The Importance of the Work: An interview with Rosamund Felsen

by Anne Ayres

This is an edited transcript of an oral history interview with Rosamund Felsen, conducted by Anne Ayres in Los Angeles on October 10–11, 2004. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

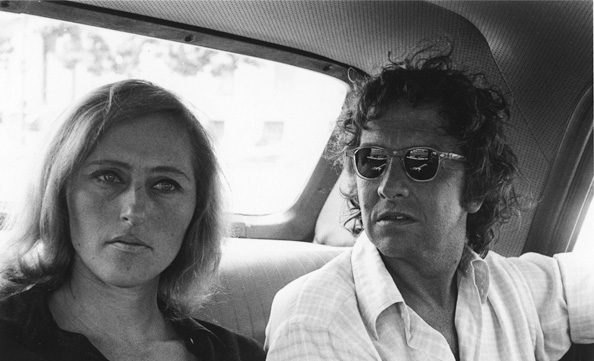

Rosamund Felsen (left) at Al’s Grand Hotel with Allen Ruppersberg, Elyse and Stanley Grinstein, Sidney Felsen and unidentified woman, 1971. Photo: Gary Krueger. Courtesy of Allen Ruppersberg and Margo Leavin Gallery.

In this interview, Rosamund Felsen describes engaging in the nascent 1960s Los Angeles art world; the founding of Gemini GEL with her husband, Sidney, and Stanley and Elyse Grinstein; working in the now-defunct Pasadena Art Museum and that museum’s downfall; starting a gallery to show younger artists making nontraditional forms of art; the financial difficulties of exhibiting Conceptual art; and the importance of art schools in forming a regional art scene.

ANNE AYRES: The general focus of your gallery was on Los Angeles artists and often on artists who weren’t getting that much attention. You seem to have wanted your gallery to be the place where out-of-towners came to see the newest and best of LA artists. Did that work out? And was that function more urgent when you started your gallery in 1978 than it is today?

ROSAMUND FELSEN: It was the exception rather than the rule in 1978. In the early days, the collectors and museum people were most comfortable with the artists with whom they had the most familiarity, the Ed Ruschas and the— I can’t say John Baldessari because he wasn’t a popular artist in 1978, but a lot of the artists from the Venice area: Billy Al Bengston and Robert Graham and those artists. Those were the ones that people were comfortable with. And in those days, the habit of Los Angeles collectors when they were going to buy some art was to go to New York. It was before the shift. Today people are most interested in finding the newest and the youngest artists. In those days it was the exception, I’d say.

AA: Let’s go back to the beginning: how and when did you become involved with the art world in Los Angeles?

RF: Well, I got married to Sidney Felsen at the end of 1960, and he had some involvement with the art community in Los Angeles. He was at that time a practicing CPA, and some of his clients were artists. And he also was very close friends with Stanley and Elyse Grinstein, who were even more involved with the Los Angeles art community, and they were at that point already starting to become serious art collectors. So through that connection we started attending gallery openings and the Monday night La Cienega gallery walks and going to museum openings. Oh, and the early Dwan Gallery—those were important exhibitions. I certainly remember the Rauschenberg and many other shows that she had. And I remember the early exhibitions at the Pasadena Art Museum, and when the County Museum of Art opened on Wilshire.

AA: There must be many people who were in your situation to some degree, just as there are today, who involve themselves with the cultural world of their community to some extent without ever thinking of being an active participant in it. I think that must have been the change for you, between being an amateur, a lover, a participator, and actually engaging.

RF: Right. And it also happened to coincide with the fact that my children had reached an age—the youngest was just starting school so I had more time. Timing is everything, and the timing on this, everything kind of dovetailed right into place.

I must have had some interest in art before—I remember that in the fifties my brother and I used to watch the Lorser Feitelson television show. I think it was on Sunday mornings. I thought he was so elegant, and he talked, giving us so much information that we had no access to otherwise.

As soon as Sid and I were married, we started going to museums and galleries and so forth, subscribing to art magazines. And KCET was having television interviews with artists. In fact, one of them I remember distinctly was Alan Solomon interviewing Jasper Johns, and I thought he was the most brilliant person I had ever heard in my life, in the art world anyway. And I thought, Oh, this is just fantastic. I was just absolutely glued to this, to everything that he had to say.

Now, mind you, I had never been to New York by 1965 either, so I had only seen this artwork in reproduction, and so to see these in person, this was a very exciting thing for me. And the scale, I remember that was a big thing for me, the scale, seeing these great big huge things.

AA: I recently saw a photograph of Marcel Duchamp in Las Vegas in 1963 seated with Betty Asher and Betty Factor and Monte Factor and some others. It would be impossible to sum up the lives of these people who were important in the development of the LA art scene, but did you know them at this time, in 1963, and were they an influence on you in any way later on?

RF: They were an influence. I can’t remember exactly what year I met them. I probably knew Betty Asher more than I knew Betty Factor, but maybe I knew them both. I think what was impressive to me was seeing Betty Asher’s collection, getting to know her and seeing how very serious she was about art and art collecting, and how knowledgeable she was, and that she was such a down-to-earth kind of person. And she had a good influence on me, I think, for that reason.

Betty and Monte Factor had another kind—they were more like patrons, I think. And while they were collectors, too, I think their patronage was so terribly important. This is something that is rare in Los Angeles. I think another example of good patrons was—I’m changing the direction here a little bit—but another example of good patronage was Stanley and Elyse Grinstein. There’s so much that they do that people don’t even know about because it’s not important to them that people know about what they do.

