When The Lights Go Out: Kaucyila Brooke on the Disappearance of Lesbian Bars

by Lorelei Esquivel

Kaucyila Brooke, The Oxwood Inn, 2006. Courtesy of the artist.

Kaucyila Brooke is an artist based in Los Angeles, California. Brooke’s multidisciplinary practices often address the politics of cultural production and sexual representation. Her projects are typically based on archival research and focus on the photographic genres of portraiture, still life, documentary reportage, and landscape. She has been a faculty member of the Program in Photography and Media at CalArts since 1992.

In The Boy Mechanic (1996–ongoing), Brooke documents a social history of lesbian bars by photographing their present and former locations in cities such as San Diego, Cologne, San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles. Brooke completed The Boy Mechanic/San Diego in 2004, The Boy Mechanic/Cologne in 2006 and began working on The Boy Mechanic/Los Angeles in 2005. Each city’s characteristics influence both the direction and methodology of her research as well as the types of art objects she produces, yielding intimate psychogeographies that trace the ties between sexuality, sexual identity, memory, and the mutability of the social spaces that allow these dimensions to exist. Brooke’s photographs, videos, and maps of The Boy Mechanic document and give authority to narratives of lesbian bar life, so often anonymous or subdued, yet ever-changing.

East of Borneo visits Brooke to discuss this project at her studio. It is 1 p.m. on a summer afternoon in Tujunga, California.

Can you describe The Boy Mechanic and how it came about?

It was the middle of the ’90s. I went to San Francisco and Amelia’s had just closed. It was the last lesbian bar there. I was shocked. San Francisco had always been the biggest lesbian town on the West Coast. The community was concentrated in the Mission, and it was amazing to go there because you could recognize dykes on the street and cruise them. Lesbian culture felt very alive.

The anecdotal reasons that people gave [for Amelia’s closing] were that a lot of women were already coupled up and had houses. They invited friends over for dinner and didn’t need to go out to the bars anymore to find a safe place; they were ensconced in their bourgeois domestic lives. I wondered if that was really the goal of queer liberation, to settle down and have private lives instead of public lives. That trend really worried me.

Then I thought if lesbian bars are something that will just disappear in time, it’s important to make an archive of where they are or were, and to meet people who frequented them who could tell their stories. I was invited to participate in the exhibition “Re: public/Listening to San Diego” at the Museum of Photographic Arts at The San Diego Museum of Art in 1996. They invited people to do things that were counter to the Republican agenda because the Republican Party Convention was happening that same year in San Diego. They were being a little bit provocative….

I started working on the project with that institutional support. I had a research assistant and funding to stay there while I collected interviews. I began by making a video: I made 30 different one-hour interviews and documented seven former lesbian bar locations and two extant clubs. Later, I returned to San Diego to prepare for an exhibition of The Boy Mechanic at the Stadthaus in Ulm, Germany. I made additional large format photographs of the sites and presented them in Ulm along with the video. That’s when I started expanding the project into a photographic archive.

Kaucyila Brooke, 4888-4878 Lankershim Boulevard (formerly Club 22 and The Big Horn), North Hollywood, California, 2005. Courtesy of the artist.

What interested you about these kinds of lesbian spaces?

I was thinking about gender and space and gendered architecture. In particular, I was drawn to preexisting vernacular architecture that had been re-purposed for lesbian bars. Lesbian bars were often in spaces seemingly devoid of architectural beauty or historical importance. I made these meticulously composed, large-format and large-scale photographs of lesbian bars and the former sites of lesbian bars to elevate them to a status of monumentality, presenting them as edifices of profound historical significance, akin to revered governmental buildings, architectural masterpieces, or the preserved homes of literary luminaries. Through this visual treatment, I want these once-overlooked spaces to be recontextualized as vital landmarks, demanding the same reverence afforded to traditionally recognized historical sites.

Lesbian bars didn’t announce themselves to the street, unlike gay bars. They usually had discreet names. That had to do with safety and the economics of lesbians’ buying power, which was not as high as gay men’s. Lesbians never had an architect design a bar for them. I’m sure that’s changed now, but at the time, it was always a space that was re-adapted from some other use. This idea of adaptation—and what you must know in a practical manner in order to achieve it—was intriguing to me. That’s why I ended up calling the series The Boy Mechanic.

