68/99

by Robby Herbst

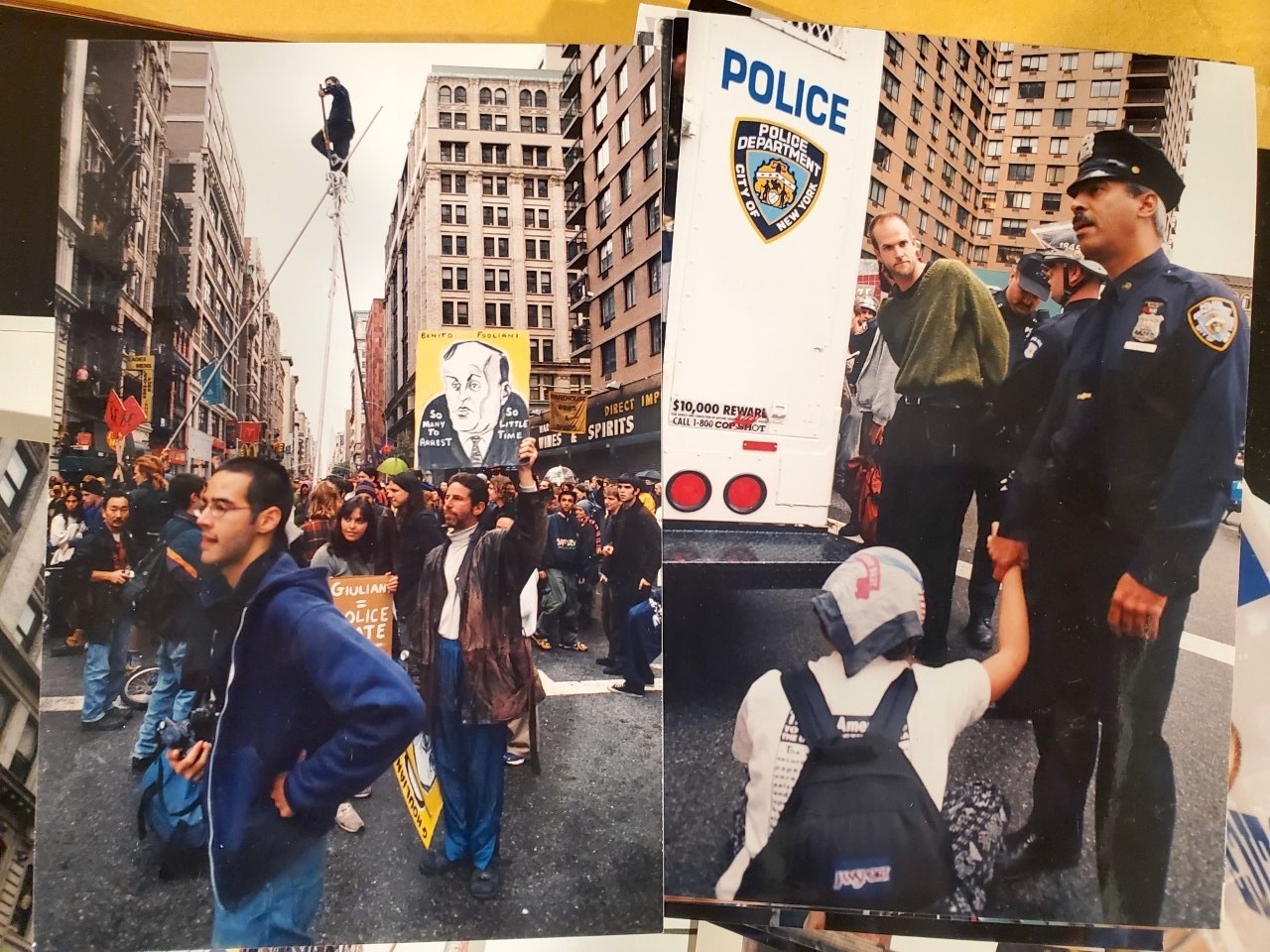

Reclaim the Streets (RTS) protest, New York, NY, June 18, 1998. Photo: Dave Murphy

Flaneur

Arriving at CalArts with politics, as I did in the late 1990s, felt weird. Maybe it’s always like this? At the time the real practice didn’t fit the theory, or was it the other way around? I was accepted to the Art MFA Program just as I was starting a job as a tenant organizer in the Northwest Bronx. An if-then clause I composed for myself was, “If art school is a privilege, then art school should be a privilege for anyone in a just society.” I didn’t give much pause to the cost. Tuition in the ‘90s wasn’t that large a sum yet, and the accepted word was that grad school debt was an investment in your future. In my mind, I was heading to California to think about stuff, make stuff, and learn to think about making stuff; in turn I would contribute all this to the remaking of the world. The whole time I was at art school I didn’t think about selling art once. When pressed about the reality of economic survival I’d say I was aiming to get work teaching college. So, I quit the organizing job knowing I’d be heading off to get my MFA in September. I didn’t want to find myself arm-deep in a heated campaign against a slumlord only to jump ship suddenly for sunny Southern California.

I didn’t take too many classes when I was at CalArts, because there weren’t too many that spoke to me. I read, and talked, and looked a lot. I made art that faculty and classmates seemed to enjoy. We were good. However, during my third semester, in the fall of 1998, I re-enrolled in Michael Asher’s Post Studio critique. I’d taken it the year before, as a first year MFA. I enjoyed engaging with Asher, who was known for his endless chat sessions. I recognized his line of inquiry, which addressed a student’s art, and generally circled around a dogma which I could identify but had no allegiance or fear of, whether that was his minimalism or his post-Greenbergian Marxist cultural politics. But Asher was on leave that semester, so the Art Program hired an Asher-approved sub, William E. Jones. All of my classmates were enrolled. We were keyed up to bond over eight hour critiques.

