So Much for Philanthropy: the Marciano and “All the Usual Suspects” — A Los Angeles Perspective

by Dr. Nizan Shaked

Exterior of Marciano Art Foundation, housed in a former Masonic Temple on Wilshire Blvd in Los Angeles, 2019. Photo by Yoshihiro Makino.

Editor’s note: “So Much for Philanthropy” is (1) of (2) features written by Dr. Nizan Shaked for East of Borneo’s Museums in Crisis collection. Read Nizan’s corresponding article, “Beyond the Bailout: Toward a Post-Pandemic Art World,” here.

***

MAFU member holds up protest sign outside Marciano Art Foundation, 2019. Photo courtesy of Marciano Art Foundation Union (MAFU).

In November of 2019, days after the Marciano Foundation Visitor Services Associates (VSAs) declared intent to unionize, the shuttering of the Marciano Art Foundation in Los Angeles left about 70 art workers out of a job with little advance notice.1It blew the cover off a system that relies on philanthropists to self-regulate, presupposing their benevolence.2But philanthropy assumes inequality. Translated from its Greek and late Latin origins as “love of mankind,” with love referencing care, it is distinguished from charity by its aim to remedy problems from the root cause rather than to simply provide immediate relief. Yet, the worldview that shapes its methods of analysis, and hence the ways in which it conceptualizes change, ensures that the system stays intact: keeping the givers giving and the receivers in perpetual gratitude, if not servitude.3Studies evidence that the exponential systematization and growth of philanthropy has gone hand in hand with an escalating wealth gap, now at a rate last seen in the early 20th century.4The United States is distinguished by the disproportionately high tax incentives it lends philanthropists, resulting in a system that scholars have shown to yield mediocre results at best, and literally exacerbate inequality, at worst.5

When it comes to the arts, the network of nonprofit institutions and public-private partnerships collectively contributes more to inequality than to economic or demographic diversity.6Top-down attempts at diversifying exhibitions, collections, or boards are better than nothing, but are akin to band-aids where surgery is needed. Foregrounding small victories as rule rather than exception, the liberal tendencies of the artworld — believing that capitalist democracy can function properly if only reformed — allows us to overlook how art serves the ruling class.

Marciano Art Foundation VSAs protesting layoffs outside Scottish Rite Masonic Temple, 2019. Photo courtesy of MAFU.

The Marciano artworker action followed a renewed wave of unionization and museum protest.7I say renewed because the collective Ultra-red, whose involvement in the tenants’ rights movement is one of the most relevant practices of art and activism today, have highlighted labor abuses and union-busting by the Marcianos over two decades ago.8

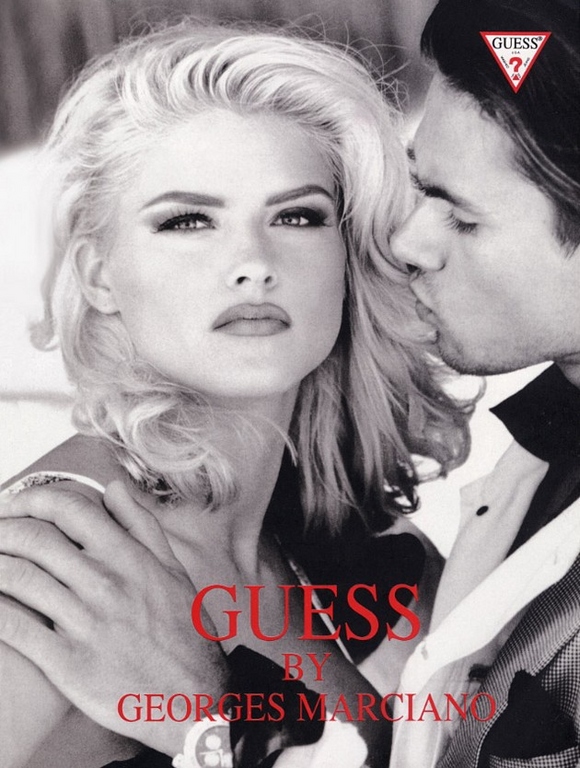

In 1997, a major feature on the Los Angeles political landscape was the anti-sweatshop campaign against local apparel manufacturer Guess? Inc. Community and artists’ initiatives such as the Common Threads collective joined forces with UNITE! (Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees, AFL-CIO) in bringing public notice to the widespread use of sweatshops locally and around the world by companies like Guess. The campaign drew so much attention, particularly with large scale student involvement thanks in part to the public support of rockers Rage Against the Machine, that Guess felt compelled to launch libel suits against artists and community members. In one egregious case, members of Common Threads were slapped with a libel suit for an anti-sweatshop poetry reading they sponsored at an L.A. bookstore.9

But the response of the liberal art world fails on two accounts. First, media shock reveals the assumption that the Marcianos would not treat their art workers as they have their garment laborers. Second, the liberal view assumes that the Marcianos’ wealth belongs to them, and not to the garment workers who actually created it. The Marxist understanding that wealth is socially, not individually, created — that it is the labor of workers that add value to the economy, while everyone else, necessary as they are, function to distribute it — is key to the structural change essential for political, economic, and ecological survival. When socially-created wealth is equitably distributed there will be no need for philanthropy as we know it. The upside is that the faith that capitalist wealth will trickle and fund the art world is now rapidly dissipating. Ill-begotten money, and the audacious behavior of philanthropists have revealed “generosity” to be a fetishistic mythology.

