Your Everyday Art World: Glasgow to Los Angeles

by Lane Relyea

A version of this essay was originally published in Your Everyday Art World (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013). It is reproduced here with permission.

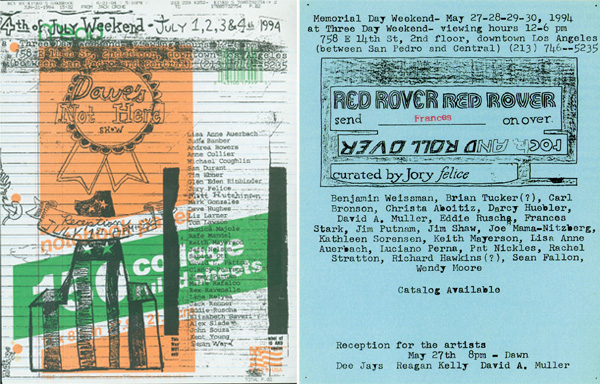

Jory Felice and Dave Muller, Three Day Weekend Flyer (Dave’s Not Here) and Three Day Weekend Flyer (Red Rover), 1994. Xerox on paper. Collection of Dave Muller. Photo: Dave Muller. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

Lane Relyea has been thinking about artists’ networks since the early 90s, when he was still living in his hometown, Los Angeles. Long before the ubiquity of the internet, he was interested in various aspects of DIY culture – from zines to pop-up galleries – and how these informal organizations influenced the art that was made and shown and discussed. In his recently published Your Everyday Art World (MIT Press), he brings together his research on three disparate scenes, in Glasgow, Koln, and Los Angeles, and shows how networked culture helped groups of young artists establish vibrant art scenes off the radar of mainstream attention until, suddenly, they were at the center of what everyone was talking about. In the course of the book Relyea teases out similarities, and draws out connections. Here we excerpt a chapter on aspects of new art being made in Los Angeles in the first years of the decade.

In the catalogue for the 1996 show “Life/Live,” a survey of ’90s art in the U.K., curator Hans Ulrich Obrist wrote that “artists’ initiatives” were one of the main “reasons for the extraordinary dynamism of the British art scene.”1 Two years later, Obrist found himself similarly weak in the knees when confronted by the scene in Los Angeles. While interviewing recent CalArts alumnus Dave Muller about his ongoing project Three Day Weekend, Obrist confided, “When I made studio visits in L.A. earlier this year I found that the dialogue between artists is stronger than in New York. It actually reminded me of the Glaswegian situation where spaces like Transmission go hand in hand with lots of other artist-run initiatives.”2

Muller generally agreed. “The issues that Three Day Weekend might bring up through its sheer existence—the nomadic, D.I.Y., temporality, situational/context, non-monumentality—I see as being topics pertinent to my immediate generation.”3 In many respects Los Angeles and Glasgow couldn’t have been more diametrically opposed. Rusting Glasgow on the one hand, trying desperately to deflect tourist money its way by selling nostalgia for its ye-olde maritime industry, versus L.A. on the other, global behemoth of such virtual industries as media and finance, with its aero-space futurism and show-biz culture and seeming lack of any past. In terms of their art scenes, though, both cities had long experienced marginalization. Los Angeles suffered under New York’s shadow much as Glasgow felt eclipsed by London’s, both deemed provinces, quirky at best, otherwise just sparse and irrelevant.

Also like Glasgow, in the mid-’80s L.A. began to invest heavily in the arts as a way to shore up its global reputation. In 1986 the Museum of Contemporary Art opened (its name changed from the originally planned Los Angeles Museum of Modern Art, thus “signifying that it would present art from an international rather than regional perspective”4), and a year later the city hosted a sprawling, big-ticket international arts festival. As with the “Capital of Culture” campaign in Glasgow, in L.A. the response was admiration from afar and disillusionment locally. “Potemkin Village,” scoffed Linda Frye Burnham in the L.A. Weekly. The city, she lamented, “touts itself as the next capital of art, but treats its artists like illegal aliens…. We adulate state-supported geniuses like Pina Bausch and Maguy Marin, whose spectacles are the product of healthy arts environments elsewhere… [while] L.A. artists are in a desperate state, fighting over scraps, without career opportunities, funds or housing.”5 But of course local artists weren’t the ones the festival’s sales pitch was aimed at.

Installation view of “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s.“ Photo by Paula Goldman. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