I knew my politics. I was an anarchist uniquely aware, I felt, of the differences between the entrenched aesthetic politics of artists like Asher, and the populist strategies of vanguard, culturally-oriented political movements. I was also attracted to CalArts because of my perception that it danced with popular and populist movements—the Feminist movement, the counterculture, and punk. I’d spent time living in the Jonah House in Baltimore, the commune (for lack of better word) founded by radical Catholic pacifists Philip Berrigan and Elizabeth McAlister. I’d worked with both the countercultural San Francisco Mime Troupe and the eco-civic socialists of In the Heart of the Beast Mask & Puppet Theatre in Minneapolis.1

Before moving to Los Angeles in 1997, I had been living illegally in a Brooklyn industrial building with my buddy Dave Murphy. He was cutting together a 16mm documentary film using a Steenbeck flatbed editor there. The film was called Free Ride and it was about a group of neo-hobos who were also eco-anarchists participating in blockades in Oregon’s old growth forests. In the other corner of our space in Brooklyn, we’d put together Radio Dumbo, a pirate radio station that we programmed three nights a week. We were broke, so our entertainment consisted of following the much more established squatter and micro-radio scene, which centered around Steal This Radio across the East River in Manhattan’s still grungy Lower East Side.2In all of these instances, it was obvious that politics had a form and limiting its visual dimension meant limiting its political horizon. I was curious about the nature of all of this and Asher’s Post Studio provided a venue to debate some of these tensions around formalism and its value. In my memory, Asher valued it little, whereas I was definitely curious. But the conversations were pleasurable and never personal, even when Asher dismissed a conversation I premised on pop painter Wayne Thiebaud. The lines we drew around what and how we talked—that was interesting, and drawing those lines was useful.

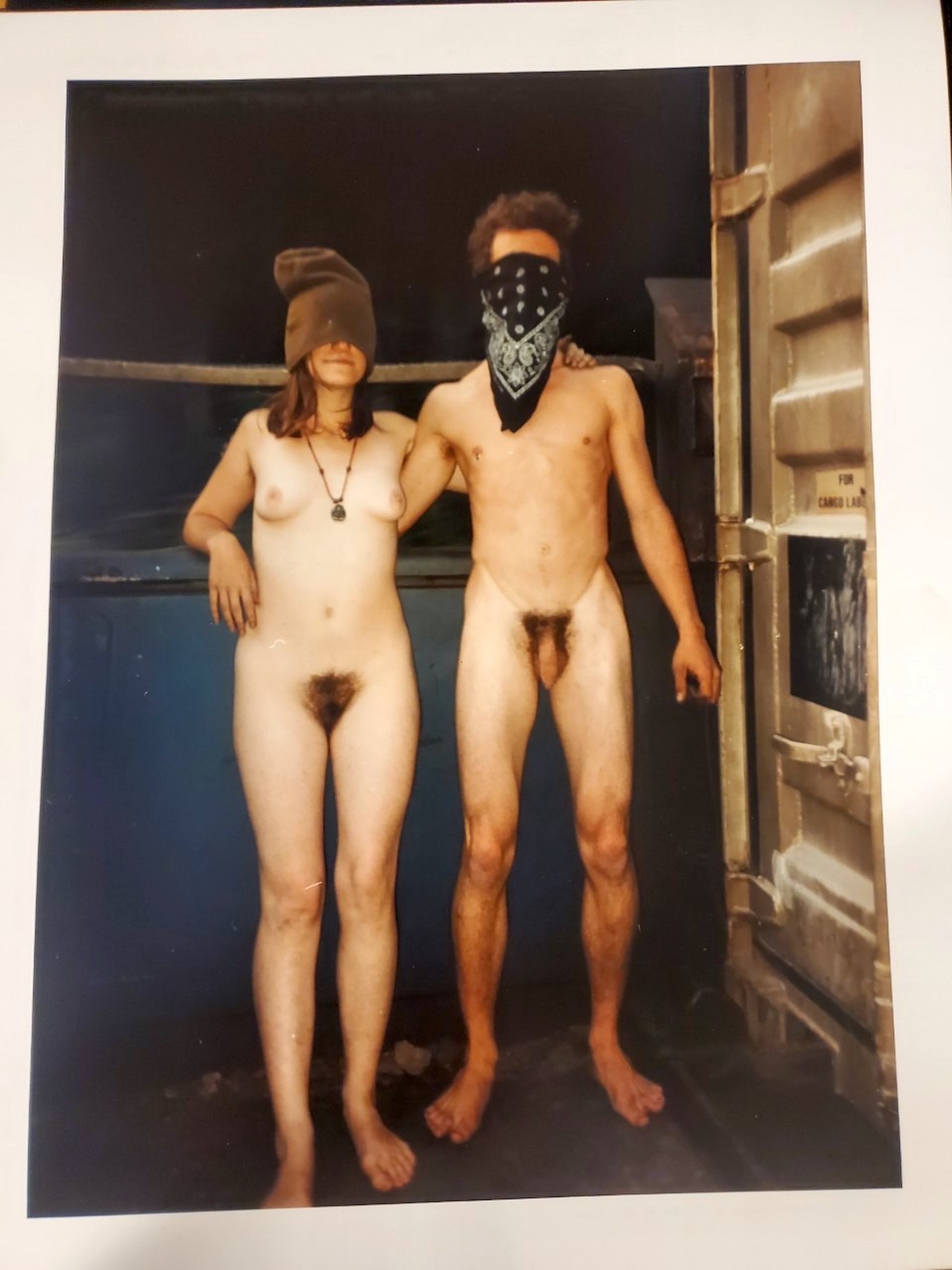

Production stills of naked anonymous freight train riders from the film Free Ride, 1997, 35 mm, proof sheet print. Photo: Dave Murphy

The second time around, with Asher’s substitute, wasn’t so useful. What I knew about Jones was that a few years back he’d been a favorite student, and also he made structuralist films about gay pornography. I’d hoped to find something overarching to share with someone assuming Asher’s mantle. Jones was ten years older than me, and I guess I imagined we’d both be interested in cultural subversion. In the intervening years I’ve come to admire his films and writing, but at the time I wasn’t a fan of his critiques. He had a hard time holding a meaningful center to the conversation.

