There Used to Be Vacant Lots

by Fiona Bryson

Shoot from Santa Monica Boulevard, Ed Ruscha, 1974. Roll 8: Sweetzer headed west: Image 0134. Part of the Streets of Los Angeles Archive, The Getty Research Institute. © Ed Ruscha

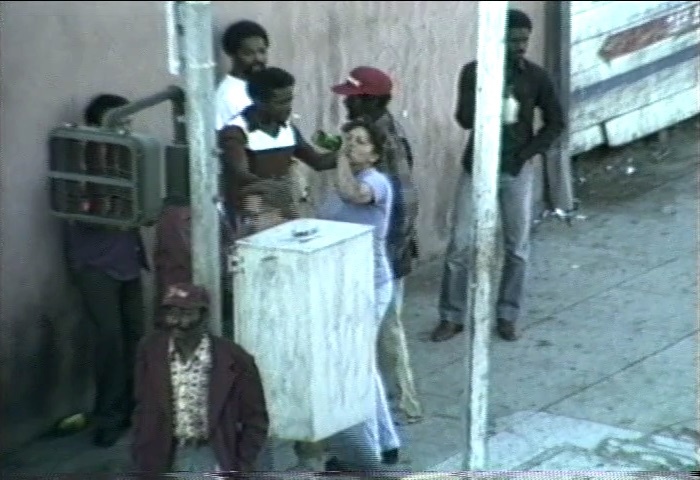

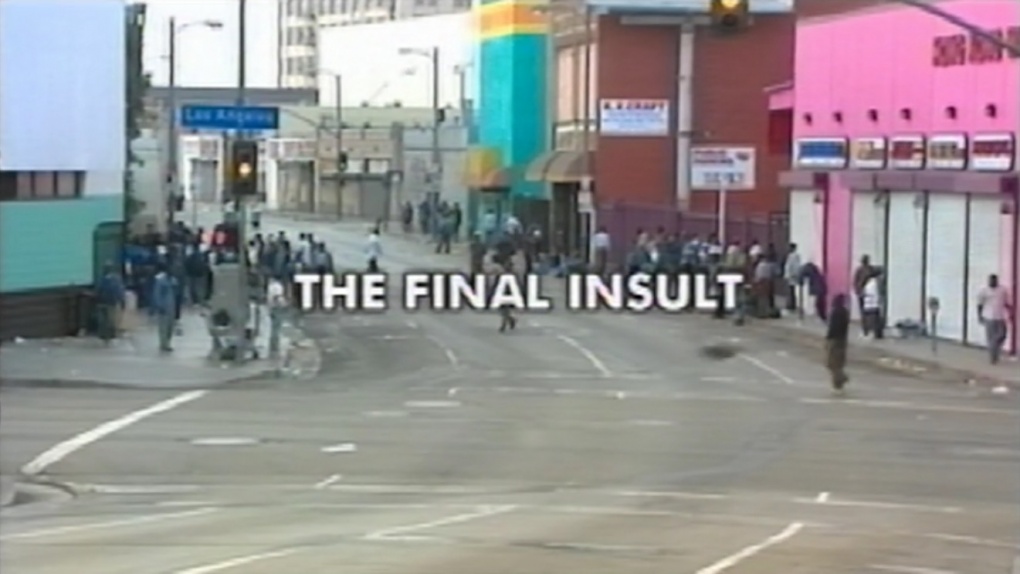

“If a whale beaches itself, the world cries out. Everyone will do whatever it takes to get it swimming in the sea again. When I was washed up everyone looked the other way.” Charles Burnett—maker of the seminal film Killer Of Sheep (1978)—uses these lines to open his 1997 short film The Final Insult, depicting the life of a fictional African American bank manager who lives in his car because he owes back taxes to the IRS, which among other things has ruined his financial status. Set in 1990s Los Angeles, the film mixes scripted scenes with documentary, featuring a cross-section of actors and people living on the street, one of whom describes how the American debt-system can quickly lead to poverty:

