Beyond the Bailout: Toward a Post-Pandemic Art World

by Dr. Nizan Shaked

Editor’s note: “Beyond the Bailout” is (1) of (2) features written by Dr. Nizan Shaked for East of Borneo’s Museums in Crisis collection. Read Nizan’s corresponding article, “So Much for Philanthropy: the Marciano and “All the Usual Suspects” — A Los Angeles Perspective,” here.

***

The response to the Covid-19 pandemic by the art establishment in the US did not take long: with much regret, mass firings of workers 1have been announced by major museums. This alarming reaction was countered by a few examples of emergency bailout by more ethical institutions, including an initiative by the Getty,2 intent on upholding the system until the storm passes. But will the storm pass?

We can’t predict the future, but we do know for certain that more disasters are coming our way. Mass farming, global warming, world connectivity — all conditions are ripe for sweeping catastrophes. Are we prepared? Of course not. Yet, as several commentators noted: if we are able to coordinate social distancing in response to the pandemic, surely we could synchronize solutions for the climate crisis. The question is: will we?

Let us think through the arts establishment about our current infrastructure: what is not working, and how can we fix it.

The Getty’s $10 million fund can only be a temporary fix. It also signals the ways in which the arts establishment is fragmented, putting institutions into competition with one another. Competition is generally detrimental to our future. To fight a pandemic, we want scientists and industries cooperating, not competing, and definitely not for the purpose of making profit. We want a healthcare system orchestrated wisely to benefit the public. Fragmented insurance companies and stand-alone networks or facilities have been reaping disaster. For-profit physician staffing firms have landed medically traumatized people with additional financial shock. That these institutions operate as separate entities is by design. It serves profit-making. However, it has become evident that this logic, about which socialists and everyone left of socialism have been complaining for decades, if not centuries, is literally killing us. Its most sinister manifestation is the decree of the 45th American president that states should compete with one another for protective gear and ventilators.