In Asher’s class that first year, I shared an installation I’d done right before coming to CalArts. It consisted of a variety of cast plaster eyeglasses of varying styles. I’d made work like this since leaving the puppet troupe in Minnesota. At the time I was in the habit of referring to a certain style of Oakley brand mirrored sunglasses that wrapped around your head as “asshole glasses,” and the people who wore them as “assholes.” The other frames in the installation were common and inoffensive. Within the installation the glasses were painted different colors and placed in different locations and heights. The objects’ relationships set up a story about walking around Valencia Street in San Francisco during the mid ‘90s. I forget all the important specifics, but I remember there was a struggle happening between the objects in the installation. For a full Friday afternoon, Asher was able to entertain this whole conversation hinging on what was essentially class and style signifiers hiding in a narrative sculptural installation. He even adopted my term “asshole glasses” for the critique’s duration. My friend Lize Mogel still delights in this memory of Asher saying “asshole glasses.”

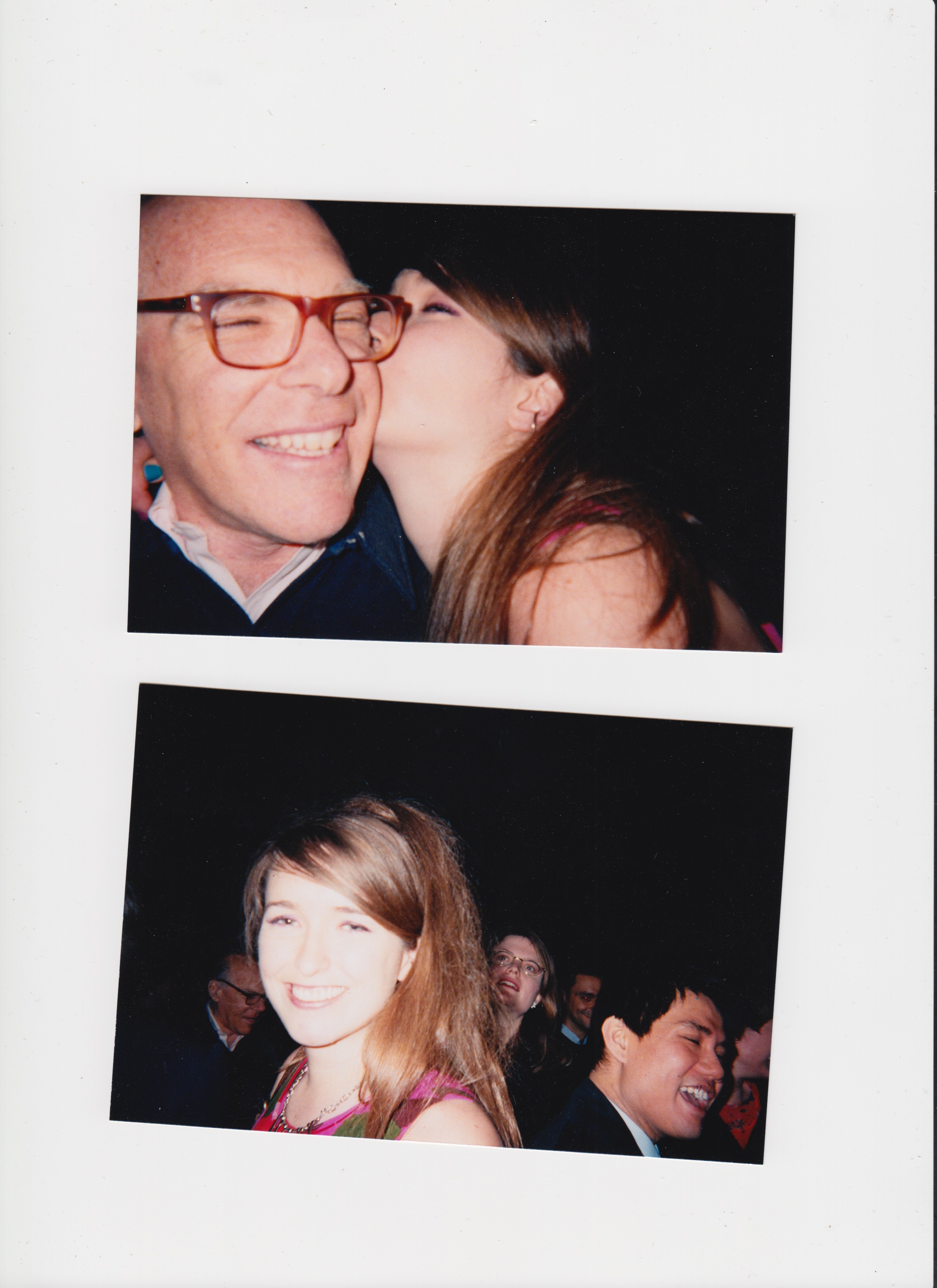

Michael Asher and students at CalArts graduation ceremony, circa late 1990s. Photo: Mark Allen