You have a number of people who are maligned because of their activities, primarily drugs and alcohol. And that is understandable in this particular vein, in that we as Americans are accustomed to immediate gratification. If your wife wants a washer and dryer, you don’t endeavor to save $900. What you do is, you go to Sears or Mucky Ward’s [Montgomery Ward’s department store] and you put it on the plastic and they ship it out the next day and you pay in increments. I mean, this is just how we are accustomed to doing things.1

Another man is interviewed next to a freeway exit at Alvarado Street off the 101, where a camp of unhoused people was cleared that morning (presumably by the city, before filming took place): “There’s something wrong with America today and how it’s helped its veterans and people on the street. America can send millions of dollars abroad helping other people with their homelessness problem and their economic structure.” He goes on: “Why can’t we help our own people, here in the United States? We’re in dire need of help here. […] People, wake up.”2A woman who has lost her home, belongings, and medication in the clearing of the camp explains that her husband passed away recently and she has children. Distraught, she is, however, lucid, stating that she and her friend are not drug users like those in a camp nearby, but need their home and life back. She asks the interviewer, “Will you help me? Huh? … Ha, I don’t think so.”

Charles Burnett, still from The Final Insult, 1997. Video, color, 55 min. UCLA Film & Television Archive.

With its history of homelessness dating back over a century, Los Angeles has been populated by street dwellers since before the Great Depression. The area downtown known as Skid Row originated in the 1880s, when it was home to mostly working class, white peddlers from the Midwest. As the population of Los Angeles grew from 100,000 in 1900 to over one million by 1930, African Americans from the South, seeking fair opportunity, and Mexican immigrants driven north by the Mexican Civil War added to the steady increase of Skid Row’s density.

During the Great Depression in the 1930s, the area solidified as a low-income neighborhood, becoming a place for seasonal laborers, “single room occupancy” hotels (SROs), and saloons. By the 1970s, the racial demographic had shifted to primarily Black and Latinx, and in the 1980s, following severe policy cuts by the Reagan administration and widespread deinstitutionalization among the state’s mental health facilities, Skid Row had graduated to a mass containment zone for the unhoused and mentally ill.3 Of the roughly 66,000 unhoused people in L.A. County today, around 41,000 are located in the city itself, with approximately 8,000 in Skid Row. A 2021 report on the homelessness crisis by UCLA’s Luskin Center for History and Policy states: “The affordable housing crisis, rising unemployment rates, the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill, and the deterioration of the social safety net over the 1970s contributed to what many have described as the ‘new homelessness’ of the 1980s. This phenomenon assumed particular form in Los Angeles County, which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development dubbed ‘the homeless capital of America’ in 1984.”4