The “Summary of Direct Charitable Activity” in the Marciano IRS I-990 PF tax-returns simply states: “Operation of Art Museum.” Art world insiders have always been skeptical of the Foundation’s claims to be a museum. As Jori Finkel self-critically lamented, it turned out that it was “the shell of a museum”:

The Marciano Art Foundation, created by Guess founders Maurice and Paul Marciano to showcase their contemporary art holdings, was from the start a private collection masquerading as a museum. It was the shell of a museum, the illusion of a museum or — maybe most deceptively for those of us who judge an institution by its facade — architecture worthy of a museum.10

Finkel distinguishes the Marciano from what she sees as the publicly-accountable Broad. But in admitting that journalists, herself included, have been: “mistaking semi-private art collections for public art museums,” Finkel misses how the Broad and Marciano are much more similar than they are different, as well as the opportunity to ask why are institutions receiving massive public subsidy by way of tax exemption for their operations and a reduction of income tax for their donors, opaque to public scrutiny. Finkel also misses the point that “shells of museums” are now actually sanctioned by the American Alliance for Museums, which has: “revised its official definition of a museum “to insist only on the use of objects, not on their ownership’.”11

Why are we accepting at face value that these institutions merit public subsidy? Using the work of political scientists, geographers, and other scholars, I argue that the current tax code in the US gives philanthropists a combination of exaggerated tax subsidies and concrete control over policy and civil society, the combination of which results in an undemocratic, if not plutocratic, or oligarchical political reality. Liberalism fails its own promise that the excesses of the free market will be fairly redistributed. When it comes to art, advantages of the wealthy are exacerbated since the status of art as an asset, or as the euphemism goes: “passion asset,” distinguishes collecting institutions (or shell institutions serving collectors) from all other types of nonprofits. Donors to hospitals, universities, think tanks, or nonprofits providing social services do not share financial interests in the same assets owned by the institution they serve. But Broad and Marciano privately own works whose price can appreciate at public expense. The same goes for board members in institutions varyingly more public, as the Museum of Contemporary Art, Hammer Museum (UCLA), or the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). If trustees are pushing to collect or exhibit artists’ works that they themselves own, they are serving themselves, breaching the ethical justification of the liberal nonprofit institution.

1992 Guess? ad featuring Marciano’s then muse Anna Nicole Smith, whose Guess campaign helped define the global brand. Photo by Daniela Federici.

The most important point is that philanthropy merely gives back the surplus it has siphoned from labor and also from externalities paid for by society’s taxes. The ability to privately appropriate socially created wealth is historically specific to the economic forms of capitalism. That great wealth is an outcome of the system, not only of talent or business acumen, is evidenced by the fact that the fortunes of the Robber Barons pale in comparison to the ultra-rich today. The difference is not just that the newer group is better at manipulating the system, but that technologies of communication, transport, and automation, together with the politics of globalization and the economics of neoliberalism allow for the amassing of unimaginable wealth, where disposable income is poured into political manipulation, ideological controls, and yes: art.

This system is set up to mask how the economy actually works. But for a scholar like Ruth Gilmore Wilson the fact that wages are theft is clear:

While we bear in mind that foundations are repositories of twice-stolen wealth — (a) profit sheltered from (b) taxes — that can be retrieved by those who stole it at the opera or the museum, at Harvard or a fine medical facility, it is also true that major foundations have put some resources into different kinds of community projects, and some program officers have brought to their portfolios profound critiques of the status quo and a sense of their own dollar-driven, though board-limited, creative potential.12

While it’s true that a plethora of small-scale individual giving supports experimentation and pluralism, and that nonprofit workers may earnestly be doing good work, the constraints and fragmentation enacted by the system prevent actors from connecting the dots, seeing the big picture, thus thwarting the formation of large movements. Even if one does not agree with a leftist understanding that the economy functions as a giant pool, from which some individuals are allowed to take more, the political conclusion still holds. The capitalist logic of competition that permeates the third sector ensures that arts leaders too never come together in revolt against the funders or the system. The structure dictates that they comply with capitalism.

Liberalism Fails its Own Promise

Generally, there are two types of museums: private operating foundations (I refer to them as publicly-subsidized), and public charities “that receive substantial support from a governmental unit or from the general public” (henceforth publicly-supported).13The latter are subject to greater scrutiny, but in effect are also only regulated by tax law and state attorneys, leaving them open to various types of manipulations.