Jones, on the other hand, didn’t have this kind of critical flexibility. He was not entertained by my fashion, nor by my classmates as a group. I remember he wore a butch black uniform—black jeans and a black t-shirt. I tended toward thrift store fashion from the 1970s—a cheap gimme cap and motorcycle boots or chunky Fluevog shoes. Near the end of the class one day, I remember him asking me how I could ever wear a pair of polyester, gray-checked, wide-legged pants. Then he abruptly ended a student’s critique and declared that my entire cohort of MFAs was nothing but a bunch of “dilettantes.” As a student, I was taken aback. But as an artist, I loved this—to me a dilettante was essentially a flaneur. Just about a month previous, I’d been back in San Francisco and purchased a thick copy of the Situationist International Anthology at Bound Together Books. To me being declared a flaneur, someone who drifts through life looking for senses, was yummy.

Generation X

My father was an art student at Cooper Union and then NYU in the very early 1960s. He liked to say of the paintings he had around when I was growing up, “If you don’t get it then I’m not going to explain it to you.” The modernist painter Hans Hoffman was his teacher. My father had swallowed the Greenbergian line.3I did feel something from his paintings; it was a weight. I was always hoping to be spoken to—told the meaning—by the gathering of colors and shapes in his work. For me, making narrative sculptures, artwork that aimed to speak to you through color, shape, and form, was a huge breakthrough given the militancy my father held for the value of abstraction and the sublime. When I reflect on this, it explains my interest in thinking about making stuff, rather than just making stuff. To this day I find that I still do this double-time, speaking the quiet parts, conceptualizing the creative impulse, verbalizing silent yet collectively held socio-political trajectories. In the 1990s, it felt like there could be a space for this kind of talk amidst the broad and relatively disorganized independent culture sectors that were practically hiding everywhere then. Leaving home I spent time trying to stitch this worldview together in my mind.

David Herbst, title of work unknown, circa late 1960s, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 49 inches. Collection of Nancy Herbst.

Leather Tongue and Naked Eye were video and zine shops in San Francisco.4There was another great zine store, whose name I forget, in Baltimore, where I bought the first issue of Crap Hound.5Comic Relief in Berkeley was a comic book store where they sold back issues of 1980s and early ‘90s underground comics at cover price. You could buy all of Fantagraphics’ new titles there, too. Rainbow Bookstore Cooperative was a place where I volunteered for two months when I lived in Madison, Wisconsin with two roommates. I penned and read my first art review on air for Madison’s community radio station WORT. When I got to Minneapolis I didn’t have time for books or zines, but I bought a Stereolab album and browsed the leftist posters from the Northland Poster Collective’s shop on Lake Street. You had a choice of several food co-ops in that town, and folks still talked about the armed conflict that broke out between them a few decades earlier. As you can imagine, Northampton and Amherst, Massachusetts had superb independent cinema, video shops, and zine, comic, and bookstores. In Amherst I realized that the excitement I felt purchasing a book about women in the Zapatista Rebellion was the same excitement I felt talking about the indigenous struggle with my friends.

The first theoretical writing I really “got” was Frederick Jameson’s writing about Fordism and postmodernism. I was lucky because, just before I went off to college, I’d read the it-book Generation X by Douglas Coupland. Its postmodern ennui spoke to me the same way Jameson did; I got that it described my world. Being an artist, I wanted to change these conditions, not describe them. But there wasn’t much contemporary art that addressed this, and neither did much of the theory circulating at the time.

Black Out Books was an anarchist collective bookshop in Alphabet City, in Manhattan. It was bound to the strong underground currents of the neighborhood—housing rights, environmentalism, anti-capitalism, free-speech, drug law reform, Puerto Rican liberation. They carried some of the de rigueur postmodern theory, Derrida, and the flashy Baudrillard. But they also carried inexpensive Xeroxed copies of revolutionist stuff and published books by more esoteric writers—Critical Art Ensemble and Hakim Bey in particular.6These works were different. They focused on strategies for making different histories rather than dissecting it.

When Thomas Frank came to speak at CalArts about his anthology Commodify Your Dissent, my classmates and I were thrilled. I read his zine, The Baffler, and enjoyed its nostalgic workerist cultural criticism. I was grateful for its voice. But I remember the thrill of having the opportunity to challenge Frank and his publication from the left. I didn’t have exactly the right language then, but essentially my line addressed the cynicism of a cultural critique that focused on selling the affect of rebellion by the capitalist cultural industry, and that was published in a magazine supported by a network of independent cultural industries. I was interested in the function of radical affect as a phenomenon, not who got to sell it. Formally, the differences seemed small if the outcome could be the same.7

Deleuzers

Robby Herbst, Hippies, mid-res exhibit at CalArts, plaster, acrylic paint, 1998. Image courtesy of Robby Herbst; Hippies was a sculptural installation of 140 or so cast plaster and plastic figurines whose positions told an idiosyncratic story of social movements.

During my time at CalArts, the seated theorist was an academic performer who taught courses on French theory named Sande Cohen. He called his favored students “wild man,” and I was proud to have earned this nickname, though I wonder now if there were ever any “wild women.” I didn’t take his course for a grade, but I perused the assigned readings and showed up for class to participate in the show. With his stringy long hair and impish grin, he gave off a revolutionary vibe, but for him praxis had been foreclosed upon. I interpreted his narration of contemporary philosophical history like I would a tombstone. While Cohen’s take wasn’t quite Francis Fukiyama, for whom the fall of the Soviet Union in that decade signaled an “end of ideology” and capitalist triumphalism, it may as well have been. I knew that there were many simultaneous histories, that politics was more than a spring in Europe or Marx writing in a garret. But to Cohen, Guy Debord was just a colorful footnote who influenced Baudrillard. To him it was Baudrillard who did the real work, analyzing the condition of our simulated hypnosis rather than the possibility of escape from it. I aimed to develop with him an independent study addressing the philosophers Herbert Marcuse and Norman O. Brown, two writers he’d discussed as having influenced the American counterculture. I imagined this would be an easy ask; I knew of Marcuse’s historic relationship to CalArts.8But although he encouraged a summer letter exchange between us, he didn’t think this study was worth his time.

