Artists at Work: Susan Silton

by Susanna Newbury

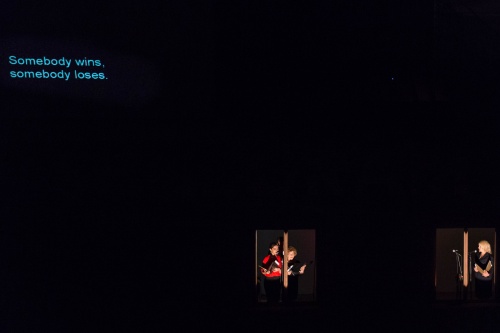

Susan Silton, A Sublime Madness in the Soul, 2015. Excerpt from video documentation. Musicians: Clinton Patterson, Alex Ward. Videographer: Alina Skrzeszewska.

Susan Silton first moved to downtown Los Angeles in the early 1980s and has been immersed in the city’s multiple worlds ever since. Her work in many ways focuses on the acts of gathering and witnessing. Be it a community of whistlers and typists, or even the observers of gum spots on the sidewalk, Silton orchestrates observation as a critical act of our time. In September 2018, Susanna Newbury sat down with the artist to discuss decades of development and gentrification in Los Angeles and pinpoint how Silton’s work frames and criticizes an active art of lyricism and its political grounding in a contracting public realm.

Susanna Newbury: I thought I’d begin by asking you about your long history here in LA. Can you tell us how your family came to Los Angeles, your connection to the city, and how things have changed for the Siltons over the decades?

Susan Silton: Sure. I’m a native of LA—an anomaly! My father was born in Vienna, Austria, and was forced out in 1938 when he was 14—either just before or after Kristallnacht in November 1938. His family came to the United States by way of Poland, to St. Louis, where they were sponsored by relatives, and then eventually moved to the west coast.

My siblings and I grew up in a modest West Los Angeles apartment building near the Mormon temple. My grandfather, who had been a tailor in Vienna and lost pretty much everything when he and the family emigrated, established a clothing manufacturing business in St. Louis with his brother. They moved here in 1946 and relocated the business to various locations downtown—first on Santee, then on Main and Jefferson, and then to 35th and Broadway. My summers as a child were spent working at the last two locations.

Advertisement for Silton Bros., 3400 South Main Street, Los Angeles. c. 1960’s, Playboy magazine.

SN: What did you do?

SS: I mainly filed, but I did some typing and other odd clerical jobs like counting buttons. One summer, there was a big perk: the budding lesbian in me developed a crush on a woman who worked there, I remember her having a tattoo on her chest. I couldn’t wait to come to work that summer.

Flash forward to not long after I graduated from UCLA in 1978, where I majored in English literature and creative writing. My Dad had been making the slow transition during this time from the clothing business to residential real estate. I’d overheard him talking about a building downtown for which he’d somehow inherited the lease but which he was having a difficult time leasing, located on 8th Street and San Julian. Manufacturing had already begun to move overseas, leaving many industrial buildings vacant at that time.

I was still at sea following graduation, trying to find myself creatively. I was writing freelance, experimenting with some other forms, and barely making ends meet, so I ended up working for my father for a brief but torturous time. And I had read somewhere about artist lofts proliferating downtown and suggested to him that he transform the unleased building into lofts. On kind of a dare, I ended up taking the project on myself—I designed and supervised construction, pre-leased the building, and lived in and managed the building from 1981-87. For a few of those years I was lucky enough to buy and co-own it.

Silton’s loft in the 1980s on 8th St and San Julian. Gorky’s Russian café was on the bottom floor of building behind tree; its unlit neon sign remains. Photo: Silton.

SN: In some ways, the geography that you’re describing sounds like a template for artist studios and urban change in the United States since the ’70s. There’s a garment district suffering the out-migration of industry and a fair amount of open real estate with raw industrial space inside, and in order to keep the buildings from falling into disrepair, someone like you—a young, enterprising person who knows people are looking for inexpensive places to live and work—suggests how these spaces might be repurposed.