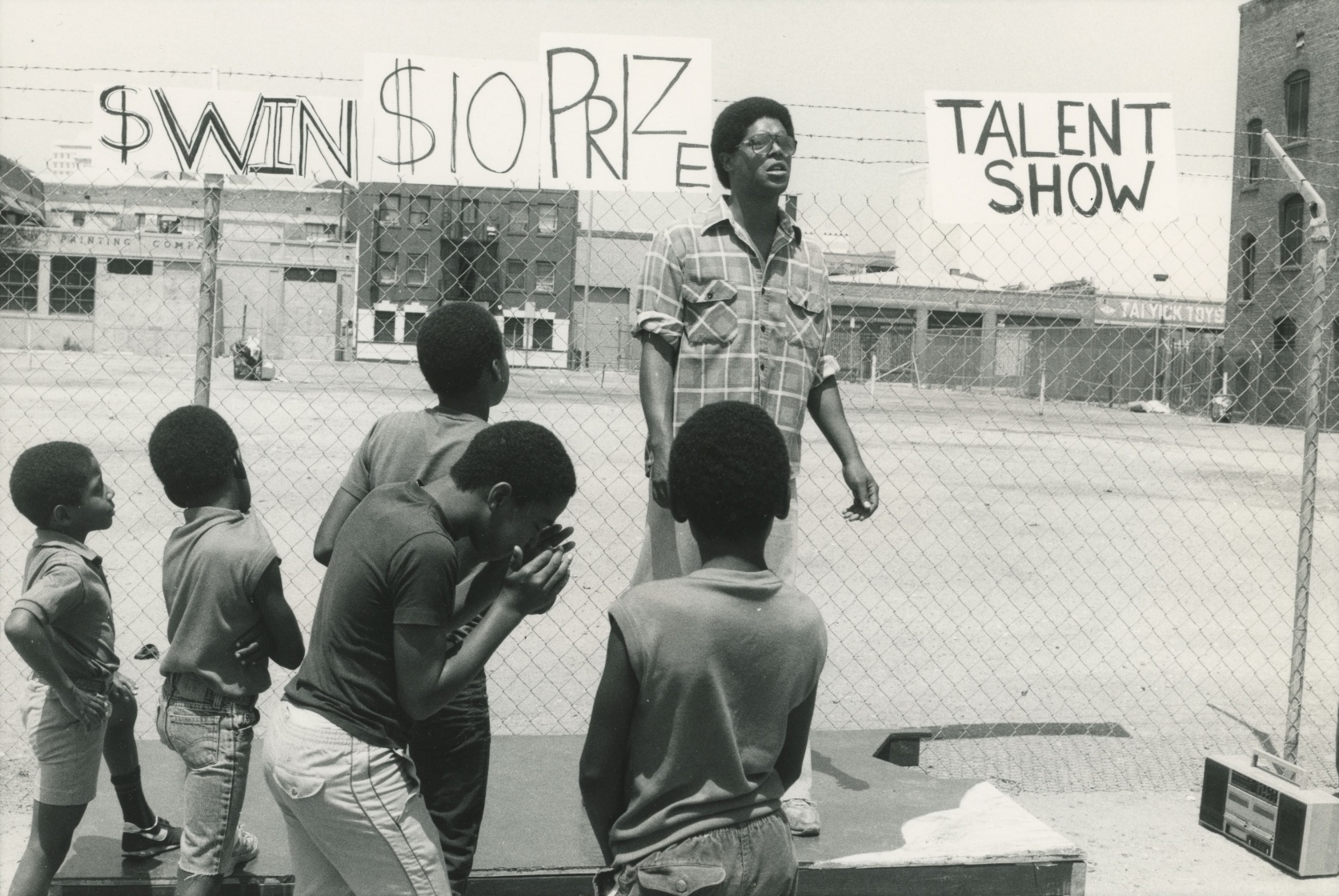

Actor and Los Angeles Poverty Department’s Assistant Director Kevin Williams performs at 5th and Wall Street for a group of children from Skid Row, Los Angeles, 1985. The first arts program of any kind for houseless people in Skid Row, LAPD produced frequent talent shows in the area and has continued to be active since its founding by John Malpede in 1985. Open to all, LAPD performers included houseless artists and other artists and locals living in and around Skid Row. Photo by Axel Köster. Courtesy of Skid Row History Museum and Archive.