I’m talking about the situation where an artist wants to do a project and needs help, and they’re there to help them. It’s usually financial but not always. They do this because they want to, and they feel that this particular artist is going to make an important contribution, and they’re going to make it possible for this artist to do that.

AA: And they don’t expect to—

RF: They expect nothing. They expect nothing.

AA: With your husband, you were a cofounder of Gemini GEL in 1966. Stanley and Elyse Grinstein were also involved. How did that come about? Who was the master printer?

RF: The master printer was Ken Tyler, who had previously been a master printer at the nonprofit print shop Tamarind that was based here in Los Angeles, funded by the Ford Foundation. June Wayne was the director. Ken Tyler had been there for a number of years and decided to go out on his own. He started this custom lithography shop, and artists would come to him and he would make prints for them. But he realized that financially this was not a good way to go.

At that time he was sharing space with the framing establishment Art Services, on Melrose; he was in the back and Art Services was in the front, toward the side. I think what happened is that Stanley and Elyse had been at Art Services and they were introduced to Ken, and he was obviously looking for some kind of backing.

I had talked with Sid about the fact that he had so much interest in art, and I thought, How can he be content with just working as a CPA? I thought there ought to be something more interesting that he ought to do. He’d always thought that he provided a valuable service, and I said I was sure that he did, but there’s more. So he started thinking about different things. And then this presented itself, and the four of us got together and started thinking about ways to make something lucrative out of this print shop.

Our determination was that to be done correctly and successfully the print publishing business can only be done if you’re working with top-rate artists who have an established market. That was what would enable the business to succeed. The idea of working with these top-rate artists was that they already had representation by mostly New York, very established galleries, and also there were other galleries around the country who represented these artists as well. So there was already a built-in network of dealers, and this would be the logical way to do this. The business was begun January 1st of 1966.

Ken had already worked at Tamarind with Josef Albers, and so that seemed like a logical place to begin. At this time Josef was getting elderly and was no longer willing to travel to Los Angeles. He knew he wanted to make a series of white-line squares, and so he painted on board how he wanted the prints to be and cut each of them in half. He kept one half, sent the other half to Gemini, and Gemini would have to match the colors perfectly in lithography ink to his paint. No easy task.

Rosamund Felsen and Robert Rauschenberg, 1971. Photo: Sidney B. Felsen. Courtesy of Sidney B. Felsen.

And this whole process—there were seventeen in the series, editions of 125, as I recall—this whole process took nine months. We had printers come from Cal State Long Beach, which had a good printmaking department in their art department. So that was the beginning. The next artist who was approached was Bob Rauschenberg. He came out and he came with a friend; I think he needed a buffer zone at that time. And that was really thrilling. Bob, of course, is always interested in doing something new and innovative, and anybody who would present him with an idea of something that he had never done before, that was the most interesting thing. What had been suggested to him was that he could do the biggest lithograph that he had ever done. That ended up being his self-portrait, but the self-portrait was an X-ray, a life-size X-ray of himself. This print was called Booster, and it’s been a very important—art-historically important—print. We were able to do this because Ken figured out how to do it technically, and we were able to get the X-ray done by the husband of an old high school friend of Sid’s, a radiologist. So it was all in the family, so to speak.

Once Bob came to Gemini, that opened the door for all the other artists to come, and it wasn’t difficult to get other artists. And it was a success from the very beginning.

AA: I think you probably answered this question by implication, but I wanted to ask you to compare Gemini GEL with the Tamarind Lithography Workshop that was founded by the LA artist June Wayne in 1960. Her operation was nonprofit, which is, I suppose, the huge difference in the operation, but primarily how were they similar and different?

RF: Well, yes, it was by invitation at Gemini, and the idea was that no expense would be spared; whatever the artist wanted to do, no matter how difficult it seemed, Gemini would do it. And I suspect, although I don’t know for certain, that Tamarind probably had its financial limitations and was therefore prohibited from doing certain things. We were very adventurous. This was the heyday of Pop art and the excitement about the New York art scene and everything that was new and thrilling. Everything had to be bigger and better and flashier and more exciting, and this was how Gemini just—

AA: Yeah, and because of Pop art’s interest in replication and media imagery, the whole idea of reproduction was in the air, I think.

RF: It made perfect sense, yeah.

AA: Just as photography became recognized as a legitimate art form, it probably gave a boost to the world of printmaking.

RF: Absolutely. Yes.

And also the economics of it was that here were these very important artists who had gotten very famous very quickly, and there was a lot of excitement about beginning to collect, and many people were not able to buy paintings and sculpture by these particular artists, so prints, being multiples, enabled them to be able to afford to get works by these artists. Johns and Rauschenberg weren’t just making reproductions of their paintings; they were making original works for these lithographic series, and they were very, very innovative in their techniques. So that was important.

AA: So perhaps unlike that first experience with Albers, you tended to want to work with well-known artists who were interested in exploring the experimental aspects of printmaking.

RF: Exactly.

AA: What was your role at Gemini GEL?

RF: I started out as being the shipping clerk, and I was taught how to pack prints very carefully and ship them off. Then I worked into becoming the assistant curator. At Gemini, that means really more of a registrar, probably—but overseeing the artist signing the prints and then cataloging the prints and caring for them, and also involved with sales to a certain point.

AA: How much were you involved with sales?