The Boy Mechanic was originally a series of books published by Popular Mechanics, a do-it-yourself kind of magazine that started at the turn of the twentieth century. Its ethos was part of a thrift economy and not a “borrow-in-excess” economy. That was fascinating to me—if you aren’t just inventing new products all the time, but instead re-inhabiting spaces then you must be able to figure out how to do that. Your mechanical know-how has to be in play. Lesbian gender identity was always in question. Lesbians were perceived to be kind of boyish, so there was this sort of association with boyish know-how.

There are four volumes of the original The Boy Mechanic, and each one of them had subheads like “1001 Things That a Boy Can Build.” That describes to me exactly how women were left out of this mechanical culture, as if they couldn’t build things themselves. On the one hand, in school, they didn’t take [industrial] shop courses, they took home economics. On the other hand, within lesbian culture, everybody had to do everything for themselves. We weren’t relying on men.

If your sexual desire is organized around pheromones and how you respond to somebody, then a bar is a good place to explore that. It differs significantly from online shopping, where individuals advertise their attributes and engage in flirting through messaging. You never get that turn of the head, or the way the jeans fit, or how somebody moves on the dance floor. You don’t get the sparkle in their eye. It’s riskier in person. And that’s exciting.

How did The Boy Mechanic change when you brought it to Los Angeles?

The second city for the project was Los Angeles, which I started in 2005 when I received the City of Los Angeles (COLA) grant. That grant included an exhibition at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Art Park.

Los Angeles posed special access problems. I wanted to take lesbian social life within urban vernacular architecture and say, “These are the places people actually go. These are the places where women went and had significant experiences in their life.” That was difficult to do in Los Angeles. To a certain local population these bars would have been monumental to their personal development and social life, but they were also clandestine spaces visited at night.

I was able to find names and addresses and talk to people, but when I tried to make large format photographs, I would end up on these streets at the wrong time of day with my big camera, too far away. The streets were so busy and there were always cars parked in front of the facades. It just became impossible to make it around the city and document all of the facades.1

Instead, I documented them with my digital camera. I assumed I would go back some day, take my time, and use the 4 x 5 [camera]. I had newly acquired a Nikon digital camera and was experimenting with it. I didn’t take digital photographs seriously at the time; I was using the digital images as notes so I could strategically go back and photograph the bars in large format. But this kind of circulating, moving around the town is what made me think about making a video that would go along with the piece.

Kaucyila Brooke with 4 x 5 view camera photographing an empty lot on Lankershim Ave., North Hollywood, former site of The Big Horn and Club 22, 2005. Photo by Christy Williams.

In the video, I cruised past all the facades during the day and sort of slowed down in a dérive.2In Los Angeles, a dérive would not be by foot at night, but during the day in multiple lanes of traffic with people being annoyed at you. I was driving my SUV which had a moonroof, and my assistant, Christy Williams, was standing in the middle hanging out of it, shooting these facades as we drove by. We didn’t have movie cranes, so that made us really obvious to the people we were driving by in Los Angeles. We had a lot of reactions from people on the street, mostly from men who flipped us off or waved at us. One guy even mooned us. That encapsulated my experience of Los Angeles.3