Most recently, Christopher Knight pointed out the questionable entanglement of LACMA director, Michael Govan, who organized corresponding exhibitions of Thomas Joshua Cooper: one (co-curated with Rebecca Morse) at the publicly-supported LACMA, and one at the commercial gallery Hauser & Wirth; compounded by an additional gnarl of board service and sponsorship deal connections:

A commercial exhibition conceived and assembled by a nonprofit museum director who is the head of a county department subsidized by taxpayers … creates an ethical swamp of considerable depth. Neither LACMA’s board of trustees nor the L.A. County Board of Supervisors should stand for it.14

Govan and his staff are paid for, at least in part, by the public purse. Does the public institution get compensated for the time and reputation they give private entities when publicly supported staff moonlight for galleries and art fairs?

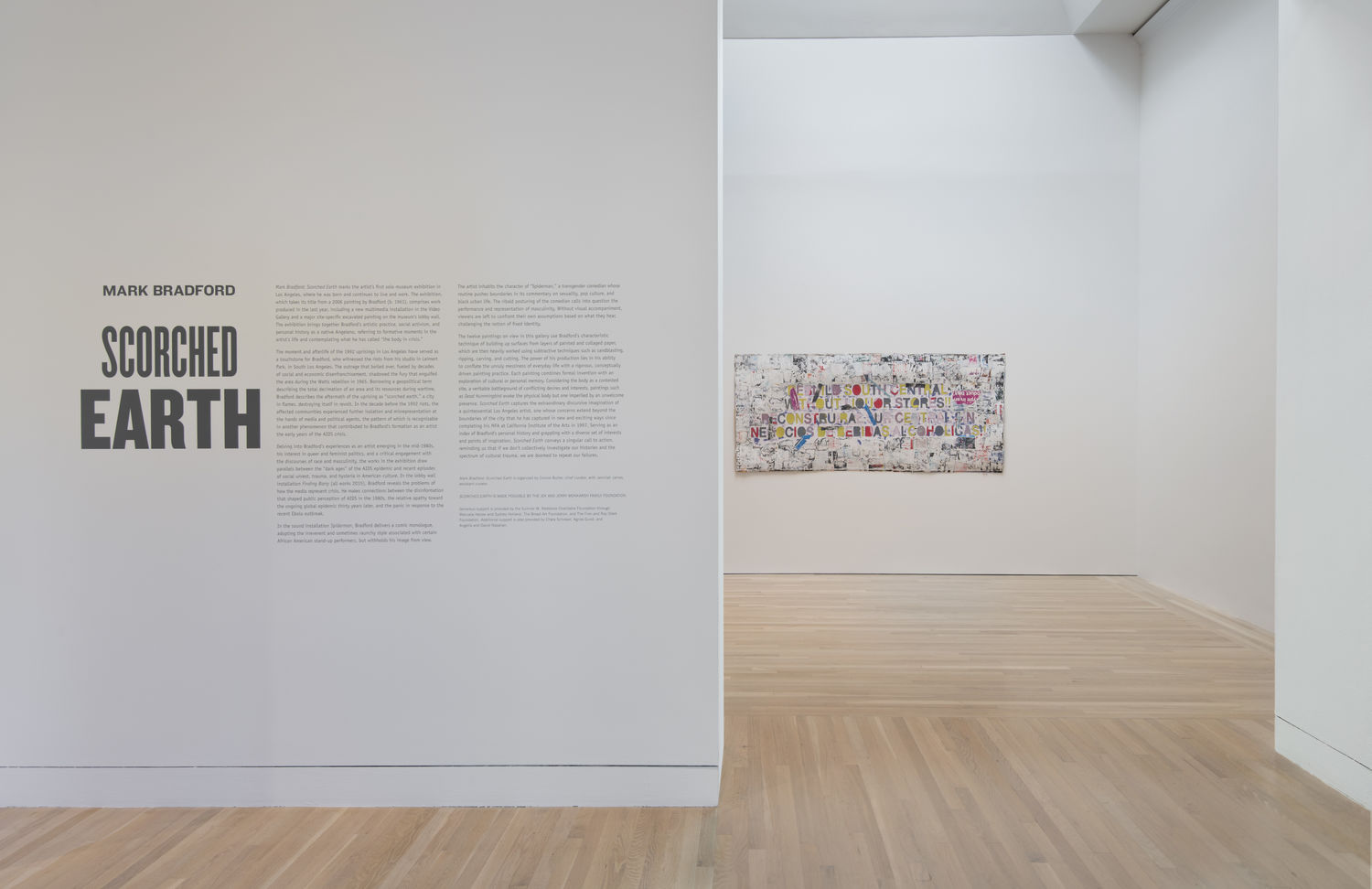

Although Hauser & Wirth offers services in an attempt to look like a public institution, they are not, and are therefore not subject to the same ethical and legal pressures. Publicly supported or subsidized museums should resist the branding impulse of galleries and collectors. Although it avoided Knight’s public scrutiny, I am sure he is aware that the Mark Bradford exhibition at the Hammer, Scorched Earth (2015), had its fair share of ethical conflicts. Separate from the lobby commission, the entire painting section was nothing but a gallery show of a new body of work (evidenced in the “courtesy of Hauser & Wirth” printed on the tombstone labels). If, as a board member told me under conditions of anonymity, the museum knowingly compromised itself so it could obtain a financially out of reach Bradford, we have to ask ourselves not only how far are museum directors willing to go, but also why does every museum need to have a Bradford? This is not about Mark or his work; I like them both and I trust that Mark is secure enough to recognize that I am speaking here of a principle. There are so many artists from under-represented backgrounds that are not brand names, whose work is equally worthy of institutional collection.

Installation view of Mark Bradford: Scorched Earth, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo courtesy of Hammer Museum.

Installation view of Mark Bradford: Scorched Earth, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo courtesy of Hammer Museum.

We witness publicly-supported institutions serving the needs of their wealthy sponsors, not only as a way to glorify donor reputation, but directly — monetarily. Donor pressure on institutions to collect and exhibit the art that they themselves own has long been a problem in the field,15where cash-starved institutions increasingly place their professional staff at inevitable coercive conditions, and where the agency of art stars serving on boards to provide a critical balance is about as potent as the attempt to combat climate change by recycling plastic.

The understanding that what is private or public about money, surplus, revenue, and the tax system are all social constructs and not a natural law, has spread from the fringe to mainstream electoral politics. In other words, there is nothing radical here. Still, in the world of art, dependency on philanthropy leaves us collaborating with what might, from a retrospective future, make present behavior seem like scandalous pandering to the wealthy.