Charles Gaines directed his ‘Content and Form’ course with softly murmured philosophical reflections on the writing of Jean Francois Lyotard, Deleuze, and Guattari. I enjoyed his incantations. Rather than mastery over the texts, he encouraged liminal readings that skimmed uses from them. He discussed linguistic theory—signs, signifiers, synecdoche, metaphors, metonymy—long chains of relationships which confounded logic. Cohen had introduced me to these thinkers, but Gaines’ creative prompts applying the post-structuralists’ ideas towards constructing language forms, rather than just deconstructing them, was eye-opening. I remember a prompt of his involving a misdirection of impossible interpretations—something akin to the fact that cats, dogs, mice, and humans can co-exist in the same building and share the phenomena of oral communication, yet they are unable to speak between species. Or what about the fact that we have five senses—sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch—but can’t use visual interpretations to translate non-visual phenomena; why can’t we apply color to a flavor, or sing out a smell?

One of the things I found attractive about Gaines’ discussions was his discourse on binary oppositions and their emphatic constructions that limit the social, political, or creative imaginary to a fixed set of given terms. Either/or scenarios, like “black or white,” by nature exclude everything else, including non-identification, misidentification, and what theorist José Muñoz came to call disidentification. Gaines’ discussions, which related to the construction of identity and the identity-based artworks that appeared to dominate political art strategies from the recent past, were a breath of fresh air.9He was interested in us challenging fixed linguistic and political hierarchies. This not only reflected my real world experience as an activist, but also my experience doing old school political theater, which largely built narrative tensions through essentialized characters, characterizations, and political scenarios. To construct political artworks without relying upon ready-made linguistic strategies seemed like a worthy challenge.

Gaines had been developing ‘Content And Form’ for years, and he carried around with him a notebook with all his notes on the books he taught. When his car broke down, Kimberly Varella, who was in the class with me, recalls Gaines saying that he used his notebook as a tire stop, so the car wouldn’t roll away. Once his car was fixed he drove off, forgetting the notebook, and the notes blew away. What we were getting in his classroom was therefore constructed from remembered notes of books he readily admitted not fully getting, notes which were scattered somewhere, I imagine, on the side of I-5. I liked this happenstance as it was ripe with openings that I wasn’t getting elsewhere. The era’s creative gestalt, conditioned by an interpretation of postmodern theory’s impulse to catalog references in a never-ending cascade of mirrors of Plato’s Cave of shadows, had the penchant to overly determine, and kill, art. By using post-structuralism to accept a finiteness of language’s effects, Charles welcomed affects.

Two artworks produced by fellow classmates personified this for me. The first was a sound piece made by Erik Snyder, then an undergraduate student.10It was exhibited in the L Shape gallery, a highly trafficked corridor of the Main Building and the most accessible of all the galleries on campus. The work consisted of an audio clip of a Beatles song on infinite loop, the melody revving up and then falling off… “All you need is love, love is all you need”… an assertion and then a declension reverberating off the walls of the school for a week. The clip was intriguing and lingered in my mind as the days wore on. The reference was unavoidable; it was an agreeable truism—“All you need is love.” But then it was down beat—“Love is all you need.” You’d begin to think to yourself, “Hey, didn’t you just say that the opposite way?” Then there was our collective memory. We’d grown up with this countercultural artifact; broadcast repetitions had hammered it into our brains until it was rendered meaningless blather, like the slacker chorus verse that echoed “yeah, yeah, yeah.” But then the clip would loop and you’d hear it again and the truth, “All you need is love,” was a forthright annunciation still. It would always be so, if you heard it right, regardless of how the echo inevitably mutated its original meaning. A truism would always be accompanied by the accumulation of knock-offs. One did not negate the other. “Love is all you need,” “yeah, yeah, yeah.”