SS: Yes, exactly. Downtown had experienced an earlier wave of artist migration in the 1970s even though live/work space hadn’t yet been legalized. LACE, founded by artists, had its first home in the bridal shop district on Broadway. But in 1981, the city had passed the Artist in Residence (AIR) ordinance, which allowed people like me to legally live and work in former industrial spaces, with relaxed zoning and building regulations. Many artists at that time took master leases and subdivided large buildings with the city’s blessing, just as I had done. There were also projects like the Santa Fe Arts Colony, a former garment factory converted into rent-restricted lofts in 1986, with long-term support from agencies like the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA), so city government was active to some extent in making it financially possible for more artists to be downtown.

The now hipster-populated Main Street that you see today, in the heart of the Bank District redeveloped in recent years by Tom Gilmore, had seen artists in the 80s living and working among more marginal populations as well as long established businesses which catered primarily to Spanish-speaking residents.

SN: Certainly, when I moved here in 2011, that strip of Main Street and Broadway you’re describing still seemed to be an incredible hub of immigrant activity. The old movie palaces were Seventh Day Adventist cathedrals with Spanish-language mass. There were Western Union outposts and buses that would take you to El Paso and Juarez and beyond.

What’s interesting to me is that downtown—from the late nineteenth century until the 1940s, really—was the geographic center of a Los Angeles that stretched to MacArthur Park on the west and Evergreen Cemetery to the east. But by the late ’70s, downtown itself had become geographically marginal to the vast physical plant Los Angeles developed into. It seemed to function as a thirdspace, a location where there was no natural economic or social magnet drawing people together. But in some way, that absence formed an arena for experimental social relations—for different marginalized populations to move in and create new, overlapping multinucleated communities.

SS: Yes, it was vibrant in the early 80s for all of those communities. Even though addicts and prostitutes hung out, especially in the alleys off of Main, the area was a pulsating commercial center. Being rooted in that center of commercial activity creates a strong sense of place-making as a form of culture.

The landmark Gorky’s cafe opened in 1982, a few blocks south of Skid Row. It changed ownership and closed in 1993, but the neon sign still hangs there, a relic from an area that had once been home to a vibrant community of artists living and working among other communities, not so much displacing them. Currently the area seems to be primarily discount flower vendors, including at the former café.

SN: Tell us more about Gorky’s, because when you mentioned it the previous time we met I had never heard of it.

SS: It was opened and managed by Judith Markoff, an entrepreneur and former librarian at Manual Arts High School, who’d spent quite a bit of time downtown with students and artist friends of hers. Eventually she had a vision to open a café and settled on a space a couple doors down from my studio building, which was situated among discount garment businesses and, strangely, the Los Angeles Police Protective League next door. At first Gorky’s was open just for breakfast and lunch, but then it became a 24-hour café, and the area suddenly had an active nightlife besides the Wholesale Flower Market coming alive across the street late in the evenings. It was really one of the few places in downtown Los Angeles at that time, other than Al’s Bar, Atomic Café, and Downtown LA the Café, that had a nightlife that catered to local artists.

Façade of Gorky’s Russian café. Photo: Silton.

SN: Well, it makes me wonder about your social experience of being in this location—perhaps somewhat divested of activity but slowly being repopulated, presumably by young people you had some things in common with. What did you think about being down there and how did being concentrated in one area influence you, as individuals but also as a group?

SS: I think my initial connection was somatic!—maybe a kind of bodily understanding of my father’s—and his father’s—evolving business downtown even though I was too young to really understand. And then when I lived downtown, I felt so far away (in every respect) from the landscape I’d grown up in. It was eye opening and hugely expansive. We grew up in a fairly insular and fear-based environment—neither of my parents had been college educated, neither of them went to museums or lived a life of the mind. Walking the streets of downtown and coming into daily contact with so many other Angelenos was thrilling. I didn’t really see my time downtown as being concentrated in one area—it felt as if the whole of downtown and its multiplicity was the vista.

SN: The reason I bring it up has to do with connecting your work now with your work and social experience of community then. As I’ve experienced your work, it can result in objects. It can result in a performance. It can purposefully bring participants together into a temporary exchange of ideas. It can result in political critique, but it’s always anchored in a deep analytical and intellectual parsing of the politics and importance of the relationship between words and actions. How did you get to that point?

