Uncovering the Legacy of María Sodi de Ramos Martínez

by Rachel Heidenry

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, printed by María Sodi de Ramos Martínez, Vendedoras de Flores (Flower Vendors), 1947. Serigraph. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of Charles A. Storke, 1994.57.23. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

“My father and mother were devoted to each other… Fortunately for the family, my parents tended to complement one another. Thus, father had no interest in nor aptitude for business matters. But mother was able to handle this task with competence.” – María Martínez Bolster1

“In fact, the person who really taught me serigraphy is Mrs. Martínez.” – Corita Kent, 19762

Alfredo Ramos Martínez (1871-1946) was a pivotal figure in Mexican Modernism. Developing a signature style that blended influences ranging from the European avant-garde to Mesoamerican sculpture, he created canvasses depicting indigenous traditions, native Mexican flora, and religious icons painted in striking hues of umber and sienna accented by bold highlights of color. But while Ramos Martínez has a definite place in art history, his wife, María Sodi de Ramos Martínez — a talented printmaker — remains largely unknown. In the 1940s, following her husband’s death, María mastered the art of serigraphy in order to maintain the visibility of Alfredo’s work. Not only is María’s influence significant to understanding his legacy, it plays an integral role in the history of printmaking in Southern California.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez with his wife, María Sodi de Ramos Martínez, and daughter, María. ©The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

In 1928, when Alfredo married forty-year-old María de Sodi Romero of Oaxaca, he was already an esteemed professor and prominent figure in Mexico. The following year, when their newborn daughter María was diagnosed with a debilitating bone disease, the family relocated from Mexico City to Southern California, seeking medical treatment and a more beneficial climate. In Los Angeles, Alfredo began receiving exhibition opportunities and mural commissions, creating a strong body of work that brilliantly captured his recollections of Mexico. His monumental paintings and layered, tactile drawings on newspaper combining watercolor, Conté crayon, and tempera soon became popular among the Hollywood elite, including screenwriter Jo Swerling and costume designer, Edith Head.

María was always a fierce protector and champion of Alfredo’s work. In 1934, Alfredo accepted an important mural commission at the Santa Barbara Cemetery Chapel — a structure designed by architect George Washington Smith. A devout Catholic, Alfredo would often pray in the chapel for extended periods of time before beginning to paint. María was known to stand guard outside, making sure no one interrupted him. After his death in 1946,3 she made it her mission to uphold his legacy: she co-founded the Martínez Foundation and wrote and published the story of his life.4Most significantly, however, María learned the detailed process of serigraphy in order to produce commercial prints of Alfredo’s works and provide an income for herself and their teenage daughter. Serigraphy — also known as silkscreen printing — had been traditionally used in commercial and industrial projects; and during the 1940s, it was still a relatively new form for artistic production.