RF: Very little, because I was more interested in the creative part and working with the artists and doing that kind of thing. I didn’t feel that that was a strength of mine, working in sales. I had to learn gallery social skills later. At that time I didn’t want to have to deal with people that I didn’t know, or didn’t know very well. Some of this job is about taking yourself out of yourself and working with another person and thinking about how they might be feeling about things. You always have to be trying to get things out of them rather than just thinking about yourself. I wasn’t ready to do that, and since I wasn’t needed to do that, it was not an issue.

AA: You were asked to leave Gemini in 1969 because of ongoing internal struggles with Ken Tyler. Would you talk a little about this? In retrospect, was the struggle a clue to the fact that you might want to run your own show?

RF: I didn’t know that yet. But my ego was always pretty strong, and there were things that bothered me about the way Ken Tyler ran certain things and I didn’t agree with them. In later years I probably would have kept my mouth shut and left of my own accord. But instead I chose to stand up to him, and the result was that I was asked to leave. It bothered me, it really, really bothered me the way he was doing things.

RF: Exactly. Right. It was a terrible, terrible blow to me because it meant so much to me to be there. It was a terrible, terrible blow, and I never recovered from the feeling that Sid had not really supported me in that. And Stanley. I felt neither one of them had supported me, and I thought that that was bad, because a few years later Ken Tyler left in a very angry situation.

AA: Were they unable to see what the struggle was about? It seems to me if they’re going to support one person or another, they have some grasp of the principle or issues involved.

RF: No, actually, I think that they agreed with me, but they felt that his role was more important than mine—

AA: So that’s where the hurt would really lie.

RF: Oh, sure. Oh, sure.

AA: After leaving Gemini, how did you get involved with the Pasadena Art Museum, and what did you do there?

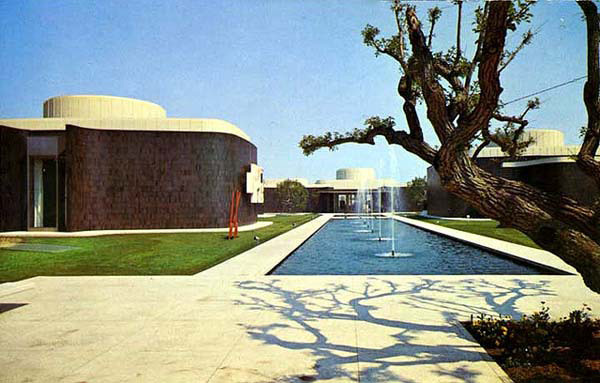

RF: I guess John Coplans, who was the curator at the Pasadena Art Museum at the time, was visiting at Gemini one day, and he was moaning and groaning about how there was so much work to do and they needed help. And they were getting ready to move from the little, small Chinese building on Los Robles Avenue in Pasadena to the new building, which is now the Norton Simon Museum, that was to open in December of 1969, and this was October. So Sid suggested to John that maybe I would be happy to work for him and help him out for a few months.

And that’s what happened. John was very pleased to have me there. This was the last year that artists were allowed to claim a deduction for a gift of art to a museum. So John was very busy going around and getting gifts of artworks from all the artists that he could find in Los Angeles—and elsewhere, I’m sure. There was also a department of photography that was headed by Fred Parker, and there were so many photographs coming in and Fred needed help. So he wanted me to come help do the cataloging of these photographs, which was an interesting thing for me because I knew very little about fine art photography. This was a great learning experience for me. In cataloging this work, I got to learn about these very interesting—these were contemporary photographers. It was not vintage or historical material.

The registrar at the museum had trained at the Museum of Modern Art, and John said that if I were to learn anything about how a museum operates, the best way is to learn registration and that I should train under her. So I did, and that’s how I learned how to do that.

AA: John himself was a critic and later became the editor of Artforum and became a very well-known photographer himself later on. What was he like to work with?

RF: Well, he was a tyrant, but I learned from him, too. He was very generous. And he decided that—I was getting more and more outspoken here again—and he decided that he needed me to be present at the meetings with the staff and the board of trustees. In order to do that, he had to make me a curator, and considering my background in prints, he decided to call me a curator of prints. That’s how things were done at small museums in those days.

AA: There were some interesting curators there during his time and after he left. You worked a great deal with Barbara Haskell.

RF: Correct.

AA: What was that like?

RF: That was wonderful. We got on very, very well. And we complemented one another’s talents. I had a good eye for installing, and she had a good mind. She was a good writer. She curated exhibitions, and I basically installed them for her.

AA: Lest we forget, what were the glories of the Pasadena Art Museum? It was much beloved at the time, and of course, I’m going to ask you next what happened. But I’d like you to just remind people what a tremendously interesting institution it was.

RF: Well, it was, because it was the only game in town. There was very little going on at the Los Angeles County Museum. Maurice Tuchman at LACMA had his big blockbuster shows every five years or so—or maybe it was even less often than that. And Jane Livingston was another curator; she did a wonderful Bruce Nauman, his first retrospective exhibition. But there wasn’t an ongoing momentum at LACMA, in terms of contemporary art, at that time.

So the Pasadena Art Museum was the place. And it was constant. It was a combination of established artists and younger artists. John Coplans did work by more established artists, and Barbara Haskell was more interested in the younger artists. That’s how it developed. I seemed to know a lot of the younger artists—how did I come to know all these young artists? I guess through Gemini; through some of the printers there, I got to know a lot of the young artists in town. So she and I would go out on studio visits together. I think with my support she put together these exhibitions.

AA: The programming was very ambitious, and the staffing was probably not up to that programming; it never is, but people do it. That can’t be the reason for its failing. Would you talk a little bit about why the museum closed, and why it had to close? And can you discuss the roles of Bob Rowan and Frederick Weisman and, of course, Norton Simon himself?