SS: That relationship (between words and actions) has guided my entire being—it was just a question of finding the right avenues for expression. So, when I moved downtown, after a brief foray in hand painting and selling functional objects like portfolios and placemats, I found my way to a couple of graphic design classes at Art Center, and boom. Lightbulbs went off. Everything about graphic design appealed to me: the mutual dependence between text and image, how meaning is constructed and distributed, and the language of ascenders and descenders. Soon after, I lied my way into a design job at Los Angeles Theatre Center (LATC). The theater moved from Hollywood into a huge CRA-funded, four-theatre complex on Spring Street. During this time, I honed my design skills in part with the help of the Woman’s Building’s WGC (Women’s Graphic Center) in Chinatown, which did type-setting for many local businesses and designers.

In some ways, nothing could be closer to words and actions—aesthetically speaking—than theater, so it was pretty seamless to land there after college. And LATC was a true hotbed of diversity, which was super exciting; it attracted so many politically and socially engaged artists during and after my time there: Reza Abdoh, José Luis Valenzuela, Evelina Fernandez, David Henry Hwang, Mabou Mines, Luis Alfaro, to name just a few.

Even before I called myself an artist, I was driven by a fierce interest in perception and how it’s constructed. The history of graphic design is a history of recording, is a history of photography, is a history of protest. But it’s also a history of propaganda, of misinformation, of distortion. The combination of all of those realities held me then as it holds me now.

My young lesbian body became an entry point into making my own work. Early on I incorporated actual perception devices such as stereoscopic viewers and utilized some design strategies to look at and subvert perceptions about lesbians. The queer body is always present in my work, but now I’m more directly interested in bodies in relationship to one another, vis-a-vis power, vis-a-vis politics.

SN: That’s a really important point, because on the one hand—since I like dichotomies—you’re talking about a kind of ontology of gendered perception: How do I know what I think because of who I am? But on the other hand, you’re also talking about relationships, as you said, between bodies in space—

SS: Right.

SN: As soon as you develop a relational awareness of one entity to another, to a certain extent you’re talking about a public, even if it’s a public of two; you’re talking about self-perception, projection, and reception. To that idea of reception, can you think of an early example of a work that was particularly meaningful to you and also a spectacular failure? Or one that was personally meaningful to you because it generated a different course of action for later works?

SS: An early work called Stand Back and Tell Me if You Think it Looks Even was part of an exhibition called Utopian Dialogues, curated by Betty Brown at the Municipal Art Gallery in 1993. It was an installation, sculptural in nature, but it began with a conversation that I hosted at my house that included Terry Wolverton, (my romantic partner for ten years and a lifelong friend), Harry Hay, Alice Y. Hom, Ivy Bottini, Luis Alfaro, and others from the queer community. I brought folks together to discuss the relationship between lesbians and gay men in the wake of AIDS. When AIDS became a huge epidemic, lesbians rallied, as women often do, to step into care-taking roles. The crisis helped soften what had, long-term, been huge divisions between our communities.

Susan Silton, Stand Back and Tell Me If You Think It Looks Even, 1993. Wood, paint. Detail from installation as part of the exhibition, Utopian Dialogues, curated by Betty Ann Brown at the Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles.

It was the beginning of what would become a long-term investment in community. Whether or not the installation reflected that line of inquiry, the process of bringing people together to discuss our difficulties in an open-hearted way, and to talk about AIDS under Reagan, was so valuable.

On multiple levels, then, we addressed our own fears of the other, our own hopes for those relationships, our histories, and the ways in which what conspired to separate us could engage us to come together and left with an ultimate sense of hope for our communities going forward.

SN: What’s striking me as you’re talking is how this idea of the entrepôt, or crossroads, is coming up again. Gathering people for a temporally circumscribed period in a new location, you established a platform for exchanging ideas and activities meant for export—collectively wrought personal experiences that individuals hold onto and take with them. When I think about your more recent works, they also utilize these two ideas: the entrepôt as a place where individuals come, engage in an exchange, and leave; and the cultivation of a personal intimacy that is closely tied to geography.

Perhaps we could relate that, skipping a couple of years for sure, to some of the work that you did at your later studio on Anderson Street, which also eventually was tied to location.

SS: So, I moved out of the San Julian loft in the late 1980s, and years later in 2005 moved into a day studio on Anderson Street. In the first few years, it was still quite desolate, a transitional manufacturing area. It was right under the 6th Street Bridge, one of a group of iconic bridges built in the 1930s spanning the Los Angeles River.