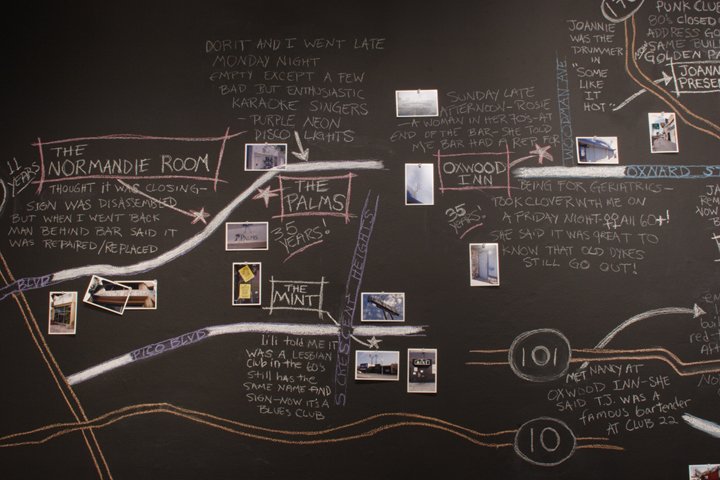

The map I made for the Los Angeles project was a solution to the scale of L.A. and a reflection of the difficulty in making the kinds of photographs I wanted to take. On the map, I drew a North Hollywood section, a West Hollywood section, and a Boyle Heights section. Of course, it doesn’t cover the entire territory; I focused on specific neighborhoods. Then I wrote in chalk and used the digital pictures to locate bar spots on the map (this was before Google Maps). At this point, I was printing maps out from MapQuest and using my Thomas Guide to locate these places. Next to the photographs, I would write down the anecdotal information I gathered from the people I met who could tell me about each bar. I wrote in chalk so it would be didactic, like in a classroom. I wanted to re-inscribe the information rather than allowing it to disappear, but, of course, it’s chalk, it risks being erased.4

Memories can be fuzzy. Memories can be erased. There’s a kind of fragility to these spaces and the memories they create.

How did visitors react to the exhibition of The Boy Mechanic at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery?

Barnsdall has a public education component to their mission. The person who was in charge of public education spoke to me about how they were going to conduct tours of the show. They had student groups visiting all the time, and she said many of the neighbors were quite conservative Christians. She decided docents would introduce my project as “Women’s Social Spaces.”

Of course, I argued with her about that—the whole point of the project is to resist the erasure of these spaces! They are bars, which are by definition adult spaces. Bars are not squeaky-clean in the American imagination, they’re seen as a little bit deviant or underground, and have been since at least prohibition. They are also historically important social spaces for political organizing in this country. Labor unions and revolutions have been organized in bars. The fact that anybody could walk into any particular bar is important for all kinds of community building. The gallery educator insisted that if they had to call it lesbian bars, they would close off my portion of the show to students. There was nothing I could do in the end. I just kept saying, “You might have children who have lesbian parents, or who are struggling to articulate their own personal identity.” This was in 2005, not the Dark Ages. There were known lesbian public figures at this point. There’s a kind of political discomfort around acknowledging words that speak specifically to lesbian desire and not to words that speak more generally to queerness. “Queer” is an important term, as is “dyke.”

Kaucyila Brooke, Los Angeles Map, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, Barnsdall Art Park, Los Angeles, 2005

Installation view, The Boy Mechanic/Los Angeles, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Art Park, 2005. Photo by Joshua White.

Where else has The Boy Mechanic been exhibited?

I showed The Boy Mechanic/Los Angeles in other exhibitions where I also brought together several cities. This is an ongoing project, and like any archive, it’s always finished and, paradoxically, always unfinished. The L.A. map keeps changing as do the maps I make for each iteration. Bars close, or I’ll learn something new about them and include it. The last time I made the map was in 2019 for the “Queer California: Untold Stories” exhibition at the Oakland Art Museum. By then, none of the bars on the map previously were still open.

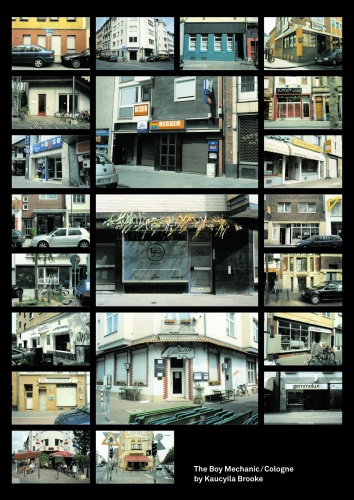

In Leipzig, Germany I showed The Boy Mechanic/Los Angeles and The Boy Mechanic/San Diego. Later in Cologne I was commissioned to complete a new series for The Boy Mechanic. I adapted my approach in Cologne because my time was limited. I worked with a medium format camera as I interviewed women and gathered anecdotal information. I presented the project in the form of a two-sided poster, with photographs on one and anecdotal information on the other. This yielded a simple way to respect the interiority and social exchanges within these places as distinct from their public facades. Facades don’t reveal much. With lesbian bars, you had to know where it was. You couldn’t just pass by on the street and say, “Oh look, a lesbian bar.”