RF: This came during the recession, and I think there was a great deal of naiveté about this museum. The Pasadena folks and all the people involved—Marcia Weisman was very much involved, but she didn’t live in Pasadena—they all wanted it to grow and develop, but they didn’t make the correct financial arrangements for it. There was no endowment.

Times were changing and things were growing very quickly, and things were getting much more expensive. Their programming was getting more and more ambitious. It used to be that when the museum was short of cash, Bob Rowan or whoever else, Gifford Phillips, would reach in their pockets and “Oh, here’s some extra money for you,” you know. But that was no longer possible. So I think it just caved in because of this naive attitude. So Norton Simon, of course—

AA: Who was the brother of Marcia Weisman.

Pasadena Art Museum, ca. 1973. Courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archive.

RF: Coincidentally. I remember going to a dinner party at Marcia Weisman’s, and Norton was there. This was before the collapse. She had her Jasper Johns map painting hanging in the dining room. Everyone else at the party was in another room, but Sid and I and Norton found ourselves standing in her dining room alone, and Norton was looking at this painting. I tried to engage him in conversation about it, and he had no interest in this painting whatsoever. Later I talked to Marcia about this, and she said never, ever talk to Norton about art that was made after World War I. That’s what she said. That’s not exactly accurate but pretty accurate.

Norton had long been looking for a place for his collection—I guess he had tried to do something with LACMA, and that didn’t work out. He had had some major sculptures on loan for some time at the Pasadena Art Museum, so when the museum went to him for help he said, “Well, I can help you. I’ll take over your debts for you; I’ll take over all the debts for you if you let me take over the collection in the museum, and you won’t have any further responsibilities there.” I mean, this went on for—there was lots of going back and forth, but that’s how it ended up.

AA: What happened to the Pasadena Art Museum collection after he took over?

RF: Well, the first thing he wanted to do was to get rid of the collection of contemporary art. He started putting it up at auction, and some of the former trustees, Bob Rowan and Alfred Esberg, put a stop to it. They got a restraining order, prevented him from being able to do that. So the work is still there.

AA: I remember—it must have been in the late eighties—going into their storage and seeing works by—famous works now by, say, George Herms and Bruce Conner—

RF: Absolutely.

AA: —that were just under sort of bubble wrap pushed in the corner. Since that time they’ve been lent to LACMA and MOCA—

RF: That’s right.

AA: —which seems to me the reasonable and right thing to do.

RF: Which is what they had done, and I think that arrangement has worked out very nicely. Finally. But it took a long time for that to happen.

AA: And of course they had the Galka Scheyer collection, and that they have paid a great deal of attention to.

You left the Pasadena Art Museum in 1974. Why?

RF: Well, the handwriting was on the wall, and the museum was about to close. Norton was ready to take over, and it happened to coincide with Ken Tyler’s decision to leave Gemini, and there was a big lawsuit, and they needed me back. There were certain things that Ken had always done that they didn’t know how to do, but I did. For example, printing their advertising publications, brochures—for every publication that Gemini puts out there is a brochure.

AA: Had the museum experienced changed you?

RF: Yes, it did. I had a lot more experience now and—oh, yeah, the registration experience really helped me a lot.

AA: So John was right?

RF: Yeah, he was right. I created new documentation sheets for Gemini and for the whole print world actually. A documentation sheet specifies each and every aspect of the print and authenticates it and everything; it’s signed by the artist and by an officer at Gemini. And I was just generally the public affairs person; that’s sort of what I did.

AA: And there were also changes in your personal life now?

RF: In 1976 Sid and I decided to divorce, but he and Stanley, the remaining partners, asked me to stay on. This seemed like an impossible thing to do, so I just left.

AA: You considered going to school at UCLA, but instead decided to work for the Timothea Stewart Gallery. Who is Timothea Stewart, and how did your involvement with her gallery come about?

RF: Well, same thing happened again. There I was at home, and Timothea Stewart came and visited Sid at Gemini and said she was about to open a gallery and did he know anyone who could come and work for her? He suggested me again. So she called me. I barely knew her; her father had been Bart Lytton, who had been a successful savings and loan person in town and was also an art collector. He gave a lot of money to LACMA; his name was on the building at LACMA that is now the Hammer Building. But due to one of those recessions when savings and loans went into difficulties, he lost his money, and therefore they took his name off the building and gave it to Armand Hammer instead.

He was a very flamboyant character, and Timothea was an only child. At this point he had died, and her mother had just died, I think. She was out on her own, but she did have some money and she decided that she wanted to open this gallery. The gallery that she wanted to open, the space was formerly the Riko Mizuno Gallery, and it was just this really precious little gallery on La Cienega that everybody loved. She was going to open with a Wallace Berman exhibition.

This was in April or May of 1977, and she wanted to open in May, I think it was, and I was supposed to be going to UCLA that September. I was all accepted and everything, all set. I said, “Well, I’ll help you out for the summertime.” The combination of the Wallace Berman show and that space—I thought it was just too nice to pass up.

I went to work there, and I was the person there, she would show up at 4 in the afternoon for 15 minutes or so. I didn’t know the first thing about selling anything, and Wallace Berman wasn’t exactly a big seller in those days. Many people didn’t even know who he was. And this, of course, was after he had died. She had a spiritual connection with Wallace Berman; that was what her interest was. The exhibition was up for five months and nothing sold because I didn’t have a clue of an idea of how to go about selling anything; I just kind of sat there. Then at the end of five months she decided that we would have a second show, and the second show consisted of artworks that she’d got on consignment from Bob Rowan, who was a friend of hers. There were some big Larry Poons paintings and other big color-field paintings, and I didn’t sell anything there either.