Change in the area became noticeable a few years into my being there. Gentrification isn’t just about artists occupying “new,” inexpensive space. Film scouts began to come in on a regular basis, which signaled impending shifts. To film companies, the area came to be known as New York West because of its groovy industrial character and proximity to Downtown, and the dramatic views from under and on the bridge. The Soloist [a movie based on a Los Angeles Times article about a brilliant, homeless musician] was filmed right in front of my building in 2008. It was pretty twisted—they set-dressed it like the LA Mission from just a few blocks away, down to placing cigarette butts and trash. Not far away from Anderson, 356 Mission had opened in 2012, but within one year—2015—three galleries opened on my street! That same year, my landlord sold the building and the 6th Street Bridge was slated to be demolished because it was structurally unsound. Trendy architect Michael Maltzan was hired to rebuild the replacement. For me, it became a perfect storm.

Façade of loft building on Anderson Street that Silton worked in from 2005-2015. Photo: Alexandra Brown.

I looked through the windows of my studio one day, out towards the bridge, as I’d done countless times during the prior ten years and realized in that moment that I needed to move, and to make a piece that spoke to the current situation.

A Sublime Madness in the Soul was a mini opera staged through my windows and the windows of the adjacent empty studio. I commissioned opera singer/performance artist Juliana Snapper to devise an improvisational score for four singers and compiled a libretto from lines excerpted from films about money, power, and greed, like Wall Street, Do the Right Thing, It’s a Wonderful Life, and The Great Dictator.

The title is taken from 1930s theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, who suggested that the hunger for justice can begin to resemble a sublime madness, but that hunger, and madness, is imperative to maintaining hope.

The piece was performed twice on the night of August 22, 2015. It opened with singers in individual windows but then at times they came together in one window, as more of a chorus. Each of the windows was illuminated, and the piece was amplified from the roof of the studio building. To view it, people walked on to the bridge from either Boyle Heights or downtown until they could see the building.

Documentation from A Sublime Madness in the Soul, 2015. Photo: Alexandra Brown.

SN: Who did you expect to come to this thing? Obviously people do walk in Los Angeles, but it’s not like Manhattan—there’s not an endless crowd of passers-by. To a certain extent, you have to either put a lot of faith in someone being there to hear it, invite people, or be comfortable with no one hearing it at all.

SS: Well, of course I wanted as many people to see it as possible, but you don’t have control over attendance. I did what I could to get the word out and hit surrounding neighborhoods with fliers in addition to advertising on social media. One of the unplanned highlights for me was that a Saturday night car club cruised continuously back and forth on the bridge during the evening’s first performance. The cacophony (both musically and conceptually) could not have been more relevant, and resonant.

SN: Your work is responsive to change in a way that doesn’t necessarily seek to alter its course but to highlight the intimate politics of its occurrence. It seems as though A Sublime Madness in the Soul created a fixed point around which people could react, move, and change. The site of the bridge seems conceptually relevant as a conduit for movement, but it’s historically appropriate for this work, too, having been built in the 1930s, a decade of profound social upheaval generating mass migration and terror. The work also seems profoundly public in how it engages an anonymous audience to gather and form a temporary community around the intimacy of the encounter. As a form of public art, it might seem counterintuitive—it’s fleeting, not a physical intervention with collateral consequences for redevelopment or social displacement—but it produces personal and collective consciousness in response to stimuli. Crucially, it’s not a physical intervention with collateral consequences for redevelopment or social displacement.

SS: Intimate and public, both, yes. And less interested in activating change than in activating feelings, which, who knows, may in fact lead to change, but from within. I don’t respond well to didactic works. And I don’t respond well to work or actions that use bullying as a political strategy. What I hope for the work is to illuminate, to bear witness, and to provide some pause in terms of reflection on the complexity of a given site, or given idea, or given set of conditions.

Still from night of performance of A Sublime Madness in the Soul, August 22, 2015. Video still on 6th Street Bridge. Video still: Alina Skrzeszewska.

SN: “Bearing witness” is the perfect phrase for this work’s work, I think. Different people gather and in so doing formed a witnessing community grounded in the most elective of affinities. This idea of witnessing also has profound moral and ethical implications when we consider the social, cultural, and economic sea change underpinning your creation of A Sublime Madness in the first place.