While Glasgow tried to reverse its reputation as depressed, violent and dark by going for a brighter, more intellectual look, L.A. tried to counter the overly sunny, “light and space” stereotype that burdened its art by demonstrating that it, too, had all the dystopian, noir characteristics of an authentic urban jungle. To that end, in 1992 the Museum of Contemporary Art opened “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the ’90s,” which applauded local artists for, as curator Paul Schimmel wrote in the catalogue, their “use of debased signs and symbols and embrace of raw subjects from everyday life.”6 Despite such brand differences, though, the goal remained the same for the two cities: getting “on the map.” Schimmel was quite explicit on this point in his catalogue essay: “L.A. does have a culture of its own … its community is different from others … ‘regional’ art need not bear the burden of provincialism.… Increasing globalization and changing economic conditions make it apparent that there will never again be singular cultural centers in the way that Paris and New York once were,” Schimmel concludes. “In fact, it is clear that there are to be many centers, with L.A. playing a prominent role in that international circuit.”7 Beyond marketing, the two cities also shared certain structural features that gave them a potential competitive advantage in the newly emerging global circuitry. Unlike other metropolises, neither L.A. or Glasgow (or London, for that matter, at least not until later) would have to host any international biennials or art fairs to generate buzz and gain international visibility. For one thing, like in Glasgow, young artists coming out of Los Angeles art schools could look to certain important members of the immediately preceding generation—Mike Kelley, for instance—who had decided to stay in town even after gaining recognition abroad. Through their teachers, students met European artists and were given opportunities to visit and exhibit overseas. Art Center in particular helped maintain constant traffic between Germany and Southern California, in the early ’90s hosting Chris Dercon, Diedrich Diederichsen, Jutta Koether, Martin Prinzhorn, Albert Oehlen and many others as visitors and teachers, most of whom needed local students to drive them around or assist with projects, etc. Especially helpful at the other end was Diederichsen, who lived in Cologne and taught at Stuttgart’s Merz Akademie. Christopher Williams, for example, while teaching a workshop in Stuttgart at Diederichsen’s request set up a show there of work by Sharon Lockhart, Frances Stark and other L.A. graduate students. Muller’s first-ever Three Day Weekend event was a response exhibition of work by Diederichsen’s German students. Only months after her graduation from Art Center, Lockhart was invited by Diederichsen to teach a workshop in Stuttgart; and with her help Muller and fellow CalArts grad Laura Owens made their first trips to Germany. And so on.

As for so many other types of operations or “actors” responding to increased globalization, no less for artists did the decisive factor become circulation over location. Flexibility came to characterize not only how this generation approached roles and contexts but location more generally. To be seen as a viable art center at a time when, in Schimmel’s words, “it is clear that there are to be many centers,” a city’s art scene didn’t overly concern itself with vertical integration, it didn’t isolate itself within an airtight aesthetic, discourse, patron base, etc. The secret to Los Angeles’s emergence as a center in the ’90s was that it succeeded at functioning less like a self-contained hierarchy and more like a hub or platform—it didn’t root itself more deeply in a local identity and economy but grew more porous and horizontally interpenetrated, more easily exchanging its art, artists and art money with other places. Young graduates looking for a place to set up shop talked about L.A.’s comparative advantages, that living there wasn’t a necessity but a preference. Liz Larner, for example, confided that “after graduating in 1985, I felt if I went to New York I would be overwhelmed with too much information. I wanted to be someplace a little quieter. I needed to have more space around me—mental, physical and artistic space. L.A. was a lot cheaper than New York.”8 No less for artists did the question of geographical location become more like a consumer choice.

Diana Thater, Up the Lintel, video installation at Bliss, Pasadena, 1992. Photo: Diana Thater. Courtesy of the artist and 1301PE, Los Angeles.

Another similarity between Glasgow and L.A. was the lack of commercial prospects. If the 1990 art market crash had dimmed the allure of New York and its galleries, it also meant that chances for freshly diplomaed L.A. artists to find accommodating galleries locally had gone from slim to none. But even before the recession hit young artists were coming up with their own exhibition venues. In 1987, three Art Center undergraduates renting a house together in Pasadena—Gayle Barkley, Jorge Pardo and Ken Riddle—decided to use their garage to hold a group show featuring work made by classmates and objects contributed by neighbors. The following year the threesome made official the house’s status as an art venue by giving it a name, Bliss (after Guy S. Bliss, the house’s Craftsman-era architect), and Pardo opened his first ever solo show there, five months before receiving his BFA. That dealer Thomas Solomon, ex-director of New York’s White Columns who moved to L.A. to run a short-lived Venice Beach branch of Manhattan’s Piezo Electric Gallery, stopped by the house to view Pardo’s work, and would later give him his first commercial-gallery show, upped the stakes considerably. Also in 1988, CalArts graduate Dennis Anderson turned heads by opening a “guerrilla gallery” with a group show featuring current and recent students from his alma mater—”not a curated show,” explained admirer Bonnie Clearwater, “nor was there an attempt to make a statement about the type of work these artists are producing.”9 Clearwater found the exhibition’s informality and diversity “surprising … since recent exhibitions of CalArts graduates”—shows like 1988’s “Skeptical Beliefs” that featured famed pictures-generation alumni like David Salle and Eric Fischl—”seemed unusually cohesive for group shows.”