Oh, I left out the part about why I didn’t go back to UCLA. I don’t know, I just felt comfortable in the situation. I felt I didn’t need to go to school; I needed to be in the gallery. I enjoy the artist community, you know, all the local artists that I’d gotten to know from working at the museum.

The second show went up and that was up for four months and nothing sold. And then she decided that she was going to close the gallery. She’d done what she wanted to do. She had wanted to have this Wallace Berman show and that was it. And everybody said, “Oh, Rosamund, you should take over the gallery.” Me? Take over the gallery? Everybody’s telling me that I should do this, and I said okay. So I took over the gallery.

Rosamund Felsen Gallery, 1986. Back (L-R): Leland Rice, Lari Pittman, James Hayward, Karen Carson, Grant Mudford. Middle: Chris Burden, Steve Rogers, Richard Jackson, Alexis Smith. Front: Renée Petropoulos, Jeffrey Vallance, Rosamund Felsen, Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy. Paintings by Paul McCarthy. Photo: Jim McHugh. Courtesy of the Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

AA: Well, we have reached 1978 and your gallery. I wanted to ask you, first, what were [your] personal experiences of important Los Angeles galleries in the fifties, sixties and seventies—the gallery scene that preceded the opening of your gallery? Ferus’s place in history is pretty secure, but there was also Virginia Dwan—you’ve spoken about that—David Stuart, Nicholas Wilder, Molly Barnes, Eugenia Butler, Rolf Nelson, Riko Mizuno, Gagosian. It was a small world, but a lot was happening.

RF: And Felix Landau.

AA: Yes, there are many more.

RF: Yes, yes. And I think probably that the two galleries that impressed—well, aside from Dwan, but that was long closed—were probably Eugenia Butler and Nick Wilder. I was most interested in Eugenia Butler’s artists and the art that she showed. Nick had a scene going on there that was interesting, and he was such a wonderful person. He was just really great to spend time with and to talk with about art. His sensibility was not my sensibility at all. But that didn’t matter because I liked him so much.

AA: Molly Barnes.

RF: And Molly. Well, Molly—I always think of Molly as showing joke art.

AA: But she showed John Baldessari—

RF: But she showed Baldessari. Yes, she did. And there are some jokes in John’s work.

AA: Would you describe the La Cienega space in some detail as to who helped design the space? I particularly remember a magical sense of light, and I have a trace memory, perhaps false, of the color blue. I think it must have been the light.

RF: That was the blue sky that was coming through.

AA: That was the sky. That was the sky.

RF: Sure. When Riko had the gallery—well, first it was Rolf Nelson. No, first it was Esther Robles, then it was Rolf Nelson. When Rolf Nelson had that gallery—this was in the early sixties—I remember seeing my first Georgia O’Keeffe painting. He had put in a parquet wood floor, and in fact, one of the people who put it in for him was Joe Goode, who was a young artist at the time. Then when Riko had the gallery she had an Ed Moses show. Ed decided that there should be some natural daylight coming in there, and he said, “Why don’t we just take off the roof?”

So they took the roof off, and he had this exhibition, and I’m sure leaves were blowing in, whatever, but it didn’t matter. Riko started getting nervous about the landlord—“what if the landlord comes and he sees the roof is taken off?”—because they went ahead and did this without his permission, of course. Then Bob Irwin, another artist that she was showing at the time, said, “Well, wait a second. Before you put the roof back in, let’s put some skylights in.” So he designed these, as I recall—they’re two 14-foot-long-by-2 ½-foot-wide skylights. The proportions of the room were almost— As Keith Sonnier said when he first saw it, it was almost like a golden section; it was just such a perfect proportion, that space. Beautiful space.

AA: Beautiful.

I was going to ask you how many of these galleries were clustered on La Cienega Boulevard. But I also get the sense that chronologically this space was a cluster, that it housed a series of galleries. But there were other galleries, and of course, we’re talking about the fifties, the sixties, and the seventies. That’s a big spread. La Cienega did have a critical mass of galleries up and down the block.

RF: Yes, before I was there actually. By the time I got there the major galleries were no longer there. Do you know that I had forgotten that Larry Gagosian was in that space? That’s interesting.

AA: I believe the artists you showed in your first year were Guy Dill, Keith Sonnier, Richard Jackson, Peter Lodato, Alexis Smith, Maria Nordman, and Bill Wegman. Not one of these is a traditional painter or sculptor. One or another of them touch on light-space art, appropriated text, photographs, or other nontraditional or conceptual gambits. Did that reflect the current situation, or were you drawn especially to what was then experimental art?

Rosamund Felsen with Richard Jackson’s Big Ideas, 1984. Courtesy of the Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

RF: Well, when I started the gallery, there were all these floating artists around because their previous galleries had closed. Alexis Smith had been with Nick Wilder; he was closing. Claire Copley had been around a while, and she was closed. I don’t know that I had a particular direction; it was just, you know, art that I was interested in and that I felt needed to be shown.

AA: Your second year saw a tremendous event, which was the showing of Chris Burden’s Big Wheel in 1979. How did that come about?

RF: Well, Chris just came walking in the door one day and he said he has this new piece. You know, for many years Chris had just been doing performance. He had shown his relics at Gagosian in that same space, and then the following year he had shown his Full Financial Disclosure with Jan Baum. But he didn’t really have a home; he didn’t really have a place. So he had this new piece that he wanted to show with me, and was I interested? I said sure, and so he invited me down to his studio and I saw the Big Wheel, and he put it in motion.