SS: A very different kind of bearing witness and community gathering happened in a piece I made and posted on Facebook in the immediate aftermath of the Pulse nightclub mass shooting in 2016. Somewhere between a gesture of defiance and desire, I filmed myself dancing to Vicki Sue Robinson’s iconic disco tune Turn the Beat Around. I felt at the time as if it was the only thing I could do in response to what had happened. But I think it became an assertion of the queer body persisting, surviving, never giving up or giving in, the body making a dance floor anywhere, anytime, in the face of hatred and violence. It was both intimate and public, and maybe it went viral because it was simultaneously all of these things—a witnessing, a subjective experience, a space of belonging.

SN: It occurs to me that this echoes an impulse in your earlier work to explore the boundaries of self and other, mediated through the body personally experienced or received. It’s a different way of being public—thinking about the repercussions of a person or their activity beyond the boundaries of their own experience. At a very basic definition, perhaps that’s what a public is, an awareness of a multiplicity that doesn’t just reframe the individual.

Documentation from A Sublime Madness in the Soul, 2015. Photo: Alexandra Brown.

SS: Yes, in the work I danced for myself—my personal form of grieving—but I hoped it could embody many people’s grief. I find that with spectacles and casts of thousands, it’s more difficult to access feelings and content, since the content is too often the spectacle itself. I tend to focus more on intimate collectives because they’re more meaningful to me personally, and I like to construct situations that allow for others to feel.

SN: It might create a flashpoint, but as you say it’s very much grounded in the idea of establishing an intimacy, or affinity, between otherwise disinterested parties who bear witness together. As you say, it’s not didactic or even directly issue-oriented like a lot of organizing or activism is. It doesn’t advocate for a measurable, actionable outcome, meaning change. Nonetheless, both conceit and process accomplish similar work to galvanize a sense of connection, personal solidarity, even in the absence of a finite end goal.

SS: Absolutely. Which kind of leads into Quartet and how that developed.

SN: Tell us about Quartet. What was it? When did you make it?

SS: In 2016, Shamim Momin, founder of LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division) invited me to create a work as part of a series she was developing called Exchange Value—all works to be sited downtown. I’d been feeling so stressed out leading up to the Presidential election. And immediately after, I felt paralyzed, along with everyone else I knew. One night I felt drawn to listen to composer Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, probably his most well-known piece of music. Although I’d listened to it before, this time it made me weep. I hadn’t known the work’s history, but soon discovered that Messiaen was a French soldier when he was captured by the Germans in 1940, and imprisoned as a POW at Stalag VIII A in Görlitz, Germany. He wrote Quartet primarily while incarcerated, and it premiered in the camp in 1941, played by Messiaen and three other musicians who were also prisoners.

Site location, interior, for Quartet for the End of Time, 2017. Photo: Chris Wormald.

I felt an urgency to present the work, and the piece developed quickly from there. I wanted to stage it in a non-traditional setting—so often, concert halls neutralize a classical work’s historical context. We found the perfect site, a cavernous brick building for sale not far from the arts district downtown. It was fully enclosed and in a sense oppressive, kind of like an old barracks. From the beginning I’d envisioned an all-female quartet and four female dancers. Vicki Ray, one of LA’s most highly regarded pianists, was immediately on board to organize the quartet. And I invited choreographer Flora Wiegmann to create a very spare score and she, too, was immediately on board. I imagined the dancers functioning like spirits or daemons of the musicians, or possibly witnesses.

SN: A couple of things jump out of me, first of which is you’re describing a work that has a number of unknown factors including the audience. But you’re also playing with a central element in performance, and particularly with music or scores—that as performed responses to the sparest of notation, they’re newly original with every execution. Furthermore, any piece of music that is performed, as we know from Cage and others, is a sonic environment that’s the product of a witnessing audience, the ambient environment, historical conditions of building, and so on and so forth.

I find that very interesting and perhaps another way of thinking about how all of your work has been attentive to histories, whether mobile histories of the movement of people, or histories of how a body is received or performs in space for political, or social, or private ends, or even thinking about location as a silent frame for your work no matter what. I mean all those things seem to come to rest in your staging of this perhaps cathartic set of two nights in, what, 2017 at this point?

SS: Yes, June 2017.

SN: Because I’m not particularly familiar with the music, can you describe some of it? Because music of course is this really weird thing where it’s so abstract that anyone can cathect to it and bring out memories or ideas, but that comes from the intimate experience of actually listening.