Remarkably, it was during this time, with the downmarket choking off L.A.’s already emaciated ranks of white-cube commercial galleries, that serious talk arose about the city finally securing its place on the international map—or, as Clearwater declared in 1989, “that the much anticipated emergence of the city as a viable art center has become a reality.”10 And what especially drew attention were the new D.I.Y. spaces. Although here it wasn’t just artists driving the movement: besides Bliss and Dennis Anderson, and the room that artist Russell Crotty dedicated in his home for solo art exhibitions (called “The Guest Room”), gallerist Solomon opened an exhibition space in a single-car garage accessed through a back alley in the Fairfax District. Then in 1992 came a flood of impromptu spaces, including TRI, Nomadic Sites, Food House (which would eventually grow into the blue-chip ACME Gallery) and 1301 (named after the street address of proprietor Brian Butler’s apartment-cum-gallery on Franklin Avenue). The following year even powerbroker Stuart Regen arranged for Richard Prince to install work in a beat-up West Hollywood one-bedroom slated for demolition. “In contrast to the market’s contracting top is the expanding bottom,” was how the New York Times‘ Roberta Smith framed her 1992 write up of Los Angeles’s “new image”—an image featuring “no-frills … shoestring galleries … [some in] unrefurbished storefronts or private homes; others lack permanent addresses. Most concentrate on showing the young artists coming out of the area’s unusually plentiful and unusually good art schools.”11 Anticipating descriptions by Obrist and others of the game-changing impact of D.I.Y. spaces in the U.K., Smith concludes, “What’s emerging at the grass roots level may be a gallery for a small art scene, something flexible, modest and right in the living room.”

Richard Prince, First House Installation (detail), April 3 – April 30, 1993, 540 Westmount, Los Angeles. Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Richard Prince.

What had changed in Los Angeles, in other words, was the replacement of a hierarchical structure with something flexible, with a network. Off the beaten-path, often located in not commercial but residential neighborhoods and identified as neither for-profit businesses or nonprofit community-services, the new D.I.Y. spaces helped to fragment and disperse the spatial layout of the local art community, both as a part of urban geography and as a set of institutional and conceptual categories. And the city’s ability to impose a single definition on the art it produced slackened as well; having been obscured by the heavily relied on and overly well known, albeit dismissive, totalizing stereotypes of “finish fetish” and “light and space,” L.A. artists now appeared likewise more spread-out and under-categorized, known as merely individual practitioners, all the more so as they more routinely left town to travel, thus becoming more unanchored, nomadic and underdefined by place per se. L.A. artists were now seen as less a cohesive category than an informal collection, a weak rather than a strong-tied network.

Nevertheless, it was the performative nature and sociality of the network, despite its loose ties, that participants emphasized. What these younger artists seemed to be gesturing toward was a differently imagined frame or apparatus that situated and underwrote their art, that redistributed emphasis away from rigid institutional and ideological categories toward a more loose, intimate framing. Familiarity replaced the sense of revelation that had previously accompanied awareness of the complex apparatus that framed and underwrote the work of art. The idea of “unmasking” art’s institutional conditions and supports was replaced by something closer to the more recent idea of “radical transparency” (a phrase popularized by Wired‘s Clive Thompson, who explains, “Your customers are going to poke around in your business anyway, and your workers are going to blab about internal info—so why not make it work for you by turning everyone into a partner in the process and inviting them to do so?”).12 Suddenly the artworld’s operations, its institutions, exhibitions, publicity, marketing and commodification, all were treated in a nonchalant and conversational way; they were no longer made models or examples out of but rather lived and breathed on a mundane, daily basis. They became the very means of increased communication.

Many people who first saw this art, or who attended the crowded openings in people’s small living rooms and noted the sharing of resources and tasks that such endeavors entailed, regarded it all as evidence of a healthy, young community beginning to come together. And it could well have been that, but it was also a community existing fully inside, not outside, the art world. These artists were no less professionalized, perhaps only more diversely so—and thus perhaps more intensely or fully so, to the degree that a wider range of administrative and professional tasks became part of one’s overall art practice. Using one’s apartment as an exhibition site meant not having to sign a separate lease, connect a new phone line; it meant working at home, but also turning one’s home life into work, or disregarding any distinction between the two. It also didn’t affect the rent, but it did get listed on one’s CV; same with curating a show at your friend’s place—you took credit for it but it didn’t mean you suddenly stopped being an artist and switched career paths. There was less of a sense of long-term commitment, more impermanence and turnover. And this increase in flexibility, in the turnover of temporary spaces and job titles, meant there was no excuse to delay or hold back; nothing stopping one from always being visible, involved, contributing—even before graduation, one’s career was always in progress, the CV always expecting the next entry. The feeling grew that the art world as customer was always waiting, each month opening a new round of exhibitions, printing a new batch of magazines and catalogues, etc. The result was a greater need for the next job and the next space and possibly yet another title—in other words, a constant supply of readily available players and occasions for ever new temporary projects.

While a somewhat more fluid and horizontal scene might have emerged in L.A. during the ’90s, it was still very much a separate sphere of activity. Again, perhaps more so: the new spaces mostly addressed themselves to niche or insider groups, namely fellow art-school classmates. As everyone who reported on them noticed, the apartment galleries were literally hard to find—not identifiable from the street by signage, with spotty advertising and little or no administrative structure like a reliable contact number and regular hours of operation, etc. This was part of the modesty and authenticity they exuded, how they strictly eschewed any claim to broadly represent the city’s art population as a whole. Who these spaces addressed was not some abstract entity, the public or civic society in general, but specific audiences, people one knew. “The participants are your friends?” Muller was asked the year he started Three Day Weekend. “Yes,” he answered, “and friends of friends.”13