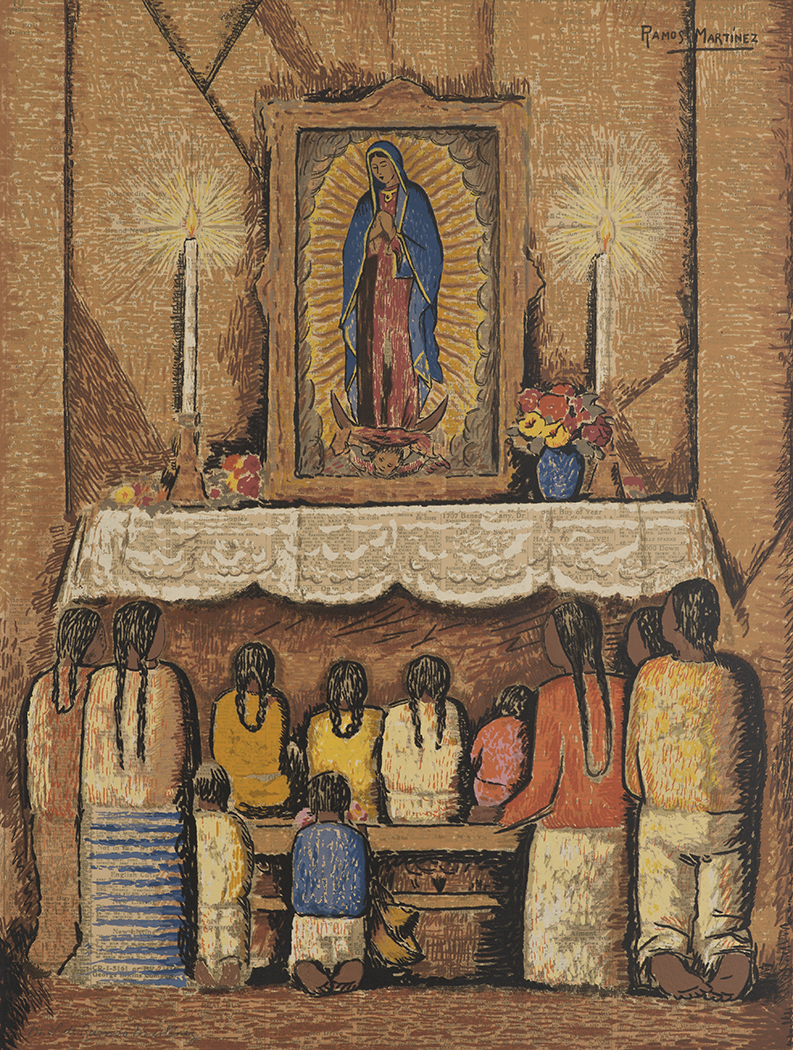

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, printed by María Sodi de Ramos Martínez, Veneración (Veneration), 1949. Serigraph. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. W.W. Seymor, 1950.13. ©The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

American painter Guy Maccoy is credited as the first artist to employ the serigraphic process for limited edition artist prints; Maccoy, his wife (artist Geno Pettit), and the newly formed Western Serigraph Society introduced serigraphy to Los Angeles. As art historian Mary Goodwin has pointed out, it was Maccoy who taught María the serigraphic process.5 In 1947, María set up a print studio in her Hollywood garage and created her first series of serigraphs with two hundred editions.6 Over a five year period, she created seven series of Alfredo’s work; the prints sold for as little as thirty-five dollars and were often made available alongside memorial exhibitions.7María’s remarkable handmade renderings capture Alfredo’s original vision and draftsmanship. Laboriously mirroring his range of colors, she was able to echo his varied textures — strict black outlines and rhythmic hash strokes – and left no detail unnoticed.

In a 1975 essay, art historian George Raphael Small admirably commends María’s serigraphs:

In Martínez’s work the stark simplicity of the forms masks the complexity of the color. His widow learned this first-hand when she undertook to reproduce the prints of his studies by silkscreen (although she had never previously done any art work). Mrs. Martínez did astonishing and inspired work which somehow made up for her lack of background, training herself as she went along, incredible as it seems. She reports that she used as many as sixty-four screens for one study, thirty-eight for another.8

The complexity of her endeavor is genuinely profound: not only did María master a complex printmaking technique, she also carefully captured and preserved the intention behind her husband’s work — his ardent celebration of Mexico’s people and culture. In the few historical references made to María’s work, her serigraphs are acknowledged as “astonishingly true.” The “remarkable likeness” that she was able to achieve is, in fact, so skillful that her prints have often been mistaken for original Alfredo Ramos Martínez drawings. And while María made sure that Alfredo’s underscored signature was always legibly reproduced — these were, after all, reproductions — she did sign her name in pencil in the lower left corner of the prints, a small recognition of her own artistry.9

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Mujeres con Flores (Women with Flowers), ca. 1946. Tempera and Conté crayon on newsprint. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of the P.D. McMillan Land Company, 1963.32.1 © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

Alfredo Ramos Martínez, Los Amantes (The Lovers), ca. 1930. Watercolor and gouache on paper. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Gift of the P.D. McMillan Land Company, 1963.28. © The Alfredo Ramos Martínez Research Project, reproduced by permission.

Attentively working to secure her husband’s legacy, María unexpectedly left her own mark on the Southern California printmaking community. In 1951, María taught Corita Kent the basic techniques of serigraphy.10As a member of a progressive religious community and teacher in Immaculate Heart College’s legendary art program, Corita had been struggling to learn serigraphy on her own when a student suggested she meet “Mrs. Martínez.” Corita later recalled, “So she came over and in an afternoon just told me all she knew. She showed me some things, and that was really all you needed to know. It’s a very simple process.”11That very simple process empowered Corita’s unmistakable art practice. Along with the Pop Art artists of the 1960s, Corita’s bold and colorful prints incorporating advertising images, political slogans, poetry, and photographs transformed silkscreening from “a sign painter’s medium” into a popular art form. As a teacher dedicated to democratic forms of printmaking, Corita prioritized silkscreening in her classroom. Among her students was Sister Karen Bocallero,12who went on to co-found Self-Help Graphics — the influential organization that brought printmaking to the Chicano/a and Latinx communities in East Los Angeles and helped launch the careers of countless artists and activists.

It is significant that such a vital and ever-expanding history can be traced to María Sodi de Ramos Martínez creating prints in her Hollywood garage. This largely overlooked history reveals deeper connections between Mexican Modernism and Chicano/a Art and the influential contributions made by women to the history of printmaking in Southern California. Although it has been thirty-five years since María’s death, so much about her life and work, as well as Alfredo’s, remains unexamined. Nevertheless, what is evident is their remarkable resilience, the indisputable bond they shared, and their profound sense of artistic innovation. In the end, by promoting and preserving Alfredo’s legacy, María became an artist herself.