SS: Quartet registers every emotion—the eight movements are filled with incredulity, anger, aching beauty, and a blend of resignation and quiet acceptance. If for no other reason, I wanted to provide a communal place for people to feel this range of emotions in such a despairing political moment. Across Quartet’s eight movements, there are passages and/or movements in which only one or two musicians are playing. There are also a number of movements in which all of them are playing. But it’s those moments when only one musician plays that are the most riveting to me, both because these solos—on clarinet and cello—are raw and heartbreaking, and because in these moments the other musicians become witnesses. As audience we watch bodies perform, and bodies still and listening. I’m interested in giving equal weight to the bodies that are present but aren’t in a given moment playing.

Quartet for the End of Time, 2017. Excerpt from video documentation. Director/Concept: Susan Silton. Musicians: Erika Duke-Kirkpatrick, Michiko Ogawa, Vicki Ray, Shalini Vajayan. Dancers: Deborah Cohen, Norianna Galindo-Ramirez, Kianna Peppers, Flora Wiegmann. Actor: Cristina Frias. Videographer: Alina Skrzeszewska.

SN: But to extend that a little further, music always implies a context that shapes the sound, while maybe being physically or visually absent. The absence of that context (musicians shielded from view, lyrics, stagecraft, the architecture of the performance site) creates a poetics of experience for the listener. Aware of the relationship between bodies and place, visible or not, suggests an ethics of spectatorship, which is, again, a through-line in your work. This constant relationship between a stimulus and a reception is a way of thinking about more than one—a multiplicity, a community, a public, or a context—through witnessing.

SS: Yes, the site of this work is critical to its context, and to how I want the piece to be experienced and understood.

SN: Right, which is another act of displacement, a displacement of setting in order to produce a different point of view.

SS: Speaking more to that, Quartet began in complete darkness, with an actor, Cristina Frias, standing up in the audience and reciting a spoken word version of a quote from Hannah Arendt, “Even in the darkest of times, we have the right to expect some illumination.” I arranged the words so that they accumulated—they were repeated to grow into phrases, and then into sentences: “Even, even in, even in the…” I also swapped out some of the words for Spanish and Arabic translations. Another kind of displacement of communities that is happening in this city in particular, and in the country as a whole.

Quartet functioned as a prelude to all of the projects that I’ve been doing since then. One work, called A potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past, began with my acquiring a group of original newspapers from the 1930s and early 1940s. Common to all of them is an article about Hitler. I’ve been interested in how the quotidian played out then and the ways it resonates now, for obvious reasons. The pages are framed and juxtaposed with a series of black and white images from my own daily life from the 1980s and 90s. I’ve been sending out a mail art version of this work since January.

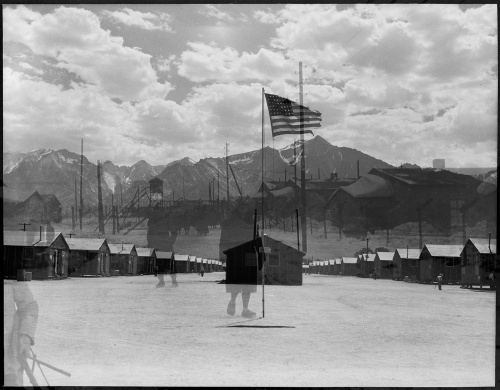

Susan Silton, Montage, 2017. Graphic created for Quartet for the End of Time: Dorothea Lange, Manzanar Relocation Center, Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 1942; Stalag VIII A, 1942. Wikimedia Commons.

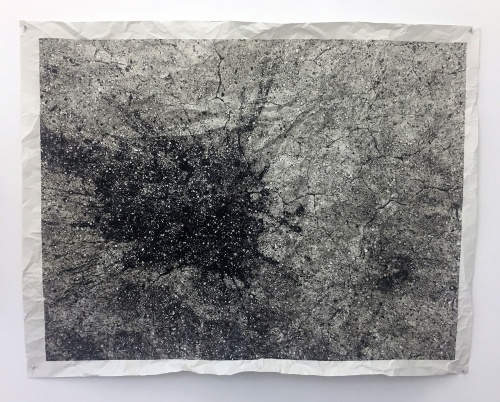

Simultaneously, I’ve been working on a series of images called The stain of________. A stain on________. I’ve found that I’ve been carrying my head low in the Trump era—the bully politics of this time played out in social media, in current political debates about property and place, in the White House, in Congress, pretty much everywhere. I’ve found humanity hard to look at.