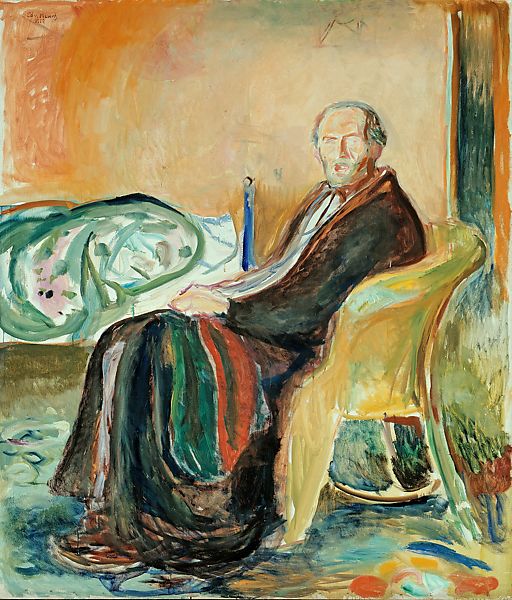

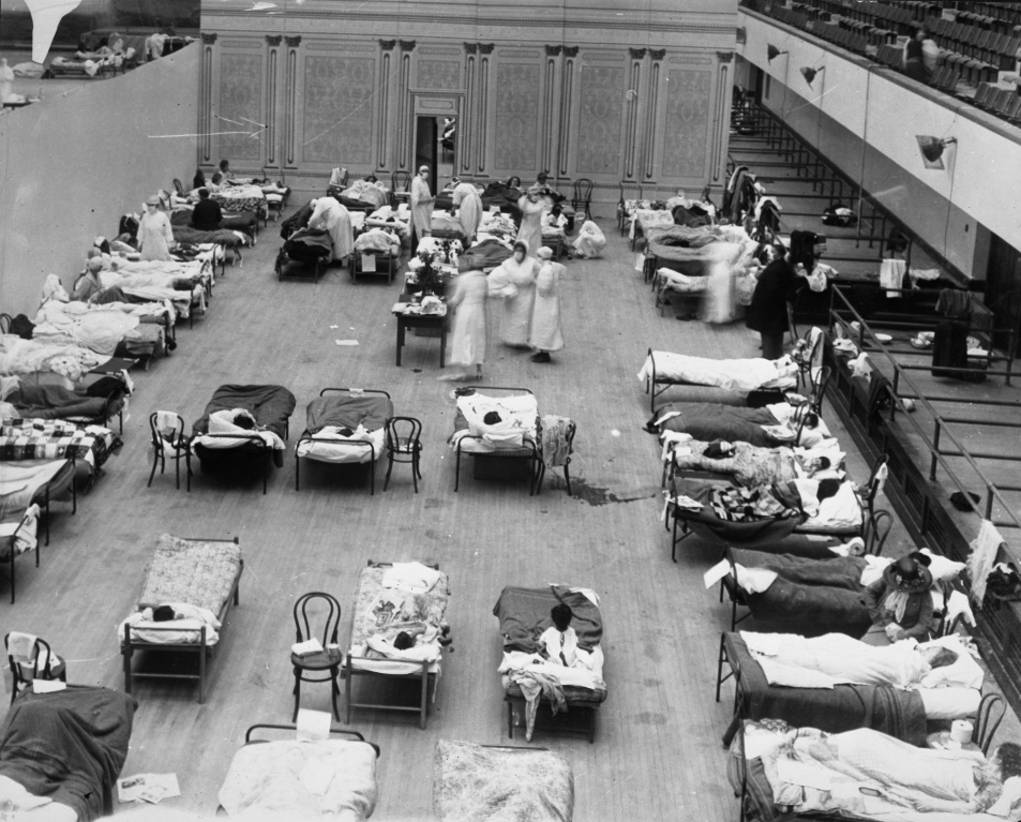

Makeshift Spanish flu hospital at Oakland Municipal Auditorium, 1919. Courtesy of California State Library.

In the art world this all seems more benign. But it isn’t. The art world is a microcosm of the American capitalist nation-state, whose civil society is a collage of nonprofit systems, competing one against the other for the so-called generosity of whomever won the competition in another game. To be good at administering art is to obtain more money than your colleague in another institution.

A museum director once relayed to me an anecdote illustrating why another museum director, widely considered successful, is so effective. At a mixer for museum directors, the story went, all the institutional leaders were networking with one another, while our famed director was “busy putting their hand in every philanthropist’s pocket.” The point here is not that our savvy museum director is at fault; indeed, they are excelling at a game whose rules have been set by larger forces of history. They are doing their job benefitting their institution, its workers, their city, the community, art, and artists. If they stop, their immediate economic infrastructure will collapse, and many people will suffer. Moreover, in the eyes of the status-quo they will have been seen as a failure. But the time has come for us to jump over this conceptual hurdle and look at the larger outcome of such smaller balance of forces.

Up until now, American capitalism, accompanied by its nonprofit welfare structure, was a status quo above which it was very hard to make a leap. Criticism of the nonprofit system and its logic operated and was debated in academic or activist forums weak enough to not pose a threat to the neoliberal machine. But things started to boil over even before the pandemic hit, as evidenced by the shifts to polar extremes on the electoral scene. In this arena dialogue is rendered moot. Humanitarian appeals, such as “Dear Ivanka,” 3fall on deaf ears. Libertarian and right wing constituencies live in realities informed by sets of information so different than ours that it makes a mutual ground for conversation impossible. There can be neither dialogue nor debate — we don’t share axioms. Based on this fact, and analysis of historical precedent, 4I, and many others, conclude that the appeal to a reasonable center is a weak strategy bound to fail. The “return to normalcy” is not an option for all those for whom normality has been a nightmare.

What does this mean for the art world? At the moment we have the bad nonprofits and businesses that, sporting apologies and long faces, have nevertheless fired their workers. 5We have the good guys like the Getty that are doling out money to keep the system floating until its engine can be fixed. We might see limited help from the stimulus bill, but not nearly enough, and definitely nothing concrete, for those full-time or precarious art workers who have lost their jobs. But the moralistic adjudication of who is good or who is bad is not productive right now. The problem is systemic, as critics have been repeating for decades.