I had enormous respect for Chris, and maybe somebody else would have been nervous about showing this because it looked like it could be dangerous. But I trusted him because I knew how smart he was. I knew that he knew what he was doing in terms of mechanical things.

AA: Yes, I’ve always thought of Chris as something of a magician in the sense that he’s always very careful and assured about what his effects are going to be. Many of them were dangerous, but if they involved, say, fire he would be sure to cover himself with Vaseline or something like that. I think in that sense he was trustworthy.

RF: Absolutely.

AA: Did you see any of those early performances that live mostly in documentation and legend?

RF: No, I never saw them. Oh, but one of my favorite ones—I forget what it was called—was when the Contemporary Art Council from LACMA came for a studio visit, when he was in Venice. They knocked on his door, and he opened the door and invited them to come in. There was nothing really for them to see, but he sat down at his desk and made some notes, and then he gets up and makes some coffee and goes back to his desk. Then he gets up and goes to the bathroom and then he comes back. Oh, I left out an important part. When they came to the door, he asked—he demanded—that they each pay him a dollar, and they were outraged because they had already paid for this trip. But, you know, if they want to see an artist, what an artist does in a studio, he was showing them.

AA: Chris was among a number of soon-to-become important artists who chose to remain in Southern California rather than build a career in New York. Can you pinpoint a time when there seemed to be a critical mass of important artists pursuing successful careers in Los Angeles?

RF: That didn’t really happen until the late seventies, early eighties, and it just happened to coincide with when I had the gallery in the early years. I think it was because it was getting more and more expensive in New York for artists to go there. There were more jobs for artists in Southern California because of all the art schools. And it was easier to get work done in LA.

AA: The decade of the seventies in your life encompasses the last years at the Pasadena Art Museum, the brief return to Gemini, the opening of your gallery in 1978, and its first two extremely interesting years. The seventies saw the explosion of Conceptual art and site-specific art and architectural sculpture and, generally, art of an ephemeral nature even in materials or duration. How does a dealer in art survive in such a climate and how do the artists survive?

RF: Well, either you’re rich, which I wasn’t—I had some finances behind me but not a great deal, and I didn’t want to squander them—or you learn that you have to have a certain relationship with the collectors.

Now, in those early days when I first opened the gallery, I was fortunate in that the art world was pretty small. I knew all the artists. I knew all the museum people. I knew all the writers. I knew all the collectors. Everyone knew everybody. People were happy that I opened this gallery because, as I mentioned before, many of the other galleries had already closed. And they loved the space. People loved it. They thought it was charming, you know.

So I had to learn how to talk about the art to collectors. I was used to talking about art with artists, but talking with collectors is different. This was before people started thinking about art in terms of an investment, so what you had to do was talk about the importance of the work.

AA: We were talking about Conceptual art and how a dealer survives in such a climate, and possibly even more to the point, how the artist survives.

RF: Yeah, well, the easy part is for the artist if they’re lucky enough to get teaching jobs—and that’s another story about why Los Angeles has become such an important art center; it’s because of all the wonderful art schools here that are staffed by, you know, this incredible faculty of artists. This in turn attracts young art students who want to study with a particular artist, and before you know it you have this burgeoning art community, which is what we have now.

In answer to your question about how does the gallery survive. Well, in my case, when the likes of Mike Kelley came walking in the door and wanted to know if I was interested in showing him, I said sure. He said he wanted to show—I think this was in November of ’82. I’m just guessing it was about that month. And he said he wanted to show in February the following year, which is, like, in three months. And I said sure. I didn’t have a slot in February, but I had seen a little bit of Mike’s work. I had seen—more important, I had seen one of his performances, and I thought he was brilliant, and I just changed my schedule. And I thought this was too important to pass up.

And along came Bob Rowan, who I had known, of course, from my Pasadena Art Museum days. He had been a big proponent of color-field painting and New York artists, and that’s what he was collecting, although he did also collect Nauman, which is kind of a contradiction. But he just became very enthralled with Mike Kelley’s work and he saved my life. He helped me keep my doors open because he was interested in what I was doing. He bought a lot of Mike’s work; for a number of years he was Mike’s biggest collector.

AA: In the 1970s many site-specific installations and performances also were presented in a remarkable number of alternative and university or college art galleries with extraordinary, prescient curators or directors. Would you say a little bit about Bob Smith at the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, LAICA?

RF: Well, it wasn’t really until after he was gone that I really appreciated—I think I just took him for granted—that this was an alternative space and that’s what alternative spaces do. And then when he was no longer there, I realized that the alternative space is only as good as its director or its curator or whoever’s in charge of the program. All it takes is one person. The same thing happened when Joy Silverman was at LACE.

I think what happened with LAICA was that Bob Smith used to travel so much—and he used to bring so many foreign artists here, too—and that was very important, not only for the community here to see the work, but the influence that it had upon the artists working here.

AA: Then also in the seventies there was the work of Hal Glicksman at Otis—wonderful Conceptual exhibitions of On Kawara and Daniel Buren, for instance. Could such difficult exhibitions, which would bring prestige but no sales, have been held in a commercial gallery?

RF: I think that museums should be doing that kind of thing.

