Second Life: Making WET

by Leonard Koren

This is an excerpt originally published in Making WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing (Imperfect Publishing, 2012).

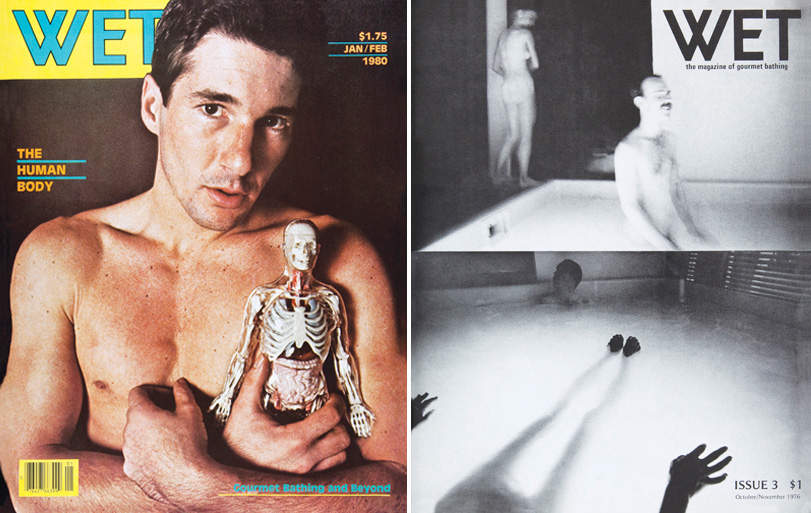

WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing was founded in 1976 by UCLA Architecture graduate and self-described “bath artist” Leonard Koren. Subject matter initially included anything remotely related to bathing: sweat, yoga, toothpaste, hot tubs, ecstasy, and mudbaths; by the end of the first year, this expanded to “gourmet bathing and beyond.” WET provided a distinct counterpoint to Warhol’s Interview in New York City, drawing on creative forces in and out of the Los Angeles art world and placing a strong emphasis on the graphic. But while Interview might best be described as film journal meets glossy celebrity tabloid, WET remained a more experimental publication in both form and content. At its core was playfulness, an appreciation of the absurd that kept WET constantly fresh during its five year run. In the words of one subscriber, “WET is the closest thing so far to a total vision of the present. It creates and is created by everything that is going on right now.” Koren recently published Making WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing (Imperfect Publishing, 2012), an illustrated history of the short-lived but influential magazine, and shares his thoughts on the birth of WET in this excerpt below.

WET: A Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. Left: Issue 30 (March/April 1981). Cover illustration and design by Bob Zoell. Art direction by Leonard Koren. Right: Issue 19: Outlaw (July/August 1979). Cover photograph by Larry Williams. Design and art direction by Roy Gyongy and Larry Williams.

WET: The Magazine of Gourmet Bathing was published between 1976 and 1981, mainly in Venice, California. Altogether there were thirty-four issues. During its spirited five-and-a-half-year assault on good taste and linear thinking WET was often lauded as “smart,” “funny,” and “inspirational” by its international readership of artists, designers, and like-minded creators. Subsequently, nearly all of its conceptual and graphic innovations were absorbed into our common visual and media landscape.

WET’s philosophy of bathing, however, has made only limited cultural inroads. Its basic tenets are:

~ Water, steam, air, and mud—and the energy to heat them—are precious resources to be cherished and conserved.

~ Cleanliness is next to impossible (but keep trying anyway).

~ Nakedness is almost always an excellent idea.

~ In addition to all its other charms, bathing is an accommodating metaphor.

WET never took itself all that seriously. To paraphrase one of its contributors, WET was a parody of all enthusiasms, or more accurately, a parody of all enthusiasms taken a bit too far. WET’s most endearing quality was its wholehearted embrace of the absurd. Each and every issue wrestled mightily with seriously silly propositions: Workable Extremist Thinking. Waste Everything Twice. We Eat Tuna . . . Take your pick; paradoxes and non sequiturs were eagerly served up. WET’s underlying agenda? Upping readers’ tolerance for ambiguity and contradiction, i.e., fostering a greater appreciation of the reality of reality.

On the following pages are bits and pieces of what once constituted WET’s editorial playground. Most of the emphasis here is on bathing, the magazine’s ostensible subject matter. WET was, of course, about much more.

PRE-WET

People often assume that I’ve always been interested in bathing. But this isn’t so. My fascination really only began while in architecture school. Like most of my classmates, I was initially drawn to the heroic architectures du jour, Modern—the taut, muscular variety—and then proto-Postmodern. When those love affairs soured, I became curious about less self-conscious, more humane approaches to place-making. This led me to small, intimate environments: the kinds of places you go to feel safe and secure, the kinds of places that induce you to “let go” and “be yourself.” The Japanese tea room—despite its very appealing form and philosophy—was too culturally specific for the vague purposes I had in mind. I sought a species of enclosed space that offered similar possibilities for transcendental experience but was more universally available.

That’s when I discovered the bathroom. Bathrooms are everywhere. Just about everyone has one. And every bathroom, no matter how crude or sophisticated, comes equipped with all the elements of a primal poetry:

Water and/or steam.

Hot, cold, and in between.

Nakedness.

Quietude.

Illumination.