Protesting the sudden layoffs, workers of the Marciano foundations marched to LAXart, a contemporary arts nonprofit, to demand that its board member Olivia Marciano, former artistic director at the Foundation and daughter of Maurice Marciano, speak up in defense of her workers or be removed from the LAXart board. LAXart director Hamza Walker greeted the protestors with respect:

“I can’t say I’m not sympathetic,” he said. “I run a nonprofit art space, just trying to keep it afloat and keep a hospitable back of the house.”

Afterward, Walker told the Times he sympathizes with the workers but doesn’t see Olivia Marciano’s involvement with LAXart as a conflict.16

But it is a conflict. Marciano is part of an organization accused of behaving unethically toward artworkers, if she doesn’t speak up in their defense she is guilty by association. LAXart is artwashing Marciano’s reputation, in the course of which it is damaging its own. In a system of dependency, everyone’s intellectual integrity is compromised. Walker is a brilliant and widely respected curator and art leader. This criticism is not of him personally, but the system that shapes his response. The same goes for using Olivia Marciano as an example of a larger problem. Nevertheless, she is a model of prevalent undemocratic conditions of unequal opportunity. Marciano is ostensibly as qualified to sit on an arts institution board as she is to be the artistic director of another.17If we openly compare her CV with that of her fired VSAs we will find that many of them far outdo her in education and experience. Her service on the LAXart board is connected to the wealth she inherits, itself connected to the exploitation of labor, echoed in the fact that Marciano SVAs were only granted part-time employment and asked to commit in advance with no such courtesy extended to them. To shrug this off, or attribute it to an abstract “contradiction,” is to sustain the status quo. Anyone claiming cutting edge, social consciousness, or commitment to critical discourse should do the work of describing how things are connected.

Olivia Marciano can be hired by her father and uncle in their private business for any role their hearts desire. But the Marciano Foundation is publicly-subsidized. It shouldn’t be too hard to imagine regulations requiring publicly-subsidized institutions to hold open processes, comparing education, potential, and experience in order to hire the most promising candidate for the job. For the curatorial and other programs there need to be diversity requirements that intersect race and ethnicity with class and demand for methodological diversity in collections and display. It is no surprise that in the current deregulated moment private collections exhibit a commitment to real-estate-scaled painting: “paintings the size of a city block” — as Ultra-red co-founder Dont Rhine once pointed out; or that diversity appears mostly when it comes with the stamp of market approval. To eliminate white supremacy, in its historical and contemporary connections to capitalism, we need real diversification, from the bottom up, not corporate lobby tokenism.