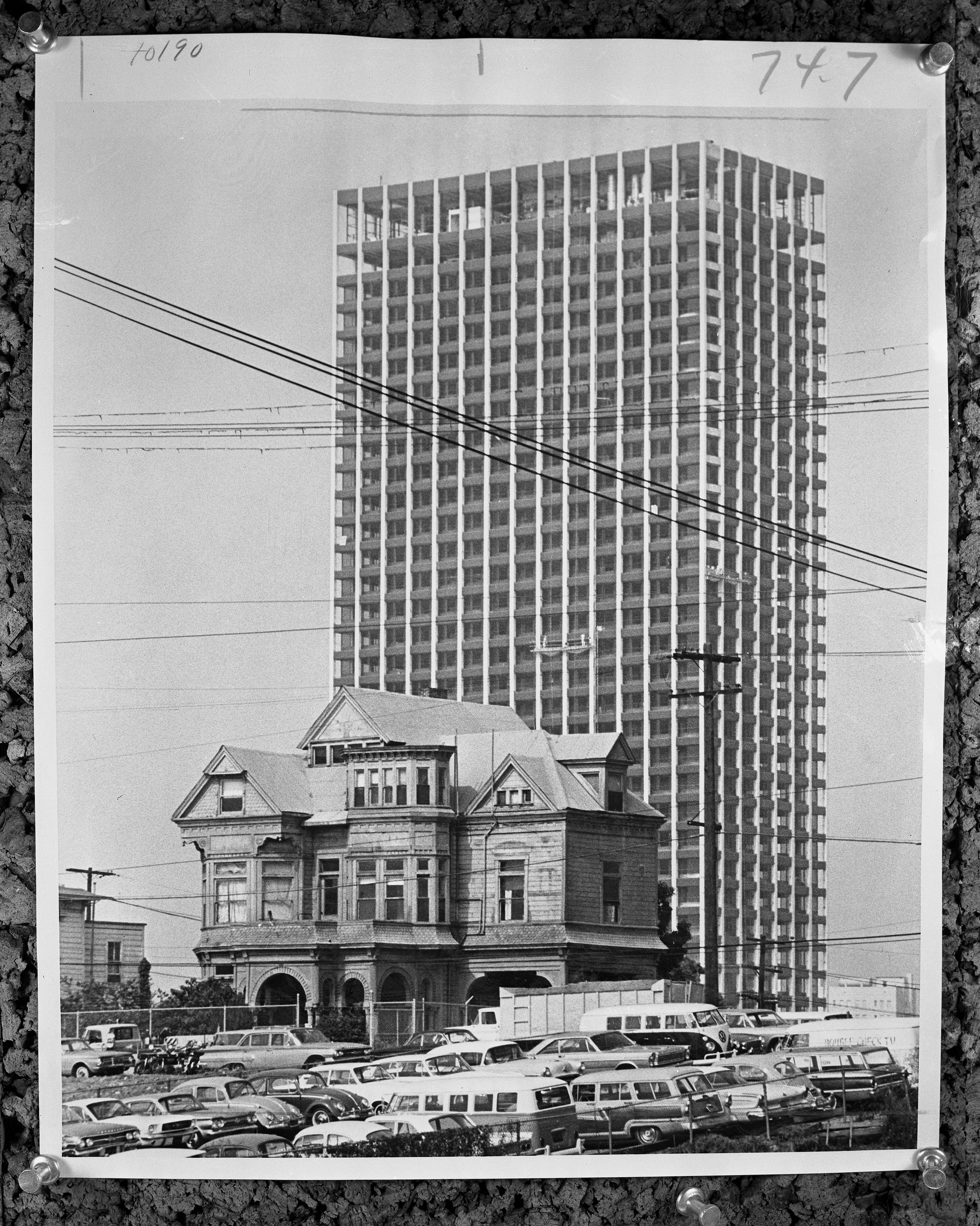

The explosive growth of Skid Row in the 1980s, simultaneous with the dismantling of the welfare state under Ronald Reagan, was preceded by the erasure of downtown’s Bunker Hill neighborhood. The ensuing commercial redevelopment moved affordable housing away from the city’s center, further increasing the racial and economic segregation already prevalent in L.A.’s DNA. In City of Quartz Mike Davis writes, “[…] according to the L.A. Coalition to End Hunger and Homelessness, the number of people living in ‘high poverty’ in Los Angeles doubled during the 1990s.” It was then considered “the nation’s poverty capital,” which “continues to house the poor in the street […], and the mentally ill in jails.”5