And in the process of looking down, I discovered stains on the ground—ordinary stains in the cement, the detritus of our walking, and of our spilling, and of our bodily excretions—the evidence of our being. It’s a question of both beauty and also the darker reaches of our bodies. I have been obsessively documenting stains since then, and I print them large in black and white on a paper resembling newsprint. Finally, I crumple and reopen the prints.

SN: To me, some of them almost look like details from a Miró, like closely cropped details of a splotch, which falls randomly to begin with. For example, in one, there’s what appears to be two paint splotches on the ground, and they’re surrounded by those black wads of gum that have been walked over—the gum turns black—and in the paint splotches, you can see the treads of shoes. These images are like little ciphers to moments that we can’t quite totally recapture but at least have a point of entry into. Do you remember where you found them?

SS: They’re everywhere. I’m finding them everywhere. I’m stopping for them. My hope is that they always do refer to the stain left behind historically, politically, bodily. We are the ones who are responsible for creating stains. I’ve read the word stain so many times since 2016, so I’m interested in giving it form.

SN: When I hear you say that, and I’m contrasting it to the way I engage daily with news or politics and the rapid-fire presence and erasure of information, the major difference is that these stains become incontrovertible records of things that happened—like, it’s really hard to pry up the gum, and probably no one’s going to power wash the paint off the ground. Those miniature events stay on record.

SS: The images allude to all of the stains of history, and to their reverberations in the present.

SN: This is going to seem like a sudden pivot, but I want to make it anyway: One of the very early things you mentioned in this conversation had to do with how that building on San Julian came into your life through the AIR ordinance, which allowed for the creation of artists’ live/work spaces in industrial and commercial neighborhoods—something that kickstarted the kinds of zoning conversions we see today in the creation of the luxury Arts District and the gentrification of Boyle Heights, including its industrial flats we’re in right now.

I’m fascinated with that moment of time because of the way in which something as banal as urban planning found a way to structurally convert the artist as a category, a pass-through instrument for speculation. The artist’s role in this scenario is essentially to recover and recuperate economically unviable locations for a future profit, whether that’s increasing municipal tax revenue or stimulating private investment and development. Even though their occupation is temporary by design, the artist “improves” the real value of property.

SS: Or culture base.

SN: Or culture base, but “culture” is also associated with profit. Similarly, I’m interested in how, at the very high end of the art market, individual works of art are also instrumentalized for temporary use: I may buy a work and I may love it, but it also represents the holding of a huge amount of money that I can exchange later for differential gains.

SS: Right.

#1, from the series The stain of________. A stain on________., 2018–

Ultrachrome print, 40×53 inches.

SN: Having said that and having spent today talking about different forms of art, urban movement, and politics, what are your thoughts on the interaction between artists, art, and markets, particularly with an eye toward change in Los Angeles?

SS: We’re living in a time when the art world is emblematic of the disparity that we’re witnessing on broader levels. There’s the very small percentage of giant galleries at the top and a lot of small, struggling, individually driven or smaller-staffed galleries. The same disparity is seen among artists—not strictly financial but seen in career opportunities. Because in our field, capital translates into exhibition opportunities, which often leads to additional bling. And then of course these days many exhibition opportunities, certainly not all, are influenced by collector capital. We can pretend all we want that the field is filled with independent thinkers who aren’t influenced by capital-based interests in the curatorial choices that are made, even if some curatorial choices right wrongs that are long overdue. Those wrongs should be considered all along, having nothing to do with what’s trending among collectors. The fact is that few deserving artists receive enough, or any, opportunities to present their work. Opportunities continue to shrink in a corporate artworld that is only getting more entrenched and set up both to privilege its own blingmakers, and to create new ones.

We say that this isn’t the only model for success, yet this is what young artists who are in excruciating debt after grad school are clamoring to achieve, either publicly or privately. And this is what so many in our field also promote, from curators, to writers, to other artists. The field is being hollowed out of its criticality and self-reflection in the pursuit of this model for success, a model that began to proliferate as soon as federal support for the arts (and non-profits, and education, and on and on) waned in the 80s.