So, who owns the art? Anyone following the art market and reading the I-990s of private namesake institutions will be able to speculate that collections circulating in and out of publicly-accessible buildings are worth much more than the assets listed.18If the Marciano Foundation has access to 1,500 works, and the Broad says it is “home to 2,000 works,” it becomes evident that these institutions are also exhibiting the personal artwork of their donors and thus raising the value of privately held works.19It is easy to argue that this alone should suffice as public subsidy and that private museums should receive no additional monetary support; they are already receiving public subsidy because the public that views their work is a key driver of its price appreciation. We shouldn’t pay an additional dime, or tax dime, to see any work that has not been placed in the public trust. The need for tax incentives is not fact but custom. The idea that a person owns their pre-tax money is a historical construct, not a fact.20Massive philanthropic investment took place in the US prior to the implementation of various tax subsidies. Early philanthropy gave for reputation and a sense of obligation. But actual philanthropy can only be extant when the giver has not made their fortune through a crisis prone system based on exploitation. Nevertheless, since the 1940s, law and policies have been changing to accommodate wealth accumulation, rather than curbing it toward a more equitable and re-distributive society21

Tax Law: or How the Rich Receive Public Subsidy

In the 2018 art market documentary The Price of Everything, collector Stefan Edlis explains his method of upgrading his collection “of all the usual suspects” by trying not to buy, but rather officially exchange artworks: “Some people think that uncle Sam is not getting his cut, which is probably true, but that is also true in real estate, and as long as the laws are there to do it, it’s a good way to build a collection.”22

The law favors the wealthy. The wealthy exploit it because they can. We have a problem with the law.

Political economist Rob Reich charts a history of mistrust and curbing of philanthropy.23Demonstrating how philanthropy can be the cause of inequality, he argues convincingly that today “donors are not exercising a liberty to give their money away; they are subsidized to exercise a liberty they already possess.”24 For perspective: “in the United States, for example, subsidies for charitable contribution cost citizens at least $50 billion in foregone federal tax revenue in 2016.”25That is $50 billion of unregulated money changing hands through obscure arrangements.

Reich shows the two major ways in which tax law favors the rich over the middle class and the poor. First, 70% of taxpayers that take the standard deduction are arbitrarily excluded from the charitable contribution deduction. Your donated $100 and an itemizer’s donated $100 are treated differently by the law. That 90% percent of American households make a charitable contribution every year is proof enough that no incentive is necessary for philanthropy. Moreover, “low-income individuals give away more money as a percentage of their income than does everyone else except the very wealthiest.”26In terms of percentage, poor people are more generous than the rich, both of which give more than the middle-class. The second advantage, the “upside-down effect,” where the state subsidy becomes larger as one climbs up the tax bracket, is quite infuriating.27Simply put, the wealthier someone is the bigger the subsidy for their donation. In 2017 a person in the 10% tax bracket paid $100 of their $100 donation, while it cost a person in the top income bracket only $60.4 to donate the same $100. These laws could easily be remedied by allowing non-itemizers to deduct contributions, or by offering identical and capped tax credit for all donors.28Yet they are not.

As if that was not enough, until the recent overhaul of the tax code collectors could also exploit the like-kind exchange law, “a tax-deferred transaction that allows for the disposal of an asset and the acquisition of another similar asset without generating a capital gains tax liability from the sale of the first asset,” for selling and buying art. In California there is also a “Works of Art Exemption” that “provides a property tax exemption for certain works of art that are made available for display in an art gallery or museum.” Imagine the amount of public money lost when property tax from a Gerhard Richter remains in the pocket of the collector who parked it in a nonprofit in Oregon (not to speak of the growing trend of art storage in tax freeports). The system is exploited thrice: first, when we leave the wealthy untaxed; second, when a public institution is used to help wealthy donors pay less taxes; and third, when a public institution is used to prop the market of a “usual suspect.” Is it so hard to imagine that the audience of the latter nonprofit would benefit just as much, or probably more, from seeing an artist for which the sales tax would be much lower? It might even be the work of an underrepresented artist who does not output blue-chip paintings faster than I can type words.

There is another interesting comparison between art and real estate. Reich points out that with nonprofit foundations of public school PTAs in well-off districts, publicly subsidized deductible contributions by parents not only go to educating their own children, but given that real estate prices are tied to school performance, it raises their home equity. The tax system is supporting the wealthy getting wealthier. Given the demographic distribution, where wealthier neighborhoods are statistically more white, we must underscore that, on a social scale, these nonprofits are systematically subsidizing a system that sustains white supremacy.

United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) protesting Broad’s charter school plan outside the Broad Museum, Los Angeles, 2015. Photo courtesy of UTLA.

Furthermore, donors that have their own art institutions see a plethora of additional advantages.

We could ask: who pays for shipping and insurance when works are moved between storage facilities and the various residencies of donors? Who pays for staff time when fire or flood danger threatens second and third homes or offices and mega-expensive works are shuttled around? What kind of expenses are written off on publicly subsidized balance sheets? Such information, and much more, is hidden from public view with no regulation in sight.