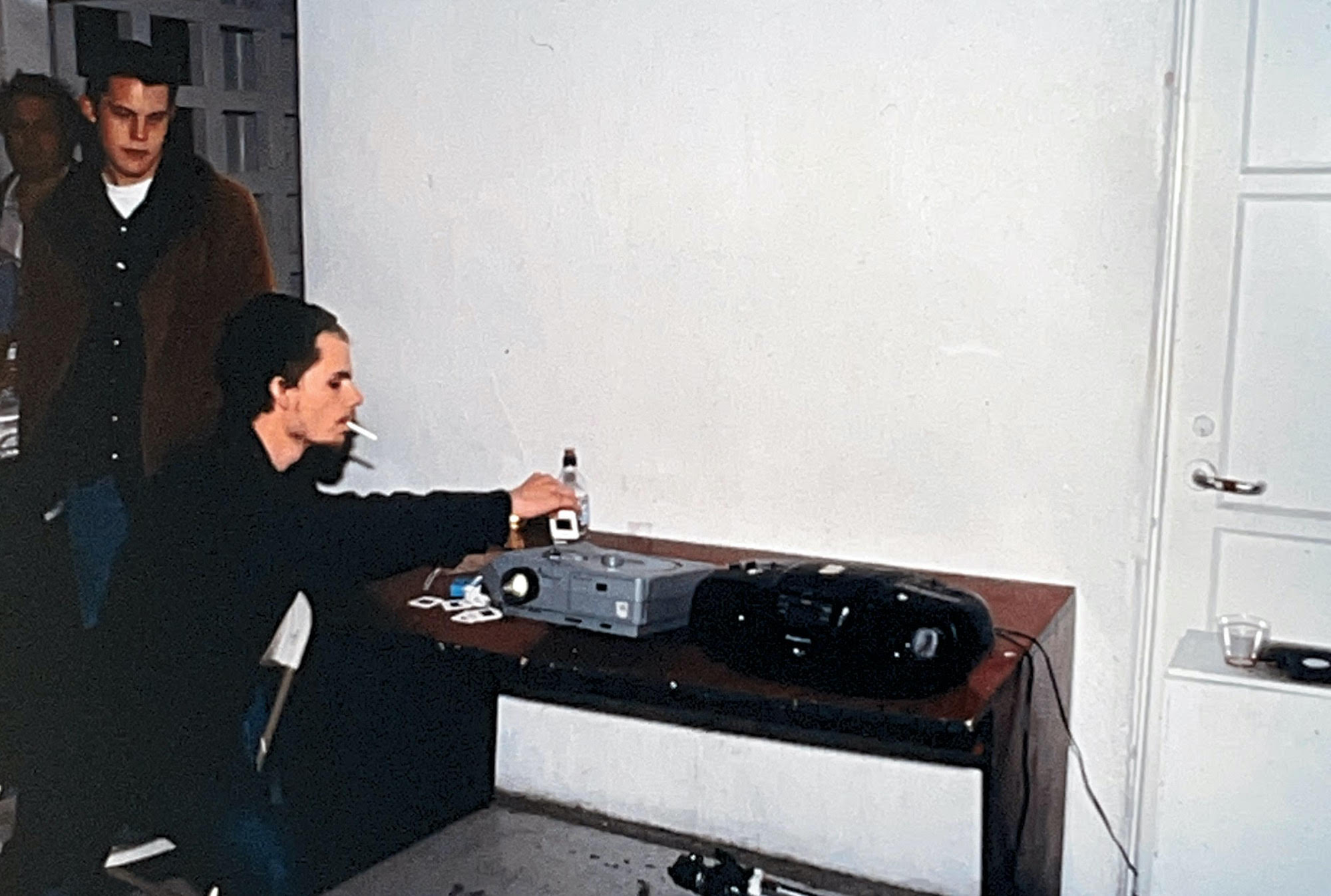

Eric Snyder, participation in Karen Finley class show, CalArts, 1999. Image courtesy of Robby Herbst

The second artwork was a sculpture and sound piece made by our classmate John Williams. It too was constructed from artifacts—an old turntable, cheap commercial records, and a common desk lamp. Like John Cage’s prepared piano, Williams had applied objects to the records and modified their presentation to alter the way we experienced the sound. He’d strategically placed tape or wire to make the needle skip and slide, and he projected the light through stage gels and mylars that he’d affixed to the records in some way. Visually, the assemblage looked junky and odd, but the rotation of the turntable caused a variety of fantastic light effects and intriguing, sometimes catchy, audio riffs as the needle skidded around on the records. The metonymic transference in this case was inescapable. Our postmodern garbage had been transformed into a sight of color, light, sound, wonder, and pleasure.11

John Williams, Record Projection Table, 1998. Slide projector, record players, wood, speakers, 7” records, and mixed media. 72”L x 60”D x 30”h. Photo by Joshua White.

By the time we were finishing our short grad school experience in May of 1999, many of my classmates were talking about what comes after postmodernism, a post-postmodernism? Someone speculated that postmodernism was a temporary stage to new modernisms. This excited us. For me it held out a promise to construct rather than just deconstruct. For our graduate show, held next door to what is now a Blue Bottle café in the historic Bradbury Building in downtown L.A., I showed a large carved foam sculpture where the years 1968 and 1999 were 69ing. It was clear to me how the past rarely went anywhere despite how it was historicized.

