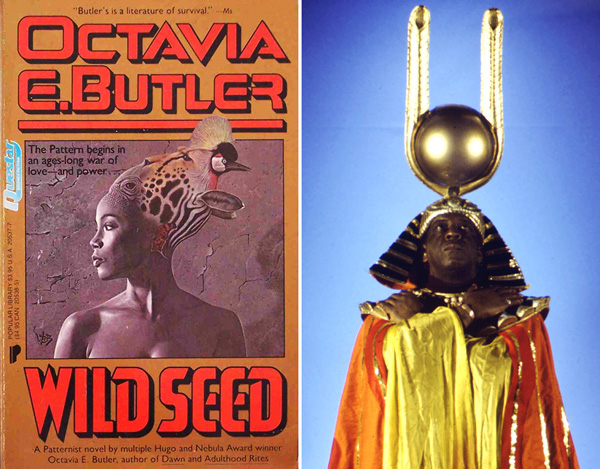

Left: Cover of Octavia E. Butler, Wild Seed, 1980. Right: Sun Ra in Space is the Place, 1974.

Many were on board (George Clinton, Albert Ayler, Octavia Butler), but black American visual art never got quite as cosmic. Perhaps because of the visible and influential examples of Purifoy, Outterbridge, Betye Saar, and several other local assemblage artists affected by Watts, Nengudi remained primarily tied to the object in the 1970s, even in her performances. But ritual and its potential to tap the past as a source of spiritual renewal was constant in her work and that of the other Studio Z artists during the period. Whether it’s Nengudi gravitating toward that dusty, almost rural environment that “had the sense of Africa” for Freeway Fets or Conwill describing his 1976 show at The Gallery as “serv[ing] as a bridge from…ancestral memory to the technology of today,” (the pamphlet shows a Conwill installation of a drum, a drinking vessel, and other talismanic objects arranged on a rug and photographed in a grassy field), the connotations were the merger of ritualism with the street.

“The street finds its own use for things,” wrote cyberpunk sci-fi novelist William Gibson. Nengudi and her collaborators found their own uses for the street, which led them into obscure stretches of Los Angeles’s surreal terrain: decay, desert, and unkempt tropicalia, all bounded by the shimmering, futuristic symbols of abundance that are never too distant. Nengudi’s decision to stage not only a public installation, but also a ritualistic ceremony underneath a freeway in a spot frequented by local transients speaks to the drive and possibility to create a new future out of what is given, even if that is a scene of urban devastation, a faraway planet, or in this case, a blank spot.