What differences did you notice between the project’s different cities?

Most of the documentation has taken place in California: San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Oakland. Cologne is the only European city so far. But even then, the differences in what things look like are revelatory. This project is in a sense about each city’s architectural characteristics. In San Diego, you have this big blue sky and separate buildings. In Los Angeles, there are much wider streets with all the facades connecting. Cologne is a post-WWII vertical city, so it looks different from San Diego and Los Angeles. San Francisco is also a vertical city but still retains many Victorian facades.

Another thing that I discovered was that San Diego—at The Flame in particular—had a lot of women from the military or navy. It was a big military town. When I started working there in 1996, Clinton’s infamous “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was still in place, so it was unethical for me to photograph inside of the bars during working hours. I didn’t want to out anyone who didn’t want to be outed. I was only able to film inside the bar during the day when it was closed.

When I got to Cologne, two things occurred that reflected a real shift. Earlier I said that lesbian bars were hard to identify from their facades, but in Cologne, there was a bar with a brass plaque on the outside–an actual plaque that said it was the home of the first lesbian dancing group that was part of the annual carnival celebration. There was another bar near the university in Cologne called Besser Bar, which translates to Better Bar. They had a website with tons of pictures of people having a good time on the inside, not worried that anyone was going to see them in a lesbian bar. So the separation between the facade and the inside started to change significantly between 1996 and 2007 when I worked on the archive in Cologne. For all the things that haven’t changed, some things have changed a lot.

What has been your favorite city to work on?

In some ways, Cologne. It was such an open city. I’d photograph a bar with my camera on a tripod and the bar owner would come out and ask what I was doing. I’d explain the project. The bar might no longer be a lesbian bar, but the owner would say, “Oh yes, this was a very popular bar,” and invite me in. It was very friendly; there was no worry about the history of these places. They relished that history, and I really enjoyed that.

I also enjoyed the fact that the women I interviewed were very candid about the splits in their community. They said the athletic women were offended by the academic women because they were smelly and had hairy legs. The feminist women talked about how they didn’t think the jocks were intellectual enough. One of the women I met said she often “crossed the line” and went to the sports bar and had an affair with one of the women there. They happily acknowledged that they too had to break through their own stereotypes. Cologne was so much more condensed for me. I was only there for ten days, working intensely. The funding I received from the Museum Ludwig in Cologne allowed me to produce the poster, and I loved making it. I was lucky to work with the curator, Frank Wagner, who was very influential in Germany at the time, and with Kasper König, the director of the museum. It was such a relief to work on the project in a city not ashamed of all of its histories, especially after my experience making and showing the project in my hometown of Los Angeles.

Kaucyila Brooke, The Boy Mechanic/Cologne, 2006. Two-sided offset lithograph poster, 33 in x 47 in. Courtesy of the artist.

How did it feel to see lesbian bars disappearing?

I worry that the randomness of the bar encounter is going to disappear. I see this also with younger lesbians. Once we moved into the digital sphere, younger women who I knew texted each other about which bar to show up at, and they would all go to that bar that night. It is unfortunate because there was no mixing of communities. Suddenly, being queer seemed private again, and this time, at least in part, by our own choice. What I miss about being at a random lesbian bar, open any night of the week, is that I might meet somebody completely outside my circle. I might have a conversation with somebody I might not agree with, or who might act in a way I am not quite sure about. I found the experience expansive, and importantly, tolerant and transparent.

Also, bars were important for recognizing trends—what people were talking about, what other women were wearing. It’s become more acceptable to be a lesbian, and as a collective cultural space, lesbianism has just gotten more and more “norm-core.” At a certain point along that cultural shift, glossy lesbian magazines became a thing, and you could read about changing trends in them, but it wasn’t the same exchange you might have in an actual space where you bump into somebody new. I worry that in the process of becoming more accepted, there is a kind of homogenization that can happen in lesbian culture, with more of our “difficult” differences becoming increasingly erased.

What do you think of the nostalgia that is associated with these bars that have closed down?

When I started this project, there was a documentary called Last Call at Maud’s, which was about a bar called Maud’s Study in San Francisco. The film was nostalgic: it talked about how important Maud’s was for the community, that it was just a wonderful place, and that there were never any problems at all.