The crisis visibly took another turn between 2020 and 2021, as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded, with houselessness growing beyond Skid Row and engulfing neighborhoods city-wide. Tent communities exploded in Hollywood and Venice and sprawled as far as Eagle Rock and the L.A. Harbor. The encampment at Echo Park Lake became a particular focal point for discussion in 2020, engaging nearby residents and activists in a heated political debate over repercussions for the park and the encampment’s removal, until its eventual demise in 2021, caused by the city’s order for clearance. Park residents were offered housing by the city, but most received only temporary shelter and then likely moved elsewhere. Echo Park was used by local politicians as an example for the remediation of a localized houselessness issue, but did not affect change on a larger scale.6

Bunker Hill Victorian house called “The Castle” standing in front of the Union Bank building, Los Angeles, 1966. Built in 1882 at 325 S. Bunker Hill Ave., “The Castle” was declared a historical and cultural monument in 1964. It was demolished in 1969. Photo by Bruce H. Cox for the Los Angeles Times. Courtesy of UCLA Library, Special Collections.

As luxury real estate development sweeps through Los Angeles, it is all the more ironic when a camp sits next to a housing site that a majority of citizens cannot afford. Studio apartments in and around Skid Row currently rent for $2,000-$3,000 per month, and prices ascend dramatically from there. Many new luxury apartment complexes—criticized for their low quality and tasteless aesthetic—sit empty as housing prices continue to soar and adjacent tent communities are moved from one fleck to another. The unhoused cannot speak for themselves because society deems them marginal, and so the cycle of property investment benefitting the upper echelons is never broken.7

When considering vacant space in the city, Senga Nengudi’s late 1970s public installation and performance work comes to mind. Appropriating a disused area under a downtown L.A. freeway bridge, in Freeway Fets and Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) Nengudi incorporated elements of ritual and community, the earth, and the body to redefine the area’s meaning. Called “environmental sculpture,” the relatively obscure works were performed by Nengudi and members of Studio Z, a collective of Black conceptual artists—including Nengudi, David Hammons, Barbara McCullough, and others—at a time when they were largely excluded from the art world.8 Both works utilized unwanted space to draw attention to land that was of no cultural importance. As art historian Amelia Jones has noted: “Nengudi and her colleagues clearly activate otherwise ‘dead’ urban sites—places bound by the rules of where one does and doesn’t go as a resident of L.A., and where one does and doesn’t make something called ‘art.’”9

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978 (detail). 11 C-Prints. Dimensions variable. © Senga Nengudi. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben, New York. Photo: Quaku/Roderick Young.

Senga Nengudi, Ceremony for Freeway Fets, 1978 (detail). 11 C-Prints. Dimensions variable. © Senga Nengudi. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and Thomas Erben, New York. Photo: Quaku/Roderick Young.

In Nengudi’s ritualistic performances under the freeway, there occurred a reclaiming of space where the African body (a coming together of male and female) was at the center—the Studio Z artists created a marker for themselves because they weren’t being equally acknowledged culturally and in the world, although in 2022 many are finally getting the attention they deserve. Unhoused bodies under freeways or in tent communities reclaim similar unwanted space as their own because they have nowhere else to go. Along Selma Avenue in Hollywood, an installation of dolls named the “Voodoo tent” appeared in April 2021. Though it is unclear who the installation belonged to, the clothed dolls had brown or black fabric faces, one in a suit, another wearing a backpack—all of them resembling scarecrow figures. Palm fronds and paintings adorned the rest of the space, a bold statement among the tents pitched along Wilcox and Las Palmas. One is reminded of David Hammons’ tent installation in 2019, at Hauser & Wirth.10 Here, an unhoused artist occupied the sidewalk through their own artistic voice, which seemed to possess an African or West Indian influence, using ritual and voodoo. The tent has since disappeared from that location.11