Most discouraging of all is that this is hardly discussed publicly. Anyone who does is accused of sour grapes. But I think it’s hypocritical and short-sighted to discuss and politically organize against the corporatization of America and not be willing or able to see those same elements driving our field and our communities. I feel that those with privilege in the art world at the highest levels have an opportunity to guide this conversation and should. It makes me think about Daniel Joseph Martinez’ 1988 billboard, “Don’t Bite the Hand That Feeds You.” I want to see artists who occupy the career 1% be willing to bite more.

SN: It sounds like you’re saying there is an existential imperative for artists to investigate and understand how economic and political power coalesces within a very small, privileged community that expends that power only to those who conform to its values. As a corollary to that, there is an imperative for artists to understand how speculation—betting on future profit in the hopes of securing personal success—is an operative mechanism of our time, and how artists themselves are heavily implicated in the displacement that causes.

SS: I would say the art market is implicated in displacement, and artists are implicated in their embrace of corporatization, either enthusiastically or with heads in the sand. So, the growing disparity isn’t addressed. Look, I first lived and worked downtown at a time when we cohabitated with, not displaced, the communities that had preceded us. Displacement has always happened and will continue to. But the speed at which that happens in a climate of haves and have nots, is striking. Though industrial buildings were changing hands and being transformed into lofts over several decades, this game changing iteration of downtown development happened just eighteen years ago when developer Tom Gilmore spearheaded the effort around 4th and Main. Think about everything that’s happened in that span of time. This latest boom is very different in feel, flashier, more visibly hypercapitalized than when I lived here. And the homeless encampments just blocks away are more visibly expansive, too, the other side of that flashy coin. Is it a positive thing to have downtown be a viable, inhabitable city-center? Absolutely. But why is Rodeo Drive-like retail, or the Hauser-Wirthification of culture our only options?

SN: The other thing you seem to be suggesting is that there’s an imperative to renegotiate the end goal and actively question what success looks like: Is the end goal fame? Is the end goal spectacle? Is the end goal the accumulation and hoarding of resources so that you as an individual can do whatever you want? Or is there something else? Those questions could be answered by the individual, the gallery, the museum, the university, the community; they can and should be asked at many levels simultaneously.

SS: I’m suggesting that where our complicity truly lies is in allowing this disparity to be acceptable and channeling our energy towards striving to be in that 1% so that we can survive as artists, gain recognition for our work, be annotated in the art historical canon. But I accept that it’s challenging to enact change when fundamental models, whether they are for infrastructure or for success, are dictated by those at the very top.

Here’s a notable example. Some time ago, I read an article about directors from two mega galleries embarking, in a self-congratulatory way, on a commitment to financially support younger, smaller galleries to be able to participate in one of the major art fairs. International art fairs have become the branded mechanism by which art is sold, all but replacing galleries. But as one subhead in a Vanity Fair article noted a few years ago about one of the fairs: “Frieze, the London art fair, isn’t about art. It’s about rich people—really rich people—and a market created for them.” Art fairs have been just one of the contributing factors to the corporatization I’ve mentioned. Their expense has made it either impossible or extremely challenging for smaller galleries (and as a result their artists) to be part of this economic model, which privileges the higher-end galleries, which can afford bigger booths, which attracts more collectors, which generates more sales.

So here are these two directors representing high-end galleries responding to art fair inequity by suggesting top-down support, rather than what they might have done, which would have been to question and either reject or strategize alternative, less inequitable models for selling art before art fairs became the standard. The top-down model equals the corporate model.

SN: Bring other people to this system that has already defined us and produced an elite group of the successful few.

SS: Exactly.

SN: It seems like one way of counteracting the complicity—going along within an activity as long as it raises your professional standing, profile, capital, whatever—is to require and insist on an investigation of consequences. If you say there are no consequences for your actions except for your own success, you’re kind of missing the point.

SS: Yes. As a species we tend to ignore consequences. We are intrepid seekers of knowledge and movers forward, we want to progress, but in our progressing we fail to evaluate our actions until it’s too late. This tendency has played out over and over again throughout history. An era of complicity requires an awareness of consequence. In the end, I still want to hold out hope that artists can be at the forefront of speaking truth to power, of transforming consciousness into concrete action at a time that feels so much like we’re on a runaway train.

Susan Silton, A potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past, 2019, detail. One of five mailed reprints in plastic sleeve