That bothered me. It didn’t seem like a real place. I am always looking for people with conflicting opinions, because perspectives differ depending on who is observing. For The Boy Mechanic/San Diego video, I interviewed a group of young Latina women who said that white people were always taking over bar tables or pool tables. Then I cut to a Filipina lesbian who had used The Flame to organize an Asian Social Support Group. She said, “I’d always sit right next to the pool table, and I would just write in my journal.” Any space like that is different every night. Nostalgia isn’t what I’m after. I don’t think it does any service to say a place like Maud’s was a utopia where everyone was happy. There are always conflicting perceptions of the social geography in community spaces. The different feelings that people have about a place are a more useful kind of archive.

Kaucyila Brooke, The Boy Mechanic/San Diego, 2002 (still). Single channel video, 21 minutes. Courtesy of the artist.

What do you want people to get out of the photographs in this project?

That lesbian bars can be in any kind of place. Most of them are not very beautiful. You rarely know what you are passing by on the street—and who or what might be behind the door. There is a vast history of different perceptions and experiences in a space over time. All the assumptions one might have can be challenged by entering mixed spaces like lesbian bars. If nostalgic representations claim universal inclusion, they inevitably suppress those who had different experiences.

In one case, in Los Angeles, I photographed an empty lot. There had been two different bars in that location before, but when I went to find the building, the lot was empty. It had been badly damaged during the 1994 Northridge earthquake, and subsequently torn down, a literal and metaphoric Los Angeles commonplace; if an address still exists, that’s something. It’s such a rapidly changing urban landscape.

Do you think the acceptability of queerness contributed to the loss of lesbian bars?

Yes, maybe that has happened. Is there less need for lesbian bars? One of the women I interviewed said it was horrible to be queer in the ’50s, and that it was really frightening for her generation. There were bar raids, people imprisoned and harassed by the police, but, on the other hand, she said, “The whole world out there was against us and then we would go into our bars and we would be family. We really would be family. We didn’t have families that accepted us so we made family with each other.” In some ways, she missed that part of being a gay woman that came with being a social outlaw. When I interviewed her in 1996 she felt everything had become so professionalized. She missed some of the ways we took care of each other when we were embattled. So maybe there’s a loss of political awareness that comes when you’re a targeted group in society.

In recent years what I’ve noticed is that not very many young women want to identify as lesbian. They want to be queer or non-binary or genderqueer. “Lesbian” seems a more specific identity than they feel comfortable with. But I don’t know if that’s changing again. It seems like it might be.

I think it is.

There was an article in the Los Angeles Times about all of the lesbian spaces that have recently opened in San Francisco. The article was talking about a renaissance of lesbian spaces.5 I thought it was interesting that it’s coming back again.

It might have something to do with the current political state of the world as well. Maybe it’s mirroring the tension of the ’60s and ’70s.

One of the reasons why lesbian spaces were so important then was because women were told they couldn’t do anything without men. The postwar years reimposed much older gender norms; women couldn’t change a tire or have a career. We couldn’t run for office. We couldn’t be doctors. We couldn’t have credit cards and get divorced or own property. Women in early America were legal non-entities, like slaves or children. By the middle of the 19th century, women could own property in her own right, but only with her husband or father’s permission.

Women had no idea who we were. We have been defined by this gender split between masculine and feminine. Thinking we could do something other than get married and have kids was a radical thought. My experience of this pressure was having to constantly defend against this narrative that all the men we knew were convinced of.

Having our own space and relationships with each other within our own community allowed us to explore the possibilities of what we could be. I think it is still necessary to have women’s conferences and women’s bars and organizations to continue figuring out where women’s power is or what we want. It is a form of resistance to carve out your own space and say, “This is our space,” and not just for one night.

Are you familiar with the contemporary lesbian bars of Los Angeles?

No. No one has yet offered me an opportunity to update The Boy Mechanic/Los Angeles for the 2020s.

As of now there is only one seven-days-a-week bar, The Ruby Fruit, in Silverlake, which is a wine bar. There is Futch, a lesbian night at El Cid also in Silverlake. Then there is Honey’s at Star Love, a queer bar in Hollywood that hosts lesbian events.

Time for me to catch up!