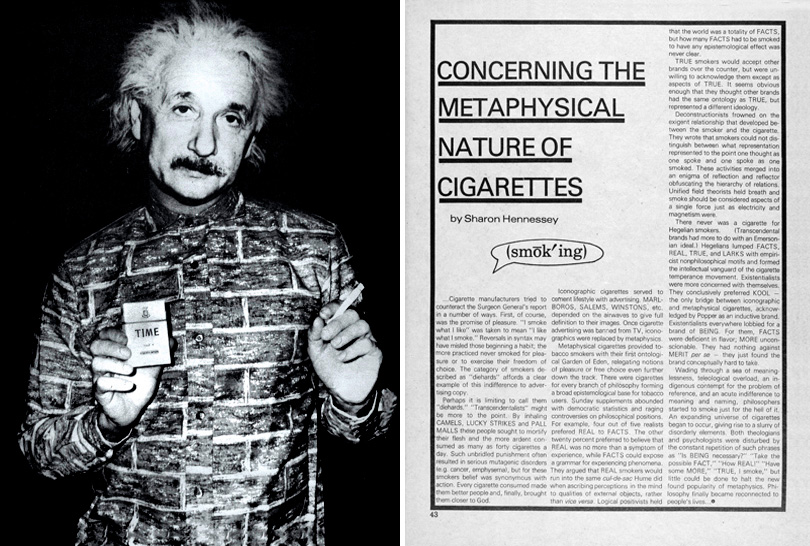

WET: A Magazine of Gourmet Bathing, Issue 21 (November/December 1979). Left: Photo-illustration by Larry Williams. Right: Sharon Hennessey, “Concerning the Metaphysical Nature of Cigarettes.”

AMBIENT INSPIRATION

During my last year of architectural study, I lived in Venice (California) in what had originally been a gondola garage. Venice, like its Italian namesake, was once crisscrossed by canals. When the waterways were filled in and paved over, this sprawling structure was converted into an automotive repair shop. Eventually that business folded and the complex was purchased by a trio of artists who divided it into three live-work spaces and an apartment, where my girlfriend and I resided.

One of the artists, Peter Alexander, had a trench-like depression in a section of his floor. It was a long, narrow grease pit that had once enabled mechanics to work underneath cars and trucks without having to jack them up. Peter painted this concrete void white, then filled it with water; the water was recirculated through a swimming pool filter and heater. A skylight was installed overhead with small prisms positioned along its sides. On sunny days rainbows washed across the trench and its shimmering surface.

In an adjacent studio, artist Jim Ganzer chipped away at his concrete floor until he reached the dirt underneath. Over a period of years he reclaimed a twenty-five-foot circle of earth into which he placed tropical plants and banana trees. Gravel and rocks, big and small, were scattered in the spaces between. Then Jim punched holes in the roof to let natural light in and the trees grow out. He installed shower heads high up near the ceiling. Whenever Jim wanted to water his garden he simply took a shower.

GESTATION

By the time I had completed all the coursework for my master’s degree, architecture was the last thing on my mind. I was off in a different direction. I was making bath art. This involved getting people to take off all their clothes and then bathe, according to my detailed instructions—in either water, mud, hot air, or steam—while I took photographs. Afterward I assembled the images into more complex visual artifacts, usually lithographic and silkscreen prints. I sold these in galleries and through word of mouth.

The models for my various projects were mainly artists, and all of them had modeled for free. I wanted to reciprocate for their kindness and generosity, but I had little money. A “thank you” party felt like a good solution. A friend suggested I check out the Pico-Burnside Baths, a down-at-the-heels Russian-Jewish bathhouse midway between downtown Los Angeles and the beach. Once inside I was immediately charmed by the authentic retro ambience, down to the mismatched wall finishes and the lingering smells of Eastern European delicatessen foods.

The manager quickly let me know that mixed-sex bathing was absolutely forbidden. But what the hell. He offered me the entire facility—a sauna, two steam rooms, a swimming pool, a whirlpool, snack and changing areas, and a weight training space—for $450, provided I cleared everyone out by midnight. I calculated I would need an additional $200 for refreshments; I had friends who could cater at cost. And I knew an electric jazz violinist who might play if I offered him $100 or so. It was well over my budget, but since the place could accommodate at least 150 people, and I was obliged to comp only about 70, I figured I could invite other art-related types, charge them for an unusual experience, and cover all my costs.

WET: A Magazine of Gourmet Bathing. Left: Issue 22: Human Body (Jan/Feb 1980). Cover photograph by Larry Williams. Design by Paula Greif. Art direction by Elizabeth Freeman and Leonard Koren. Right: Issue 3: Bathe in Nothingness (November/December 1976). Cover photograph and design by Leonard Koren.

The party came at the end of an exceptionally sultry late-summer day. Angelinos, tan and tight after the discipline of three months in a bathing suit, were unusually primed for something new and edgy. And that’s what they got. The next morning the buzz around the art and design communities was “You should have been there!” Then the Los Angeles Times ran a long, gushy feature on the event. Included was a photo of me shaking hands with fashion designer Rudi Gernreich, the creator of the monokini, a.k.a. the topless bathing suit. Gernreich was elegantly attired in shoes, slacks, and a sweater. I was barefoot, a flimsy yukata clinging to my torso. This ramped up the hyperbole and myth-making to an extraordinary level. By the end of the week even I was deluded into thinking that a new (arty) context for pleasurable social interactions had inadvertently emerged. Conventional norms of party behavior appeared to have been upended, or at least temporarily suspended. Things were definitely going my way.

How, I wondered, could I exploit this unexpected turn of events?