That wealthy individuals benefit financially from the tax exemptions conceptualized to encourage philanthropy is in fact quite legal, as Alex Kirk writes:

Generally, the presence of a substantial private benefit will disqualify an organization’s tax-exempt status. However, even substantial private benefits may be tolerated if they are considered qualitatively and quantitatively incidental in comparison with the organization’s charitable goals. Qualitatively incidental private benefits are “a mere byproduct of a public benefit,” whereas, quantitatively private benefits should be insubstantial in amount. A qualitatively incidental “private benefit must not be substantial after considering the overall public benefit conferred by the activity.” According to the IRS, some private benefit is qualitatively permissible if “the benefits from the organization’s activities flow principally to the general public . . . [and] [a]ny private benefits derived . . . do not lessen the public benefits flowing from the organization’s operations.” Furthermore, the IRS ruled that “it would be impossible for the organization to accomplish its purposes without providing” some private benefit.29

The rub is that it is up to the donor to determine what constitutes “public benefit,” casting all sorts of self-interested decisions as such. “A private benefit is quantitatively incidental if it is ‘a necessary concomitant of the activity which benefits the public at large, i.e., the activity can be accomplished only by benefiting certain private individuals’.” 30 With the market for contemporary art skyrocketing, and the tax code incentivizing mega-collectors to open private operating foundations rather than donating works to established publicly-supported museums, we have a proliferation of institutions sporting “all the usual suspects.” What all these suspect institutions do collectively is raise the price of their private assets, all the while lowering their taxes. The concomitant bubble effect is damaging museums and artists.

The “Medici” Metaphor

Many, including himself, lament that Eli Broad stands out as a single mega-donor in a city weaker in philanthropy than its East-coast rivals. However, the real problem is not that there are not enough donors, but rather there is not enough taxation and equitable distribution of wealth to collective coffers. Unregulated, de-skilled, and shortsighted, the billions poured into philanthropy are erratic and fragmented as its primitive, pre-enlightenment, variant. The notion that layman control is somehow better (“freer”) than elected officials, specialists, and experts administering a larger picture with oversight, transparency, a horizon set on posterity, and rigorous metrics (beyond popularity ratings) is a dangerous American myth.31Significantly, that supporting charter schools lost Antonio Villaraigosa the California Democratic primaries is a stark vote against the tax-exempt war of Broad, Alice Walton, Doris Fisher, and of course Bill Gates against public education.32Moreover, when philanthrocapitalists seek instant “returns” on “investment” they create a debilitating culture of sugarcoated proposals and reporting.

And then there is always the possibility that they can just give money directly to themselves. Instead of donating his collection to LACMA, Eli Broad decided to maintain control.33

You’ve got so much of yourself invested in your collection, … you want to share it with the public, and it’s difficult to get museums to commit to what you want. They’re going to show the collection a fair percentage of the time, as opposed to what you want, which is for it to be shown 80 to 90 percent of the time.34

As impressive as it is, the Broad is a private collection and not a museum. The architecture also sends this message. Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler, the building’s heralded vault & veil architectural concept becomes an overstated metaphor of a private vault — veiled as a public service. Of the 120,000 square foot building, only 50,000 is exhibition space.35With some gallery space and a shop in the lobby, it is a box holding the collection and offices, with a few medium-sized galleries on top, reached through a sensuous escalator well. The exoskeleton covering the interior creates an affective vast space with no columns or load-bearing walls. As you descend the exit staircase, you can peer into the storage: the trove beyond scrutiny.

That when it comes to art Eli Broad is a layman, is everywhere on display. From the banal quotation about how artists reveal the world that crowns the main label, to curatorial crimes such as reflecting the work of Mark Bradford in Jeff Koon’s narcissistic tulips, or blocking the view of a Lari Pittman painting by parking a Koon’s train in front of it, the institution is, in the words of one undergraduate student: “the museum of Selfie.” Curiously, a VSA with whom my student spoke did not explain the key referent of Koons’ inflatable vanity: the 17th century Dutch Tulipmania, the world’s first economic bubble. So much for service to education.36

It’s not all bad though. Broad bought Jean Michel Basquiat good and early and it’s wonderful to see so many of them together. He also displays truly significant Ellen Gallaghers. But why hasn’t anyone told him, as many artists have commented, that if the practices do not relate, it’s kind of, ahem … not the brightest curatorial idea to hang all the African American artists in the same room?

There is much more to say about the only man in history who started two Fortune 500 companies and who, nevertheless, almost got an annual $1 land lease, if not for the sobriety of Los Angeles County Supervisor Mike Antonovich.37Broad did however get a sweet deal on the parking garage. And here’s another wow factor write-off: building the chef restaurant Otium is declared on the 2015 Broad Foundation I-990, as uncovered by the artist Shevaun Wright. I cite in full the “Summary of Program Relates Investments,” because this deduction justification is truly artful.