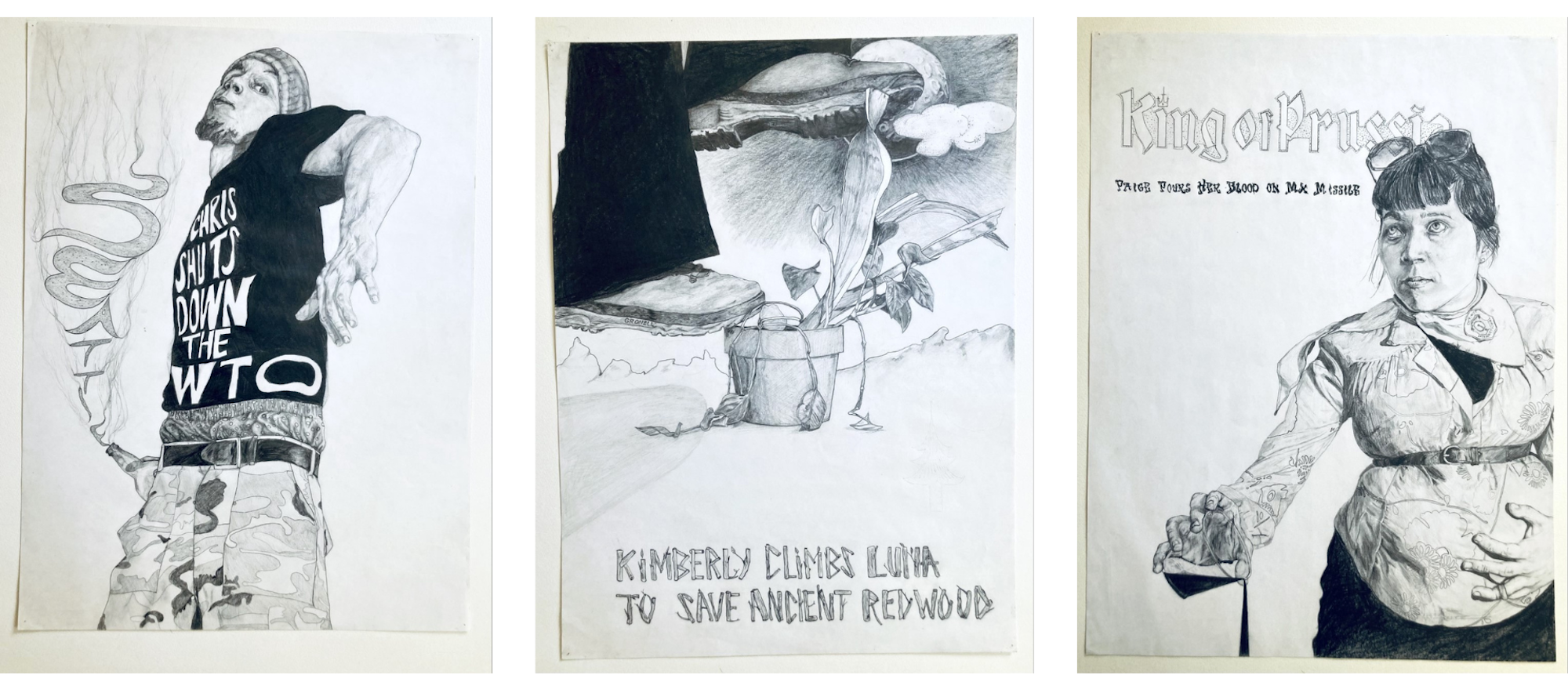

Robby Herbst, from left to right: Reenactment Drawing (Chris Shuts Down The WTO), Reenactment Drawing (Kimberly Climbs Luna To Save Ancient Redwood), Reenactment Drawing (Paige Pours Blood On MX Missile). All drawings completed just after graduating CalArts, circa 2000, pencil on paper, 18 x 24 inches, featuring Cristopher Cichocki (Art BFA ’01), Kimberly Varella (Art MFA ’99), and Paige Clark (Art MFA ’99). Friends of the artist were given documents relevant to direct-action political activities and asked to reenact that event in a studio environment. The performances were photographed and then redrawn. Images courtesy of Robby Herbst.

Sources of Heat and Light

In November of 1999, my twin brother Marc and I drove from L.A. to Seattle to participate in a series of direct actions targeting the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Ministerial Conference in Seattle. While I had just graduated from CalArts, my twin had just enrolled. I thought it was cute when he checked in via payphone with his first-year advisor from the road. They approved his absence. We arrived at the protest a few days early to help my friend Dave.

Through the micro-radio community, Dave had gotten involved in organizing what eventually became IndyMedia.org.12Dave brought us to an Independent Media Center (IMC) space and caught us up with the surprisingly huge and inspiring infrastructure that was in the works to support, and abet, the actions. We spent the majority of our time there reporting from the streets and filing audio stories for the IMC. Dave introduced us to folks who were running activist communications and others who were planning spectacular banner drops. And he introduced us to the Direct Action Network’s dynamic hub space on Denny Street, where they were welcoming protesters from around the world, catching them up on the actions, and puzzling them into a plan that had been collectively developed to shut down the gathering of the globe’s most powerful leaders.13

Teamster protestors in sea turtle costumes at the 1999 World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference, Seattle, WA, November 30, 1999.

For the individuals who attended the “Battle in Seattle,” it’s frequently remembered as a life-defining event. It was generational and mythic in many ways; one myth holds that the IMC’s illegal micro transmitter was located in a downtown high-rise apartment owned by one of Nirvana’s surviving members. I knew the blockade would be successful. My friends and I had been following the collective actions and blockades of Reclaim the Streets in the U.K. for some time.14Its weaponization of Emma Goldman’s declaration regarding dance and revolution was faultless. Not dissimilarly, the gas-masked and militant marching band Infernal Noise Brigade gave courage to demonstrators in Seattle.15Their schtick was flawless Gesamtkunstwerk. They were just as intimidating, armed with instruments and choreography, as the cops were with battle armor, batons, rubber bullets, and gas launching rifles.

The “Black Bloc” protestors at the 1999 World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference, Seattle, WA, November 30, 1999. Photo: Gerald Ford

If I’d been given a chance I would’ve placed a $2000 bet that Woodstock ‘99 would end the way that it did—the affect of popular music at the time was unavoidably pissed off.16This alienated, rebellious spirit within youth culture found a clear target in Seattle. My favorite oddball memory is one of a skateboarder who journeyed downtown just so he could ollie over burning trash bins. When members of the Black Bloc addressed the breaking of corporate store windows by Seattle insurgents during the ministerial shut down, their communique included a litany of poetic verses suggesting that shattering a window with a hammer was a “source of heat and light,”17—a greater act than the sum of its parts. At this, my art school brain went into overdrive. Their John Williams-like sculptural remix was sublimely political.