Beginning in the late 1970s, downtown L.A. was populated by a small but thriving artist community of around 250 to 300 inhabitants, including Jon Peterson, who belonged to a group later referred to as the “Young Turks.”12 Peterson described downtown L.A. as possessing two countercultures then—the growing art scene and the unhoused. Being so closely integrated with one another, he produced a series of sculptures as a result, calling them Bum Shelters:13

Part of the idea of the piece was that this object could function as an intermediary between the different levels of society all the way from the art patron types—who are supposedly at the top of our society—[…] down to the way the unhoused observe the piece—they actually use the piece. […] And then the artist, I guess, is somewhere in between, and maybe actually goes from one level to the other because a lot of artists are pretty destitute. And yet at the same time, they might get invited to a party at the Grinstein’s and the next day they’re down there having a beer. […] So the idea was that the object can transcend social barriers, and really travel in the hierarchy of society.14

Peterson found that over time the sculptures, shaped like abstract tents and tubes and other forms, became functional as shelter for the unhoused. He placed them in a lot across from his studio in Skid Row and observed that they were used much more than he initially imagined. Peterson and his peers found an opportunity during the final part of Bunker Hill’s razing—climaxing in the early ’80s—and the rebuilding of downtown, when living in disused former manufacturing lofts afforded artists vast room to work, but often no basics such as hot water. It was a compromise that allowed the environment to become part of the art, the “psychological tension” resulting in strong, at times uncomfortable pieces.15Peterson later remarked on the apparent decline of downtown as a hub for artists, signaled by Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibition’s (LACE) move to Hollywood: “When LACE says it is moving […] because its Industrial Street ‘hood has gotten too dangerous, downtown artists know better. LACE has gotten scared. But of what? […] What those artists discovered was a neighborhood, one unique to L.A. In their enclave between the city on the west, Chinatown on the north, Boyle Heights on the east, and Vernon to the south, they found a working-class community that is multiculturalism personified.”16

In the 1981 LACE exhibition Site Projects: Downtown L.A., public sculptures by Anna Bresnick, Anthony Stephenson, and Andrew Chambers, as well as Jon Peterson’s Bunker Hill Shelter, were installed in the surroundings that reflected their origin.17 Chambers’ work was comprised of several large-scale triangular steel tents—some featuring compartments for belongings—and placed under a bridge with downtown’s skyline and Union Bank in the background. Bresnick’s architectural sculptures, Scherzo, were located at Alameda between First and Second Street. Stephenson’s Dreamstand (A Podium and Derelict’s Retreat), a wooden staircase leading to a platform, was situated directly opposite City Hall. Stephenson described the project: “On the last day of its exhibit, packing my guitar case, I took the bus downtown. Taking out the axe I had packed when I got there, I proceeded to demolish the project. As I was doing this, one of the street people walked up to me and said: ‘I hope that you realize that you are destroying somebody’s home.’”18Peterson’s shelters were set in Bunker Hill, between 1st and 4th, Hill and Figueroa.

Andrew Chambers, Art comes only from Art, Site Projects: Downtown L.A., 1981. Courtesy of LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions).

Anthony Stephenson, “Dreamstand,” Site Projects: Downtown L.A., 1981. Courtesy of LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions).

The artist-run LACE, based on Broadway in 1978, after which it moved to a space on Industrial Street in 1986,19 proved to be instrumental in the L.A. art world—particularly for video and performance art—and encouraged self-empowerment in a non-hierarchical way (its original building was acquired collectively by 13 artists with no institutional funding).20 “Formative in gathering audiences and creating a community for a number of artists,” exhibitions included ASCO, Kathy Acker, Chris Burden, Simone Forti, Mike Kelley, Suzanne Lacy, Paul McCarthy, Ana Mendieta, Branda Miller, and Barbara T. Smith, to name a few.21 LACE also housed a bookstore focused on art theory, and engaged in community-based activist art.