AA: I could also mention Melinda Wortz at Irvine, Michael Smith at the Baxter Gallery at Caltech in Pasadena, Dextra Frankel at Cal State Fullerton with their intensive exhibition-design program, Betty Gold at ARCO Center, Josine Ianco-Starrels at Cal State Los Angeles and then at the Municipal Gallery.

Do you have any particular memories of their programs? Were the majority of commercial galleries in LA as responsive to Los Angeles artists in the 1970s as many of these places were?

RF: No, I don’t think they were. And Josine had a remarkable energy.

AA: All of this art activity was against the background of the Vietnam War and the antiwar demonstrations and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy in 1968 and Stonewall, 1969, in New York, which was the beginning of the gay and lesbian rights movement, and of course, the women’s movement. Were you involved in any way in the women’s movement?

RF: Only secondhand, through some of the artists in the gallery. But you know what? I was never invited to participate. I thought it was curious that they didn’t invite me. Maybe because they thought I was like a married person with children and that maybe they were different sorts—

AA: But with a career—I mean, isn’t this for you?

RF: Well, this was going on when I was at the museum. I don’t know. It’s interesting that they never invited me—I never was. If I wanted to participate I suppose I could have asked, but I didn’t. I don’t know why.

AA: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party opened in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979. That’s one year after you opened your gallery. Were you aware of Judy Chicago? Of course, you probably were from Maurice Tuchman’s show [“American Sculpture of the Sixties,” LACMA, 1967], too, when she showed those early minimal pieces.

RF: Well, not only that. Judy was a very close friend of Elyse Grinstein, and so I saw Judy often. The most important thing that I remember in the early days with Judy is that she was the first person I heard who ever said anything about the Palestinians in relation to Israel. And I thought, Ah! I’d never thought about that before. I still remember that.

AA: CalArts opened in 1971. It takes time to build a graduate program. However, many of your artists in the 1980s, while you were still at the La Cienega Gallery, received MFAs in the years more or less between 1976 and ’82: Mike Kelley, Lari Pittman, Roy Dowell, Marc Pally, Jim Shaw, Tim Ebner, Mitchell Syrop, John Miller. Would you discuss the impact of CalArts and why it was so successful?

RF: I think that it has to do with the faculty. And probably the strongest influences were certainly Baldessari and Michael Asher, and the visiting artists that they had teaching there over the time. This attracted the most interesting students. I remember Mike saying that when he wanted to go to grad school, he could have gone to New York, but he didn’t want to live in New York. He wanted to come to California. And CalArts was the only game in town.

AA: In 1981, LACMA devoted two simultaneous exhibitions to Los Angeles artists. Maurice Tuchman curated “Art in Los Angeles: Seventeen Artists in the Sixties,” an exhibition that officially anointed the artists whose work brought attention to LA in that decade. Some of those artists were Larry Bell, Billy Al Bengston, Wallace Berman, Ron Davis, Joe Goode, David Hockney, Robert Irwin, Craig Kauffman, Edward Kienholz, Ed Moses, Bruce Nauman, Kenneth Price, Ed Ruscha, Peter Voulkos, and also Richard Diebenkorn, Sam Francis, and John McLaughlin.

RF: That is quite a list.

AA: Is it no accident, given the disposition of the sixties, that all of these artists were men? Do you remember the demonstration on opening night when women wore masks of Maurice Tuchman’s face to protest the exhibition?

RF: That was great. That was great. Now, was that the same time when they had the show “Museum as Site: Sixteen Projects”?

Protest at County Art Museum, July 16, 1981. Photo: Anne Knudsen/Los Angeles Herald-Examiner Collection. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library.

AA: That was the same time.

RF: That was Stephanie Barron’s show.

AA: That was Stephanie’s show. Maurice Tuchman was a force in LA art, in the LA art world for about three decades. Is a position of power like that bound to be controversial?

RF: Well, when it’s someone like Maurice Tuchman, it’s going to be controversial. I mean, someone could be beloved, too, but Maurice had such questionable operational tactics that I think that was the problem. Everybody was aware of it, and it took a long time for the museum to do something about it. But you can’t deny that his blockbuster exhibitions were quite remarkable.

AA: Going back to “Art and Technology.”

RF: And “Art and Technology.”

AA: Yes, Stephanie Barron’s companion exhibition to Maurice’s exhibition was “The Museum as Site: Sixteen Projects,” which seemed to sum up in 1981 the importance of site-specific art in the 1970s. All the installations were sited throughout the museum and in its park. Did you feel that her show was groundbreaking for the museum?

RF: Yes, I did. I had how many artists in the show? I had a number—Richard Jackson and Chris Burden, and the only two women, Karen Carson and Alexis Smith.

Richard Jackson was, and is still, under-recognized here, but he is one of these artists who has got more recognition in Europe. He decided some time ago that he was no longer going to show in Los Angeles because he wasn’t getting the support, which is what happened to Kienholz for a while but then that changed.

But at any rate, Richard had some bitterness because he wasn’t getting the kind of support that he should have gotten, and part of that was because he wasn’t a schmoozer and he didn’t network—and was a very likeable, wonderful person. He was close friends with Bruce Nauman, and I think his work was very much influenced by Bruce, but then it started taking its own direction.

We had several shows with him, but the most memorable one for me was the one called “The Big Wall.” No, it wasn’t called “The Big Wall”; it was called “Big Ideas.” And what he did was to have a number of canvases that he actually made and stretched in the gallery. I gave him the gallery for a month to do this. These canvases were about maybe 20 inches by 30—something like that—and when he got ready to install the piece, he applied paint in an abstract way to the surface of the canvas and put it on the floor. Then he would do another one and put it facedown on top of the other canvas while the paint was still wet. He continued to do this in a long row, building it up higher and higher and higher until it came to just a foot from the ceiling. It extended from one end of the gallery to the other, but left enough space so that you could walk around it. It was fantastic.