To support the continuing development of Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles as the city’s cultural core by building and operating a restaurant on the public plaza adjacent to the Broad museum and centrally located to public arts and cultural destinations the charitable goals and activities of the restaurant include 1) supporting the Broad museum by providing food services to its staff and visitors, and by enhancing Broad’s public programs (for example, by conducting food education talks for kids as part of the Broad’s “family day” and providing refreshments for Broad’s “summer happenings”), 2) attracting a new, economically and culturally diverse population to Grand Avenue by creating a relevant and welcoming amenity, 3) thereby helping to a build a broader-based audience for the Broad and other cultural institutions on Grand Avenue, 4) providing job training to low-income and at-risk individuals, and as anticipated, 5) providing charitable programs to local schools.

Is the “economically diverse” population expected to pay a chef restaurant bill? Can the Broad VSA staff afford to eat there? Is the restaurant really providing all the charitable activities listed? Is the private benefit here “quantitatively incidental”? Are we even able to obtain the information necessary to answer these questions?

Foundations, as private institutions that nevertheless must provide more public service than they gain their donors, lack a clear definition of what is to be considered public or private, and the appropriate requirements for transparency. It would be interesting to test in court whether, given the public subsidy of private operating foundations, they should be subject to freedom of information act requests. This would force the necessary distinction between the private or public aspects of these hybrid entities. But who would pick up such a task? Fittingly, artists.

Shevaun Wright: Class Action

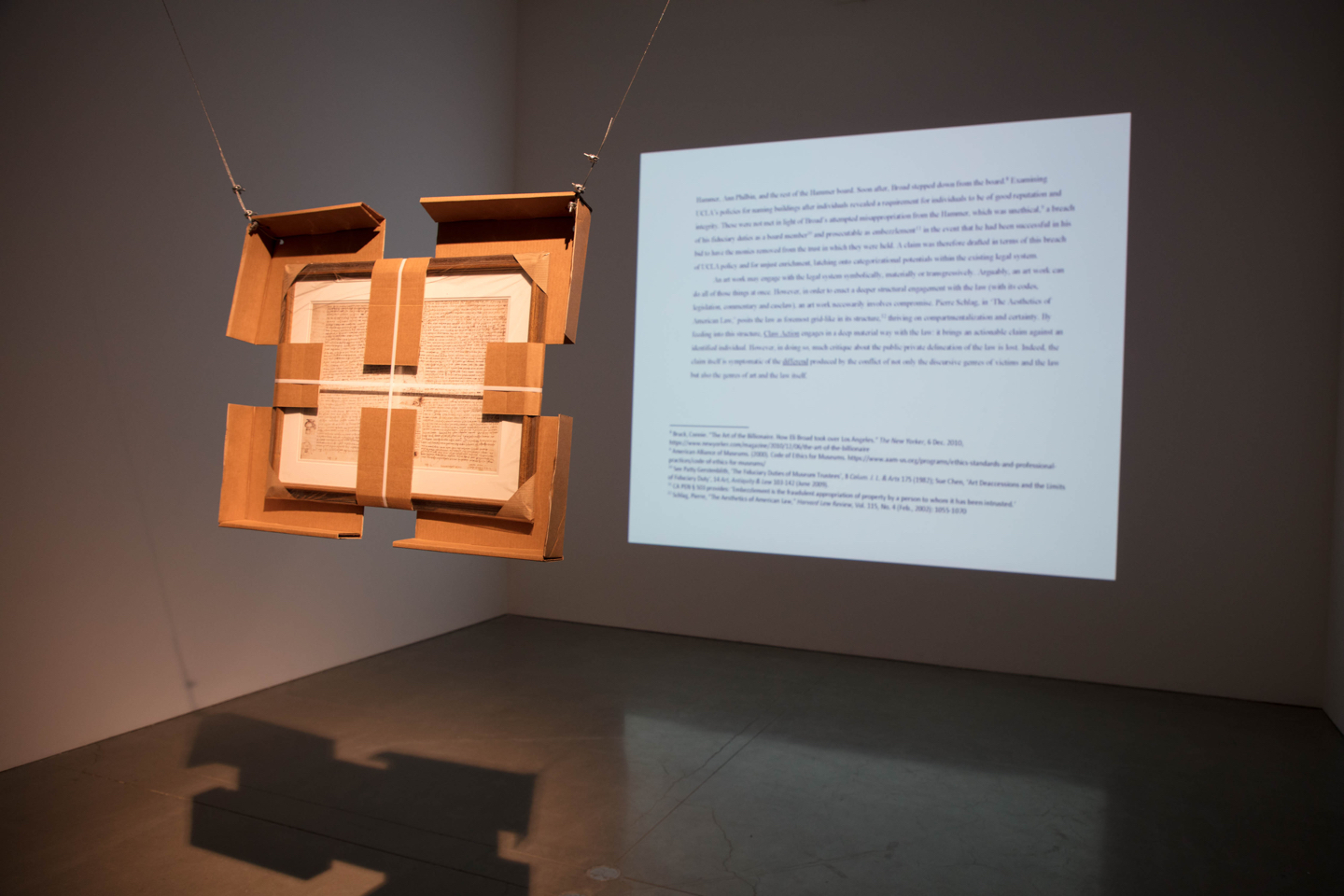

Shevaun Wright, “Class Action,” 2019, New Wight Gallery, UCLA thesis show, installation view, dimensions variable. Photo by Sam Richardson.