Joy Silverman—LACE’s former Director from 1983 to 1989—recounted working closely with the unhoused downtown because of LACE’s proximity to Skid Row and the fact that many of its inhabitants were also artists. Together with collector Stanley Grinstein, they consulted with Skid Row providers and the local unhoused community to set up a monthly account at an art supply store nearby. This meant unhoused artists and writers could get pads, paper, pencils, and other materials free of charge. Later on, these art supplies were given out at LACE itself. LACE exhibitions such as the Cotton Exchange Show, which Silverman organized and curated in 1984, featured unhoused artists as well.22

The Cotton Exchange Show,23 attended by roughly 3,000 visitors, brought together “local businesses, community redevelopment agencies, [unhoused] people, service providers on Skid Row, downtown artists and artists from throughout the city.”24 It was a radical and raw experiment, integrating “Westside art patrons” and “downtown grunge.” Silverman explains: “I wanted to bring some sense of community to an area that found it difficult to make community. […] It was about bringing together a community in a variety of different ways […]”25 Artists against Homelessness and the Homeless Writers Coalition, both non-profit organizations, were formed and met regularly at LACE, which also offered paid work to those living along the railroad tracks nearby, in turn furthering communication.

Joy Silverman at The Cotton Exchange Show, 1984. Courtesy of L.A. Public Library, L.A. Herald Examiner Photo Collection.

In an effort to clear Skid Row when the Pope visited Los Angeles in 1984, city officials decided that the houseless population should be hidden temporarily, and for 24 hours cordoned off the unhoused, including families with children, behind barbed wire by the L.A. River along Santa Fe Avenue. Silverman recalled the experience in an interview:

When we saw what was happening we tried to feed them and supplied food. At some point in the middle of that night, at about 4 a.m., the fence was opened up and they were let out. But they were totally alienated, especially the children, and just roaming the streets because their homes on Skid Row had been taken away, and now they had nowhere to return to. We learned that it was more beneficial to ask the [unhoused] children’s parents what they needed, instead of giving the children food or supplies, and formed great relationships that way.26

Some time earlier, in 1983, video artist Branda Miller shot L.A. Nickel while living in a loft in the area then called “The Nickel,” on 5th Street. Describing the area, Miller stated: “On the nickel was the lowest you could go. If you went on the nickel you could not fall lower.”27 Recorded entirely from her window, the film captures the harsh juxtaposition of artists living in Skid Row amidst raw violence, extreme poverty, crime, and drug addiction. With an emphasis on surveillance, collaborators from the video art community that came to shoot footage with her included Mike Kelley and the Yonemoto brothers.28 Miller’s apartment was located above the Hard Rock Cafe, and as Miller describes, was then a “hardcore” skid row bar, “one of the most raw-edge, intense, off-the grid-places.”29 It was bought out by the Hard Rock Cafe restaurant chain a short time later, forcing the closure of the original bar, in operation since the 1930s.

New York-based Polish artist Krzystof Wodiczko’s piece Homeless Vehicle Project (1988-89) followed the example of Bum Shelters by drawing attention to New York’s unhoused population through an object (a shopping cart-like vehicle) “designed not as a solution but to expose ‘a situation that should not exist in a civilized world.'”30 The vehicle featured a space for sleeping, a wash basin, and room for personal items.31 Seemingly practical, it was a political apparatus implemented by Wodiczko to convey a message of societal failure, precisely what Peterson had anticipated in L.A. a few years prior. In his in-depth essay on Homeless Vehicle from 1993, Dick Hebdige likens Wodiczko’s intent to the violent destruction of cities:

[…] bandages, wheelchairs, and derelict buildings. […] the homeless are revealed to be less the victims of their own inadequacies than of that linked process of economic and social transformation which Marshall Berman has dubbed “urbicide”—a process whereby speculative property development, the suspension of planning controls, redlining, blockbusting, gentrification, soaring rents, the casualization and deskilling of manual labor, and the drastic reduction of welfare and public housing programs actively conspire to produce homelessness.”32