Immediately after returning from Seattle, Marc and I got involved in developing L.A.’s IMC, which opened in 2000 at the time of the Democratic National Convention. Soon thereafter we conceived of a publication that could sit somewhere between the grassroots publishing platform of Indymedia.org and the hard-edged theory of October. The first issue of the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest came out in June 2002. It was designed by Marc, with the help of my former classmate, and now wife, Kimberly Varella. Several of its articles were authored by our classmates at CalArts.18Over the years that followed, the Journal grew exponentially. Our print runs sold out. We were carried on newsstands and in shops in several continents. We printed early articles by activists, artists, authors, and thinkers whose work came to prominence that decade. The Journal arrived at a moment when many people noticed the inadequacy of old attitudes and theories to address the mounting problems of the neoliberal world order. People who were looking for ideas which connected them to a grounded collective and productive praxis found it in the Journal of Aesthetics And Protest. Marc and I emailed and met with Steven Lavine, who was then the president of CalArts. We didn’t know if he wanted to give us money, or plumb us for ideas, but we obliged him—he’d been our president after all.

Robby Herbst, Counter Culture Dialectics, drawing reproduced for article of the same name in issue #2 of the Journal Of Aesthetics and Protest, August 2003, pen on paper, 18 x 24 inches. Image courtesy of Robby Herbst.

When CalArts launched its MA program in Aesthetics and Politics in 2007, I barely noticed it. That was a very busy period for the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest. We were producing two book projects,19curating and supporting a museum exhibition of protest crafts called Street Signs and Solar Ovens, and conceptualizing a project for the 2008 California Biennial that consisted of an installation as well as an oversized issue of the Journal. For the issue I organized a study of creative protest projects initiated in relationship to the idiotic wars spilling out after 9/11. People always identified the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest with CalArts; I imagine that our approach, aiming to blur disciplinary boundaries, was on brand. When folks assumed we were involved with the new Aesthetics and Politics program, I wasn’t surprised, but we were not involved. I can’t help but wonder, in retrospect, how much our project influenced the decision of the Institute to launch their similarly named program. I stopped working on the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest in 2010. My twin brother still publishes it from Germany, where he moved later that same year.

Michael Asher died in 2012. Looking at the Art Program’s course offerings for Fall 2022, Gaines is still leading “Content and Form.” Thumbing through the other classes offered, I can imagine they’ve expanded the breadth of culture for which a CalArts education prepares its students to participate in; there are courses called “The Practice of Black Cultures,” “Art as Resistance,” and “Welcome to Migranthood!” There are also classes, like “Finite and Infinite Games,” that appear to locate contemporary art through non-art routes and histories. If I were at CalArts today, I’d enroll in the courses offered by the Aesthetics and Politics Program. The course description for “Contemporary Political Thought” states that it centers Herbert Marcuse and the “past-that-could-have-been,” and that it “mines the radical politics of the present for theoretical concepts that unsettle, erupt, and transgress.”

Making other art worlds possible was a preoccupation of several of my CalArts classmates. Alice Könitz constructs and exhibits idiosyncratic sculptural kiosks which generously become home for other artists’ works. These kiosks share a para-institutional title as iterations of the Los Angeles Museum of Art (LAMOA).20Mark Allen led Machine Project for fifteen years from a storefront in Echo Park. With Machine Project he framed a seemingly endless run of art and non-art practices, from carjacking to bull riding, as worthwhile and collective cultural experiences.21With the para-institution of the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, my brother and I, with the pivotal help of others including Cara Baldwin, Ben Benjamin, Ryan Griffis, Lize Mogel, Christina Ulke, Kimbelry Varella, set about to make a “weirdo think tank” and helped write into being what some refer to as social practice art.22From the end of the 20th century at CalArts and into the beginning of the 21st, we hoped to make a publication that magnified the autonomous, global justice, and anti-war movements as well as collapse the space between hard-left social action and cultural work. That this could be accepted today within the art world is not something I could have imagined from 1997.

Alice Könitz, LAMOA presents: Sonia Leimer, WOW! 2014 Los Angeles Museum of Art, Eagle Rock, CA. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer

The journal we created strategically took a visual studies approach to art and theory. We wanted to consider manifestations of visual art, protest, theory, and histories alongside the cultures that produced them, with no hierarchy of value placed between, say, a wig worn at a peace march, a sculptural invocation of organic farming, or a building occupation. We were interested in this all-things-at-once-ness for many reasons, including an avant-garde inclination towards an integration of art and life. With JOAAP I didn’t spend time worrying about the aestheticization of politics in the way that Walter Benjamin might, because my frame of reference was explicitly countercultural. It was not the broad political culture of American politics—Democrats, Republicans, and their elections. In seeking a merger between art and politics in the way that I did at, and after, CalArts, I was hoping to underline my understanding of the place for a visual artist in a movement. Rather than functioning as a figure on the bleachers providing side comments as I felt Asher did, or as a sign painter along the roadside offering graphics to be embraced by the mob, I was hoping to see a politicized culture that would embrace a boundlessness of creativity, a playfulness of mind, and an ethics of collective liberation.23

I recognize that this collective notion of production contradicts market forces which frame achievement for an artist working within the entrepreneurial model today. Also, this ethic of collective care is clouded by the ugly aestheticization of politics, which drives the broader American political discourse now. I know that, like the video stores and checked polyester pants which populated my 1990s, these market and fascist trends ideally will fade.

In my final month at CalArts, I tried writing something like a contemporary political aesthetic philosophy. Two years later, I reworked that essay for the first issue of JOAAP and called it “My Friends Are the Universe.”24Discussing an eclectic and international range of voices and actions, the essay aimed to catalog a conscientious orchestration of linguistic and physical ruptures in the normative functioning of totalitarian, corporate, governmental capitalism driven by an emerging “Global Justice Movement.” Objectives and tools always change, yet elsewhere people always conspire to make other worlds, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Robby Herbst (top image, in glasses) with Kimberly Varella, circa late 1990s. Photo: Mark Allen