Two things have dramatically changed for us at the moment. First, the system is laid bare for us to see. Second, there is no doubt about the fact that we are drowning. Even the brightest prospect of recovery paints a picture that will leave out most of the individuals and institutions (profit or nonprofit) that were barely hanging in there before the pandemic hit. Fragmentation and competition are detrimental. Individuals and institutions that might save themselves will recover into a barren and tragic world — the next disaster looming on the horizon. What then are we seeing now that can help us move forward?

In many ways we have already started. To combat fragmentation, we witness the surge of unionization. There is power in numbers. We move forward aware of past compromises and corruption, determined to learn from previous failures (for example, the repeated historical abandonment of black caucuses and workers by white-led unions). That unionization has not been a bulwark against the recent mass firings teaches us that the scope of the battle is much broader. The answers are outside of arts-activism alone. Alliances of unions can join forces toward a larger front. Most artworkers face housing and/or studio-space challenges: the work of Tenants Together is a model and a gateway to a plethora of resources. Links are formed to multiple tenant unions, nationally and internationally, and larger networks are formed with other organizations and allies. Many homeowners and mortgage holders recognize that specific tenant unions serve everybody’s interests. We don’t have to share identities to form a powerful front of solidarity. Rent strikes, organized or spontaneous (born from individual tenants facing no other choice), are already bubbling, as is the refusal of unprotected workers to serve society for minimum wages or less, while lacking medical and other safety nets. The demand to share all resources is here now. The refusal to pay rent and debt is a strategy on the table. A global rent and debt strike is no longer an impossible proposition. It is potentially a way to total restructuring. Why wouldn’t institutions be bold enough to join? Pay your workers not the landlord. To the MoMA’s firing of their contract educational workers, Seph Rodney proposes another sensical solution: “Literally all MoMA would have to do is pay Glenn Lowry about $1 million dollars less this year (and still leave him with more than a million dollars in compensation) and they could keep these folks paid. Mercenary capitalism at its most self-centered.” Simple: directors should give up their salary for their workers. Are their personal bills too high? If they are on our side, they too could join the debt strikes. After all, directors are highly paid so that they can meet wealthy donors where the latter are. But if we tax the wealth and income of the philanthropists so that they meet us where we all are, it is guaranteed that plenty of talented administrators will in turn be willing to do the work for average pay.

To combat competition, we eliminate the principle of profit. All surplus is pooled and divided by need. Art institutions and artists get their fair share of the total pie. Art is not a luxury. Art is a basic human need. It is a fact of human history that in the worst conditions of confinement, imprisonment, and starvation, people have persisted to make art. It is capitalism that has cast art as a luxury. Art was made before capitalist collectors made it expensive and art will be made after capitalism is gone. Capitalism will be gone because it is a system ill-suited to combat pandemics and environmental disasters. The task of art now is to find its role in the struggle to save humanity. Art workers are essential.

The pandemic has revealed that the vast majority of workers deemed essential are also those who are minimally compensated. People of color and immigrants have higher percentages of low wage workers, one more example of systematic discrimination. We begin by paying everyone a fair and proportional wage. This is just one proposition I am putting on the table. More work and debate lie ahead.

We move forward by demanding the world we want. Resistance is not enough. To resist is to respond to the terms dictated by those who have seized power, a conglomerate operating under the umbrella of econo-fascism,6 a network of individuals who directly use, or ignore the reality of neo-fascist tactics to cover up the final stages of a massive kleptocratic move. By fragmentation and competition, they have mishandled the pandemic. Everywhere, leaders and workers on all levels are putting out fires. We applaud their efforts as we criticize the system that have placed them on the frontlines of an emergency. Artists, art workers, and arts organizations are also victimized in this emergency. Within and through the spaces of art we can connect, think, and work together to draft a blueprint for the future right now.