Shevaun Wright, “Class Action,” 2019, New Wight Gallery, UCLA thesis show, installation view, dimensions variable. Photo by Sam Richardson.

Shevaun Wright has drafted and served a class action on Eli Broad for unjust enrichment at the expense of her and her fellow students at the UCLA School of Art, where Class Action commenced in 2019 as her MFA thesis exhibition. Wright has also delivered two letters to the university’s president, asking for Attorney General oversight in removing Eli and Edythe Broad’s name from the School of Art. At Broad’s council and shepherding, the Hammer’s deaccessioning by auction of the Leonardo da Vinci Codex in 1994 fetched more than anticipated. Subsequently, Broad tried to appropriate and redirect $10 million dollars toward a donation to the UCLA School of Art in his name. Deterred by the newly appointed Hammer director, Ann Philbin, and the chairman, Broad quietly left the board.38Had he been successful, as Wright argues in her letters, Broad would have breached his fiduciary duties and committed embezzlement. The renaming of the school thus violates UCLA policy that specifies donor reputation and integrity. In response Wright served Broad with a demand for $1,000,000 in restitution payment, representing approximately 0.0068% of the total capital gains tax rate that would have been paid on the Broad Foundation’s art collection had it not been tax exempt. Wright demands the sum be administered to one or more domestic violence service agencies she lists.The work’s connection to domestic violence was driven by the relationship between private spaces and domestic violence, and the aggression the artist felt towards the inherent gender bias of the law. These are the same spaces where Broad either made his wealth or claimed glory for his economic prowess. Of course, Mr. Broad is not responsible for crimes committed against women in the spaces he built, but his ability to enrich himself is anchored in violence and discrimination inseparable from an exploitative class system of crisis-capitalism.

The system utilized by Broad to amass his riches is now used by one smart agent (Wright) who identified a key flaw, activating it as a blueprint for fixing the future by fixing the law. Wright shows how litigation does, or does not, fit within private or public rubrics subject to the rigidity of what she describes as the grid-like structure of the law (citing Pierre Schlag). Domestic violence and rape, for example, might be litigated as personal and private even though they are social, political, and also necessarily spatial. The new field of emotional geography has used feminist criticism to address such complexities. In art Wright is a pioneer, going deeper than revelatory institutional critique with actual material intervention. Although the claim addresses Broad personally, the artwork acknowledges the limits of the law in pursuing individuals on narrow bases. But Broad is a model, such that if Class Action is successful, it will set precedent.

Shevaun Wright, “Class Action,” 2019, New Wight Gallery. Wright’s installation included a map that led viewers to this Broad Art Center placard displayed at UCLA’s New Wight Gallery. Photo by Sam Richardson.

Also indirect yet nevertheless connected, the racist geographies of white flight and suburbanization benefitted Mr. Broad financially. Dancer and scholar, Olive Mckeon, is right to insist that we cannot separate the philanthropists from the consequence of their wealth accumulation. In relation to Gloria Kauffman, the wife of Broad’s first business partner, Mckeon shows how arts “funding is bound up in the history of suburbanization, white flight, and urban redevelopment in the Southern Californian context:”

Whiteness, as opposed to a smattering of distinct European ethnicities, became the product of suburbanization and its logic of racial exclusion. … The values embedded within suburbia — homogeneity, containment, predictability — correspond to the emptying out of distinct ethnic identities that is characteristic of whiteness. The success and scale of Kaufman & Broad’s business depended upon and fueled these larger patterns concerning the racial politics of space in the postwar context.39

Contradicting the free-market values they support theoretically, Broad and Kaufmann used an anti-competitive combination of financing and manufacturing to commodify housing by eliminating the basement, cutting costs, and compensating for losses with production volume, becoming the number one housing mass producers in the US. Housing for profit inhibits the creative thinking and joy we could have if we worked on shelter collectively, rather than competitively. If housing was treated not as a sellable object but a basic human need, the agenda, the spaces, the design, the aesthetics, would be entirely different. Driving through endless Arizonas of KB homes is evidence enough that Broad is an enemy of aesthetics. There is no reason for the public to subsidize his, or the Marciano brothers’ personal taste in art, let alone use it to glorify or artwash their reputation.

_

Special thanks to Eric Falcon for introducing me to Shevaun Wright’s work, and to Kimberli Meyer for the discussion.