Though New York may once have been its contender, the houselessness crisis is today definitively centered in Los Angeles. Marxist philosopher Marshall Berman used the term “urbicide” to describe “the murder of a city.”33 Berman’s explanation of urbicide uses the example of the South Bronx, which in the 1970s resembled a war zone with burned out buildings. According to Berman, it was in the 1950s that the destruction of working-class immigrant neighborhoods, and the displacement of their inhabitants in large American cities, began. In the case of the South Bronx, it was to make way for the Cross Bronx Expressway, and in downtown L.A.’s case, to clear an entire neighborhood—Bunker Hill—for the new financial center of Los Angeles.

Last days of Melrose Hotel on Bunker Hill at 130 South Grand Avenue between 1st and 2nd St., Los Angeles, 1957. Palmer Conner Collection of Color Slides of Los Angeles, 1950-1970. Courtesy of the Huntington Digital Library.

Bunker Hill became a working-class neighborhood in the post-war period, documented beautifully in Kent Mackenzie’s films Bunker Hill (1956) and The Exiles (1961).34 In Mackenzie’s first film, the Hill’s “single room occupancy” hotels are home to a thriving, low-income pensioner’s community. Although some of the rooming houses were deemed “unlivable,” landmarks such as the Hotel Melrose and The Montana Café look vibrant and populated here. As the city aimed to develop the area in the name of progress, its pensioners, Latinx, and Native American residents were displaced.35

In The History of Forgetting, Norman M. Klein argues that Bunker Hill became “the emblem of urban blight in Los Angeles, the primary target for redevelopment downtown from the late twenties on.”36 He further identifies “blight” as the word used to characterize Bunker Hill in the decades before its renewal and the image projected by city officials and developers to push for the Hill’s demolition and leveling: “In planning jargon, ‘blight’ was defined as the first step toward slum, or terminal decay.”37 In any case, residents were left without a home, and a community lost, while historic Victorian architecture was eradicated from the cityscape.38

Shoot from Melrose Avenue, Ed Ruscha, 1975. Roll 3: Westmoreland headed east to end; end headed west to Commonwealth: Image 0068. Part of the Streets of Los Angeles Archive, The Getty Research Institute. © Ed Ruscha

“In the City of Los Angeles There Used To Be Vacant Lots” reads Ed Ruscha’s billboard-style hand-painted sign from 2006. A photographic theme he continued through five decades, his Streets of Los Angeles series began in the late 1960s. Here he documents empty lots in and around L.A.—black and white images of dusty, vacant land illuminated by the bright California sun. In Melrose Avenue, Westmoreland headed east… (1975), overgrown land on Melrose Avenue in Silver Lake bears a ‘for sale’ sign. Santa Monica Boulevard, Sweetzer headed west… (1974) shows emptiness where the Pacific Design Center opened just a year later, in 1975, on the 14-acre block of a former Pacific Electric railway facility. Old railroad tracks are visible in the foreground, a far cry from the retail experience that the boulevard became. Knowing that most of these gaps have today been filled, the images conjure the sense of possibility that the city once possessed.

As Los Angeles has changed dramatically over the last 40 years and continues to do so, it is important to examine how its landscape influences its occupants in relation to creativity and community. When artist Christo was asked about choosing California as the location for two of his environmental works,39 he replied that it was the “horizontal use of the land” that inspired him, as well as the “very complex relation of urban, suburban, and rural life.”40In focusing on the legacy of a particular group of L.A. artists working downtown in the 1970s and ’80s, it becomes clear that displacement, real estate value, houselessness, and the city’s entrenched social problematic has had a profound effect on their work. Moreover, it seems that these artists considered their unhoused neighbors as part of life and the environment in Los Angeles, not only acknowledging but also including them as a given component within their art making.