Then he installed an iron gate at the entrance to the gallery space and gave me strict instructions that I wasn’t to allow William Wilson [the art reviewer for the L.A. Times] to come in and see the show. This was because he had not reviewed him before. And as it turned out, Bill never came to the show anyway, so it didn’t matter.

AA: Before we end I want to talk a little bit about collectors because [collecting] such an important component of what you do. A selected list of collectors who might have been important—who have been important to Los Angeles either in the past or present—would include Robert Rowan, Betty and Monte Factor, Stanley and Elyse Grinstein, Michael Blankfort, Sterling Holloway, Fred Weisman, Marcia Weisman, Bill and Merry Norris, Melinda and Ed Wortz, as well as Joel Wachs, Peter and Eileen Norton, Clyde Beswick, Dean Valentine, Lorrin and Deane Wong, Barry Sloane, Gary and Tracey Mezzatesta, George Wanlass. How many of these collectors—and you could certainly add more, I’m sure—were or are regulars at your gallery, and how often, and whom do they buy, because we often hear that LA doesn’t have a big collecting base, and it seems to me that—

RF: Well, if that’s all there is for a city this size, it’s not very many.

AA: How many of these people were regulars in the gallery?

RF: All of them except for the Factors, I think. Every one of those. Unfortunately, Bob Rowan is no longer with us. Clyde Beswick is no longer collecting. But the rest of them, I see them all.

AA: What is the role of those who collect art on a much smaller scale, who follow, perhaps, one or two artists or who buy only occasionally a particular work that strikes them? It seems to me that these could be— These are an important collecting base for you, but they also could be a very difficult—

RF: It’s not difficult, no. It’s our bread and butter, actually. These are people who are buying modestly because they have modest means with which to buy art. We have to rely on these people.

And then sometimes somebody will come in and will say, “I’m just starting to get interested in collecting art, and can you guide me a little bit?” That doesn’t happen very often, but it does occasionally. Someone who was in just the other day, who I had helped. He bought Grant Mudford and then he bought Mitchell Syrop. How’s that for a stretch? And now he’s thinking about Kim MacConnell.

But people just beginning to collect have concerns. They need to think about things like running out of wall space. Well, that is the last thing a seasoned collector thinks of, you know? Either they put things in storage or they put things in a closet or they rotate things or something like that. That is never an issue. The issue is, they want to acquire a work of art because it has special meaning for them, there is the excitement of being a participant in the development of an artist’s maturity, and they want to participate in this. It’s all of these things that inspire people to collect. But the modest collector is important. And, you know, they could win the lottery, too.

AA: Well, would you speak about the role of groups that help fund exhibitions, such as the Fellows of Contemporary Art and the Pasadena Art Alliance.

RF: Well, the Pasadena Art Alliance, they’re such a wonderful group of women, and they have just done great work over the years in being willing to support things that might be a little risky, you know, in some people’s minds. But they trust the curators, or whoever approached them, and they go ahead and do it.

The Fellows I think have done also a remarkable job. They’re more of a real social group; they like to go on trips where they visit museums and collections in other cities and countries. What they really do that’s quite wonderful is support exhibitions with wonderful catalogs and support California art at various museums.

AA: Would you talk a little bit about Vivian Rowan and her position in the art world and the importance or consequences of art-world socializing? There seems to be an interesting intersection between the social and cultural world.

RF: Yeah, this is true. Vivian Rowan is the widow of Bob Rowan, and I think a remarkable thing is, she does not drive. And since she was on her own, she began to miss being part of the social thing she enjoyed when Bob was around, and she had this idea of putting together these dinners. Actually, she was doing these dinners even when Bob was alive, but then decided it was even more important to continue them, inviting some of us who have been around for, you know, 20, 30, 40 years and getting us together, and then gradually including newer people, younger artists, younger people, and to—oh, I think 50, 60 people.

This happens twice a year. She organizes the whole thing, and it costs $25 for everybody to go and anybody can go. It’s not an exclusive thing. I mean, she tells me if there’s anyone that I think would be interesting to come, you know, please invite them and have them come and send in their $25 check.

AA: How important is this socializing in terms of forwarding an artist or a curator’s career, specifically her parties? I mean, I know artists or people who think it may be important, but I myself would answer not very—that all of these connections have been made already. Some people are always somewhat suspicious about in-group socializing, but it’s a natural part of living.

RF: They are part—some of the people who go regularly to these dinners are people who are in a position to be able to fund certain things. They are patrons, and if they get to know people—you know, curators or artists—and feel comfortable with them, feel that they’re doing something worthwhile, then they would be happy to contribute in any way that they can. So there is that.

Rather than just having a businesslike relationship with everyone, it’s much more comfortable if you have a social relationship because the art world— I mean, it took me a while to understand this, but in a gallery situation you never know who’s going to come walking through your door. And I have learned that it is essential to have a social relationship with the people who come in. It’s not like we’re working in a department store.

Art is a very personal thing and it affects one emotionally as well as intellectually, and it’s expensive. You know, it’s not like buying a pair of shoes or not even like buying a car, although people talk to me about buying cars all the time because they know I’m such a car person. I learn all about people’s private lives and everything because of this kind of relationship that seems to be essential as part of the art world.

This is an edited version of a much longer oral history interview in the public domain. To read the entire transcript click here.